Ever since humans have worn garments, they have had to wash them. Where to put the garments to dry has a fascinating history. We always think that pegs hung them. However, clothes pegs only have a relatively recent past. Before the nineteenth century, laundry was hung on bushes, limbs or lines without fasteners to hold the clothes in place.

The patent for the original clothes peg belongs to Jeremie Victor Opdebec, who designed a peg in one piece with two prongs only a tiny distance apart.

In the UK, they made pegs from willow (Salix alba) and hazel (Corylus avellana). The early peg makers in Britain were “woodland bodgers”, farmers who kept idle hands busy in winter.

In 1853, David M Smith from the USA invented a clothes peg with two prongs connected by a fulcrum, plus a spring. He is credited as the inventor of the modern articulated peg. The two prongs are pinched at the top, the prongs open, and when released, they spring closes and grips the article.

This design was improved in 1887 by Solon E. Moore with a coiled fulcrum which formed two functions – it held the wooden pieces together and acted as a spring, thus eliminating the need for a separate component.

Soon after, the United States Clothespin Company opened manufacturing pegs using this improved design. At their peak, 700 tonnes of timber each year was used to create 20,000 pegs a day. They preferred ash (Fraxinus americana) and hazel.

The peg factories

In Australia, the first peg factory opened in Yarra Glen in Victoria in 1920 by the Pioneer Woodware Company. It had the support of the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League that was looking to employ returned servicemen. A two-storey building was constructed for the factory, and it employed 15-20 people.

The pegs were made from southern sassafras (Atherosperma moschatum) sourced from the nearby rainforests. Firewood was also supplied from the mountains to run the steam engine to power the factory. First, there was a breaking down saw to cut the logs – then smaller saws to cut the timber into smaller sizes. The timber was then sent to the machines that fashioned the pegs. Finally, on the upper floor, the pegs were packaged into boxes.

A small clothes peg factory in Bunbury, Western Australia, started operations in November 1923. It was known as Baldocks Peg Factory, owned by Arthur Baldock. The factory was ravaged by fires twice in a short space of time in 1924 and 1925. The second fire destroyed the automatic shaping machine imported from Germany. The machine had a battery of knives capable of turning out shaped pegs every second. By 1930, the factory had increased production from 15,000 pegs per week to 80,000. I read the factory utilised what was generally considered a useless wood, red gum or marri (Corymbia calophylla), although it was most likely they used tuart (Eucalyptus gomphocephala). This was a common tree around Bunbury and was used to make gears for flour mills and hard waring parts for ship rigging etc. It is a light coloured wood, extremely hard to split because of its interlocked grain which would have been a valuable property when used as a peg.

In 1925, a dance hall that was converted to a 1,000-seat cinema in the village of Blackheath in the NSW Blue Mountains became a peg factory. A sawmiller logged a nearby forest to supply the timber for the pegs. The factory was still in operation in 1938 when it was reported an employee nearly had his hand severed while feeding timber through the circular saw. In 1946 the hall was known as “The Peg Factory”. Not much more is known about this factory and when it closed. I cannot find what timber was used to make the pegs, but it is believed to be sassafras, as it does occur in the Blue Mountains. The northern population of sassafras in New South Wales has narrow leaves and an entire margin, in contrast to Victorian and Tasmanian sassafras, which has coarsely toothed leaf margins.

A large factory producing bobbins, brooms, bungs and clothes pegs was operated by Aitken Woodworking Company at Montrose in Hobart. It first started in Footscray in Melbourne during World War I to make bobbins for the textile factories that couldn’t be sourced from its traditional market in England. While European beech (Fagus sylvatica) was considered the superior timber for bobbins, Australian myrtle (Nothofagus cunningahamii) from Tasmania proved to be suitable. The factory also imported sassafras from Tasmania to make its clothes pegs. The directors decided to shift the factory to Tasmania in 1924 to be closer to its raw materials. They produced about 300 pegs a minute. The knives used on the shaping machine were made from old Ford axles simply because it was considered the best steel for the purpose. The factory closed in 1929.

The Yarra Glen factory closed in 1926 and Pioneer Woodware Company also moved its operations to Tasmania, setting up in New Norfolk mainly because the Victorian sassafras stained the clothes. The Tasmanian sassafras was more plentiful and did not stain the clothing. Sassafras was sourced from the nearby Tyenna Valley forests via a specific concession. The timber procurement complimented the operations of giant Australian Newsprint Mills (ANM). ANM bypassed the understorey sassafras as it chased the big mountain ash for its pulp and paper mill.

