Introduction

Earlier this month, I outlined a historical account of the utilisation of rainforest timbers in New South Wales (NSW) and the challenges foresters faced to ensure the cut was sustainable. Rainforest timbers were in high demand for various purposes, such as fine furniture and cabinet work crafted from red cedar and rosewood or boats planked and decked with white beech, decorative veneer, furniture, sports gear, craft use and specialist military purposes.

Some of these uses are part of our heritage. However, very few people know that high-quality brushwood timbers from the north coast now furnish some of the premier venues in the country. Examples include white birch (Schizomeria ovata) veneer in the Concert Hall of Sydney’s Opera House; tulip oak (Argyrodendron peralatum) for the Canberra Art Gallery; and yellowwood (Flindersia xanthoxyla) as flooring for the Homebush Olympic Stadium in Sydney.

(Left) Great Hall at Parliament House, Canberra. The timber walls that surround the two levels of the Hall are made from a variety of timbers, including lined white birch.

Even after locking up the rainforests on Crown land in NSW, the new Parliament House in Canberra used a range of rainforest timbers.

(Right) Despatch box used in the House of Representatives is made of rosewood. Photo Auspic.

They included silver ash (Flindersia schottiana), black bean (Castanospermum australe), coachwood (Ceratopetalum apetalum), blush tulip oak (Argyrodendron actinophyllum), camphorwood (Cinnamomum oliveri) and white birch. Rosewood (Dysoxylum fraserianum) was used to line office wall panels. It came from private property logged by Standard Sawmilling Company before Premier Bob Carr imposed an interim conservation order under the Heritage Act 1977.

In a building that expressed a national identity and character through its use of native timbers from all over the country, the politicians had no idea where they originated. They failed to comprehend the irony of their state counterparts quietly orchestrating the eventual demise of rainforest management in Australia, starting with the Helsham Inquiry in the early 1980s.

Ending rainforest logging typifies the preponderance of politicians to lock up native forests based on non-scientific calls from environmental groups who led them to believe that a lack of management is a sound ecological practice.

However, as eminent environmental historian Eric Rolls wrote, the reality is the entire Australian landscape has had human management for millennia:

“The one thing this is often forgotten in the never-ending arguments about the value of forests is that under Aboriginal management, no square metre of soil in the country was left to care for itself. For thousands of years, Australia was intensively managed by people who knew what they were doing for the land and for themselves. To lock up a forest is to confine it in an unnatural state”.

A study of the political machinations and battles fought by foresters over the management of rainforests in NSW shows how poignant Rolls was. Foresters suddenly found new settlers living on the doorstep of the forests, who became their enemy. So were the city media. But, of course, they have always had enemies. In the early days, the first enemies were the settlers who targeted timbered areas on ridges above the valleys to open for grazing purposes and their fellow bureaucrats in the Lands Department who promoted this wanton clearing.

Forester’s relationship with the timber industry often bordered on hostility mainly due to attempts to enforce new policies, extract higher royalties, reduce log quotas, or accept all marked trees, not just profitable ones. In addition, a complex set of social and political considerations always tempered the forester’s attempts to supply timber. The conflicts between the warring parties were mainly suppressed and fought behind the corridors of forestry offices, sawmill buildings or in parliament. It is hardly the evidence to support the oft-repeated claims by environmentalist activists that the Forestry Commission of New South Wales (FCNSW) was a captured bureaucracy.

An alternative view of rainforests

While environmentalists claimed their direct action led to the preservation of rainforests, they never acknowledged that FCNSW worked hard before them to ensure that substantial areas were preserved from further logging on state forests through Flora Reserves and Forest Preserves. They also provided active assistance to have representative sites dedicated to a national park. As a result, Werrikimbe National Park and extensions to Dorrigo, Gibraltar Range and Barrington Tops National Parks were all dedicated, either as FCNSW initiatives or with maximum assistance to the Lands Department and the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS).

