It seems that the people who came up with the plan to return all Western Australia’s and Victoria’s public land to a cycle of lockup and incinerate wilderness management know as much about forest management and timber supply timelines as an average kindergarten pupil. – Quote from South East Timber Association

When I started as a young forester in the late 1980s, I yearned for the opportunity to work in our native forests.

While assessing a coupe to plan for a tree harvesting operation, I knew I was inheriting a forest structure that benefited from silvicultural practices adopted by foresters a few generations before me. Foresters aim to make the forest more productive by applying scientific principles to aid in the regeneration of the next crop of trees and to encourage the best growth of the retained trees. My responsibility was to continue that tradition for foresters a few generations ahead of me.

However, working on the north coast of New South Wales at the time was challenging, particularly in a valley where many alternative lifestylers and hippies had converged since the late 1970s. Increased political pressures forced foresters to compromise on their silvicultural principles in favour of perceived environmental benefits.

We had to endure the calls to save the forests from the chainsaw to protect the animals. Yet, few people appreciated that the animals that were supposed to be disappearing were still in the forest in healthy numbers despite numerous cutting cycles involving deliberate ground disturbance and burning. I knew this because I carried out several nocturnal spotlighting surveys and played owl calls in areas before harvesting.

A great example was an area of Pine Creek State Forest that had been logged at least seven times since the 1880s. It was adjacent to ex-cleared farmland purchased by the Forestry Commission in the late 1930s and was reforested. In the past, it also supported a settlement of houses and a school, banana plantations and a couple of sawmills. I found healthy populations of koalas, greater gliders and yellow-belied gliders in the forest. Powerful and masked owls responded to the taped calls. The area is now a national park, and it would be interesting to find out if the forest is still as healthy as it once was.

There are many examples around the country where state forests support diverse vegetation communities, healthy populations of rare and endangered species, and low fuel loads compared to nearby overgrown, weed-infested and poorly managed reserves.

However, this reality mattered little in the cut and thrust of politics. Throughout the 1990s, New South Wales Premier Carr transferred millions of hectares of actively managed state forests to reserves under a management regime of benign neglect. As bureaucratic restrictions increased on the remaining areas available for harvesting, I realised native forest harvesting was slowly dying by a thousand cuts.

Managing a forest area for its range of values, including timber, wildlife, water catchment, etc., became increasingly difficult without achieving an optimal result. Senior managers had lost the appetite to allow us to carry out post-logging burns in wet forests to ensure regeneration because of the intense scrutiny. Things were getting out of balance. We were losing the ability and the priority to practice proper forest management. Instead, we had to focus on the short-term goal of ensuring that the sawmills continued to get supplies while unquestioningly adopting environmental prescriptions that did little to improve the ecology of the forests.

When I managed the Taree District in the mid-1990s, I still remember a logging contractor floating his machinery to the next coupe. The machinery was only suitable for harvesting in the mature foothill forests. After activists pressured the environment minister to stop the proposed harvesting, I had to redirect him to the younger regrowth forests on the coast.

The contractor’s business was not allowed to go down the gurgler, nor were we to disrupt the timber supply to the sawmill, even though the logs were much smaller than usual, just to protect the minister’s arse from any industry furore through the media. It led to the destruction of future timber resources in part of the forest because I didn’t and couldn’t stand up to this folly.

I moved on to north-west Tasmania and enjoyed a planning framework that supported good silvicultural practices. However, I still worried about what would happen in New South Wales as more areas were locked up from harvesting and more environmental controls were added.

I felt I had been a part of the beginning of the end. I kept asking myself what the purpose of utilising forest areas was to produce timber products to meet the public’s needs if we could not leave the forests more productive.

Fast forward to the start of 2024, and part of my fears came to pass as the confirmed cessation of native forest logging in Western Australia and Victoria became a reality. New South Wales continues to harvest its native forests, but for how long? Which state will be next?

Victorian ban on native forest harvesting

The right to govern is a privilege and it must never be taken for granted. Governments must also be honest and transparent. Respect for the Victorian people starts with respect for our democracy – Victorian Labor Party’s 2014 election document.

On 7 October 2019, the then-Agriculture Minister Jaclyn Symes wrote to Corryong sawmiller Graham Walker to reassure him that his mill and workers had a future after he expressed concerns. She wrote:

It is the Victorian Government’s view that the careful management of Victoria’s State Forest can support the sustainable supply of resources as well as the protection of biodiversity.

A month later, Premier Daniel Andrews announced the industry was not sustainable and that all native forest logging would end by 2030, stunning not only Walker and his employees but also the 2,500 timber industry workers around the state.

After repeated requests, Andrews refused to release the science and information which proved his assertion that harvesting native forests was unsustainable. Symes claimed:

The government’s decision was informed by wide-ranging consultation and assessment.

She lied as the industry received no such consultation. Nor did she provide any indication of the science behind the decision.

But what is worse, Freedom of Information (FOI) documents reveal a two-page briefing paper titled Native Forestry Industry Transition Approach, was signed off by Andrews on 9 April 2018, favouring the option of exiting native forest harvesting by 2030.

A handwritten note said, “Negotiations should be expedited – not delayed”. However, Andrews waited 12 months after the 2018 state election to go public. He misled the public by not disclosing his decision before the election. He and his Ministers, including Symes, treated the forestry sector as fools despite the government backtracking by arguing:

The March 2018 brief did not recommend the adoption of a policy by the Victorian Government.

