Timber is one of nature’s most versatile and enduring materials, offering numerous applications unmatched by any other construction substance. From structural beams and posts to decorative wall cladding, ceiling linings, furniture, joinery, and expansive decking, timber’s indoor and outdoor possibilities are endless. Beyond its structural strength, timber transforms living spaces with its warmth, texture, and depth, creating a natural sensory connection that manufactured materials cannot replicate.

Australian timbers, sourced from the world’s finest and best-managed forests, are prized for their striking colours, grain patterns, and durability. They can withstand harsh climates and function as highly effective acoustic buffers, subtly absorbing and diffusing sound to create environments that feel alive rather than sterile.

Unsurprisingly, Australia’s high-quality native timbers have been sought after for many of the nation’s most iconic buildings. Yet, as this story will reveal, the very leaders who once celebrated the beauty and strength of our natural timbers would later turn their backs on them, sacrificing common sense and sustainable tradition in the rush for political expediency.

On a cool May morning in 1988, the new Parliament House in Canberra opened its doors with great fanfare. It was meant to symbolise a maturing Australia confident enough to showcase its national character through architecture, art, and materials sourced from diverse landscapes. Yet behind the ceremony, another story was unfolding, one thick with irony and hypocrisy.

The building designed to house Australia’s democracy was lavishly adorned with rare, highly prized rainforest timbers sourced from the rainforests of New South Wales and Queensland. Even as the chisels shaped these precious woods into ornate panels, flooring, and fittings for politicians’ offices, the same political class was working to permanently halt rainforest logging.

While the public marvelled at the grandeur, few understood that the bitter irony of the Parliament luxuriating in rainforest splendour would soon cast judgment on the foresters who had made such beauty possible. The professional land managers had long fought to sustain these forests against wartime and post-war political expediency.

A house built on national pride and rainforest timber

Plans for a new Parliament House had been seriously considered since the 1970s as Australia outgrew the “temporary” Old Parliament House, which opened in 1927. The new building, rising from Capital Hill, was designed to be both functional and symbolic. Construction began in 1981, and the official opening coincided with Australia’s bicentenary celebrations.

Architects Mitchell/Giurgola & Thorp envisioned a building that celebrates Australia’s landscape and natural materials. It was meant to be an architectural statement of national pride, with Australian timbers playing a starring role. Consequently, the construction of Parliament House created an intense demand for rare and difficult-to-source Australian rainforest timbers, which are highly prized for the features revered by the building’s architects.

No expense was spared in sourcing the finest materials. Rainforest timbers were handpicked for their beauty, durability, and prestige, particularly from northern New South Wales and even more so from Queensland’s lush tropical forests.

One celebrated example lays bare the irony. A sawmiller from Kyogle, Evan Williams, spent years setting aside an extraordinary collection of over 70 rare and unusual rainforest species that passed through his mill. They are timbers that would have otherwise been sawn into fruit boxes or packing crates. Instead, he air-dried them, believing they were destined for something more worthy, such as fine furniture, heirloom craftsmanship, or something of national significance.

He was right. When the designers of Parliament House discovered Evan’s trove, they eagerly snapped it up. His collection became the raw material for the 100 benches that now grace the building, each a mosaic of different rainforest species, finely cut into narrow strips and polished to perfection.

Yet here lies the irony. These exquisite benches, fashioned from the very forests politicians would soon lock away forever, are now largely hidden from public view. They are tucked away in exclusive chambers off-limits to the casual punter and banned from cameras. They have become the private playthings of a political elite who routinely denounce the practices that made them possible. And so, day after day, they sit — quite literally — on the legacy of the foresters they helped vilify.

If only timber had a voice, as those benches might scream of betrayal!

However, the Parliament House Construction Authority (PHCA) concealed plans to utilise rainforest timbers from the public. Their intentions only became known after the Wilderness Society obtained documents through a Freedom of Information Act request. The PHCA justified the use of rainforest timber by stating that it came from “areas already logged.”