Foresters had Wiangaree State Forest dedicated in 1917 and managed to protect the forest from clearing. They did, however, recognise that unlogged areas represented the best development of sub-tropical and warm and cool temperate rainforests in NSW and were worthy of preservation. At a meeting in Kyogle in 1971, the North Branch of the Institute of Foresters (IFA) recommended the creation of a Flora Reserve at Grady’s Creek as an excellent example of virgin rainforest. The minister accepted the recommendation, and Grady’s Creek and Mount Nothofagus at nearby Donaldson State Forest, became Flora Reserves in 1973.

It is no surprise that Wiangaree State Forest became the centre of attention of environmentalists in the 1970s, as it is situated in a truly remarkable part of Australia. Mount Warning created the landform when its volcano poured its contents to form a plateau ranging from 700 to 1,000 metres in altitude. It now includes the upper reaches of the western arm of the Richmond River. The state forest was one of the first dedicated in the state and is bounded to the east by steep high cliffs, which drop off into the upper reaches of the Tweed Valley.

Remarkably, the exposed basalt plateau section is almost entirely sub-tropical rainforest grading into a warm temperate rainforest, an uncommon feature on the numerous ridges and spurs at lower elevations elsewhere on the north coast. There are occasional patches of cool temperate rainforest on the higher exposed peaks and in the headwaters of the streams with majestic antarctic beech (Lophozonia moorei) the dominant tree.

A combination of predominantly rainforest, mountain streams and magnificent panoramic views eastward to the coast and north and west into Queensland make the area one of very high scenic beauty.

The forest, nonetheless, has a long history of logging dating back to the turn of the nineteenth century when cutters sought the highly prized red cedar and other species such as white beech, native teak (Flindersia australis) and hoop pine (Araucaria cunninhamii). Single tree selective operations were mainly focused on the western edge of the forest, which was easily accessible for the local sawmills in the area.

From the 1950s until the mid-1960s, logging shifted to an extensive area of wet sclerophyll forests and sub-tropical rainforests in the western foothills.

In 1963, FCNSW began building a road onto the plateau section from the west to access extensive rainforest areas to supply commitments for Standard Sawmilling Company based in Murwillumbah and Munro and Lever at Grevillea. While there was no initial opposition, not long after, the Kyogle Community Development Association requested the newly established NPWS dedicate a national park stretching along the border with Queensland from Mount Lindesay to the Tweed Range and linking with Lamington National Park across the border.

(Left) Jim Gasteen.

Nothing resulted from this request, but this changed when a second logging road on the Wiangaree Plateau commenced in 1972 from the east. Local farmer Jim Browning rang his former farming neighbour Jim Gasteen:

“If you want to get a last look at your favourite rainforests, you’d better stop buggering around with land in Queensland and get down here fast. The bulldozers and chainsaws are lined up to start logging as soon as they gouge a road up Horseshoe Creek spur to the crest of the Tweed Range”.

Gasteen had witnessed the changing moods of the Tweed Range from the veranda of his farmhouse at Stony Chute for years, and his family believed the rugged mountains had become, in their eyes, a sacred territory. He wrote in his book that it was unthinkable that men armed with chainsaws and bulldozers could be let loose in a place of such beauty:

“…his hair flew in the air and I bristled like an old scrub pig with the dogs in behind”.

He wrote to the FCNSW Commissioner to express his concern. He sought to preserve the entire plateau as a national park “wilderness” as a logical extension to the existing Lamington National Park across the border in Queensland. The Commissioner rejected his request but admitted that parts of the area would develop for tourism and recreational use in time, using the road to the plateau.

Unsuspectedly at the time, the future battle lines over rainforests began through this exchange of reasonable and gentlemanly correspondence.

Unperturbed by the negative response to his proposal, Gasteen contacted Russ Maslen, President of the Byron Flora and Fauna Conservation Society and an Honorary Ranger with the fledgling NPWS. They quickly formed a new organisation of five members called the Border Ranges Preservation Society (BRPS). They tried to get support to convert Wiangaree State Forest and adjoining areas into a national park.