Despite all this secrecy and obfuscation in the name of politics, a spokesperson for the premier lied by arguing the government consulted with the community and being as transparent as possible about their decisions was a priority, “to suggest otherwise is simply wrong”.

Andrew’s delayed decision was motivated by his fear of an electoral backlash in the Morwell electorate after the job losses associated with the closure of the Hazelwood power station. He was trying to take the seat from the former Nationals MP Russell North, who held a margin of just 1.8 per cent.

More documents released under FOI show that after the November 2018 election, the government commissioned Quantum Market Research to survey groups in marginal electorates on native forest harvesting. They bribed participants with $100 prepaid EFTPOS cards and used taxpayer funds for an online survey of 220 Melbourne residents and another 200 from other marginal seats.

The government’s response to this revelation was:

The Victorian Forestry Plan has always been about transitioning the native forest industry to a range of new opportunities by 2030 and setting up a strong plantation-based sector for decades to come.

In July 2020, the community formed a Native Timber Taskforce in response to the government’s refusal to release the science that determined the need for a phase out of logging. The taskforce lodged an FOI request seeking all documents relating to that decision without success:

The Office of the Premier undertook a thorough and diligent search for documents, however, no documents relevant to your request were identified.

The taskforce lodged complaints with the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner and sought a review of the FOI decision by the Civil and Administrative Tribunal. Three months later, they finally received 159 pages without any scientific data. The taskforce chair was not impressed:

What we did finally receive from the government was rubbish. It was a heavily redacted document that didn’t in any way answer our questions. This has been so difficult that we have no choice but to believe the government has been deliberately hindering the process in the hope that we will give up and go away.

The Mayor of Wellington Shire, Councillor Ian Bye, believes the refusal to release data that supports the government’s decision means the data doesn’t exist or the government is unwilling to share it with the communities most impacted.

Meanwhile, Victoria’s forest agency VicForests, was continually embroiled in lawfare court cases challenging the legitimacy of their operations in native forests. Activists have been allowed to get away with a loophole in the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004, which allows anyone to take legal proceedings for alleged minor breaches. It means “any half-arsed activist group with outrage” can get standing in the Victorian Supreme Court and cripple an industry. They rarely won cases, but that didn’t matter because the activists learnt they could continually stop forestry operations. They used injunctions granted in legal proceedings to make harvesting in many planned coupes unviable or prohibited altogether.

When VicForests tried to recover $2 million in court costs from one of the activist green groups, the premier told them to back off. The activists enjoyed the rare privilege of gaining protection against failure.

A surprise Federal Court ruling in May 2020 sustained the activist’s argument that VicForests were systematically breaching a precautionary principal clause in the Code of Practice and thus contravening the federal environmental legal requirements under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999. The decision was perplexing because Victorian forests were harvested under the Code of Practice for many years without any suggestion that VicForests breached the precautionary principle.

For over 15 years, the world’s largest certification scheme accredited VicForests’ practices, which required independent audits. None of the audits questioned VicForests’ compliance with that part of the Code. In addition, regular audits of VicForests’ compliance with the Code by Victoria’s Environment Department never raised any issues.

Predictably, VicForests successfully appealed the decision, but they, and forest contractors, suffered heavy financial losses in the drawn-out saga. Rather than respecting the decision, the media did their best to discredit the appeal decision and parroted the activist’s rhetoric about illegally contravening national environmental laws.

Instead of closing the door on the legal loophole, Premier Andrews announced in May 2023 plans to bring forward their decision to phase out native timber logging to end by 1 January 2024, giving workers and businesses just six months instead of seven years to find other jobs. A statement released by the government said their decision removed the uncertainty caused by ongoing court and litigations and the effects of severe bushfires in 2019-20.

Another court case in November 2022 ruled that VicForest’s pre-harvest surveys were inadequate and did not protect two glider species – the greater and yellow-belied gliders. VicForests were forced to issue stop-work orders due to the injunctions, which brought all the state’s logging activities in native forests to a halt.

VicForests appealed the decision. However, Victoria’s Supreme Court of Appeal rejected all their arguments in June 2023, upholding the initial ruling.

Losing the case was the final nail in the coffin for native timber harvesting in the state. The government remained ambivalent about the demise of a billion-dollar industry and thousands of Victorian jobs. The Treasurer’s meek summation reinforced the government’s lack of will to change the legislation to maintain the sustainable native timber industry and protect it against frivolous lawfare:

The courts have taken the decision out of our hands.

Western Australia also bans native forest harvesting

One minute, we’ve got a business worth millions; the next, we’ve got scrap metal.

In December 2019, the Western Australian Forestry Minister, Dave Kelly, praised and encouraged the investment by Parkside, a Queensland timber firm, into the state’s native forests:

This is the largest native forest industry private investment consolidation and restructure in 15 years which will secure hundreds of direct and indirect jobs in the industry.

Kelly also welcomed Parkside’s commitment to create high-value timber products from smaller, regrowth trees, arguing that the native forestry sector is:

An important employer and economic contributor that supplies our community with sustainable, renewable building materials and other timber products.

Kelly gave further confidence to the industry in a speech to Parliament in March 2020:

Parkside has come to Western Australia and made significant investments because it had confidence that this Government supports the ongoing native forest industry.

The government provided this support after 2001 when the Gallop government banned old-growth logging but still encouraged a restructuring of the native forest industry based on the regrowth resource. Many people chose to remain in the industry based on what the government told them and the public support they received.

Even though the government heavily regulated the industry, family businesses believed in their support and were happy to invest in the future. They made their decisions with the government’s encouragement and the support of the forest agency, Forest Products Commission (FPC).