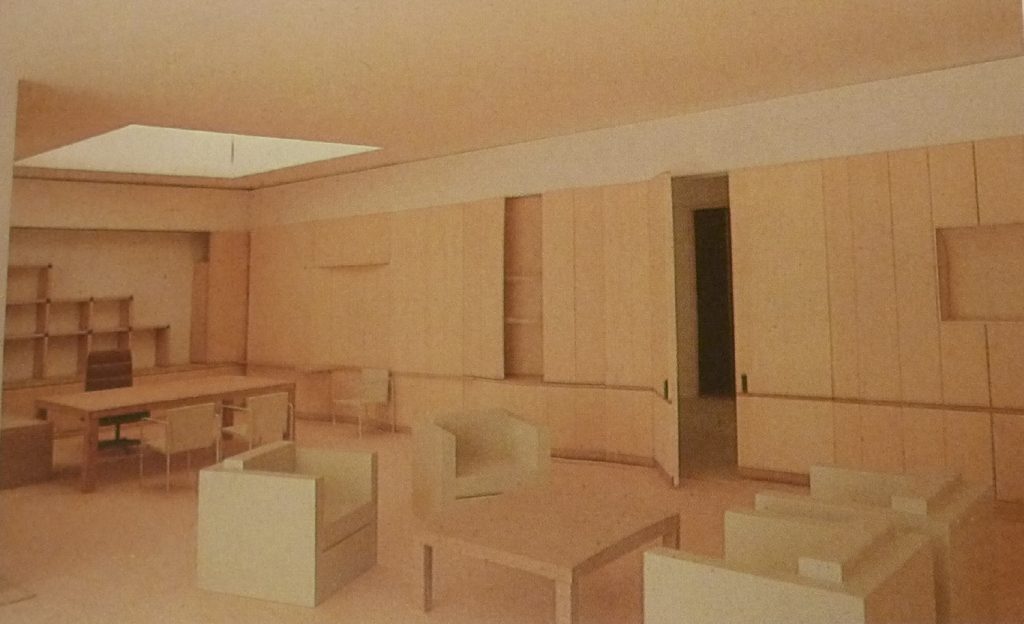

This was unsurprising given the political class’s double standards in Canberra. At the time their masters urged the Queensland Government not to log the Daintree rainforests, the PHCA planned to use rainforest timbers unique to the Wet Tropics, such as blush tulip oak (Argyrodendron actinophyllum), Queensland maple (Flindersia brayleyana), and the rare Queensland walnut (Endiandra palmerstonii), to create luxurious desks, chairs, and cabinets for their masters and to panel their office walls.

Even the prized celery-top pine (Phyllocladus aspleniifolius), myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii) and huon pine (Lagarostrobos franklinii) from Tasmania were targeted.

The Prime Minister’s suite drips with irony. Often described as a fabulous office, it is lavishly panelled in huon pine, a rare and slow-growing timber that can take over a thousand years to mature. The suite was designed by Tasmanian wood crafter Kevin Perkins, and the wood did not come from trees drowned in hydroelectric dams on the coast but from productive forests in the Huon Valley and Picton River. Chief architect Romaldo Giurgola travelled to Perkins’ studio in Tasmania, and together, they visited the forests that would supply the huon pine, not only for the panelling but also for special furniture and the door veneers throughout the four rooms of the Prime Minister’s suite.

This space of power and privilege is cocooned in one of Australia’s most valued natural resources. Perkins also crafted cabinets for the office from deep red myrtle sourced from Tasmanian rainforests. Red myrtle is highly valued due to its colour, fiddleback grain, raindrop and quilting patterns.

Yet, while the nation’s leader meets foreign dignitaries and makes grand pronouncements beneath that gleaming veneer, entire timber towns that once harvested such materials with skill and care have been left to decay. The mills have closed, the workers have moved on, and the forests — once carefully managed — are now locked away, sitting silently under benign neglect.

The irony lies not only in the fact that the room is lined with huon pine but also in the way those who sit inside now speak as if its very presence is a relic of wrongdoing. In truth, it is a monument to what was once a proud and sustainable national endeavour.

Many other rainforest species were sourced. Silky oak (Grevillea robusta) was used for wall panelling, its golden-flecked grain offering warmth unmatched by native and plantation species. Coachwood (Ceratopetalum apetalum) was prized for fine-grained cabinetry and joinery. Rose mahogany (Dysoxylum fraserianum) was utilised in high-traffic areas that require beauty and strength. Red cedar (Toona ciliata), that “prince of timbers, was once so valued that it sparked the cedar-getter economy in the 19th century. White beech (Gmelina leichhardtii) was selected for its pale, silky texture, which is ideal for flooring and wall treatments. The foyer also boasts white birch or crabapple (Schizomeria ovata) walls.

