“History will be kind to me for I intend to write it” ― Winston S. Churchill

Introduction

One of the great joys I have experienced during my working career and travels around Australia has been the opportunity to walk through rainforests. There is no better feeling. While protected from the heat of the day, or from bitterly cold winds, the chance to walk beneath the towering trees under a closed canopy of large shady leaves allows the opportunity to listen to the cacophonous bird songs. There are varied tunes, from the mournful catbird and the melodious whipbird to the continuous gurgling of the wompoo fruit dove. And there is no greater joy than to hear the complex artistry of the lyrebird – the world’s mimic expert – that stops you in your tracks and puts you in a trance. They are a joy to visit. They are also a joy to work in.

Many rainforests are now in reserves. And in New South Wales, every time you visit a rainforest reserve, there is a reminder of the decisive “rainforest battles” in the late 1970s and early 1980s that saved them from the timber industry.

As the green movement celebrated the 40th Anniversary of Premier Neville Wran’s infamous Rainforest Decision in October 1982, I was house-sitting at Kyogle and Ballina, not far from where the forest protests took place. I used the opportunity to talk to some of the people who were part of the ordeal. As a result, I can reveal that the truth about those events is a much different story from the narrative portrayed in books, media articles and social media. It wasn’t simply a “David and Goliath” contest between the hippies versus the rapacious foresters and a cashed-up timber industry.

(Left) Brindle Creek, Border Ranges National Park.

This is Part 1 of three parts. It is deliberately written as a backgrounder. Please forgive the length of this essay, but I believe it is important to flesh out the history and background of rainforest management in New South Wales to put into perspective the challenges foresters faced in managing the rainforests and why they were in the position they found themselves when under attack.

Early timber exploitation

Surprisingly, the earliest settlers found the hardwood timbers in the new colony based around Port Jackson too crooked, too hard to work and too damaged by fire to be utilised. However, once timber cutters discovered red cedar (Toona ciliata) on the Hawkesbury River flats they discovered a magnificent timber that was easy to work. Booming development in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane fuelled the demand for timber, and red cedar was highly sought after. They were giant trees of such magnificence that convict gangs were set out to cut them down.

Cedar built houses, hotels, pigsties, cow sheds, paling fences and packing cases by the thousands. Cabinetmakers used it to make the finest furniture they could produce. It earnt great respect, however its use was profligate. When the gold rush arrived, the price quadrupled.

Red cedar, however, did not grow thickly in the rainforest scrubs. A good stand averaged one to the hectare over numerous hectares of dense rainforest. Because the cutters just focused on cutting cedar, other suitable timbers, such as rosewood (Dysoxylum fraseranum) and hoop pine (Araucaria cunninghamia), were overlooked, as were many eucalypts in the adjoining sclerophyll forests.

The government didn’t charge timber royalties, but there was a requirement for a licence to cut any quantity of cedar. To avoid the high licence fees, cutters, like squatters, kept as far ahead of the law as possible and quickly cut out the more accessible areas around Sydney. Next, they entered the extensive rainforest areas in more isolated areas, targeting trees close to the water for easy transport, working the rivers east of the Great Divide one by one heading north: the Manning, Hastings, Macleay, and the Clarence by 1835.