Over three months in early 1973, a spate of letters were published in the local newspapers and sent to FCNSW and the minister from BRPS, local environmental groups, and the National Parks Association. They all criticised the logging of rainforests, raising the issue of floods and clear-felling on other dissimilar forests. Some of the letter writers were rather poetic:

“What God hath wrought – what man has destroyed”.

Maslen suggested:

“Unless some action is taken very soon, Wiangaree will consist of a mosaic of patches of smashed branches and timber not worth the miller’s saw”.

There were also letters of support for the industry. One writer expressed concerns about the misrepresentations, inaccuracies, and emotional language. The local District Forester organised a tour of Wiangaree State Forest for representatives of local councils, regional bodies and the media. He explained past mistakes, current practices and future recreational and logging development proposals with a barbeque lunch provided. However, BRPS complained that it was improper for FCNSW to promote its activities at public expense, saying, “we have elected representatives for that purpose”.

The minister rejected the BRPS proposal for a national park. Even the leader of the Labor opposition, Pat Hills, was pleased with FCNSW’s management of Wiangaree State Forest. After an inspection of the forests, he promised he would do all he could to retain FCNSW management and ensure employment for the several hundred people in the timber industry.

Despite sympathetic local media coverage, the BRPS campaign fizzled out. However, it was suddenly reignited when Hills backflipped, declaring in a by-election speech in late January 1974 that:

“Labor would take immediate steps to prevent exploitation detrimental to the environment and natural beauty, such as logging activity of the Tweed Range rainforest”.

He requested the minister cease logging operations above 650 metres and declare a national park.