The Cabinet anti-room, its ceiling, and the main foyer feature marquetry panels with a coachwood background, bordered by jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata). Some panels utilise rare rainforest timbers, including Queensland walnut and Tasmania’s black-heart sassafras (Doryphora moschatum).

The Members’ Hall at the centre of the Parliament House complex is distinguished by its spectacular use of timber, particularly brush box flooring. However, the ceiling and many other large public spaces in Parliament House feature solid slats of silver ash (Flindersia bourjotiana), a rare rainforest species from Queensland, mounted a few centimetres apart to help absorb sound and reduce the echoing effect in the hall.

These timbers, sourced through carefully managed forestry operations, grace Parliament’s most prestigious offices, committee rooms, and public spaces. They are a silent tribute to Australia’s natural wealth and the generations of foresters who worked tirelessly to ensure their harvest was sustainable.

At no stage did the politicians question whether using rainforest timbers was appropriate. On the contrary, official publications celebrate the new building, boasting of the native species displayed within. Sustainability was assumed, not doubted.

Hypocrisy unfolds through the rainforest logging bans

Yet, even as these timbers were fitted into the parliamentary interiors, a political storm was gathering. In the late 1970s, environmental activism transformed rainforest logging into a national flashpoint.

Many preservationists claimed that timber harvesting in rainforests was not sustainable. While there are many examples from other countries where indiscriminate logging has occurred, often preceding clearing for agriculture, timber harvesting in New South Wales and Queensland’s rainforests was closely supervised and followed conservative silvicultural practices to ensure sustainability.

That mattered little when emotional arguments took centre stage. The first major battle occurred at Terania Creek in the Nightcap Range of northern New South Wales.

In the late 1970s, the NSW Forestry Commission planned selective logging operations in wet sclerophyll forests. The controversy was fuelled by the media mislabelling it as a rainforest issue. Activists, driven by an ideological belief that any logging was evil, organised Australia’s first “forest blockade” at Terania Creek. Protests escalated, often overlooking the fact that the proposed operations involved carefully controlled, selective harvesting.

Political pressure became unbearable. In 1982, the New South Wales government banned all rainforest logging in northern New South Wales without proper consultation with its forestry experts, following an exhaustive inquiry that favoured the forester’s management.

As I detailed in my series of blog posts on the Terania Creek protests, here, here and here, the politicians betrayed the foresters who had ignored their warnings during the post-war housing boom. Instead of being applauded for preserving sustainable rainforest practices, they were painted as villains, while activists and politicians basked in public adulation.

The Wet Tropics World Heritage listing

The Terania Creek conflict set the stage for an even larger showdown in Queensland. Throughout the 1980s, under Prime Minister Bob Hawke, the federal government campaigned for the World Heritage listing of the Wet Tropics of Queensland – a massive expanse of tropical rainforest stretching along the coastal ranges. In December 1987, Senator Graham Richardson nominated the Wet Tropics Rainforests for World Heritage listing. The following month, he introduced regulations banning commercial logging in the nominated area, even though the nominated area had yet to be considered by the World Heritage Committee. He used an external treaty, and the supporting World Heritage Properties Conservation Act, 1983, as its justification and legal basis for his actions.

By that time, logging activity in these forests had already declined, as operations shifted from virgin stands to regrowth and previously harvested areas. The sawmilling industry – especially those reliant on rainforest brushwood species – had adapted to lower yields per hectare and the need to work with smaller sizes and less commercially desirable species. Rather than resisting these changes, the industry embraced them, maintaining profitability through innovation and resilience.

As in New South Wales, decades of politically driven overcutting, particularly during wartime and the post-war building boom, had taken its toll. This was not the fault of foresters, who had long warned of the risks. In fact, by the early 1980s, foresters were actively reducing the allowable cut and steering the industry toward long-term sustainability.

Opponents of logging pointed to the declining harvest volumes of the 1980s as evidence that the industry was unsustainable. But this was a misinterpretation. Much of the volume reduction was due to the shrinking available land base, as large tracts were converted to agriculture or absorbed into national parks. More importantly, the allowable cut in those years had never been based on ecological yield analysis, but on political expediency, which was a long-standing grievance of professional foresters.

By the mid-1980s, foresters had achieved meaningful reforms. They progressively lowered the allowable cut toward levels that could be biologically and economically sustained. But just as these reforms began to take hold, the rug was pulled out from under them.

