“The greens are like goldfish. No matter how much you feed them, they always want more.”

The Terania Creek forest blockade

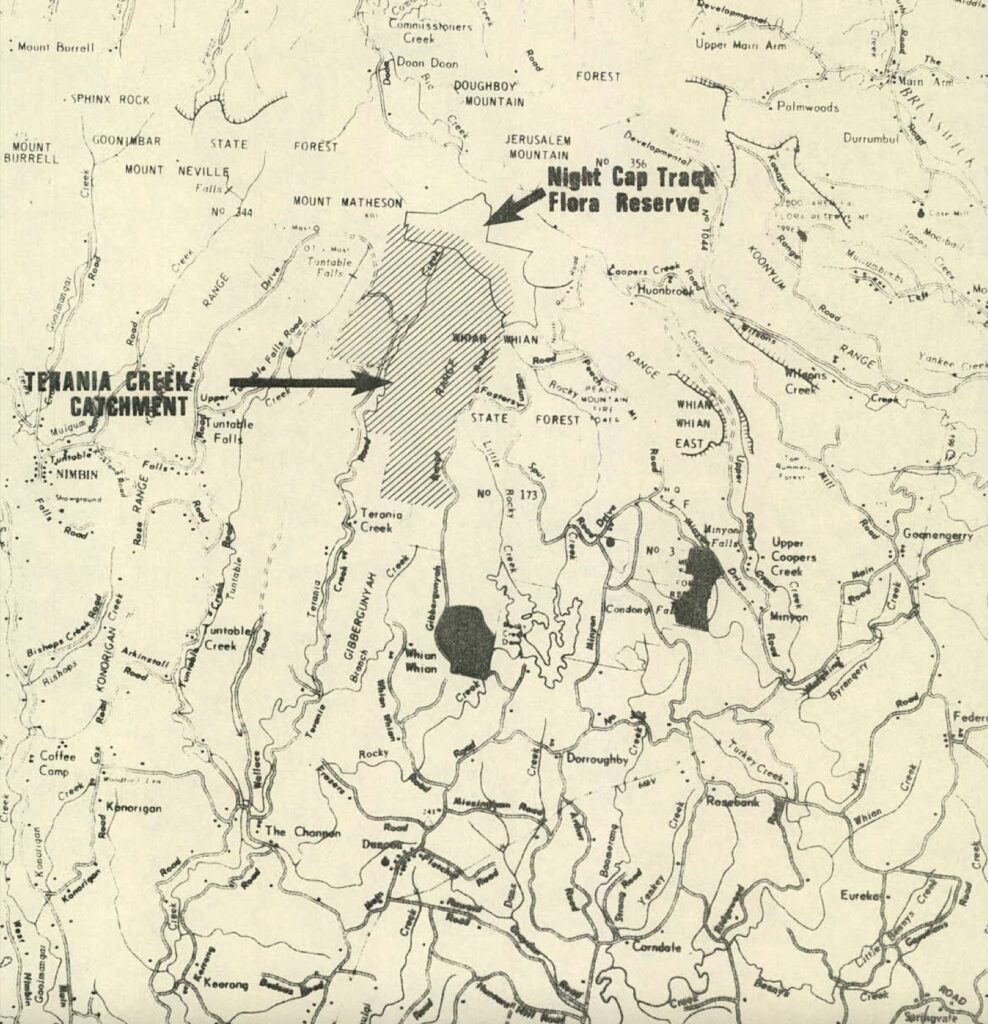

Interest in Whian Whian and Goonimbar State Forests by locals was first raised in a letter in July 1974 to the Forestry Commission of New South Wales (FCNSW) about their plans to log at the head of Terania Creek. It was followed by a meeting between two new settlers and the district forester at Murwillumbah.

The following year, FCNSW Murwillumbah assistant district forester Bob Fredericks addressed The Channon locals about plans to log near the Nightcap Range. Little did he know he inadvertently set off a chain of events culminating in the infamous forest blockades at Terania Creek four years later.

Among the 250 people at the meeting were Hugh Nicholson and his wife Nan, who bought a rundown farm adjoining the planned logging area in 1974 to develop a native plant nursery and farm goats. They were part of a new wave of settlers, attracted to the lush forests of the north coast valleys representing an environment they dreamed of while living in the bleak suburbs of the cities down south.

There were plenty of abandoned and marginal dairy farms in the foothills of the ranges where they could set up their idealistic commune lifestyles. The new residents quickly became involved in a series of local environmental campaigns. They caused a lot of social upheaval within the traditional local farming and timber communities. The newcomers had little or no farming skills and offered only unproductive values. What was more galling, a lot didn’t have to worry about working to earn money because they relied on social security payments.

The initial plans of FCNSW at Terania Creek were to selectively log in some rainforest stands and heavily log some brush box (Lophostemon confertus) forest, burn the residue and replant with flooded gum (Eucalyptus grandis).

(Left) Hugh and Nan Nicholson outside their property in the late 1970s.

After The Channon meeting, the Nicholson’s formed an organisation with their neighbours and fellow idealistic refugees from urban life called the Terania Native Forests Action Group (TNFAG). They argued that the Nightcap Range supported pristine ancient rainforests. The area was dedicated as a National Forest in 1937, but all that meant was it provided the opportunity to open the forest to settlement, not preserve it. That didn’t stop the need to find timber to supply the war effort, and it was heavily logged during that time.

This inconvenient truth mattered little to the overzealous TNFAG. Nor did the fact that there was a reserve associated with the Nightcap Track in the upper section of the Terania Creek basin. They rejected FCNSW compromise options, wrote more letters and made several representations at a local level to stop any logging going ahead. TNFAG called for an Environmental Impact Study claiming the FCNSW had acted contrary to the State Pollution Control Commission’s policy by not preparing one.

The small group of new residents that objected to planned logging in their backyard were at it for four long years. They developed a sense of self-righteous resentment of foresters, loggers and sawmillers, who they believed were paid to commit immoral acts. Even though FCNSW, in good faith, agreed to scale back the planned logging area and not log any rainforest, TNFAG would only agree to no logging at all.

By the end of 1978, FCNSW had agreed to selectively harvest only the brush box stand in the ecotone adjoining the pure rainforest area covering 77 hectares, but TNFAG rejected this. In May 1979, the minister visited the logging area at the invitation of Lismore City Council and in company with representatives of TNFAG, timber interests and FCNSW. After compromising for nearly four years without any concession from TNFAG, the minister announced logging would proceed after a Cabinet meeting in Murwillumbah. Rain prevented any operations commencing until late winter. TNFAG decided they would hold a protest when logging operations started. They alerted the media just beforehand.

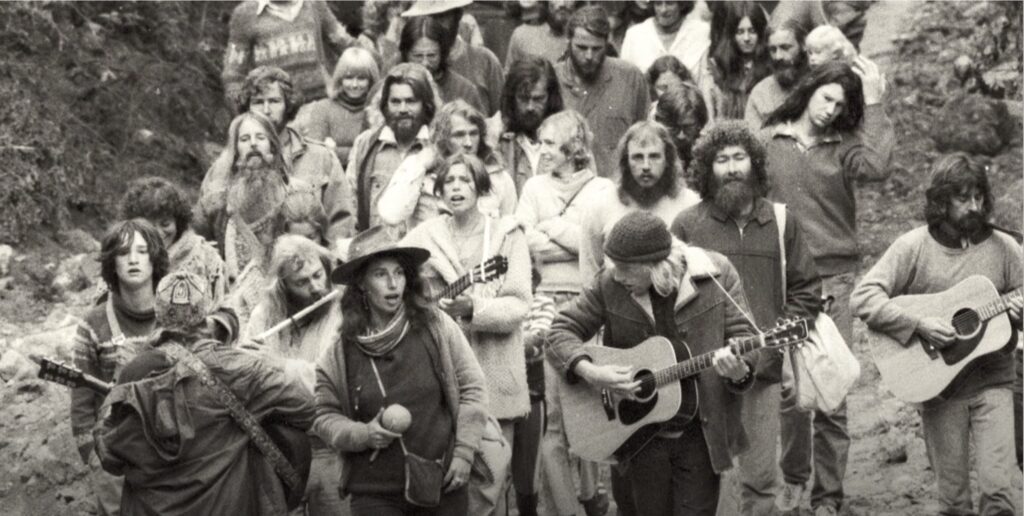

Protesters singing at Terania Creek. Photo David Kemp.