Suddenly, things changed. Politics determined that the native forestry industry was on the nose and bad for the environment. This was despite two substantial independent audits in the previous ten years that found native forest utilisation was sustainable.

In September 2021, the Premier of Western Australia, Mark McGowan, made a shock announcement that all native forest logging would cease in 2024, at the end of the current 10-year Forest Management Plan. Communities accused the Premier and Kelly of delivering a “coward’s punch”. Instead of fronting up and announcing their decision on location in the timber towns among the karri trees, they chose Woorooloo on the outskirts of Perth – an area that suffered a raging bushfire earlier in February due to a lack of active management of the surrounding bushland.

Standing next to the premier was Kelly, loyally nodding as his leader announced the decision. Kelly took credit for saving the forests but went missing and refused to take credit for the impact on family businesses as he failed to attend public meetings in timber towns.

They made their decision without consultation with the timber industry, the public, government agencies or even the local member of parliament. The reasons for the decision were to save the forests and preserve the carbon stocks. The premier said they would protect two million hectares for future generations.

Kelly also argued climate change had significantly contributed to a decline in the harvest yield from the native forests.

The government’s rhetoric centred on its commitment to act on climate change and protect biodiversity by reducing deforestation and forest degradation. The Environment and Climate Action Minister, Reece Whitby said:

The science showing climate change is having, and will have, a devastating impact on our environment is well-established and cannot be ignored.

The government relied on and quoted from the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, which argued that reducing deforestation and forest degradation was the “most effective and robust way” to mitigate climate change. It was just an example of cherry-picking and clutching at straws. The government failed to admit that our native forests provide natural, biodegradable and renewable timber products. Growing trees, drawing carbon from the atmosphere, and converting it into environmentally friendly, carbon-storing products that can be repeated is a positive for the environment. Well-managed sustainable forests help the planet. The IPCC agrees:

In the long term, a sustainable forest management strategy aimed at maintaining or increasing forest carbon stocks, while producing an annual sustained yield of timber, fibre or energy from the forest, will generate the largest sustained mitigation benefit.

As documents released under an FOI request reveal, foresters were alarmed at the lack of evidence-based analysis behind the government’s decision. The Chair of the Western Australian Branch of Forestry Australia, the body representing professional foresters, Brad Barr, said the decision to end native forest timber harvesting without any scientific backing raised questions about the government’s true motives.

“Claims by the Western Australian Government that climate change and declining rainfall make future harvesting of native forests unsustainable have not been backed by evidence … It seems that the Government tells us to ‘listen to the science’, except when the science contradicts its own policy objectives”

It has become apparent that the government wants to end native forest logging forever, even if scientific evidence shows the harvesting of native forests is sustainable. Whitby made this clear to the public. At the same time, he had to concede to parliament that the government based its decision on “common knowledge”, not science.

The impacts on the Victorian economy and rural communities

Dan Andrew’s decision has devastating flow-on effects in small regional communities with limited alternative employment opportunities, a low chance of re-skilling, and where 35 per cent of timber workers are the sole income earner for their household.

The Wellington and East Gippsland Councils released a report which estimated their municipalities would lose 1,110 jobs once native forest logging ended.

There are 7.64 million hectares of native forest in Victoria, and only 6 per cent is available for harvesting. About 3,000 hectares are harvested annually, 0.04 per cent of the total forest area.

Forestry contractor Brett Robin fought the Bunyip fires in his bulldozer. It was on a weekend of extreme fire danger in March 2019. The fires destroyed 29 houses, and it was estimated that 5,000 greater gliders were incinerated. When a Forest Fire Management Victoria dozer was trapped on the fire line, Robin, with two others, risked their lives to drive through the flames and rescue the trapped operator. Meanwhile, forest activists had tied themselves to machinery as part of a protest, thus preventing them from being deployed to the fire. The activists finally agreed to release the machinery if they were not arrested. By that stage, a fire in Melbourne’s water catchment blazed through the forest, incinerating around 200 leadbeater’s possums.

As the government rewarded the activists for that carnage, Robin’s only reward was losing his job.

The Australian paper mill in Maryvale, owned by Opal, produced its last ream of white paper in January 2023, following the decision to stop native forest logging. They shed more than 150 jobs. Now, Australia imports all its photocopying paper.

In September 2023, Opal announced that it could not find a buyer for its stationery business and would cease production from the end of that year.

Graham Walker announced that he would close his sawmill in September 2023 after the government gave him just 15 days to participate in the opt-out scheme and forfeit his 2024 sawlog licence. He accepted the government’s offer to ensure he could offer an adequate redundancy to his 21 employees. He knew he couldn’t continue without a guarantee of supply of sawlogs. Through persistent lawfare, VicForests could only guarantee 55 per cent of Walker’s 19,000 cubic metre allocation over the last several years.

Walker believes the government is ripping small communities apart. Three generations in his family, over 87 years, operated the sawmill. It provided nearly $5 million per year to the small Corryong community, which supported other businesses.

Similar madness in Western Australia

Consumers, builders and manufacturers are forced to rely on imported products or carbon-intensive and non-renewable construction materials without utilising our timber resources.

Foresters are puzzled as to why sustainable harvesting of native forests must give way. Yet, the broad-scale clearing of thousands of hectares of jarrah forest for bauxite mining can continue and expand in the state. The aluminium industry, the beneficiary of bauxite mining, is one of the largest emitters of carbon dioxide.