The Queensland Government under Joh Bjelke-Petersen fiercely resisted Commonwealth interference, defending sustainable logging practices and regional jobs. The Federal Government attempted to block the Queensland government’s High Court action challenging the legality of its actions through legislative amendments contained in the Federal Legislative Amendments Act, 1988.

However, the political momentum was unstoppable. In December 1988, the same year Parliament House opened its rainforest-adorned doors, the Wet Tropics were inscribed on the World Heritage List.

Hundreds of logging jobs were lost, and regional economies that had depended on careful, selective timber harvesting collapsed. Once again, politicians who had luxuriated in rainforest timber surroundings now piously declared that no logging should occur, not even under sustainable management regimes that had been painfully implemented after previous governments sanctioned the wholesale overcutting of forests to meet intense demands during the war and afterwards.

The federal government’s decision was hailed as a triumph for science and preservation, but the reality was more complex. The World Heritage Commission conducted no independent scientific assessment of logging impacts or forest health. Instead, it relied almost entirely on emotive claims from environmental activists, dismissing forest inventory data, yield modelling, and ecological monitoring by Queensland’s forest scientists.

Yet detailed modelling had already demonstrated that selective logging in these rainforests could be sustained indefinitely, delivering a modest, perpetual yield while maintaining species diversity and forest structure. Their simulation studies, grounded in rigorous inventory data from the 1980s and advanced growth models, showed that well-regulated logging posed no threat to biodiversity.

But politics trumped science. In the rush to placate green activists based in the cities far away and score international accolades, the Commonwealth extinguished a sustainable industry and discredited the very foresters who understood the forest best.

The hypocrisy was breathtaking.

Rainforest timbers in service of the nation

Australia’s use of rainforest timbers was neither reckless nor new. In fact, during the greatest national crises, these timbers had been critical to Australia’s survival.

During World War II, rainforest species were harvested extensively. Coachwood and Queensland maple were prized for rifle butts because their shock absorbing qualities made them ideal. Silky oak and crows ash (Flindersia australis) were used to construct de Havilland Mosquito bombers, where lightweight strength was essential. Red cedar created lightweight, durable transport cases and cabinetry for military use.

These urgent wartime demands resulted in heavier-than-normal logging, often conducted in conditions that disregarded sustainable practices, something foresters bitterly opposed but were powerless to prevent under wartime conditions.

Following the war, the housing construction boom once again placed enormous pressure on Australia’s native forests. Expediency trumped sustainability. Politicians, desperate to house returning servicemen and their families, and boost the country’s economy, ignored foresters’ warnings about overcutting and future shortages.

Foresters found themselves in an untenable situation attempting to implement sustainable harvest practices while required to meet unattainable extraction targets. When the forests inevitably suffered long after the war ended, the blame fell on the foresters, not the politicians who set the quotas.

The Sydney Opera House and white birch

Even Australia’s most iconic building, the Sydney Opera House, owes a great deal to the nation’s forests. Apart from being widely recognised as one of the greatest buildings of the 20th century, it has become Australia’s premier tourist destination and its most recognised symbol.

Much of the building’s interior features white birch timber, predominantly from the Hastings Valley in New South Wales. White birch was selected for its uniform, pale finish, resilience and workability — qualities that are impossible to match with plantation alternatives.

At that time, no one protested the use of rainforest timbers. The Opera House was — and remains — a national icon, celebrated without a murmur regarding the forests that supplied its materials, even after the recently upgraded interior used similar timbers.

Australia’s foresters: the forgotten professionals

Australia has been uniquely blessed with professional foresters trained to world-leading standards. From the early 20th century, these men and women implemented sustainable silvicultural systems of selective logging, regeneration protocols, and ecological monitoring to ensure Australia’s forests could be used wisely without being destroyed.

Given the ecological complexity of rainforests, these systems were even more rigorous. Sustainable yield logging in rainforests represented a remarkable achievement of extracting a small fraction of the standing volume, promoting regeneration, and maintaining forest structure and biodiversity.

It was not the foresters who decimated forests during World War II and the post-war housing boom; political decisions were made under expedient pressure. Yet when the environmental zeitgeist shifted, it was not the politicians who were blamed for past excesses. It was the foresters who were left to defend themselves without support.

Meanwhile, politicians revelled in their rainforest timber offices in the new Parliament House, moralising about the need to “save” forests they had already plundered.