The battle shifts to the city and glossy magazines

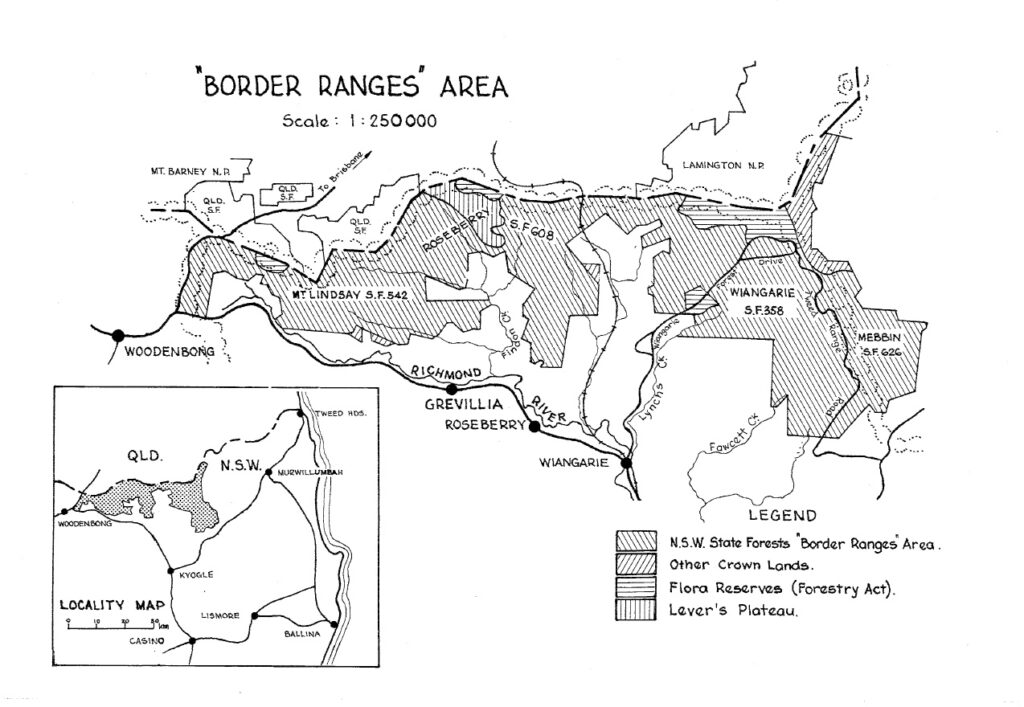

Meanwhile, after appeals for help from the BRPS, the Sydney-based Colong Committee (CC) sent Alex Colley to visit the area, and he wrote glowing reports for conservation magazines. Geoff Mosley, from the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF), recommended a public inquiry. But it wasn’t until the Federal Committee of Inquiry into a National Estate was established in May 1973 that further impetus for reservation gained momentum. Two of the Inquiries members, Milo Dunphy and Judith Wright, visited the state forests near the Queensland border, promoted as the Border Ranges. In its September 1974 report to parliament, the Committee recommended:

“…that all forest authorities recognise the urgent need to manage, in the most conservative manner, the remaining rainforest areas of Australia”.

The Committee also recommended National Estate grants to conservation groups. Consequently, the BRPS obtained a grant of $5,000 from taxpayers to prepare a report for a proposed national park. The report was amateurish, but it managed to bring the Border Ranges campaign to Sydney, where the CC decided to get involved.

Representatives of 50 conservation societies formed the CC in May 1968. Over the next seven years, they succeeded in defeating a limestone quarry in the Blue Mountains and an FCNSW proposal to establish a pine plantation on the Boyd Plateau.

(Right) Milo Dunphy. Photo Caroline Begg.

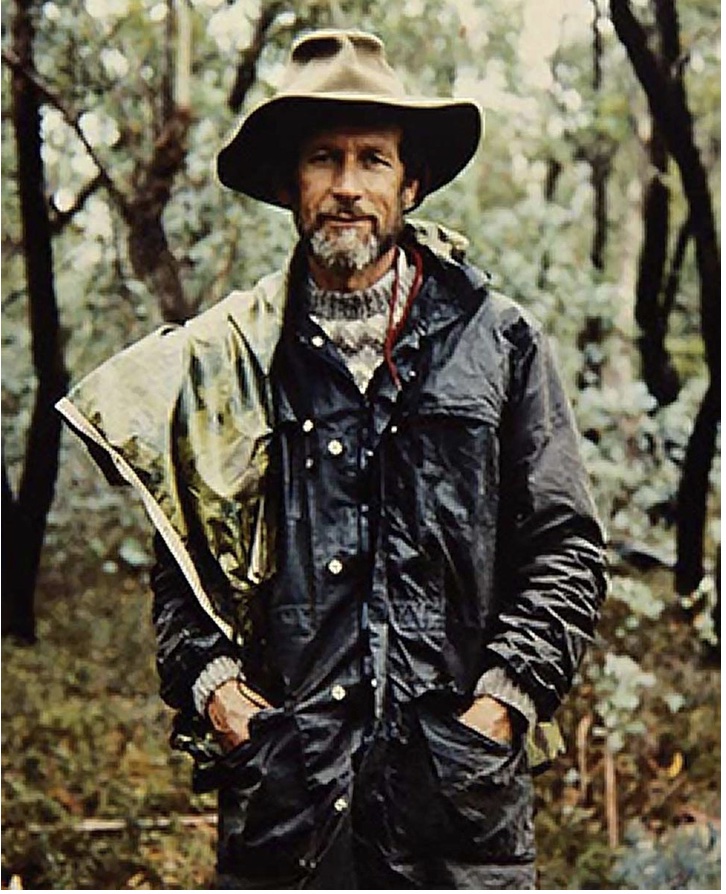

In April 1975, the CC decided to campaign for an extensive rainforest national park on the NSW-Queensland border. They commissioned a photographic study of the area. They used it in slide shows, pamphlets, articles, media releases and large posters, which were an essential source of funding for the group. The proposal involved a group of state forests – Wiangaree, Rosebery, Mount Lindesay, Donaldson and Koreelah in the far north-east corner of the state. Half was rainforest, and the other half was wet sclerophyll forest communities.

The area in which they lie was commonly called the Border Ranges. Wiangaree State Forest was contiguous with Lamington National Park over the state border, one of the first national parks declared in the country in 1917.