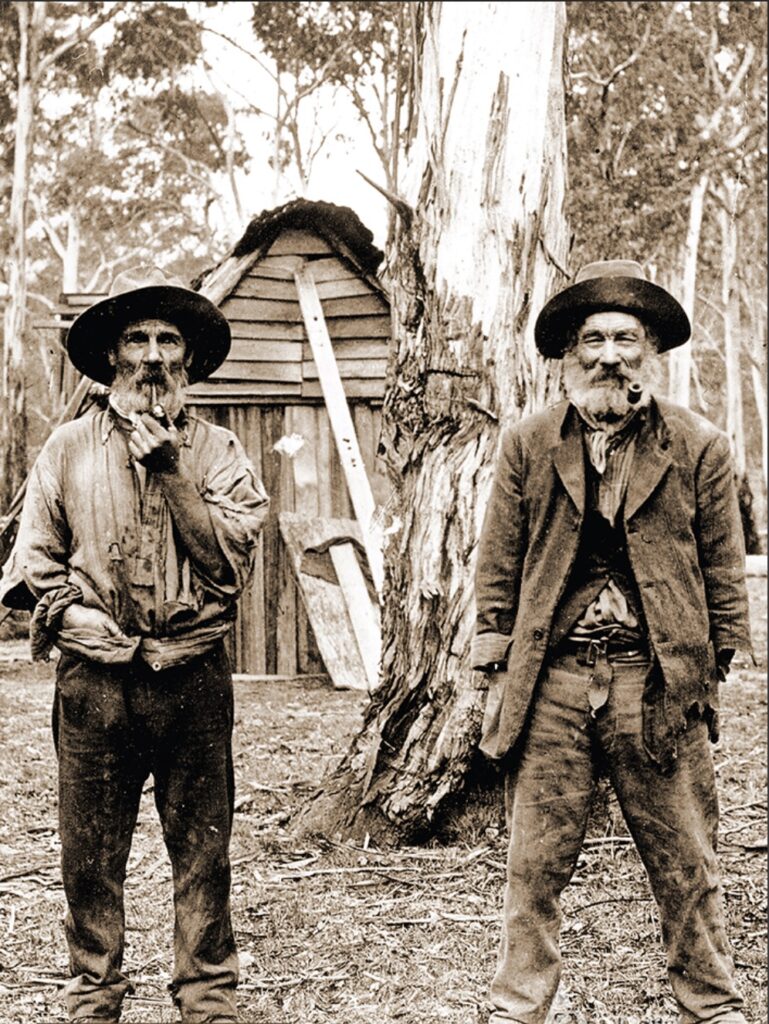

(Right) Cedar cutters. Photo Forestry Corporation NSW.

One of the best-known sources of red cedar was the large area of rainforest north of the Richmond River, between Lismore, Ballina and Cape Byron, known as the Big Scrub. The cedar cutters sent their first cargo of timber from the Richmond River to Sydney in 1842. They opened the way for European settlement in the Richmond Valley and northern coastal areas. The farmers followed them, clearing, burning and opening the valley floors.

Higher in the catchments, the cedar cutters levered the logs into the water and had to wait for a flood to float cedar logs downstream to the main rivers, followed by men on a boat with long poles to guide them to Casino. It was here where a heavy two-ton chain across the Richmond River collected the logs. It held up to 400 logs this way. The logs were then claimed by their owners and floated to depots at Irvington and Coraki as immense rafts of logs tied together to wait for ships. Schooners then took them to the Sydney market.

During the three years from 1842, official figures estimate that cutters sent 800,000 super feet (or approximately 1,900 cubic metres) of cedar to Sydney each year. However, by 1870, supply had dwindled remarkably, and little of the remaining accessible cedar resource remained.

Long Creek in the 1930s. Photo Forestry Corporation NSW.

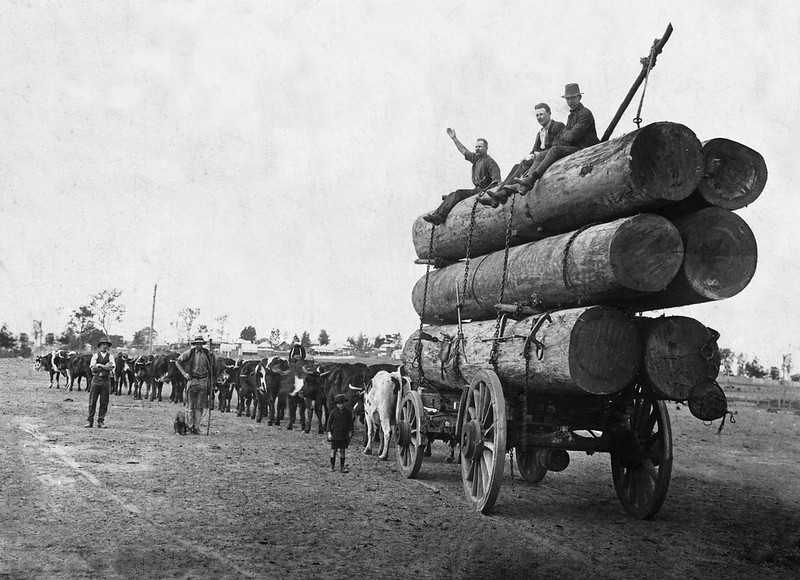

Around 135 bullock teams were transporting the logs out of the bush to the sawmills and the railhead. The railway from Casino to Kyogle accelerated the growth of the timber industry. Eight mills were operated in the Upper Richmond Valley at the time.