Australia could have continued to harvest rainforest timbers sustainably, offering the world an example of wise resource management that combines ecological integrity with human use. The foresters knew how, the forests were capable, and science supported them.

Instead, politicians pursuing green votes and international accolades cut down the profession, not the trees.

The new Parliament House, adorned with the ghostly remnants of beautiful rainforests, is a silent monument to that hypocrisy. Rich and beautiful timbers tell a story few Australians know. It is a story not of reckless destruction but of stewardship betrayed by political expediency.

Foresters were hung out to dry, vilified by activists, abandoned by governments, while the institutions that condemned them were built literally from the fruits of their labour.

Oh, the irony.

A tough read, to be honest. Thank you for reminding some and hopefully informing many.

A great peice thanks Robert. I would love to see an exercise where a building or even a small community has every timber product removed. People would suddenly realise how much we depend on timber products in all aspects of our lives.

A wonderful history sadly maligned.

Well said!

This should be required reading in schools, but they have become indoctrination institutes that do not allow for any critical thinking.

Thanks Robert. Another key issue was the zeal of foresters and forestry departments to dedicate huge areas of forest areas as state forests often against lands department and ag interests and this stopped huge areas of land from being cleared. It is rarely recognised.

An industry forsaken. My time with Qld Forestry came to an end in 1966 as I could see the noose tightening.

So much of the country is lacking good land management skills.

Silviculture was developed as a way of producing timber while keeping forests healthy and productive.

Politicians pushed for systems that suited the “optics”, not the forests, so now we have forests that are both unhealthy and unproductive.

Agree with Andrew above. . .a tough read, but beautifully written, and warmly received recognition, Rob, thank you again.

Alas, I don’t think the elite politicians and agenda-driven bureaucrats have any moral fibre, and their devilish skins protect them from casting a reflection when we hold up a mirror in an attempt to show their hypocrisy.

Well written, Rob.

I reckon you are the only person with the breadth of knowledge (expertise) and the intellectual strength (willingness to “call a spade a spade”) that all Australians need to respect.

Thank you, Allan — that’s very generous. I’m far from alone, though. Many foresters before me, and many still active today, have been fighting hard to defend our noble profession. Sadly, activists and some academics often take the easy route, offering a simplistic yet uninformed narrative that overlooks the complexity of forest management.

This writing is the release of years of pent-up frustration I had to keep bottled up during my career. There are so many hidden and complex aspects of our work that deserve to be explained, so the public can see forestry for what it truly is.

It’s disappointing that even our professional body, which was created to represent foresters, seems to have lost its way and no longer provides the advocacy we need. That makes it all the more critical for those of us who can to speak up.

As the wife of a forester who lived through those years, this is a splendid article. Submit to “The Australian” please, so more people will read it. All those who had a part in the destruction of the forestry profession should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves.

Amazing, is it not. When one talks about what happened, eyes glaze over. Most newspapers for some reason seem to lack the courage to publish anything which goes against the narrative.

Thank you for the thorough article. It is still going on … have a look at the timber interior fit out in the new Australian Embassy in Washington. Beautiful forest timbers from forests that are still being locked up and converted to national parks. Oh the irony!

Thanks, Gaela, I will write a Facebook follow-up post about that, highlighting the move to lock up a lot of the coastal blackbutt for the Great Koala National Park.

Thanks Rob for articulating the truth so well.

Rob, as one of the other commenters has recommended, please submit it to the Australian. There are plenty of other examples where our profession has been maligned by ratbag greenies who have no morals or ethics.

You have summed up the hypocrisy beautifully.

FYI

Posted at https://joannenova.com.au/2025/09/saturday-126/#comment-2867881

Very interesting piece, as a forester coming in to the industry in the mid 1990’s rainforest operations were a thing of history but I worked with some who managed rainforest operations in the past, very committed people. I marvelled at the stories of foresters taking a chip out of trees and identifying rainforest species by the smell of the wood. They also talked of and pointed to the areas of rainforest logged under their watch to fit out Parliament House – the irony was not lost on them.

I was proud to call myself a forester when I worked as one back in the day. I am still proud to say I am.

I undertook one of the most well rounded and thorough degrees that taught all aspects of managing a forest for natural resource production. Not just timber, but air, water, tourism, biodiversity and human soul restoration.