What started as an expression of concern to FCNSW over the visual and ecological effects of roading and logging at Wiangaree had built up over the next three years around the principle and practice of logging forests and alternative uses of the forests, especially dedication as national parks. This was not new. In 1959, the National Parks Association of Queensland had unsuccessfully lobbied the NSW Department of Lands to establish a national park adjoining Lamington. But this time, things were about to get very ugly and personal between the protagonists.

The October 1975 special issue of the National Parks Journal ran a story promoting a Border Ranges National Park covering some 33,000 hectares. But the real focus for getting the issue in the minds of the urban voters was a series of media stories. The first was published in the Sydney Morning Herald by the paper’s first environment writer and friend of the CC, Joseph Glascott. The front-page story in December 1975 was titled “Proposed Park threatened: the last rainforest gets the chop”. Glascott relied on information fed to him by the CC’s Jim Sommerville without seeking the forester’s side of the story. Using hyperbole straight from the activist’s mouths, he wrote:

“The fate of the last substantial rain forest in NSW is hanging in the balance…Unless the State Government acts soon it may be too late to save the magnificent timber stands and luxuriant vegetation of these rain forests“.

On the same evening, ABC Television ran a story on their news bulletin for four minutes. The next day, Glascott wrote another two-column article about the economics of a proposed road headed “Rainforest logging road a waste says Colong Man”.

Before the 1976 state election, the new Labour leader Neville Wran outlined his party’s environmental policies. After visiting the Border Ranges in November 1975, he declared:

“..the forests of the North Coast should be managed in perpetuity as a forest resource, not merely as a timber resource, and all their values maintained”.

Meanwhile, only three days before the election, The Minister for Forests and Lands, Col Fisher, announced approval to construct the Levers Plateau Road. However, after winning the election and toppling the Liberal-National coalition, the Labor Party delayed a decision until after their annual state conference. A motion endorsing the Border Ranges National Park proposals was defeated at the conference.

Dithering through committees, reports and investigations

The government appointed an Inter-Departmental Committee to examine the need to build the road to Lever’s Plateau in Roseberry State Forest. The Director of NPWS overshadowed this process by sending a team to the Border Ranges in September 1977 to study the area and provide a report. Unfortunately, the officers went beyond their brief to recommend that logging licences not be renewed at the end of their terms. The Director tried to keep the report from the public, only to find out the team had already sneakily leaked a copy to CC, who then forwarded it to Glascott for a story.

The continuing campaigning methods varied widely. A who’s who of the city-based environmental groups were involved – Milo Dunphy and the CC, Peter Prineas from the National Parks Association, Dick Thomson’s Ecology Action Group, Vincent Serventy’s Wildlife Preservation Society, Friends of the Earth and the National Trust. Dunphy pushed for confrontation while others took a more pragmatic view, exploring politically acceptable solutions such as locating alternate timber supplies.

FCNSW received little recognition, even though they had already created a recreational forest drive through the virgin rainforests across the plateau and created walks and reserves that form the primary basis of visits to the national park today. In addition, they prepared a management plan for the Kyogle district to provide information for the Inter-Departmental Committee. Essentially, the plan outlined the short-term requirements to continue supplying timber quota arrangements and explored alternatives and their implications.

Regardless, the campaign went national after the support of the only national environmental organisation entered the fray. ACF published a special issue of their magazine Habitat about the Border Ranges containing ten articles by members of the CC and the BRPS. In addition, their campaign helped provide momentum after the FCNSW announced proposals to log virgin hoop pine on Levers Plateau, an area sawmiller John Lever supposedly decided not to log in the 1940s.

Meanwhile, the Whitlam Commonwealth Government funded a scientific investigation into forest areas needed to preserve endangered flora and fauna. It was led by a close friend of Dunphy, Fred Bell, from the University of NSW. So, it was no surprise that the most important of the four nominated habitats was the Border Ranges claiming the environment needed such reserves to maintain the biological diversity of native forest ecosystems.