In those days, sawmills were in the more remote mountain valleys close to the timber resource. It was here that small villages grew around the mill.

One example is Long Creek, where Munro and Lever built houses for their sawmill workers, and the settlement also had a small school, grocery shop and tennis courts.

Rainforest harvesting

The clearing of rainforests quickly followed the initial red cedar operations to provide agricultural land through the 1920s. It was particularly the case in areas on the valley floors, and it occurred substantially in the Richmond-Tweed Valleys in the Big Scrub and further south on the Dorrigo Plateau. It caused the loss of substantial areas of the rainforest in NSW.

After 1900, when the availability of red cedar diminished, the rainforest timber industry shifted its focus to cutting hoop pine. In 1918, Munro and Lever opened a veneer factory at Terrace Creek, near Kyogle to produce plywood mainly from hoop pine. The plywood was used as flat sheets in buildings and furniture. However, the veneer was also moulded for aeroplane wings, boats and canoes, and motor vehicle bodywork.

Bullock wagon with hoop pine logs sent to Bennett Bros sawmill at South Casino, 1917. Photo Forestry Corporation NSW.

The stands of hoop pine must have been enormous. A report in 1910 noted it had been depleted on the lower Richmond, although:

“…on the rangiest the head of the Richmond…there is a vast supply, which one would think inexhaustible“.

Stands of hoop pine were found in dry rainforest on steep slopes just below the sub-tropical and warm temperate rainforests on the basalt plateaus. The Munro and Lever mills at Grevillea and Kyogle, and Long Creek further north cut around 186 million super feet (439,000 cubic metres) of hoop pine continuously for 32 years between 1912 and 1943.

Records reveal that the hoop pine harvested between 1912-1958 was just over 288 million super feet (680,000 cubic metres).

While hoop pine was predominantly used in building and cabinetmaking, it was soon used for butter boxes as dairying was the primary agricultural activity in the area. Initially, there was a fear that the pine would taint the butter, but after Munro and Lever obtained a contract for hoop pine butter boxes in 1914, they soon found that the fear was groundless. The Kyogle Examiner in 1912 reported that:

“New Koreelah is the only place in New South Wales where tasteless pine suitable for butter production can be obtained”.

The millers gradually utilised other species once they appreciated their unique properties. They included white beech (Gmelina leichhardtii), rosewood, crows ash (Flindersia australis) and coachwood (Ceratopetalum apetalum). However, hoop pine remained the dominant species, representing 80 per cent of the total cut.

Early forest conservation & management

Clearing of land for agriculture and the ringbarking of trees for grazing led to the greatest waste of timber on a scale that surpassed the amount used in the timber industry. It led to a rapid decline in the rainforest resource.

Today, the terms foresters and conservation are never mentioned in the same breath. Yet, the persistent efforts of early forest surveyors and foresters protected forests and timber from clearing.

Rather than blockading farming activities, making personal threats against farmers, or even participating in political blackmail, so common in forest protests since the 1970s, the early foresters focused on background persuasion and representations to their political masters.

The principal aim was to reserve forestry land from settlement rather than regulate the harvest from it. The first reserves were designated in 1871:

“…to protect some of the magnificent forests of brush and hardwood in the Clarence Pastoral Districts”.

In 1875, the first forest ranger was appointed to the Occupation of Lands Branch within the Lands Department. His task was to administer the regulations under the various Lands Acts relating to reserves. The following year, with the establishment of the first Forestry Branch, timbered land was set aside for possible future timber production. These timber reserves reached 4.7 million acres. Licencing was introduced to regulate and control the timber getters’ activities and implement minimum tree size cutting and royalties.