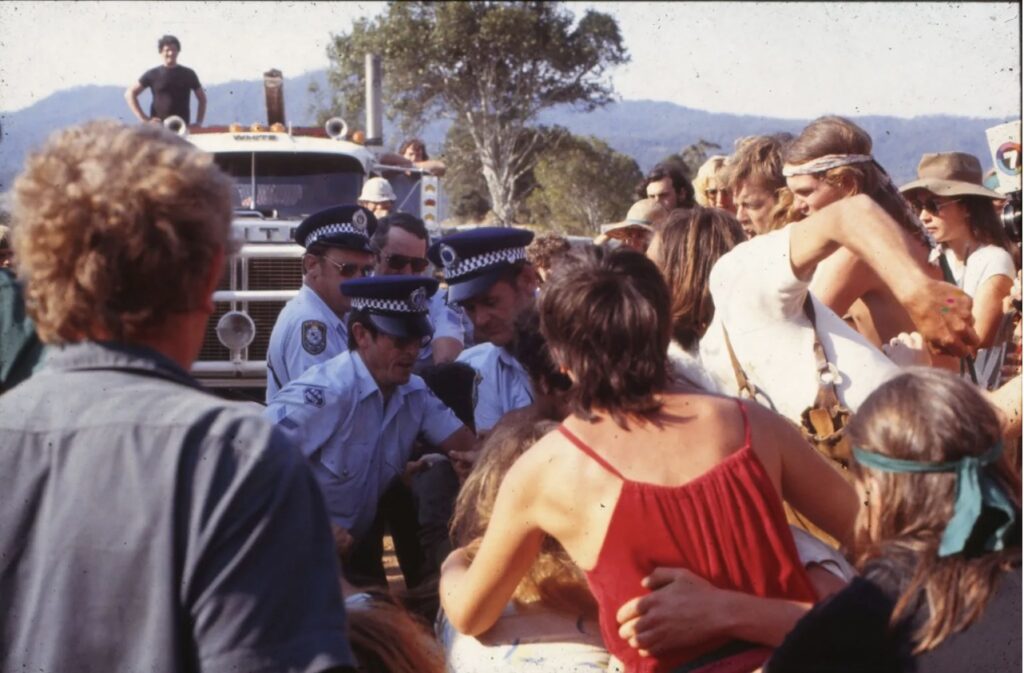

On a sunny winter morning on 16 August 1979, the Standard Sawmilling’s logging contractor had his bulldozer on a float destined for the logging compartment. After unloading on the main road, the machine cleared the overgrown logging track the next day. After that was completed, 200 well-organised people physically stopped the bulldozer from entering the logging compartment. They had travelled from the cities and camped at Nicholson’s property. They adorned the machinery with flowers, sang, and chanted to guitars, mandolins and flutes.

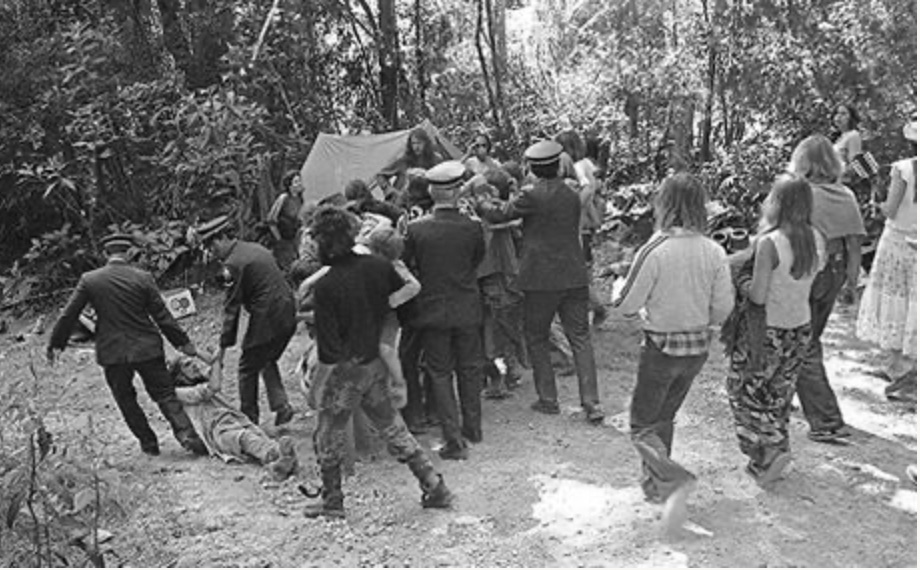

In response, and supported by the New South Wales (NSW) Cabinet, 120 police arrived soon after dawn the next day to assist the logging contractor to start operations and maintain law and order. When the logging crew began moving into the forest with the help of the police, everything suddenly changed. It was a physical confrontation that the local protesters claim they had not planned but still had the foresight to alert the media that something worthwhile was going to happen to attract their attention.

A wave of anger and resentment swept the crowd. People were dragged by police from the machinery and arrested. TNFAG members took advantage of this situation and fed stories and images to the media with such effect that Terania Creek became the most newsworthy event in the state for the next two weeks.

Suddenly, helicopters circled overhead. It was heaven for the city media, who loved the drama, the noise and the panic playing out in front of them. The fighting in the forest with the arrest of 100 people made excellent television footage. Once calm was restored by police, they began herding the throng of protesters from the forest, and even then, some reacted for the benefit of the television cameramen. TFNAG claimed the police exercise was:

“An absurd over-reaction. The cost to the taxpayer and the whole campaign against us is much greater than the costs of an environmental impact statement”.

It was lost on TFNAG that the action by the police wasn’t a campaign against them. Instead, it was a response to their campaign against a lawful practice sanctioned by the government at the time.

Various Sydney environment groups, including the Colong Committee (CC), quickly became interested. They changed their indifference to the bearded hippies and began cheering “those brave souls who were physically confronting the enemy”. They wrote to all members of parliament and provided supporting statements.

Protester Neil Pike dragged away from the protest site by police. Photo Darcy McFadden.