The native forest industry is critical in the fight against climate change, providing a climate solution. The industry improves forest health by actively managing the forests. The 2021 National Inventory Report, which tracks land use changes across the country, reinforces this by showing forests managed for harvesting are a net sink of 13.7 per cent of Australia’s carbon dioxide emissions.

The Australian Government’s 2018 State of the Forest Report showed over the period 2001-16, native forests subject to harvesting practices added 93 million tonnes of carbon to the carbon forest accounts. Growing forests for wood products subject to harvesting and regeneration have the highest carbon sequestration rate compared to forests without any harvesting. This rate decreases in mature and older forests as growth slows and trees begin to decay and die.

For example, studies show that Victorian ash forests conserve 300 tonnes of carbon per hectare when sustainably harvested.

This reality proves McGowan’s decision is pointless. Over half of the south-west forests are already in permanent reserves, and only a tiny proportion of the forests are harvested and regenerated each year – 5,846 hectares in 2019, or 0.2 per cent of the total forest area. On a landscape level, the cessation of harvesting won’t improve biodiversity. There will be no significant difference in the carbon stored; in fact, the decision may result in less carbon stored in wood products.

The harvesting of native forests has never been an environmental issue at the scale activists argue. No evidence exists that any species have been lost after 150 years of timber utilisation. The 2019 mid-term independent review of the Forest Management Plan did not identify any significant issues with harvesting operations.

Yet, over a million hectares of jarrah, karri and wandoo forests are already reserved in the state’s south-west. The green activists and the government must not be confident that the management of these reserves is sufficient to protect biodiversity. The government continues to ignore that the management of the state’s millions of hectares of reserves suffers from a lack of a reporting framework for trends in biodiversity and management effectiveness, which creates a barrier to evidence and science-based management.

In a previous blog, I expressed this view for reserves across the country and provided specific examples of species declining in reserves.

The false promises and compensation packages

The Western Australian government has betrayed timber businesses employing hundreds of workers, encouraging them to make significant investments in an industry they publicly supported. Now, dreams are dashed, businesses closed, and communities have been ripped apart.

The government announced $350 million to expand Western Australia’s softwood timber plantations to create and support sustainable jobs in the south-west of the state. The government stated the “record” investment would lead to an additional 33,000 hectares of plantations. Somehow, the government mistakenly thinks that softwood plantation timbers will substitute the attributes of hardwood timbers, and this only hides the real-life impact of their decision. They also think carbon is fussy about what sort of timber it chooses to get stored in. The government claims softwood plantations:

Significantly contribute to the capture and storage of carbon, assisting in the state’s response to climate change.

However, the reality is that growing pine plantations in Western Australia is not economical. Economic analyses have shown that the only value in the proposition is from land value appreciation and none from timber. The government knew this after maritime pine plantations north of Perth were clearfelled and not replanted due to government dithering and knowing it was not economical to do so. In addition, about 10,000 hectares of existing plantations have been lost to fire in the last decade and 2,000 hectares to drought.

The government boasts of the critical role softwood plantations will provide to the construction industry. But it is simply a word salad. They will have to find pristine farmland and clear vegetated areas to accommodate the new plantings, not to mention the time it will take to grow into commercial sizes.

In December 2022, the government announced they purchased just 3,000 hectares of land worth $6.2 million for pine plantations.

There was also an $80 million investment to support workers, businesses, and communities transitioning out of native logging. They have called it a “Just Transition Plan”. However, it is more a dead-end than a transition.

The government did not carry out any economic and social impact study before ending logging in the native forests. Therefore, the government does not know the impact of its decision on regional or state economies despite all the resources available within the public service.

The closure of the timber industry has left a trail of job losses. Parkside Timber decided its sawmills were no longer viable and closed them at Nannup and Greenbushes and their multi-million-dollar dry mill at Manjimup, leading to over 100 job losses. All Agriculture, Food and Forestry Minister Jackie Jarvis could add was she was “hopeful” that former mill employees would find other work.

Forced to get serious about the impact of their decision, the government tried to “salve industry wounds” by announcing $10 million for industry development grants to attract new industries and expand existing businesses. Each applicant could apply for up to $2 million. However, the lack of confidence in government support within business circles is palpable. The risk of working with this government is seen as too great. Existing timber industry businesses cannot continue without a resource, so their alternate investments would have to be in non-resource opportunities such as tourism, agriculture, and services.

Meanwhile, as the government continually reneges on deals for affected timber industry businesses and workers, leaving many in the dark and their survival uncertain, the newly announced environmental initiatives for the south-west region, including a $750 million Climate Action Fund, must be underwritten by royalties from the mining of finite iron ore resources in the Pilbara. The perverse irony is lost on the beneficiaries of this extravagance.

The government told the industry this wasn’t the end for them. The new 10-year Forest Management Plan will allow salvage operations associated with bauxite mining and ecological thinning in native forests. However, only two months after native forest logging ended, contractors still idly wait for the government to honour their promise. The government has no plans, nothing is published, and no one can answer the industry’s enquiries. Instead, taxpayers foot the bill to compensate the contractors doing nothing as they patiently wait to see if they still have work in the industry.

In Victoria, after the government announced an accelerated plan to end native forest harvesting, an additional $200 million was promised on top of $875 million allocated towards a transition to rely on plantation timber.

Community and industry pressure forced the government to announce changes to the Victorian Forestry Worker Support Program. They increased worker top-up payments, but they lacked any specific details. The compensation also failed to support sawmill owners who invested lots of money in new facilities they believed would continue until at least 2030.