Australian silvicultural trials and logging practices proved that the forests could regenerate and increase their biodiversity. A fact now proven by the way we now know it was manipulated over thousands of years by the original foresters.

A wonderful insight into how we have now had our forests hidden behind the facade of ignorant, misplaced and mistaken ideology.

When the Terania Creek activists called a public meeting in The Channon Hall they invited the young Assistant Forester of Murwillumbah District to speak. He prefaced his address by saying the meeting was being held in the wrong place.

The Channon Hall was a timber building, the chairs/stools they were sitting on were all wooden, the blackboard they were writing on was wooden, and all the information was printed on paper which had a forest origin.

The real reason, in my opinion, for the Terania Creek demonstration was to prevent log trucks sharing the Shire Road. How do you stop the log trucks? You stop the forest harvesting! They produced a TV ad which showed 20 seconds of the serene scene of mummy taking her children to school then 2 seconds of roaring log truck with this sequence repeated several times.

The forest they were “saving” had been harvested before and had regenerated.

I forgot to note that The Channon settlement and Hall were all on cleared ground that had been part of “The Big Scrub” as had the land where most of the protesters were living.

Hi Robert, Thanks for a very well researched and written article.

You have highlighted the hypocrisy of politicians, but they really just reflect the broader community that votes them in. There is community-wide hypocrisy in relation to all environmental issues given that we enjoy a relatively comfortable standard of living due to resource usage, while simultaneously wanting to end resource use to ‘save’ the environment. At the heart of this is voter apathy and ignorance that is implicit in an easy willingness to believe often outrageous misrepresentations of environmental impacts promulgated through a mainstream media that has long ago lost its objectivity in relation to such issues.

You mention disunity amongst the forestry profession in relation to defending commercial native forestry, but I would argue that we are now more unified on this issue than ever with Forestry Australia devoting more effort to advocacy than it ever has. Unfortunately (and perhaps predictably), it has taken the politically-forced end of commercial native forestry in Victoria and WA to magnify the threat and cement this unity when the fight to maintain sensible forest management is now at least half over.

Unfortunately, when the fight was still in the balance 15 – 20 years ago, there was definite disunity amongst foresters that constrained efforts to challenge anti-forestry activism. I can still remember a senior IFA member’s view that defending commercial native forestry was the timber industry’s battle, with the IFA urged to stay out of it or risk losing its status as an impartial scientific body to become known as a pro-logging lobby group! So, the forestry profession which had developed the silvicultural techniques, assessed and planned log volume quotas, and regulated harvesting practices largely sat it out.

The timber industry has by and large done a pretty good job in defending forestry and their part in it, but the label of economic self-interest has been too easily used to undermine the integrity of their message. But the power of a collective 1000+ strong scientific voice for forestry was largely missing, and arguably this was not lost on the media who assumed that it justified their view that native forestry is indefensible.

To effectively defend multiple-use forest management, foresters would have to have adopted a zero tolerance approach to activist/media misinformation 25-30 years ago. Unfortunately, most foresters with the insights and capability to urgently challenge and correct misinformation worked in government agencies and were prevented from public commentary by public service employment constraints. That left the IFA to speak on behalf of the forestry profession, but (as above) they were lukewarm about doing so, and arguably lacked the financial resources to fund what would have been a full time job. So …… here we are today where activist misinformation has over decades shaped a societal ‘conventional wisdom’ that commercial native forestry must cease.

True words.

I sit here tonight after the latest example of collective ignorance and stupidity (Great Koala National Park) and wonder if I should go on in this career or retrain.

I’ve had a good career – improved the profession with my contributions. From starting out the late 90’s in farm forestry traineeship in Dorrigo, NSW giving me the tree bug, uni in Lismore, 10 years in Forestry Tasmania, firstly in research (CWD), then in resource modelling where I knew that harvesting was sustainable as it was my model!

I had PTSD from the forest wars that ended in the Tasmanian first agreement. I moved to the Sunshine Coast and measured and modelled the fantastic plantation resource for 8 years and now modelling the sustainable yield in NSW for Forestry Corporation for the last 3 years. I also know it’s sustainable as it’s my model!! (built off a lifetime of dedicated work by Tim Parkes)

It’s sad to say goodbye, but perhaps I should just retrain as a doctor. It will be less complex but at least I’ll be respected, and paid well. Heartbreaking.

PS Actually, like most foresters, I think I’m still too passionate to give up! 😁