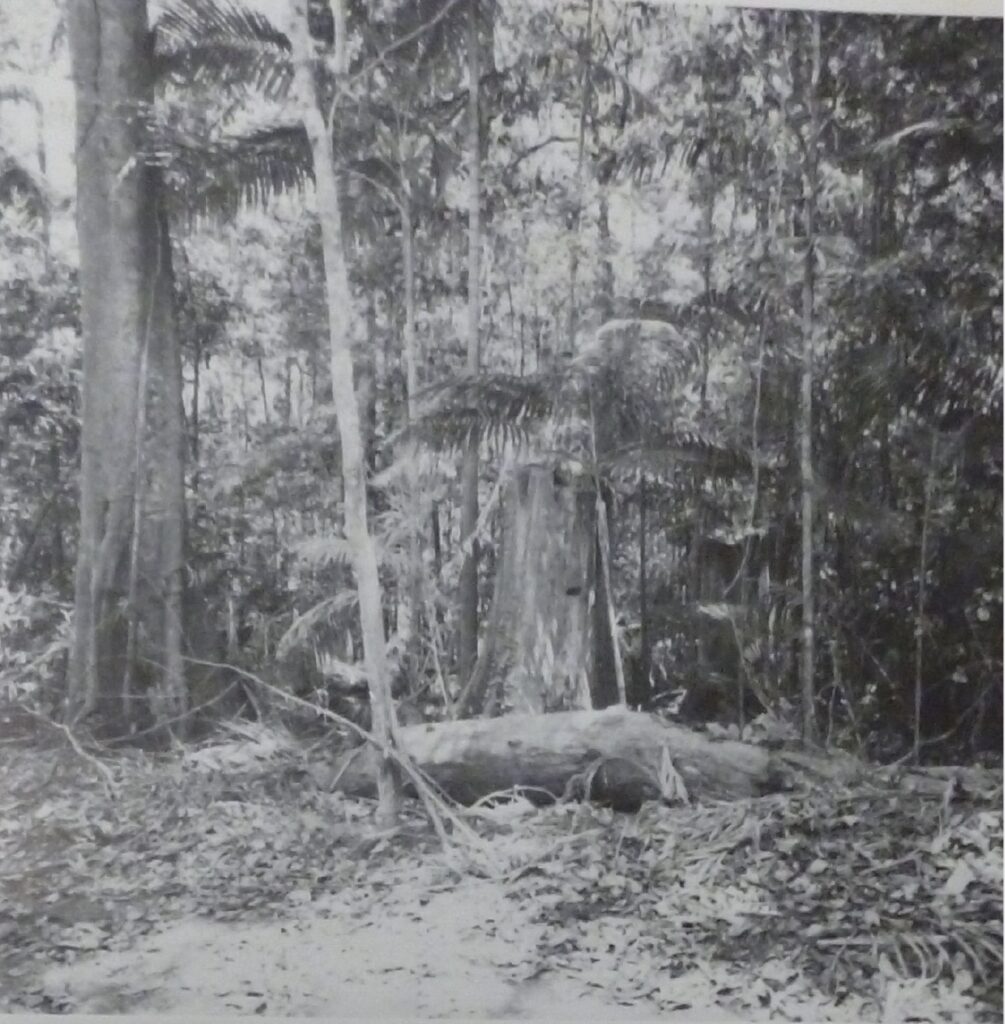

A day’s work turned into a week for the logging crew, but finally, they opened an old logging track after four years of negotiations and delays. Tall, weathered stumps from past logging operations stood as sentinels and surrounded the log landing area. The notches in the stumps signified a time when fallers were in the forest and used springboards to fall the trees with axes and drag them out by bullock teams – hardly a sign the area was the remnant from the Gondwanan period parroted by the activists and glossed over by the Sydney media.

Late in the day, a single protester, Peter Saulwick, foolishly tried to stop tree faller Ned Harvey while he was operating his chainsaw. Police quickly arrested him, and video footage taken by Paul Tait went national on television news and ABC Radio. As the police hauled him inside the police van, he yelled out, “you kneed me in the balls”, thus ensuring his testicles gained worldwide infamy.

Since when are eco-guerilla sabotage acts and personal threats non-violent?

What was not reported by the media, nor in the books celebrating the protesters as saviours of the forest, was what they did next. It wasn’t a peaceful protest by any means.

Threatening phone calls to sawmiller’s families started in earnest. The Production Manager at Standard Sawmilling, John Macgregor-Skinner, was one of the victims. At 1 am one morning, someone told him on the phone:

“We know where your kids are. We know where your kids go to school; they’re not going to come home tomorrow. We know where your wife is, and she’s going to get raped.”

His wife answered a call another day, and was warned down the line, “we’re going to burn your house”.

Helen Withey, the wife of the managing director of Standard Sawmilling, was also targeted. She received two nasty phone calls. Afterwards, she ensured the school wouldn’t let her kids out of the gate until she picked them up.

Innocent, hard-working families now found they had to have police protection as they feared for their children’s lives and themselves.

Margaret Henry, the wife of FCNSW Chief Commissioner Jack Henry, was moved to write a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald publicly raising the unassailable abuse those in the industry received trying to do their job:

“My husband belongs to a profession – forestry, which has undergone systematic and sustained denigration…silence is the only recourse for a forestry family”.

Meanwhile, Ned Harvey and his logging crew tried to log the Terania Creek coupe. With all the interruptions at their workplace, harvesting was slow. They now relied on 150 police to allow them to fall trees, do their job and sleep safely at their logging camp. During this time, they pondered their futures after a stressful first week of direct protests. They were losing money. But this was of little concern to the protesters and the media.

With CC’s involvement, suddenly, there was a formidable opposition which had the advantage of a sympathetic urban media that allowed them to combine dramatic imagery with their rhetorical claims. They managed to highlight messages of “raping” the forest, which the media gave extensive airplay in the form of the loss of species and disappearance of rainforests. There was even a global dimension to the protests with the non-rainforest logging compared to tropical rainforest destruction in Asia and the Amazon Basin.

The Australian Conservation Foundation sought donations through their Habitat magazine for a rainforest fund which was used to good effect to lobby members of the parliamentary Labor Party and leading unionists. They provided form letters to the readers of the various environmental newsletters and magazines to write to politicians. When they visited ministerial advisers or departmental bureaucrats, they referred to the minister by the first name to imply a level of familiarity which did not exist. Another deception was to take advantage of the minister’s lack of memory with details and use that to bypass bureaucrats and commence personal letters with the phrase “When we last met, I promised to send you…”

They selfishly attacked the forest industry and tried to portray the last remnant of rainforest would be logged, destroyed and eliminated. Their modus operandi at every protest was to save the last remaining patch of rainforest in that area. They gained attention by organising successful disruptive activities. Protesters operating as scouts, equipped with CB radios, hid on adjacent ridges, and trail bike riders patrolled the roads.

Apart from the deceptive propaganda used in pamphlets and media releases and the verbal threats mentioned earlier, there were several examples of violence. Egged on by the media, it was hardly surprising that extreme acts, such as deliberate and dangerous sabotage, became part of the struggle to stop the harvesting of trees by a subset of radical activists joining the protests.

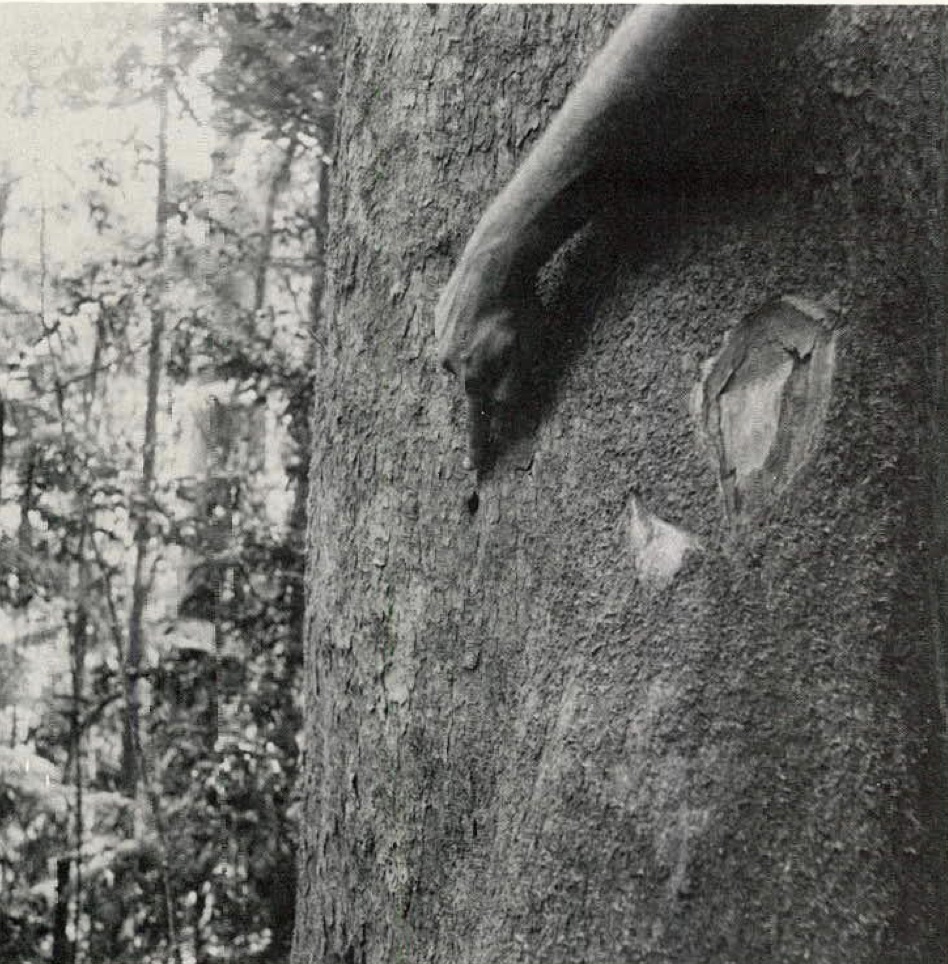

(Right) A brush box tree marked for felling was sabotaged by a steel spike driven into trunk, making it too dangerous to fall.