After offering a miserable trail of transition crumbs at a snail’s pace, Agriculture Minister Gayle Tierney had to allow guitar makers, commercial firewood operators, seed collectors and other minor forest producers access to compensation. But she didn’t mention how the government planned to address the upcoming firewood shortage.

Affected timber communities and workers crave certainty to sort out their financial commitments and give assurances to mortgagors. Simple questions like how much they will receive and when are left unanswered. Tierney added to the anger and frustration of hundreds of businesses within affected communities when all she could say in a vague statement:

Other businesses heavily dependent on the native timber industry, will also be eligible for the next round of the Timber Innovation Grants.

Many felt the transition policy was ad-hoc and based purely on ideological grounds. Andrews tried to justify that the industry needed to close because it ran out of resources. However, this was of its own making. For example, they allowed unreasonably excessive protection buffers around areas where rare or endangered species were detected and delayed the signing of the annual Allocation Order for eight months until May 2019.

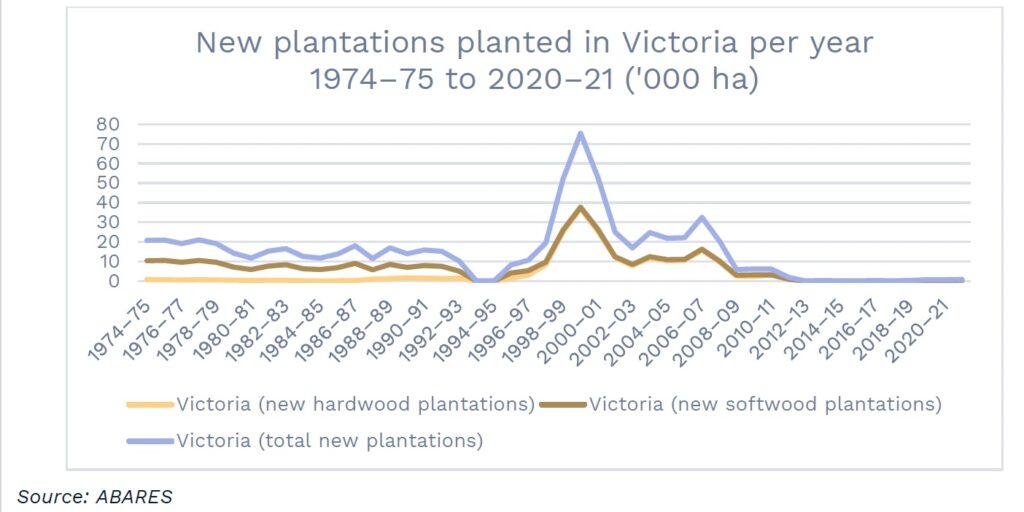

Like Western Australia, the planned replacement for the loss of high-value hardwood products in Victoria is pine plantations. The government trumpeted their plan to transition the timber industry from native forests to plantations within ten years. However, they ignore the biological fact that it takes 25-30 years for new plantations to mature and produce timber suitable for sawing. It shows the government’s plan was always a fantasy divorced from reality.

The plan also ignores the challenges associated with plantation expansion, particularly in the Gippsland region, including insufficient suitable and affordable land within an economic distance to mills. Also, poorer wood quality makes plantation-based resources unsuitable for many existing mills.

The problem is that softwood timbers don’t have the same unique qualities as hardwood and are unsuitable for many applications where those qualities are critical. Softwoods lack strength, hardness, and dimensional stability and possess more degrade qualities than native eucalypts.

Victoria will no longer be a major domestic producer of appearance-grade timber. It accounted for about 60 per cent of sawn timber output in the state and 42 per cent nationally. Nor will it be the centre of further manufacturing hardwood-sawn timber into value-added engineered wood products that generate a lot of jobs.

Australian hardwood-sawn timbers sell for 3.5 times the price of Australian softwood-sawn timber and generate much greater value-adding and job creation than softwoods. A lot of Victorian hardwood that is not appearance grade is manufactured into products where its unique beauty is on display, such as staircases and exposed Masslam laminated beams.

The government’s flawed forest policy and lack of a rigorous strategy have led to declining timber availability and sawlog output. They did not support VicForests when they allowed areas to be removed from harvesting despite existing and excessive reservations, bushfire losses and activist lawfare. VicForests’ “operable area” was reduced from 450,000 in 2014 to only 160,000 hectares in 2022.

Subsequently, native forest hardwood sawlog production declined and has not been balanced by increased plantation sawlog production. Since 2019, there has been a reduction of 50,000 hectares of plantations and a 30 per cent reduction in log supply from forests and plantations. The total log supply from native forests, hardwood, and softwood plantations has declined by three million cubic metres annually.

In February this year, over 1,000 hectares of pine plantations went up in smoke when bushfires ripped through the Mount Lonarch region, west of Ballarat. This follows the loss of 6,000 hectares during the Black Summer 2019-20 fires.

Despite Andrews announcing a review of the Forestry Plan in July 2020 to safeguard regional jobs and outline how Opal Australian Paper would transition to an entire plantation-based supply to ensure it operated until at least 2050, there has also already been a loss of about 3,300 direct jobs and 10,000 secondary dependent jobs. Add to that coupe closures and mill closures, and it is more than fair to say the plan is in tatters.

Many businesses that have worked in the timber industry for generations face bankruptcy because the government has not provided the fair compensation package they were promised.