The Forestry Branch was attached to many departments during its life. These included the Department of Lands, the Department of Mines and the Colonial Secretary until the establishment of its own department in 1890. However, the new Forestry Department was soon amalgamated with the Department of Agriculture in 1893, only to see the Forestry Branch re-established and transferred back to the Department of Lands in 1896.

Timber reserves weren’t a secure form of tenure as they could easily be revoked for settlement and clearing purposes. So, forest officers started a campaign to protect forests from alienation permanently. It involved the removal of forest administration from the control of the Department of Lands, whose primary function was to promote the settlement of the Crown lands.

There was still alarm at the disappearance of forests but also growing concerns over an impending shortage of timber, and these issues led to a Royal Commission of Inquiry in 1907. As a result, the Forestry Act 1909 re-established a Forestry Department with a Director of Forests and forestry officers. One of the provisions of the Act was a requirement to classify the remaining forest lands and decide which should be permanently dedicated as state forests and which should remain temporarily protected as timber reserves. State forests soon became the basis of forest policy in the state. By December 1913, forest officers recommended an area of about 3.4 million acres for proclamation as state forests, but the Department of Lands agreed only to dedicate 53,117 acres.

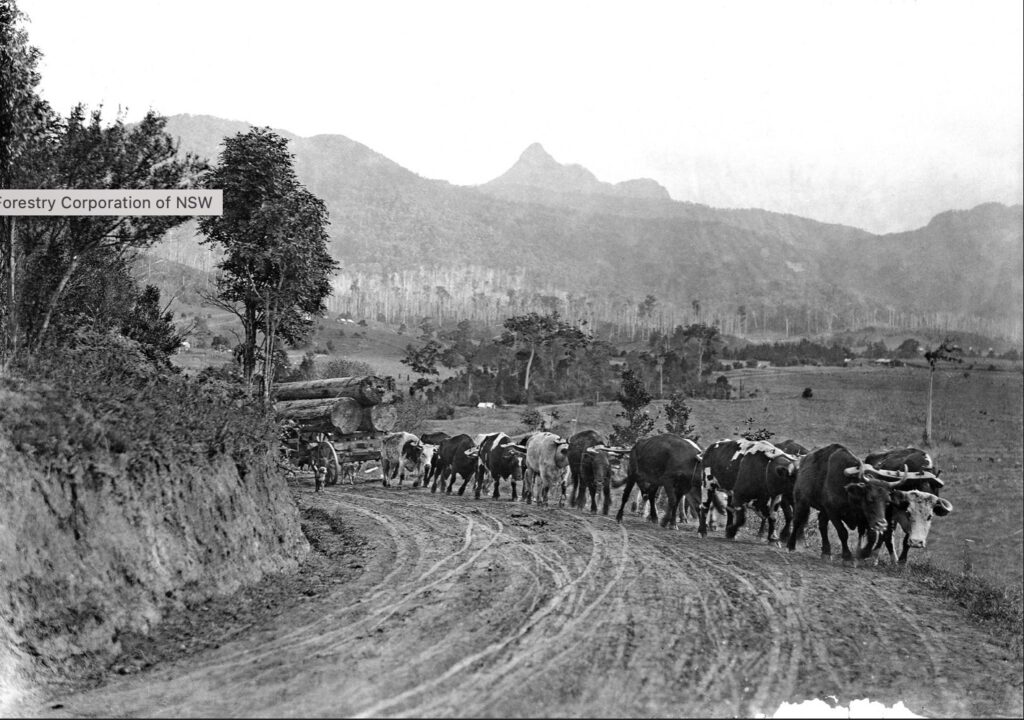

Hauling cedar logs up Mount Ash with Mount Warning in the background, 1920. Photo Forestry Corporation NSW.

A new Forestry Act 1916 abolished the Forestry Department and created a Forestry Commission (FCNSW). Richard Dalrymple Hay, the first Director of Forests under the previous Forestry Department, was appointed as the inaugural Chief Commissioner. The new act required the reservation of not less than five million acres of state forest within three years.

The first state forests were Acacia Creek and Koreelah State Forest No 1 and Mandle and Beaury State Forest No 2, both situated adjacent to the Queensland border in the northern portion of the Clarence catchment. Not long after, the government soon proclaimed another 45 state forests comprising 320,000 acres.