The media failed to report two young students, one named “Brett” by Byron Bay author Lester Byron in an article in Rolling Stone, who slipped into the forest one night and located two marked trees for felling. With the aid of spiked boots and a belt, each climbed up a tree and randomly inserted 12-inch nails. They spent five hours spiking 20 trees and another hour making deep cuts with a chainsaw in the felled trees awaiting removal. They knew that if trees with metal spikes found their way to the sawmill, they could kill or severely maim the saw-bench operators in the mill. In addition, a broken chain from a high-speed chainsaw could chop the operator in half.

The media also gave scant coverage of the damage to logging machinery or to the two police cars that had their wheels removed. They didn’t report the truck driver hit in the face just below the eye by a stone from a shangai. A few inches higher and his vision would have been lost.

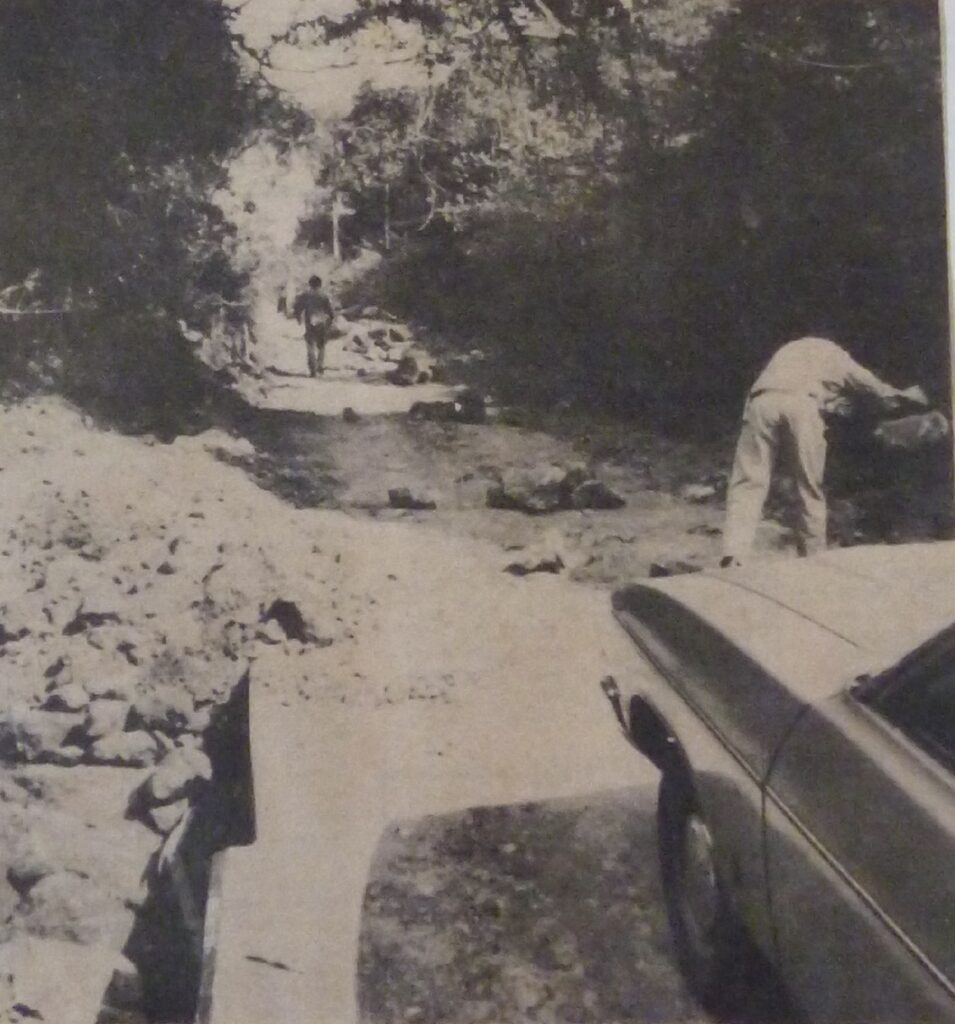

Nor did they report the abuse and invective hurled at members of the logging crews and FCNSW personnel. Nor did they report the 3-foot x 3-foot trenches across the main road where they hammered steel pipes into the ground, and to give it a sinister twist, barbed wire was placed below the spoil from the trenches, causing severe damage to the hands of FCNSW staff and police officers who tried to repair the damage. No one in the media reported these things because the activists told them they were carrying out a non-violent protest.

(Left) Removing rocks from the road.

Although, one reporter did quote Detective Sergeant Eric Strong from Lismore describe the protesters as a “bunch of clowns” after they covered a bulldozer in human faeces. Large rocks were also placed over the road to prevent trucks and cars from using the access road, again not reported.

Another act of sabotage was the deliberate arson attack on the Hurfords hardwood mill at South Lismore, which was burnt to the ground, even though they had little to do with harvesting in Terania Creek. The subsequent coronial inquiry found the fire was due to “causes or persons unknown”. There was evidence at the hearing that someone was seen running away from the fire. In addition, there were rumours in the local community that two people accessed the site swimming across the river.

Fireman hosing down soldering remains of Hurfords mill.

The leaders of the environmental groups were careful to try and distance themselves from these acts of destruction and sabotage. One example at Terania Creek was after a bulldozer’s battery lead was cut. Another incident not reported by the media. Protesters set guards to make sure there was no repeat performance. However, one prominent protester, Milo Dunphy, publicly admitted they had plans to carry out violent actions by admitting they had contingency plans to blow up a road during the previous Colong-Boyd Plateau protests.

Sadly, eco-guerilla tactics were not new at Terania Creek. It was a tactic first used in Australia at Bunbury in 1976. Then, in the early morning hours, two young men, masked and armed, held up the night watchman at the woodchip export terminal. They used almost 1,000 sticks of gelignite in three packages. Luckily only one package detonated, but it was enough to blow up the conveyor tower.

In October 1978, activists put acid into the fuel lines and abrasives into the machinery gearboxes at the Harris-Daishowa export plant at Eden in NSW. The following January, another bulldozer was damaged similarly, and a fire, started by arsonists, destroyed the big woodchip pile at the export terminal.

During 1979, protestors damaged eleven forest machines at various places on the north coast region by placing sand or gravel in their gearboxes or destroyed them by fire, at considerable cost to the owners, many of whom were private, small contractors.

These acts of industrial sabotage showed that the environmental movement had a large element of militancy and it was far from a non-violent civil disobedience movement that was practised during the Vietnam War demonstrations. It was no surprise when the Tasmanian Hydro Electric Commission (HEC), the scapegoat in the Franklin Dam issue of 1982, was subjected to acts of vandalism. Besides flooding its offices, protesters damaged HEC equipment on a remote helipad near the King River.

While only the Bunbury bombing could conclusively show environmentalism was the motivation for sabotage, the unusually high concentration of these acts, and their coincidence with sensitive and controversial environmental projects, strongly suggest that the other actions had the same motivation.

Ned Harvey had a close call while operating his chainsaw in the bush:

“Well, I’d got a brand new chain on, and I laid in and started to cut the tree. Well I got the belly in all right, and I went around to cut the back of it, and the next thing bang! … There were seven-inch spikes in the tree”.

These desperate and violent acts were never reported in the news, even though they made the protests successful. Google Terania Creek or read the plethora of books lauding environmental action. They will portray the blockade as the first time an environmental group used non-violent “direct-action strategies”. The hidden truth shows this as a fabrication – a myth maintained for over 40 years.