The flow on effects

The viability of FPC in Western Australia is not rosy. With a massive revenue fall, the government has had to inject $25 million to keep it afloat. Their financial forecasts estimate a drop to $120 million in sales revenue this year, and then, like the phoenix rising from the ashes, their revenue increases. By 25 per cent in subsequent years, even though they have no idea what will constitute that revenue. Inevitably, as money dries up, staff will have to go, adding to the job losses.

In Victoria, the government quietly stripped VicForests of its business corporation status in September last year. In March this year, it announced VicForests will cease to exist on 30 June 2024.

VicForests was forced to publicly defend itself after numerous false and misleading claims were aired publicly after the closure announcement. Not once, did the Labor government step in and publicly defend its agency or hard-working employees. Not one word, effectively ignoring its existence and the existence of a formidable professional department that existed for many years before it. It is not surprising since the government overtly supported the activists in their desire to destroy the native forestry industry in the state.

Already, firewood is becoming a scarce commodity. The Western Australian Minister for Forestry reportedly panicked and ordered the production of 120,000 tonnes of firewood from high-value logs, thus preventing the manufacture of furniture and flooring products.

Demand for the world’s most environmentally responsible building material won’t stop due to the Western Australian and Victorian governments’ decisions. Demand will continue to grow, and builders and consumers will use ecologically unfriendly substitutes. Take flooring, for example. Consumers will be forced to use non-renewable or chemical-rich flooring products such as vinyl, carpet, tiles, or imported timber from poorly managed forests without hardwood timbers.

The flow-on effects of ending the harvesting of native forests are seen widely across the economy in Western Australia. One example is Australia’s only silicon manufacturer, utterly blindsided by the government’s shock announcement. Simcoa requires a source of carbon to make its product. This carbon can be derived directly from coal or by turning wood into charcoal through heating.

Simcoa used a combination of charcoal derived from local jarrah to produce its high-grade silicon, a key input for solar panels and battery technologies. Not all timbers are the same, as some absorb additional minerals from the soil, affecting the end product’s purity when converted to charcoal. They usually used about 140,000 tonnes of jarrah a year.

They imported their coal from Columbia, the only country with a high enough quality suitable for silicon manufacturers. The loss of the charcoal means they would have to increase coal imports from Columbia by an additional 25,000 tonnes.

The decision to halt native forest logging in Victoria did not include community forestry operations. These activities are operated under Forest Product Licenses, mainly in western Victoria, to harvest wind-thrown timber, thinnings, and single tree removals. These operations supplied commercial firewood, fence posts, posts and rails and logs to produce high-value products such as furniture and musical instruments. They were mainly in Wombat, Mount Cole, Pyrenees, Lederberg, Cobaw and Enfield State Forests.

However, VicForests announced they would end these activities on 5 February 2024 because of the risk and cost of litigation to taxpayers. The 200-member Wombat Forestcare community group took VicForests to court alleging breaches to survey for threatened species. Wild storms hit Wombat State Forest hard in June and October 2021, and VicForests decided to clear debris after the storms to make the forest safer. Following the decision, the group’s spokesperson, Amy Calton, said:

It was really special to know all the forests in Victoria were now safe and protected. I am exhausted and relieved, and a huge part of my heart is suddenly settled that we can say on 5 February native forest logging did end in Victoria.

The seed collection services provided by VicForests are also under threat. Seed collection contractors are part of the transition package offered by the government. The timing couldn’t be worse. For the first time in 28 years, flowering in the ash forests did not occur as predicted. Repeated fire events mean Victoria’s ash forests are on the brink of ecological collapse as they will have little capacity to regenerate naturally.

VicForests and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning undertook the largest sowing event in Victoria’s history following the 2019-20 fires. They resowed over 11,500 hectares of ash forest. However, more than 10,000 hectares could not be treated due to a lack of seed, making it difficult for those areas to recover. The other concern is that at least 143,000 hectares of regenerating fire-killed forest are highly vulnerable to another fire event before they reach seeding maturity.

The irony is that the closure of the timber industry in Western Australia and Victoria has come simultaneously with the world’s efforts to decarbonise and phase out plastics. It has led to a significant increase in demand for timber products and a substantial increase in hardwood product imports. The volume of hardwood imports into Victoria has increased by nearly 40 per cent since 2019. Sawn wood and mouldings make up most of the imports.

By volume, many of Australia’s hardwood imports are from Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia and China. Eighty-six per cent of imports come from countries with lesser environmental controls than Australia.

The Heyfield sawmill, 49 per cent owned by the Victorian government and operated by Australian Sustainable Hardwoods, began importing sawlogs from Tasmania immediately after it was announced native forest logging would cease at the end of 2023. Not only that, but they were also offering above-market prices for the logs. Local family-owned sawmills in Tasmania were caught in the crossfires as they couldn’t compete commercially.

It was particularly galling to the Victorian timber industry to learn that the Andrew’s Government would happily close its timber industry, put thousands of workers out of jobs and be a shareholder in a business aggressively buying timber in Tasmania to bring back to Victoria.

The Victorian Government was accused of political bastardry when they tried to quash all demand for quality hardwood used in buildings by “strongly recommending” to the Housing Industry Association (HIA) that builders cease using native hardwoods in flooring, staircases, beams, doors, windows, architectural features, decking and cladding.

Since they decided to close the industry, Victorian hardwoods have been preferred by builders and consumers, which has become an inconvenience to the state government as it tries to dictate to its builders and consumers what timber they should use. To cover its tracks, the government recanted on their strong recommendation and told HIA members that their industry could still access hardwood supplies from Victorian timber mills.