The hardwood forests on the north coast had rudimentary management plans drawn up, and a cut was prescribed based on a rough assessment of the growing stock. Commissioner Norman Jolly was able to report in 1927 that:

“…the area worked through for regeneration during the last ten years has now embraced the greater part of the valuable and accessible forests which had been subjected to excessive exploitation during the preceding generation”.

However, there were a few issues which made overall management difficult. For example, the prescribed yield was calculated to match the mill capacity rather than the capacity of the forest to grow trees. There was also a lack of trained staff to supervise operations; thus, a single tree selection was the norm. Another major problem was wildfire’s effects, wiping out any regeneration and consequently creating a poor distribution of age classes.

It wasn’t until after WWII that the management of the forests improved, but it came with the competing issue of a very high demand for timber. This factor alone had long-lasting implications for the forests, particularly the rainforests.

Consequences of the WWII war effort and post-war economic boom

Despite a severe reduction in housing activity in the early periods of the war, which affected the profitability of the timber industry, the declaration of war with Japan at the end of 1941 created a considerable upsurge in timber demand for military purposes. As structures were needed quickly and were expected to be temporary, the need for milled timber snowballed. As a result, closed mills reopened, and others worked long hours adding shifts.

The massive demand for timber is not appreciated or recognised in discussions about forest utilisation. It was also compounded by the need to find substitutes for imports, which constituted nearly a third of domestic consumption before the war. Consequently, the war placed heavy demands on state forests, particularly the rainforests in NSW and Queensland.

Rainforests played a pivotal role in Australia’s performance on the battlefields, our defence against an invasion by the Japanese and the country’s recovery after the war. The Federal Government placed restrictions on using hoop pine and coachwood to utilise them solely for war purposes. Timber was harvested hastily without any silvicultural considerations under the direction of the Federal Government’s wartime “Timber Controller”, bypassing the state government regulatory agencies.

Foresters didn’t complain as they saw this expediency as a patriotic duty and the timber industry’s contribution to the war effort. Coachwood, in particular, was in strong demand for rifle stock and butts and cut into plywood to frame the Mosquito fighter-bombers.

The demand for timber continued at very high levels after the war. There was a surge in home construction right across the country. While foresters successfully resisted pressure after WWI to allow timber reserves to be cleared for soldier settlement farming, they couldn’t limit timber cutting to sustainable levels after WWII.

By the mid-1950s, timber production was higher than during the war years. Over 271 million super feet (640,000 cubic metres) were cut prior to WWII in 1938-39 and rose to 516 million super feet (1.2 million cubic metres) immediately after the war. Production reached a peak of 610 million super feet (1.4 million cubic metres) in 1951-2. It also coincided with the arrival of the mechanisation of logging methods. The chainsaw, bulldozer and timber jinker replaced the axe, crosscut saw and bullock teams.

The high level of cut was partly offset by a greater area made available for logging by opening some of the mountainous foothill forests. In addition, from 1947, FCNSW was able to extend access into areas outside the original supply zones through a notable increase in the selling price of native timbers.

Cost pressures and industry changes

By 1951, the timber industry faced rising costs due to increased rail and freight charges and basic wages. They demanded a reduction in royalties charges. At the same time, FCNSW wanted to increase royalties to offset increases in their costs. They increased royalties amidst a resentful industry, and the FCNSW managed to achieve “budget equilibrium” through loan funds. But the government reduced the loan allocation after the first year, and “budget equilibrium” was only achieved via a reduction in essential maintenance and capital works.

As costs rose with general post-war inflation and revenue was affected by the vagaries of weather and major bushfires, particularly during the severe 1951-2 summer fire season, the concept of “budget equilibrium” was abandoned. Instead, the government resumed responsibility for filling the gaps at the end of the financial year between revenues and earnings.

Before the war, FCNSW had already confirmed in its legislation that 50 per cent of royalties, its primary source of revenue, would be retained for expenditure in the next financial year. The other 50 per cent provided a contribution to essential public works for the state such as schools, hospitals and roads. This is a critical aspect often ignored when claiming forestry was continually subsidised.