The environmentalists did little to help their cause by making wrong or grossly exaggerated claims to discredit FCNSW management practices. Not that FCNSW were any good at defending the allegations in the beginning. They did start to rally and organise a structured defence against the claims. They referred to the recovery of rainforest stands selectively logged a decade earlier without any soil erosion, which supported a profusion of bird life, and the retention of unlogged strips along roads, streams and exposed escarpments. Visitors were actively encouraged to look for themselves.

While FCNSW strongly believed that the government would resolve the issue in their favour, based on the Inter-Government Committee Report, allowing them to continue managing the forests under clear policy guidelines, the government was keen to see the end of the persistent campaigning over the rainforests. Therefore, at the start of 1978, the Premier instructed his minister to create a small national park and ensure there was no loss of jobs in the timber industry. Jack Henry, the Chief Commissioner of FCNSW, led the negotiations.

Firstly, Henry offered to purchase the remaining eight years of Standard Sawmilling’s brushwood quota. The other rainforest miller, Munro and Lever’s, had been allocated the resource on Levers Plateau, which contained an excellent stand of hoop pine. There were also plans to meet their quota by logging Grady’s Creek Flora Reserve. In exchange, FCNSW offered to spend $2 million planting hoop pine if Munro and Lever voluntarily gave up their allocation on Levers Plateau. In addition, a new national park would be declared on the border for 50 kilometres at an average width of only two kilometres width which was derisively called “Snake Park” by the environmentalists. The proposals were part of an inquiry that called for public submissions.

The IFA members who had initially recommended the reservation of Grady’s Creek because of its unique ecological interest were very concerned about the precedent that its revocation would create.

They believed the political expediency that allowed Grady’s Creek Flora Reserve to become expendable only played into the environmentalist’s hands. The environmentalists argued that the process was only about protecting the sawmilling industry, not the rainforests.

The announcement of an Inter-Department Committee initially overjoyed the environmentalists. They believed it was a way to find solutions to environmental, industry and employment issues raised in the Border Ranges national park proposal saying, “after years of struggle,” the state government had a policy for an “adequate parks system on the north coast”. But, at the same time, they lamented the “interruption and opposition from various interested groups” – landowners, local council, timber industry, Forestry Commission and certain MPs, not to mention the local press.

But that joy quickly dissipated when they realised their arguments were facile and insufficient to warrant changing the status quo. They made outrageous accusations about a “secret inter-departmental committee” and that the most powerful department represented – in this case, Forestry – unduly influenced a recommendation in their favour.

Two CSIRO scientists, Dr Len Webb and Mr John Tracey, both publicly supported the dedication of the Border Ranges as a national park claiming the “remaining unlogged rainforests in Australia should be preserved intact for posterity as part of the world scientific heritage”. They criticised FCNSW for making “outdated ecological generalisations, special pleading and using a convenient selection of forestry literature mainly from the FCNSW itself”. They argued that FCNSW’s repeated claims that selective logging did not interfere with the forests’ scientific value and ecological integrity were wrong. They wrote:

“There is no scientific evidence available to sustain these claims; it is an open question, and as such, any claims in favour of logging cannot avoid being based on pseudo-scientific reasoning and expediency…The 50 per cent canopy retention practice is “illusory”.

The Inter-Departmental Committee ultimately recommended logging continue, and predictably Milo Dunphy immediately went on the attack describing the decision as “one of the most disgraceful environmental decisions ever seen in Australia”. He argued that the forestry case for logging was “knocked to pieces at the inquiry by a dozen leading scientists, and the case for total preservation was clearly established”.