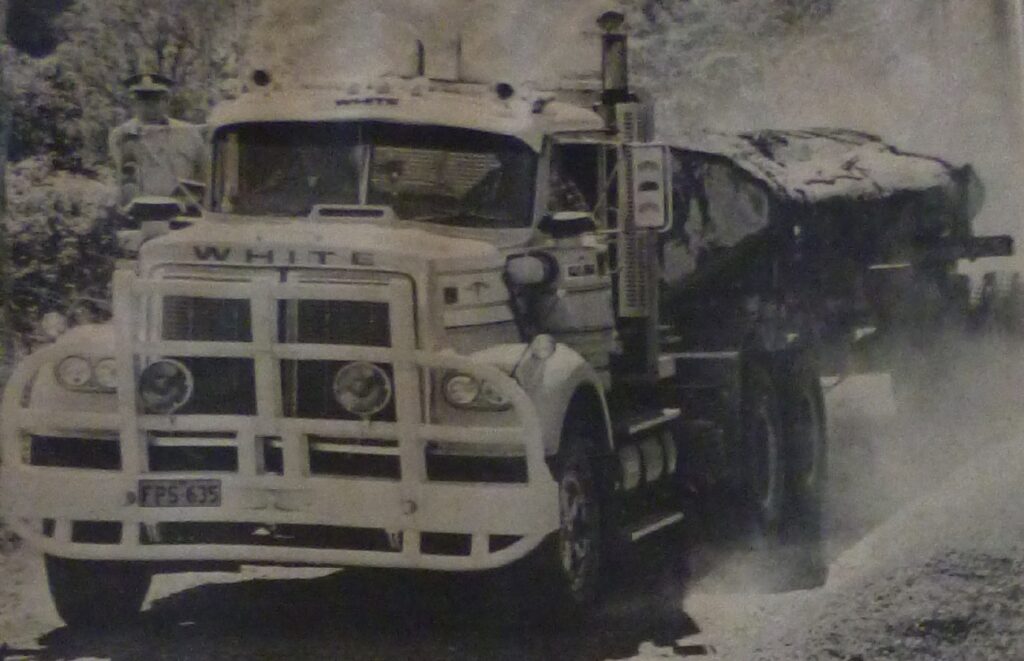

Meanwhile, it took two weeks to get the first truckload of logs out of the bush. On Wednesday, 29 August, three timber jinkers were at the log dump, ready to remove logs damaged by protesters. They required more than 70 police, riding “shotgun” on semi-trailers, for each convoy to leave the forest. This cost the state government and taxpayers millions of dollars and removed police from their core duties to protect the public and ensure people not complying with the law were apprehended.

Alarmed by the battles between police and protesters each night on television, NSW Premier Neville Wran told the sawmillers and FCNSW to “get out of the forest before someone is killed”. He complained too late to the media that the issue had gotten out of hand and out of proportion.

Environmentalists claim that the Terania Creek protest persuaded the government to suspend logging operations. That is not entirely true. The prolonged protests were all too much Standard Sawmilling and the loggers. They decided to cease logging operations temporarily. Four days later, Wran called a formal halt to all logging in Terania Creek until Cabinet could meet to discuss the issue. Still, they demonstrated little knowledge of the problem by echoing the green’s line that it was about rainforests, saying:

“…not only is there widespread backing for the conservationists but [Terania Creek] has now become a symbol for their fight to preserve the rainforests of New South Wales”.

Ultimately, the Terania Creek protests would be recognised as the world’s first successful standoff between people and machinery to defend a forest. But the tactic of using direct confrontation had already been used earlier that year at the Wagerup refinery site in Western Australia when 23 demonstrators were arrested for standing in the path of a bulldozer.

In ecological terms, Terania Creek was insignificant compared with the Border Ranges campaign (see Part 2), the major long-term goal of the city conservationists. Yet once Terania Creek became a dramatic media event, with nightly television scenes of blockaders leaping in front of bulldozers getting arrested, the city conservationists quickly realised their chance to capitalise on the growing public interest in the rainforest issue.

FCNSW were at pains to state that it was impossible to consider Terania Creek in isolation. This was because two of the published, yet little publicised, aims of TNAFG were to halt all logging in the rainforest and brush box forests. They wanted a national park covering the whole of Goonimbar State Forest and a significant area of Whian Whian State Forest, even though no rainforest at Terania Creek was going to be logged.

The Terania Creek confrontation was a festering sore for the local rural communities on the north coast. The politicians ignored them, except their local member, who was ostracised within his party. It was a serious issue for many smaller country towns and the primary producers in the areas around them. The decision of the Wran government to preserve large areas of Crown land and prevent exploitation led to increasing friction between farmers and graziers and the state government.

Winning the intellectual battle is useless when you lose the war

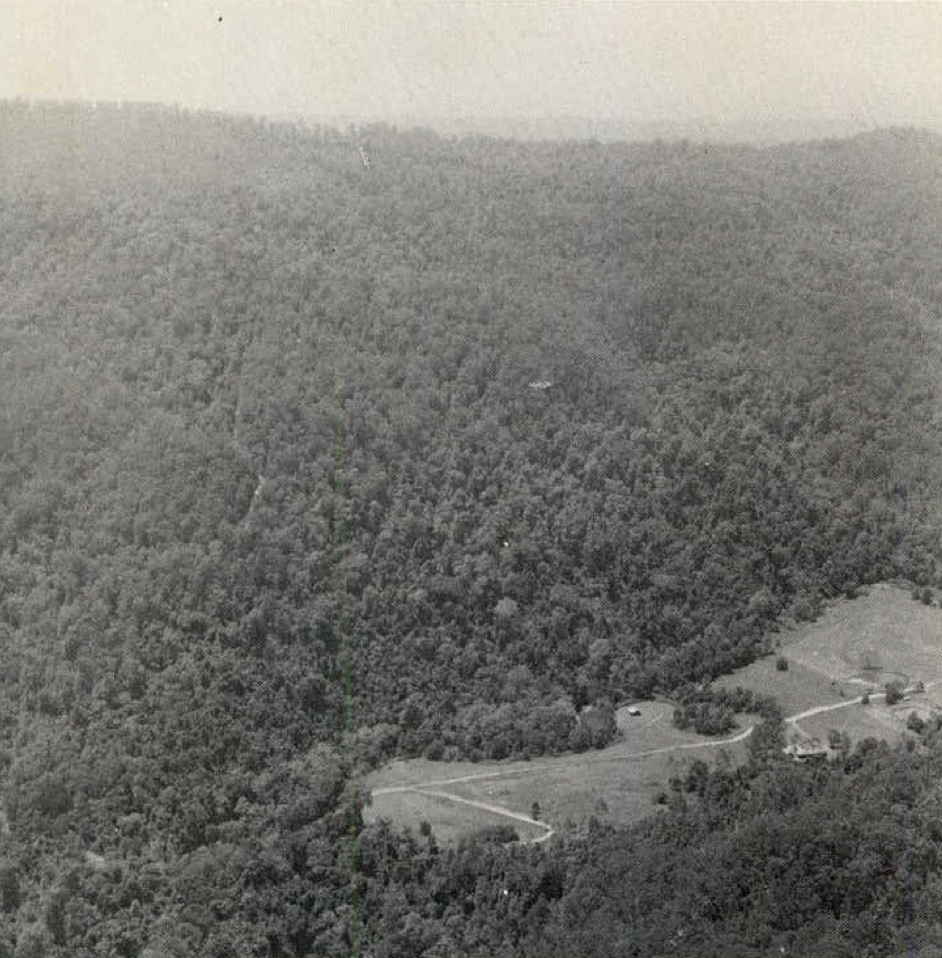

Despite all this coverage by the media about the destruction of ancient rainforests, no one noticed the protesters standing on stumps of trees that were previously logged. Timber-getting in the basin has a long history. Nor did they see the trees targeted for falling were eucalypt and brush box trees, not rainforest trees. The glaring fact was that the area in dispute was just 77 hectares of wet sclerophyll forest carrying brush box trees that had been selectively harvested on previous occasions.

Cedar cutting occurred in the Terania Creek basin in the latter part of the nineteenth century, where trees were felled close to the creek. During floods, the logs were floated down the creek to a boom across the stream at Blakebrook. The cutters recovered them for processing. Henry Vidler and William Kay carried out logging operations with the aid of bullock teams in the late 1920s until about 1930.