In 1953, FCNSW introduced an allocation of log quotas measured by volume from areas they nominated to replace the original area allocation system. This allowed FCNSW to gain more control of the exploitation of the forests. Foresters now had more flexibility in selecting areas to log. They also introduced more stringent harvesting control by tree marking rather than allowing the faller to nominate which trees to be felled.

Meanwhile, things began to unravel when the Commonwealth government abolished import licences in the 1960s. Importers seized the opportunity to import larger quantities of timber from North America on short-term credit at high-interest rates. But when the Commonwealth government introduced a credit squeeze in the late 1960s, it soon led to a downturn in the building industry. The imported timber was disposed of cheaply, which led to a significant slump and rationalisation in the sawmilling industry.

The major sawmills of the 1950s and 60s were Munro and Lever at Grevillea, Lance Sly at Woodenbong, Fraser Brothers at Wiangaree, the Rosebery sawmill, and the Veneer Company at Kyogle. But the forced industry rationalisation during the 1960s saw the closure of the Fraser Brothers mill in 1961 and the Rosebery mill in 1967. Amalgamations occurred in other mills. Lance Sly became Ford Timbers, and the Veneer Company at Kyogle moved to Grevillea.

For FCNSW, the level of cut was still profoundly concerning. Between 1935-47, they attempted to cut yields so that tree growth and removal were in balance, but these were usually successfully resisted. In the post-war period 1947-53, powerful segments of the timber industry were able to exact concessions which meant that they could still cut wood in some areas faster than it was growing.

Another problem was the limited silvicultural practices after logging because of the lack of funds redirected to the establishment of exotic pine forests in the south of the state. It led to the airing of frustrations in annual reports. For example, the Kyogle forester wrote in 1959/60:

“The pressure by sawmillers for an increase in log quotas…must continue to increase, and the absolute lack of management plans for any hardwood forests for the district makes it in no way easy to restrict the rate of cutting to a figure commensurate with the ability of the district to supply in perpetuity.

Foresters always thought that once demand dropped and pressures eased, they would have the opportunity to reduce harvesting levels, take stock and refine silvicultural practices, ensuring a crop of trees to meet future timber demands. During the 1950s, this was increasingly difficult for political reasons.

At the NSW Timber Inquiry, set up in 1965, in part to look at the availability of the resource at the time and the future timber needs of the state, it finally became apparent that the concerns foresters on the north coast had been expressing for several years were indeed true. The most significant source of angst was the inability to treat all areas needing treatment after logging. One forester summed it up:

“We were battling for money all the time. There were things that we thought we should have been doing, we know we should have been doing, but we weren’t getting the funds to do it”.

Yield regulation in the early 1970s, aided by computerisation, became strictly controlled and political pressure to make more wood available was declined.

In 1976, FCNSW released its Indigenous Forest Policy which, although written with the whole state in mind to introduce the concept of multiple-use management, was inspired by a need to “clarify” the situation for forest management in the highly productive north coast region. It said in part:

“The more mountainous and less accessible forests behind the coastal plain should be logged for sawlogs to the limit of economic accessibility … Regeneration should be obtained by natural methods, generally without the assistance of any silvicultural treatment”.