If the Victorian government had its way, Melbourne-based ARM Architecture would not have obtained the contract to refit the Sydney Opera House Concert Hall, winning several national Timber Design Awards. Hardwoods were used in the original walls and again for the refit.

Heyfield’s Australian Sustainable Hardwoods has supplied appearance-grade sawn timber and laminated beams for so many magnificent timber-based building projects across Australia. A recent example was Masslam laminated beams, and floor and roof systems made from certified Victorian ash in the University of Tasmania’s West Park campus in Burnie, Tasmania.

We now hear that the extreme green activists in Victoria are pressuring the Labor government to ban the import of hardwood products from other Australian states. It will only serve to increase imports from countries like the Solomon Islands, Indonesia, Borneo and Malaysia, where environmental outcomes of their timber harvesting operations are markedly more destructive than the sustainable and regulated Australian operations.

Concluding remarks

The Queensland government started the trend to stop native forest harvesting in 1999 when they announced plans to end timber production in state forests in the south-east region on 31 December 2024 after an agreement with the timber industry and environment groups. They planned to provide an alternate, plantation-based resource to the industry by upscaling the hardwood plantation program to 20,000 hectares by 2025.

However, the plantation program failed miserably. By 2019, about 15,000 were planted, but an independent review confirmed what the industry knew – most of the established plantations were performing poorly and would not deliver the intended alternate hardwood resource.

The government rushed into an untested plantation program, choosing marginal sites and struggled to match suitable species for the sites selected without any research benefits such as improved plant genetics. Consequently, pests and diseases led to inferior growth rates and the commercial failure of large areas of plantations.

While the government is still committed to phasing out native forest logging at the end of 2024 in some areas and by 31 December 2026 in the Wide Bay and South Burnett regions, it has no idea what resource will replace the native timbers.

The former New South Wales Liberal government toyed with ending native forest logging in 2022, but its coalition partner blocked those plans. The new Minns’ Labor government is committed to establishing a Greater Koala National Park covering a large selection of remaining state forests in the north-east. It is under increasing pressure to extend the reserve system and end native forest logging across the state.

Then shadow Minister for Natural Resources, Courtney Houssos told the timber industry before the election:

I note that the Victorian and Western Australian Labor Governments have announced policies to end native forest logging, and we have seen the loss of jobs and the closure of mills as a result of this announcement. This is not New South Wales Labor’s policy.

If native forest harvesting ceases in New South Wales, then the country will immediately face a shortfall in eco-friendly power poles at a time where the federal and state governments are hell bent on charging to Net Zero by electrifying everything. This requires the construction of at least 10,000 kilometres of new transmission lines. The native forestry industry is crucial for this transition.

New South Wales currently supplies 86 per cent of all timber poles in Australia. Timber is the preferred pole by electricity authorities because they last well in service, flex, do not conduct electricity, and they last at least 80 years. Converting to alternatives, such as concrete, steel or fibreglass poles, are not only more environmentally damaging, but they are a lot more expensive, which will ultimately increase electricity bills even further. Concrete poles show hairline cracks after just 50 years and have to be replaced.

The Tasmanian Liberal government remains firmly committed to its forest industry. Before the March 2024 election they made available 40,000 hectares of the Future Potential Production Forest “wood bank” to provide about 10 per cent more high-quality sawlogs, exclusive to existing Tasmanian sawmills. The Labor party pledged to support the industry using vague motherhood statements in a clear move to keep their options open. However, it is the Greens and many Independent candidates who have pledged to end the logging of native forests that focuses some attention on the result of the election.

It seems that the decisions by the Victorian and Western Australian Labor governments to end native forest logging will turn attention to the remaining states to follow suit. It will be interesting to see how long they can hold out from unrelenting activists and media pressure to cease the practice nationwide.

One thing is for certain, ceasing native forest logging will deny Australians access to high quality sustainable timber for our houses and furnishings; regional towns dependent on timber processing will be trashed; highly skilled workers will be lost; and the bush skills and equipment needed to fight emergency fires will be severely depleted.

How can Australians sit idly while they allow politicians to make opportunistic, short-term decisions to suit their own political needs and ensure our forests suffer worse environmental outcomes through management by benign neglect, and instead happily rely on imported Asian rainforest timber from poorly managed forests to continue to meet their insatiable timber demands?

What is the sense in that?

Great piece, Robert.

The WA government’s deception started with Mark McGowan signing a 20 year extension to the RFA in 2019. This gave clear commitments to maintain specific timber volumes. Alas his signature was a fraud, as are the RFAs. They were intended to provide certainty but gave none to the timber industry.

Mark McGowan made no comment about ending commercial forestry in the election campaign in March 2021. Cowardly and deceptive.

When Parkside arrive to consolidate WAs failing hardwood businesses, it was with vigour and foresight. I took Dave Kelly to the Greenbushes mill on two occasions. He waxed lyrical and made several statements of support for our sustainable industry. Without batting an eyelid black became white and it was no longer viable, trees weren’t growing and they were going to ‘save’ the forests from timber harvesting.

The current Minister, Jackie Jarvis, is equally duplicitous. She was a Commissioner for FPC for 4 1/2 years taking her sinecure and constantly supporting the industry. Once in government, her colours changed and she constantly bleats about the unsustainable native forest industry. She makes claims about the science but hasn’t conjured any to support her fiction.

The unfortunate truth is the government is presiding over the massive destruction of forests by allowing broad scale mining, expanding with the crazed rush for lithium. The entire forest between Nannup and Collie is covered with lithium leases. There is no mention of this in spinning their yarns.