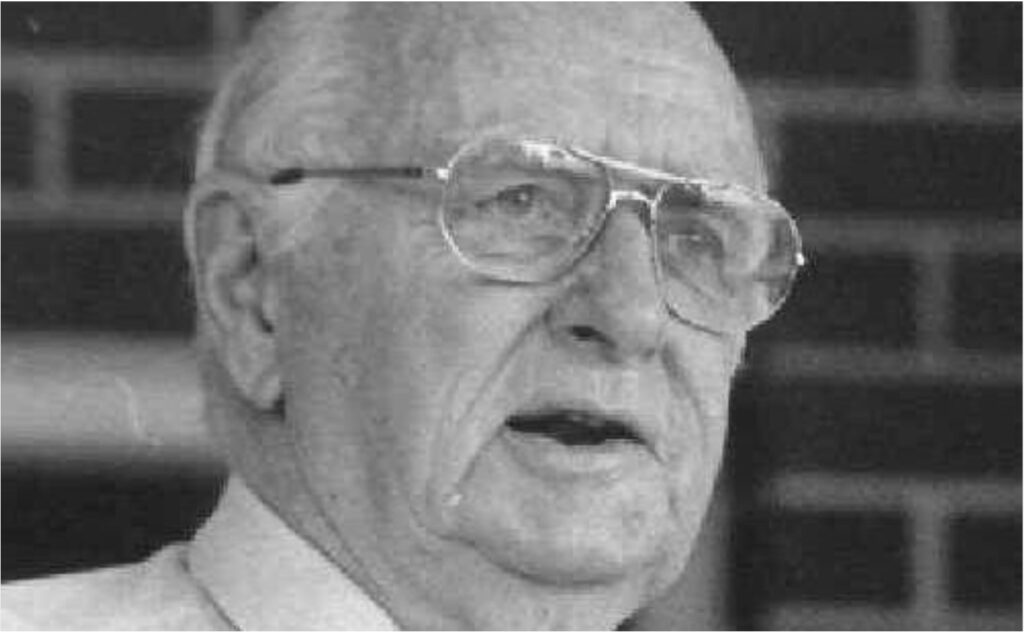

Don Day.

Not happy with the decision, CC turned to political threats. They advised three sitting Labor members in swinging seats that they would run campaigns against their party at the next election unless they reversed the Border Ranges decision. In the firing line was Labor’s local member for Casino Don Day. In one of the biggest political upsets of the time, Day came from political obscurity to win the traditionally safe Country Party seat in 1971 on a low winning margin.

The Country Party had always held the seat. The Electoral Commission abolished the seat in a redistribution in 1968, but they reinstated it in 1971.

Day retained the seat when Labor swept to power in 1976, keeping his small margin of 1.6 per cent, and became Minister for Decentralisation and Development and Minister for Primary Industries. He was one of the few rural-based elected members of the Labor Party. Consequently, in Cabinet, he had to singularly stare down his city-based colleagues who were happy to see the Border Ranges locked up and businesses closed.

Before the October election in 1978, environmentalists in the Kyogle-Lismore-Mullumbimby area ran a candidate against Day. However, Day received nearly 58 per cent of the primary votes, and he went on to comfortably win and retain his seat with an 8.1 per cent swing in his favour to remove the marginal status of his seat. The win confirmed the solid local support he had for his pro-logging stance. The independent green candidate only received 1.6 per cent of the primary vote.

Day’s result was not surprising. A poll of residents in Lismore in August 1979 on Terania Creek logging showed 62 per cent in favour of logging, 21 per cent opposed, and 17 per cent did not know. The survey was carried out for the Associated Country Sawmillers by Dr Roger Munro of the Northern Rivers College of Advanced Education and was surprisingly accepted as an objective study by the environmentalists.

Day fought “tooth and nail” for the timber industry, lobbied ministers and arranged protests over establishing new national parks at Washpool and Nightcap National Parks. The environmentalists believed Day was the “Cabinet’s greatest protagonist for the destruction of NSW forests” and an “exploitation-orientated in the worst traditions of the Country Party”. He was in parliament for five terms being the first long-term Labor Member of Parliament between Newcastle and the Queensland border.

But as Part 3 outlines next week, Day’s strident support for the timber industry meant little in the grand scheme. For Day and the industry, things changed for the worse when FCNSW made plans to harvest a small area in the Terania Creek basin at the Nightcap Range.