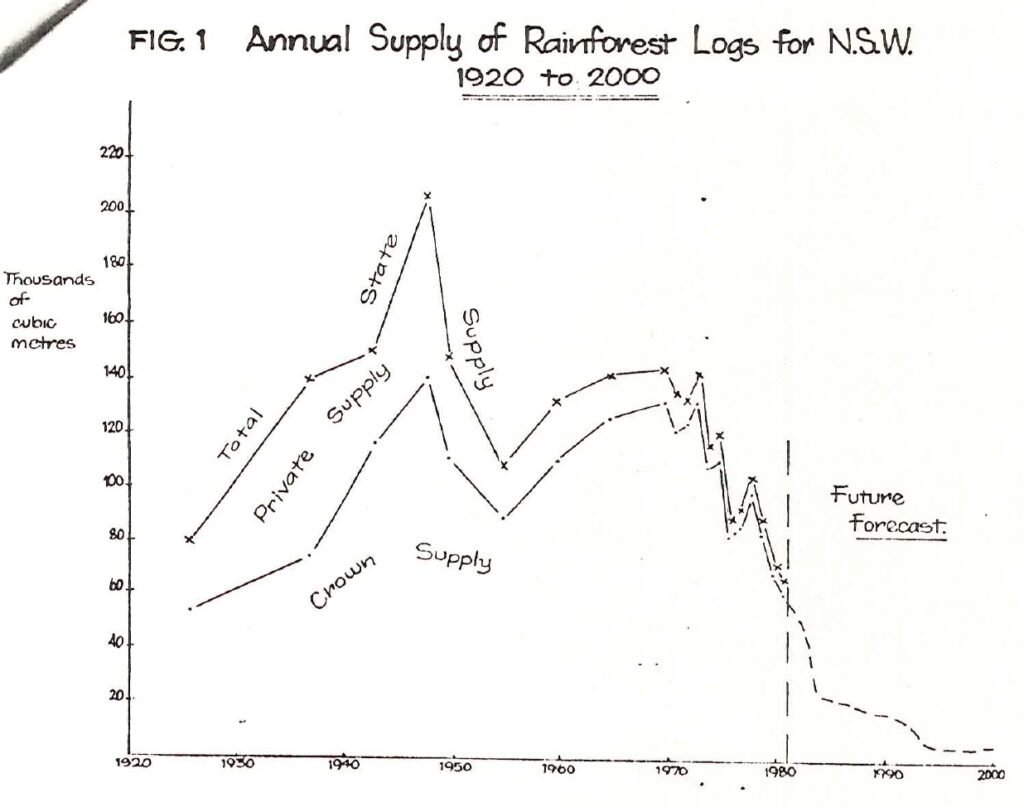

The policy also confirmed FCNSW’s intention to phase out rainforest logging subject to existing commitments. During this period, conservationists and the media unfairly accused the FCNSW of only focusing on the pure economics of forestry and ignoring the social impact. However, to please their political masters, FCNSW had to find ways to soften the inevitable decline of rainforest milling.

Improved management of rainforests

When the alternative residents moved into the Richmond and Tweed Valleys and started raising questions about the active management of rainforests, foresters had been grappling with the same question much earlier.

Up until the 1930s, previously logged rainforest stands were alienated and cleared. Where alienation wasn’t happening due to protection as timber reserve status, very light logging had occurred because of the selective markets at the time. Unfortunately, without any silvicultural knowledge, the stands were left without post-logging treatment as there was little expectation that they would support a cut in the future.

Such areas were an invitation for further claims to have them converted to agricultural use. It prompted FCNSW to begin a program around 1937 to plant the native rainforest conifer, hoop pine. This in part was prompted by local farmer agitation to have the cut over rainforest on Acacia Plateau at Koreelah State Forest thrown open for settlement. Nurseries were established and rainforest areas cleared, with the first plantings in 1938. Other areas at Toonumbar, Mt Pikapene and Mebbin were brought into this program. Between 1938 and 1954, about 1,500 hectares of plantations of hoop pine and the related bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii) were established on cut-over rainforest sites in northern NSW. However, the program stopped because costs finally became prohibitive.

As well as logging the rainforests, foresters also reserved worthy areas which they did without any fanfare or recognition. They set aside several rainforest reserves in the late 1930s. They were Tooloom Scrub near Urbenville, Allyn River near the Barrington Tops and Bruxner Park near Coffs Harbour. By 1982, although rainforests made up only about four per cent of the area of state forest in NSW, over 50 per cent of the 152 areas preserved in state forests contained significant rainforest stands.

The late 1930s also saw a research program commence into the silviculture of the primary rainforest commercial species. By the time the hoop pine planting ended, there was accumulating evidence from the studies that the rainforest stands could be managed for sustained timber production. A North Coast Silvicultural Research unit was set up at Coffs Harbour in 1951 which began to examine the silvicultural capabilities of rainforests stands objectively under various field experiments.

For example, field plots showed that the regeneration of representative species was plentiful in sub-tropical and warm temperate rainforests. Still, in the more heavily logged stands, they were usually overtaken by fast-growing pioneer species of small trees and vines. There was an accentuation of crown dieback in many of the remaining trees associated with heavy logging in the coachwood stands, which did lead to a period of clearfelling and planting eucalypts after logging. It also enhanced the myth that rainforests in New South Wales could not be managed for continued timber production. But overall, the plots found selective logging operations retained the general appearance and structure of the rainforest, unlike more intensive operations, where the forest structure was altered for a lengthy period.