The first form of forest management was the allocation of licence areas to sawmills and logging contractors. The timber-getter selected the trees to be removed. FCNSW progressively increased control with the appointment of a forest foreman around 1928 and, subsequently, the appointment in 1935 of a forester located at Mullumbimby. They conducted surveys to determine the extent of the timber resource in the 1940s and 1950s.

From 1943 to 1948, the eastern side of Terania Creek was heavily logged. Thousands of super feet of brushwood species were removed for the war effort. Two army huts were erected on site to house the timber workers. Not long after harvesting operations finished, there was a large fire in the area. To the locals, the area looked like an “unprepossessing mass of undergrowth”. But the forest regrew. It was a tribute to forest management that, in 30 years, further selective harvesting could occur.

(Left) Evidence of previous logging at Terania Creek – note the stump with board holes.

A former farmer who lived next to the forest witnessed the earlier logging operations. He later returned to the area during the protests and was surprised to observe the area on the eastern side of the creek had regenerated. It was a forest of attractive appearance, which indicated the area would not deteriorate into a wasteland because of logging operations.

The timber resource of the area was reviewed on three occasions up until the forest protests. It led to a reduction of 30 per cent in quotas. FCNSW prepared a management plan in 1962 which outlined the sustained yield of sawlogs from the data obtained from resource surveys.

Nevertheless, in 1981, under the State Pollution Control Commission Act 1970, the NSW Government commissioned retired NSW Supreme Court judge the honourable Simon Isaacs to inquire into the Terania Creek rainforest’s values and recommend whether logging should or should not proceed.

The Terania Creek inquiry was criticised for being excessively formal and too long. The process took nearly three years, from November 1979 until April 1982, involving 116 hearing days spread over 17 months, including seven days in the forest and a day and a half at the sawmills. Isaacs took five months to compile his findings and a further five months before his report was tabled in Parliament. Over 170 organisations and people made submissions, and the Inquiry heard evidence from 67 people.

The environmentalists were frustrated with the Inquiry, especially when so early things were not going the way they wanted. They didn’t understand the relatively narrow Terms of Reference given to Isaac. They were upset when he refused to examine issues such as whether all rainforest logging should be banned, whether Terania Creek should be declared a national park, and whether FCNSW should report its financial status.

Like petulant children used to getting their way, a couple of the high-profile environmentalists spat the dummy and withdrew. A witness from the Australian Museum was surly and evasive. He displayed what Isaacs referred to as “unpleasant contempt for cross-examination” when asked to justify his claims against harvesting, having to admit at one point that his interpretation of fire frequency in the Terania Basin was anecdotal. That didn’t stop him on ABC Radio’s Science Show, stating the Inquiry was a “political gambit, an intellectual farce”.

Many submissions were unaware that FCNSW did not plan to harvest rainforest, and the proposed logging was only 77 hectares. However, the campaign’s significance was not its small size but its perceived impact. Notably, it managed to ally north coast new settlers and urban environmentalists and captured the public’s attention on a grand scale.

The Inquiry was no different from other similar inquiries at the time, such as the Helsham Inquiry, which had identical judicial trappings and a significant role for legal counsel. All the environmental inquiries since 1975 followed the tradition of Royal Commissions as part of exercising the executive powers of government.

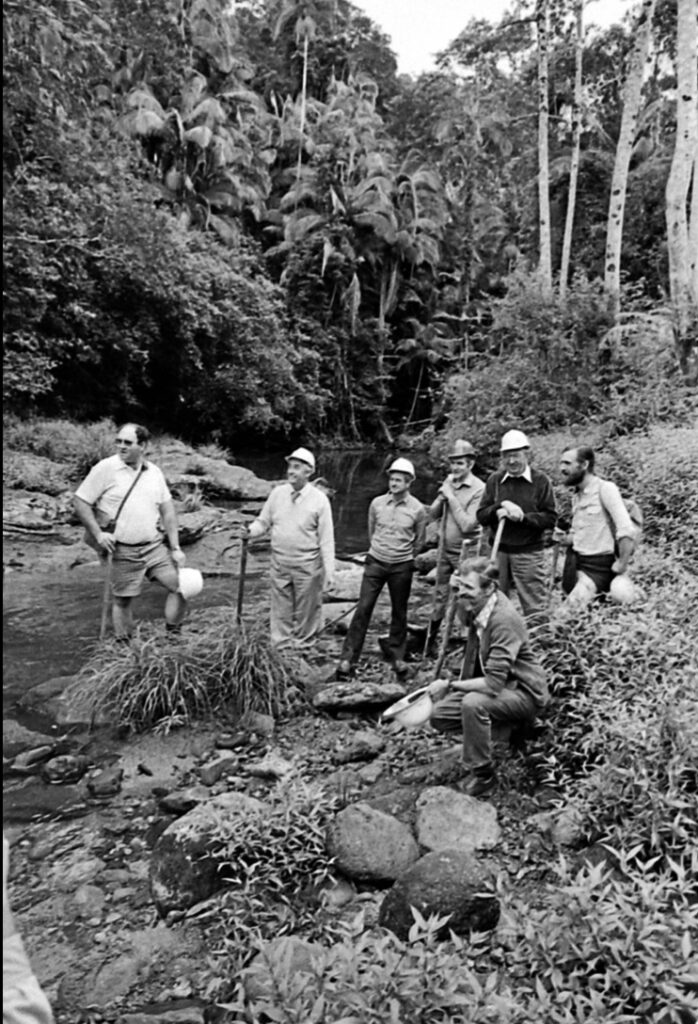

(Right) Charlie Lemair and John Bruce from FCNSW discussing planned logging operations at Terania Creek for Inquiry participants.

In NSW, the modern system of public environmental inquiries was established as an administrative field, separate from the courts, in an overt attempt to distinguish between judicial and non-judicial inquiry functions, but the rules of natural justice still applied to such inquiries.

Nevertheless, Isaac’s inquiry was one of the most comprehensive ever held in Australia and vindicated the management of forests by professional foresters. During the inquiry, FCNSW was asked by the government to prepare a position paper in October 1979. They took the opportunity to remind the government that the practice, outlined in the FCNSW 1976 Indigenous Forest Policy, of phasing out of rainforest logging subject to existing commitments was a mess their masters created:

“The Commission has been caught in the bind of having to meet commitments entered into many decades ago…under the direction from the Government of the day which subsequent Governments have been loath to terminate or reduce because of their important role in providing employment and decentralised economic activity”.

The professional body representing foresters released a policy statement on rainforest logging, arguing it should continue on a sustained yield basis. In addition, they claimed that there should be reservation of undisturbed rainforest areas on the proviso that the government stop maintaining all rainforest logging should cease.

The Department of Forestry at the Australian National University in Canberra held a series of public lectures on forestry matters in August 1979. Lecturer Ross Florence summed up the whole mess:

“..the Border Ranges dispute is a classic example of the way Government, no matter how well motivated it may be in the cause of environmental quality, is unable to reverse established patterns of resource use which would produce a powerful political reaction at a local level”.

At the Inquiry, in one corner was the environmentalist’s star witness, CSIRO rainforest ecologist Dr Len Webb. On the other were the research officers from FCNSW and barrister David Officer. Officer examined Webb for over 20 hours that spanned seven different days. It was a gruelling experience, so much so that Webb’s whole case against logging in Terania Creek was minutely dissected and dismantled by Officer, who revelled in the judicial process.

Webb, however, was on a hiding to nothing once he attended the Inquiry, not as an independent expert, but one that shared the views of the environmentalists. Without realising it, he had allowed Officer to question his authority. Officer knew Webb argued in his submission that Terania Creek was unique and deserved to be reserved. Yet he was exposed for applying general knowledge about ecological processes from other regions in the world and thus lost the argument on using that knowledge in a unique environment. It was a subtle deconstruction but very effective.

One conservationist summed up the situation aptly:

“Poor old Len…he was our ace. World-renowned rainforest ecologist…who would have the temerity to question what he said?…To have his scientific credentials rubbished in a court of law was shocking”.