Now the government is embarking on its signature forest initiative – ecological thinning. This has been said to be necessary for forest health, and NOT driven by timber production. The government is spending $150 million subsidising this program over the next three years. Again don’t believe the rhetoric.

The first areas to be ‘ecologically’ thinned are 50+ year old karri forest. Previously thinned 20 years ago these forests are hardly a priority for climate change protection. The reality is the thinning is essential for wood supply of veneer logs and nothing to do with forest health.

Lies and liars, this debacle has restored my disgust with the value set displayed by politicians.

Thanks Gavin for providing some excellent local knowledge and background that I was unaware of.

I constantly shake my head and wonder how brazenly these charlatans keep getting away with all the obfuscation and are never held accountable, except when they get voted out (or resign and run away like McGowen) which means nothing in terms of the damage they cause.

Great piece Robert.

It seems inconceivable that public policy has shifted from a sustainable “forest industry” to, as you put it, “benign neglect” leading to a far more costly “Fire industry” as a poor substitute.

Tax payers only have to compare the historic costs of management under the State Forest model to that of the National Park model.

Until Australians enjoy some visionary leadership at all levels of government, forest health will continue to decline, our forests will burn more intensely and more often placing increasing risk to rural and regional communities, insurance will keep going up, and cost of business in places like Victoria will become unaffordable driving investment away to other States – hardly a worthy contribution to the nation’s carbon aspirations.

One can only hope…

Robert,

A very thorough summary of all the true facts around this issue.

With so many voters now living in major metro areas an becoming more illiterate as to proper sustainable management of our native forests, I can’t see an end to this trend – unless strong politicians stand up to the radical activists (paid to be so through huge donations from wealthy individuals) and support the science of sustainable native forest management – as in Tasmania.

Do you send your blogs to both the radicals and native forestry supporters?

Best wishes,

Leigh

Leigh, I try and get as wide a distribution for my stories by sharing on various pages on Facebook. Australian Rural and Regional News publishes some of my stories, including this one.

There are some “radicals” seeing the stories based on some comments and feedback I get. But you can’t reason with them based on facts.

Hi Leigh.

I try and spread my blogs on many Facebook pages, admittedly mainly those supporting the forestry industry. If I tried on the activist pages, they would simply block or cancel me, so I don’t bother.

This story was also published by Australian and Region Regional Newspapers via their online page. I was told it had over 20,000 hits!

Hi Robert,

Whilst not in any way wanting to muddy the (excellently researched and presented) discussion, I do have a slight quibble with the implied notion that there are ‘good guys’ and ‘bad guys’ in Western Australian politics. No such binary exists in my mind. Some are just more brazen than others. You mention the ongoing desecration of the work done in the past by the Forests Department on the Darling Scarp caused by bauxite mining – that State Agreement hog-tying the Forests Department was gleefully put in place by David Brand’s Liberal government in 1961. The only Labor government from Brand’s time through to the coming of the alleged messiah Brian Burke in 1983 was the one-term Tonkin government of the early 70s. Similarly, the failure of the Donnybrook Sunklands large-scale pine plantings is usually put down to madcap environmentalists, although that conveniently overlooks the fact that the Forests Department issued their detailed, public, Statement of Intent in September 1975, and ‘marauder Burke’ only arrived on the scene in 1983 – so, almost eight more years elapsed under Charles Court ‘s and Ray O’Connor’s Liberal government and it still was sitting there undeveloped waiting to be shot at when Burke did surface. There is also the small matter that between the times of the Gallop/Carpenter Labor government and the still extant McGowan/Cook government there was eight years of the Barnett Liberal government.

I don’t want this to be seen as a political partisan comment (it isn’t); just a reminder that you can’t spot bastards just by the colour of their tie.

If foresters want a friend, they should buy a dog. Be wary of whoever you see going into that big building in Harvest Terrace at the western end of Perth’s St George’s Terrace for boozy, long lunches.

Thanks Max. I wasn’t deliberately trying to be partisan when having a go at the politicians. It just so happens that when I made specific references linked to government policy decisions as examples, they happened to be by a Labor government.

I didn’t mention the significant decision in the 1980s which affected forestry hugely – the amalgamation of forestry into the super department called CALM which again was under a Labor government, led by Burke.

In my other posts covering the WA scene, you will see I had a dig at Liberal governments, particularly over the bauxite mining issue.

As an aside, during our travels, I met a former Liberal minister in the Charles Court government who was set up next to us at a Carnarvon Caravan Park. He told me some very interesting stories about his time as a politician that if I shared publicly, he would obviously deny.

A very interesting character, as was his wife – Richard and Ann Shalders. So interesting I wrote a story about them as part of my “Characters you meet on the road” series on my Exploring Willow Facebook page – see

https://www.facebook.com/willow660/posts/pfbid0mHXuCmGDQE8GHPTP7zog8PRYt8GGuQd2iFfKszHeW3hhuhwU4cfPevzsKStfjeiZl

There is something very satisfying in knowing that old politicians end up living in a caravan in Carnarvon. I suppose all the good spots under Perth’s Narrows Bridge are already taken. The only thing better would be finding out they’re camping in the usually dry bed of the Gascoyne River and will get washed out to sea the next time a cyclone dumps it’s load upstream. That said, he seems like a decent bloke according to your Facebook post – I suppose we all make mistakes in life, although in a democracy you can always say it’s not my fault, the electors chose me.

The CALM reference is interesting – you do know that the last Conservator of the Forests Department (Bruce Beggs) was Brian Burke’s choice as Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet when he came to office (although to be fair, he did retire in 1985)?