Many rainforest species failed to grow satisfactorily as potential timber-producing trees when planted in open plantations, except hoop pine. However, provided they were not overwhelmed by weed growth and vines, enrichment plantings in small openings in the rainforest served as a valuable means of maintaining stocking.

Foresters tried to apply the results of this continuing research to the rainforest stands. Management of the rainforests, as opposed to conversion to either farmland or plantation, was instituted in late 1956, when a provisional research working plan was introduced. In about 1960, FCNSW silviculturalist George Baur introduced a new policy of “50 per cent canopy retention” in the Casino Region, with techniques refined as more experience was gained. Further south, in the warm temperate coachwood stands around Dorrigo, foresters managed the intensity of logging under a light selection system, which was problematic as it made operations economically unviable and yielded too little timber to maintain existing industries.

But as in most cases in the real world, the best-laid plans can often be challenging to apply to get the optimum results. Unfortunately, over time, the 50 per cent canopy retention become a political solution, not a silvicultural one. A very conservative approach crept in as too many younger growing trees were cut down to leave the big old trees to achieve the retention target.

The photo to the left shows a log dump at Terania Creek, surrounded by forest that has been harvested. It hasn’t opened up the canopy sufficiently to aid in regeneration and this was a widespread problem wherever the new policy was implemented.

(Left) This aerial shot shows log dump at Terania Creek. The surrounding area was harvesting under the 50% canopy retention system, but you wouldn’t know it.

As alluded to earlier, the major problem in virtually all areas was the commitments given by governments to supply rainforest timber at higher levels than the forests could support. These commitments derived either from the performance of sawmills in the immediate post-war years or, in a few notable instances, from a government desire to establish economically viable decentralised industries, usually centred around veneer plants.

The commitment of timber harvesting levels in the two main rainforest logging areas – the Richmond-Tweed and Hastings Valleys – was in the order of at least three times the likely sustainable yield. However, the real dilemma for foresters was that as time progressed, the opportunity to introduce sustained yield harvesting became less and less attainable as the area of remaining unlogged rainforest diminished. It became a much less important imperative in the rainforest stands as foresters made plans to phase out rainforest harvesting.

Nonetheless, considerable progress was made by FCNSW in the 1970s to reduce rainforest commitments and lower the annual cut. The intention was to avoid a sudden cessation of rainforest logging, since this could only result in widespread industry disruption, unemployment and severe social stress, something politicians would not countenance.

The stark reality was that not long after the ability to support a perpetual rainforest timber industry in the short to medium term disappeared, along came people who began to take a very active interest in the logging operations in the Tweed-Richmond Valleys. It was a great irony to a forester, who had already set in train the eventual end of brushwood allocations from rainforests, that a perfect storm arrived that left them in the crosshairs.

Next week’s Part 2 will examine the conflicts that arose over utilising rainforest and hardwood timbers in general in the north coast and hinterland forests, with a focus on the Border Ranges dispute.

Hi Robert, thanks for pulling that together- an interesting read. I suggest you check the super feet to m3 conversion in the calculations of harvest levels. My quick google search has it at 0.00236m3 and this generates numbers that look more reasonable.

Thanks Duncan. That conversion factor is familiar. I am not sure why I used those figures as I can’t recall doing the conversions, but obviously I wasn’t thinking it through when I made the calculations.

I have made the necessary changes.

You were probably right the first time Robert.

Up until the 1970s timber volumes (in the round) were normally given in super-feet Hoppus. One cubic metre (true) is 332.833 su.f (Hoppus). Sawn timber would be measured in board-feet, or super feet (true). A simple geometric conversion gives one cubic metre equal to 423.776 su.f (true).

The Hoppus (or ‘quarter girth’) method estimates volume as being the square of one quarter of the centre girth of the log (in inches) multiplied by one twelfth of the length in feet. For a perfectly cylindrical or truncated paraboloid log, the Hoppus estimate will be exactly pi/4 times the true geometric volume.