The dispute that drew the most attention at the Inquiry was the intellectual argument over what exactly defined a rainforest, particularly debates over whether rainforest trees formed the understorey to a canopy of eucalypt trees. The environmentalists argued that brush box was an ecological precursor of rainforest and logging brush box meant logging rainforest. For foresters, arguing their point was difficult because all the public saw on television was a “green jungle”, and they didn’t understand the nuances between hardwood or brushwood, wet sclerophyll or rainforest. The glaring fact was that the vegetation in dispute was shown to be a wet sclerophyll forest carrying brush box trees, not rainforest, and had been selectively harvested on previous occasions.

The area’s resilience was also aptly demonstrated rather forcefully during the Inquiry over a paddock that had been cleared to grow corn before 1942 and subsequently abandoned. Aerial photographs showed the regeneration of woody vegetation. The Inquiry visited the “Corn Patch”, and Justice Isaacs was shown around fifty rainforest species that had successfully regenerated. It was a clear demonstration that if rainforests on fertile soils in the Terania Creek basin were cut down and left alone, the original rainforest plants would be able to return.

While FCNSW won the scientific argument that was painstakingly examined during the inquiry and thus the intellectual battle, they lost the war.

Even though Isaac recommended that logging continue at Terania Creek, much like the Helsham Inquiry, it was ultimately overturned by the executive government, which chose to ignore the highly technical process for the pursuit of the “truth”. Unfortunately, this has been a frequent symptom of the failure of the judicial approach to adequately keep issues “under control” as part of the executive’s political agenda.

The lead up to the Rainforest Decision

In the early 1980s, there were other campaigns to save rainforests in Washpool State Forest near Grafton and in the Hastings Valley near Port Macquarie, which widened the original rainforest preservation issue into a political struggle on resource use.

It all culminated with another forest confrontation on the slopes of Mount Nardi, in the valley adjacent to Terania Creek. The local community at Tuntable Falls formed the Nightcap Action Group to stop the planned logging operations. By this time, the demographics had changed somewhat. The young, unemployed, homeless males that arrived in the early 1980s had a more prominent role in the local environmental campaigns.

Protesters at Mount Mardi. Photo John Seed.

This group was a bit different because they didn’t trust the middle-class protesters in Sydney dictating strategies and controlling the objections at the political level, expressing frustration that intimated a crack in the powerful unity of the varied environmental groups.

They also appreciated the power of the media and realised there was no point in doing anything risky without a camera. So they set up a launch pad for helicopters next to their camp. When they knew logging trucks were on their way, they rang the Brisbane media outlets, who would immediately fly in. Protesters would then happily throw themselves in front of the trucks to be filmed for dramatic effect.

The traditional environmentalists still designed postcards and leaflets and wrote letters to lobby politicians. The emotive language of rarity continued to take hold. For each new protest, they kept arguing that they were saving the last remaining piece of rainforest. But, as with all arguments against forestry operations, there is never any sense of proportionality. They never acknowledge the many flora reserves that had already preserved many hectares of rainforest. Instead, emotional zeal was at the forefront, where the virginity of the forests was falsely highlighted, comparing them to a cathedral with “great columns reaching to the sky”.

Here is one example:

“Right now, these remnant rainforests are being logged mercilessly. The remaining pristine rainforest will be logged out by 1986. Sub-tropical rainforest is virtually clearfelled…The great diversity of animals that depend on mature rainforest are left to die”.

Not surprisingly this emotional campaign successfully swung the balance within the Labor Party cabinet room in their favour.

While the focus was on rainforest logging and preservation, the real agenda was more far-reaching. The forests the environmentalists wanted locked up and converted into national parks contained extensive areas of eucalypt hardwoods. By 1982, only a few mills were heavily reliant on brushwood or rainforest timber. They were the Yarras ply mill in the Hastings Valley, Munro and Lever’s mill at Grevillea, Standard Sawmilling at Murwillumbah and Big River Timbers at Grafton.

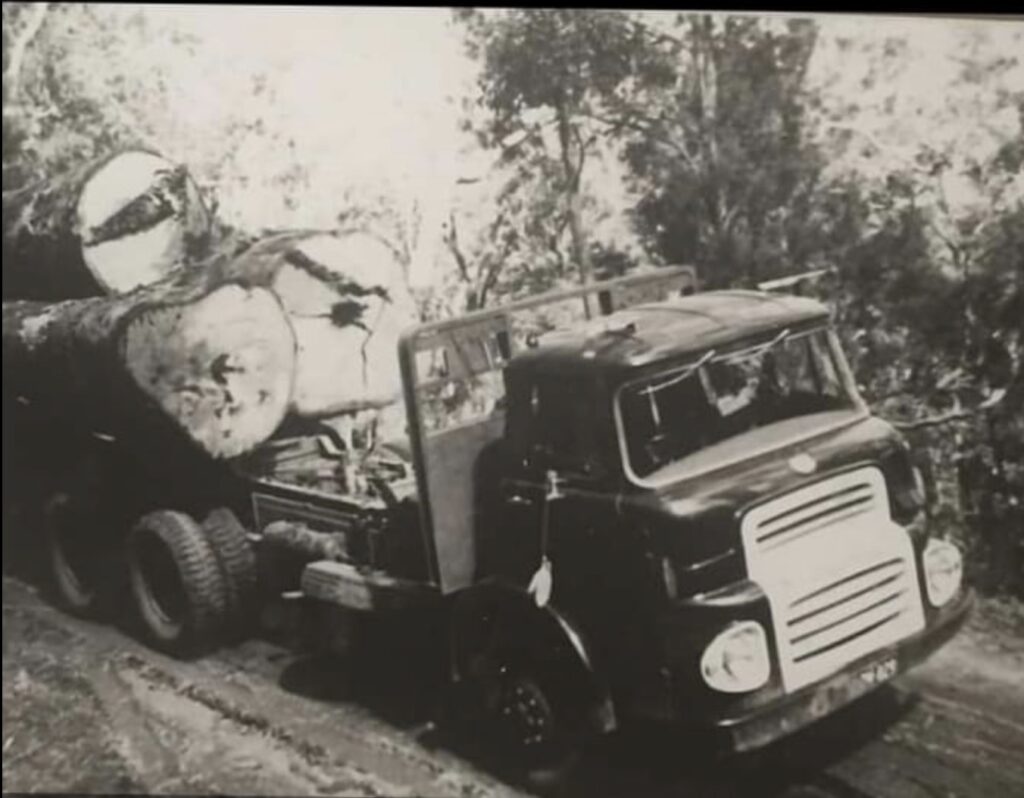

Log truck driven by Clive Brady on its way to the Grevillea mill. Photo courtesy Wayne Brady.

In the Washpool section west of Grafton, the areas sought by environmentalists contained three and a half times the hardwood resources as rainforest timber. CC started arguing that the “Washpool wilderness” was the largest remnant rainforest that had to be saved, only a few months after saying the same thing about the Border Ranges.

In early 1982, fifty “scientists” worldwide put their names to the letter written by CC and addressed to Neville Wran, urging him to halt rainforest logging.

The end of the rainforest argument

Suddenly and unexpectedly, late on the afternoon of 26 October 1982, after a six-hour Cabinet meeting, Wran made his infamous decision – his government would preserve most of the state’s remaining rainforests and rainforest logging would be phased out as quickly as possible. In addition, 93 per cent of the seven areas requested by conservationists, including Nightcap and Border Ranges, would be added to the state’s national parks. Recommendations from the Inquiry and the expertise of FCNSW were bypassed.

A day earlier, the Land and Environment Court had ruled that logging could not continue at Mount Nardi until FCNSW completed an Environmental Impact Statement. While that was a critical blow, the behind-the-scenes manoeuvring sealed the fate of the rainforests.

A month earlier, the cabinet’s rainforest sub-committee, which Wran chaired, met with the leaders of Sydney’s conservation groups. They were given a list of seven non-negotiable rainforests they would defend at all costs. Protesters were active in Nightcap Range, and FCNSW fought the environmentalists in court on several fronts. At the time, the state’s unemployment rate was nudging 7.5 per cent. The Terania Creek Inquiry provided plenty of information to develop a balanced rainforest policy. But cabinet was divided on rainforests policy.

However, Wran’s most influential advisor was his wife, Jill. She had close connections with prominent environmentalists. Jim Sommerville was the accountant for Qantas when Jill Wran worked for them as a marketing executive. Despite Sommerville allegedly trying to unduly influence the Inquiry by making statements to the media that were critical of the way it was being conducted and Isaacs threatening to sue him for defamation, he remained a close confidant of Jill’s. It was through these relationships that Sommerville and Dunphy gained access to, and influence, over Wran. They took him on private trips to the bush to get into his ear.

Announcing the Rainforest Decision, Wran said,

“The Government believes that the rainforests are part of an irreplaceable heritage”.

He also admitted the role of his wife, saying:

“There was only one decision, if I’d taken any other decision, I think my home life might have been imperilled”.

After the announcement, the leader of the State National Party said, “today marks the day the environmental lobby took over the government of NSW”, while John Laws called it “a plague on the house of the greenies”. The protesters were ecstatic, hailing the decision “as a shining example for the rest of Australia and the world”.

Pitifully, and in a betrayal to Labor party constituents outside the cities, Wran was only interested in his legacy, telling the Labor Party State Conference:

“When we are all dead and buried, and our children’s children are reflecting on what was the best thing the Labor Government on NSW did in the 20th century, they will come up with the answer that we saved the rainforests”.

A lot of credit was given to Wran for “saving” the rainforests. But his decision was simply a means to end the violence and sabotage occurring in the forests. The costs were people’s livelihoods trying to continue doing what was legally allowed.

The Rainforest Decision removed 117,000 hectares of rainforest from timber production. Even though the government allocated $1 million to offset the losses to the timber industry, promote the development of technology for handling alternative timbers to assist affected companies during the transition and buy private property to plant pines, it was supposed to ensure no jobs were lost because of the conversion of areas from state forest to national parks. However, soon after the decision, the Grevillea mill closed, and it was estimated that the region lost 600 jobs.

Don Day, the local member at Casino, was one of the staunch supporters of the local timber industry in cabinet (for more detail see Part 2). After surviving WWII, Day was ready for political fights to defend his constituents. As a minister, he had many great battles. The rainforest war put him at loggerheads with his city-based colleagues within the Labor Party. His last fight was his most significant political defeat, which led to an irreparable war with Wran. After October 1982, exhausted and finally defeated, Day retired from politics in 1984.

Science means nothing in politics

The reality was that the rainforest decision on the north coast was purely political, where the resolution was resolved at a state-wide level, with only a token involvement of the people most affected.

There was a straightforward irony lost in the dramatic protesting and representations made by the various groups about the objection to the Terania Creek logging operations. It was the unintentional recognition that even though parts of the forests were ruthlessly logged during WWII without any of the environmental controls of the 1980s, they still managed to regenerate back to a forest that, in the eyes of the protesters, had the same ecological values as an undisturbed or virgin forest.

The effect of Wran’s decision was to hasten the phase out of routine rainforest logging that FCNSW was implementing with the least disruption to established industries. If it had been left to run its course, the process would have been completed by 1992. The annual supply of brushwoods had already been reduced from 110,000 cubic metres in 1975 to 60,000 in 1980.

Despite the heavy promotion of tourism as an alternate source of employment in the region, that sector only accounts for less than three per cent of the total state employment. As a result, the only growth sector in the area has been the public sector. The public purse supported about 40 per cent of the regional labour force in 1986, and that sector has since grown.

The problem with Wran’s rainforest decision was that it also significantly affected the hardwood supplies. FCNSW had to cut the quotas of hardwood sawmillers by 85,000 cubic metres a year after a total of 435,000 cubic metres of hardwood timber were lost. Grafton sawmiller Spiro Notaris outlined in 2011 how his company lost 30 per cent of its hardwood resource because of the Rainforest Decision. All sawlog allocations were terminated in the former Kyogle Management Area and taxpayers saw an immediate 34 per cent decrease in royalties obtained by FCNSW from the north coast.

A final word – the question of recovery

Another major issue throughout the rainforest campaign was the perception of how sensitive a complex rainforest ecosystem was to logging disturbance. Environmentalists saw logging as permanent destruction, and ecologists such as Webb and Recher questioned the veracity of FCNSW scientific work, particularly that of silviculturalist George Baur.

Baur was the key FCNSW spokesman engaged in public debate during the rise of the conservation movement in the 1970s. A staunch follower of the scientific method to maintain ecological integrity, he was an expert on the ecological basis of rainforest silviculture and introduced comprehensive silvicultural guidelines. In addition, Baur was pragmatic and argued for a balanced approach in response to the competing demands on forest resources to develop and implement the FCNSW environmental policies. In doing so, he was instrumental in creating Flora Reserves within state forests.

While he received a constant barrage of criticism from activist academics and environmentalists, his research, experience and reports meant he and his views were highly respected.

Baur’s work showed that rainforest revegetated well and returned the range of species present before logging. Still, a challenge remained on more heavily impacted areas such as trails, snig tracks and log dumps. Several FCNSW employees published papers in scientific peer-reviewed journals on that topic.

For example, a study compared the dynamics of tree diversity in undisturbed and logged subtropical rainforests. Changes in the variety of trees were compared under natural conditions and eight silvicultural regimes over 35 years. In the treated plots, the basal area remaining after logging ranged from 12 to 58 square metres per ha. In three control plots, species richness differed little over this period.

Also, many trial plots set up by FCNSW demonstrate that rainforests grew back more than adequately. However, work by George Baur in the 1950s and 60s showed that rainforests take a long time to reach their previous unlogged condition if heavily logged. That is why a lighter selective harvest system called the 50 per cent canopy retention was introduced (see Part 2).

When the North East Forest Alliance (NEFA) successfully gained an interim court injunction in 1990 to halt the logging of hardwood and rainforest in a section of Washpool State Forest adjoining the new Washpool National Park, the stage was set for another lengthy and expensive court battle to determine the legal status of rainforest logging. Finally, however, FCNSW, NEFA and the court agreed on a unique dispute resolution to set up a committee of scientific experts to study the regrowth of a logged rainforest area.

As members of the committee represented both sides of the debate, a golden opportunity existed for both sides to work together and closely examine a typical case study of logged rainforest three to six years previously. Of the study’s 200 hectares of logged forest, 93.6 per cent was selectively logged with moderate to low disturbance levels. In most areas, the committee found that regardless of impact, the natural vegetation process was well advanced and that the natural revegetation process underway for more than four years was adequate and subsequent growth would be satisfactory to regain a rainforest canopy over time. Only 1.15 per cent of the logged rainforest required help through supplementary planting. Further monitoring a year later showed species diversity increasing.

The FCNSW and foresters had once again shown that the scientific credentials of their management stood up to scrutiny. While it wasn’t perfect, they strived to do so to meet the challenges and needs of modern society and ensure the environmental benefits remained in time. But that meant little in the cut and thrust of politics. The fight over Terania Creek showed how politicians could ignore professional forest management to seek short term outcomes that suited their own egos and personal needs, spruiked on by environmentalists who were loose with the truth, and used questionable tactics – all with the support of a sympathetic media.

Robert, an excellent story highlighting the ecofascist behaviour of the so called non-violent activists over past decades.

The political bastardry and the complicit media are other common threads that have also endured through the history of forest lockups over the past 40 years. The radial climate change devotees and GreenBC news makers don’t have the remote cover of the forests to hide their criminal and complicit roles in recent protests.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-12363349/ABC-fire-filming-environmental-extremists-invade-home-energy-company-boss-act-designed-threaten-me.html

Thanks Robert. We need articles like yours that document what has happened and why. There is a situation here in WA where sustainable, selective timber harvesting of jarrah on State forests will cease in 2024, yet Politicians will allow the clearing of State forest for the mining of bauxite to continue. Frank Batini

Thanks Robert.

They were my dad’s, Bill Cleeland, trucks carting out of there then.

Regards Ashley Cleeland.