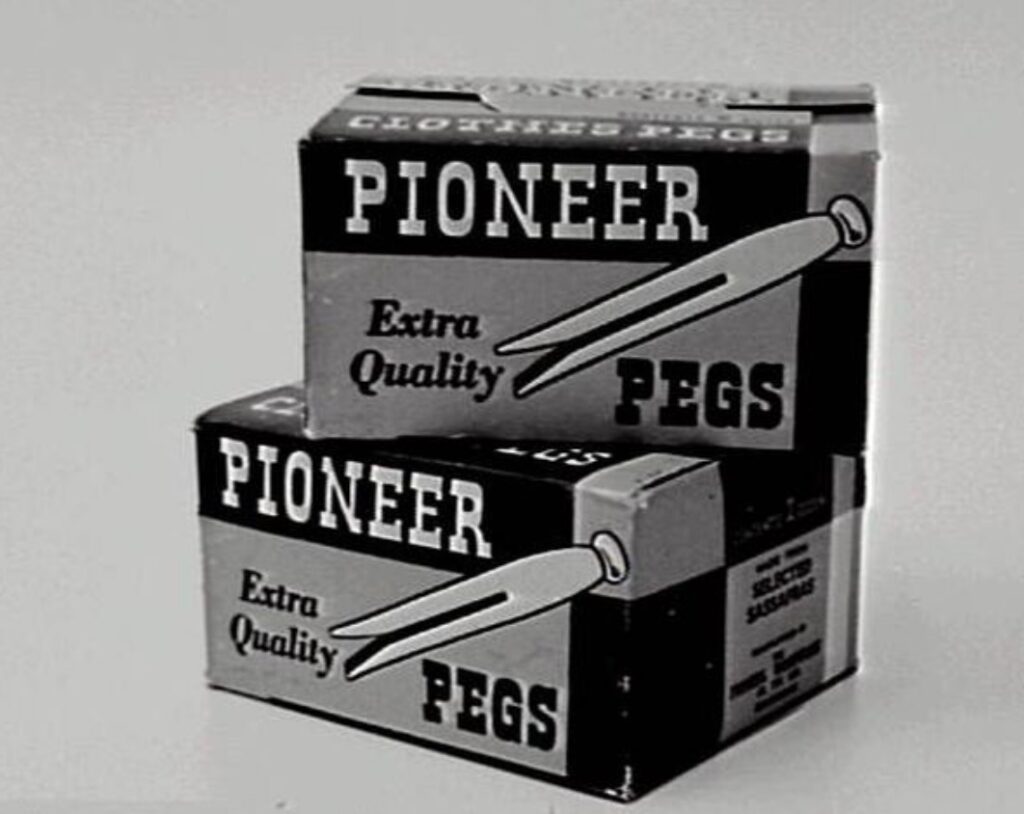

The factory employed 100 people, primarily women, producing 1.4 million of their famous dolly pegs per week. They packaged two dozen pegs in cardboard boxes. A new book provides a great history of the factory.

Using sassafras, another factory operated at Devonport by Timber Products P/L produced 6,000 pegs a month, or more than 10 million a year. It ran in the 1950s but very little is known about its history.

On Christmas Day in 1941, a fire broke out at the New Norfolk factory. Fortunately, it was spotted early and put out by the local fire brigade before significant damage.

During World War II, large quantities of clothes pegs were produced from Tasmanian sassafras – up to 60,000 cases annually. The Commonwealth government was concerned about continuing the supply of sassafras at those production levels. An experiment in using Victorian mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) for making pegs proved unsatisfactory because they were below the required standard. Pinus radiata was suitable if the pegs could be bound with wire to prevent splitting. But during the war, there was significant demand for wire for other essential purposes. The Commonwealth Controller of Timber appointed a Deputy Controller in Tasmania to increase the export of sassafras to Victoria to aid in producing clothes pegs, but nothing resulted from this proposal.

In 1948 tragedy struck the New Norfolk factory, which burnt down. At the time, it was the largest fire ever in New Norfolk. The loss was a problem as the factory was the leading supplier of pegs throughout Australia, and it made headlines around the country. To avoid a national shortage, an emergency factory had to be set up before the new one was opened the following year. It could only produce square pegs, but it filled a gap.

The company introduced springs to the dolly pegs in the late 1950s. In April 1960, the Derwent River flooded and caused damage to the factory’s machinery and ruined stock. The Federal Government removed import duties in that same year, and the peg market was flooded with cheap foreign pegs. The Pioneer Woodware Company faced a financial crisis that culminated in ANM buying the business in 1962. After some years of profitable operation under ANM, equal wages for women and increased imports from China were blamed for the final closure of the peg factory at Christmas 1975.

A local Councillor was outraged by the decision, saying, “housewives could still afford to buy Australian pegs even if the price was doubled. Most housewives spend about $1 a year on pegs … I can’t see another dollar a year making any difference”.

Making pegs

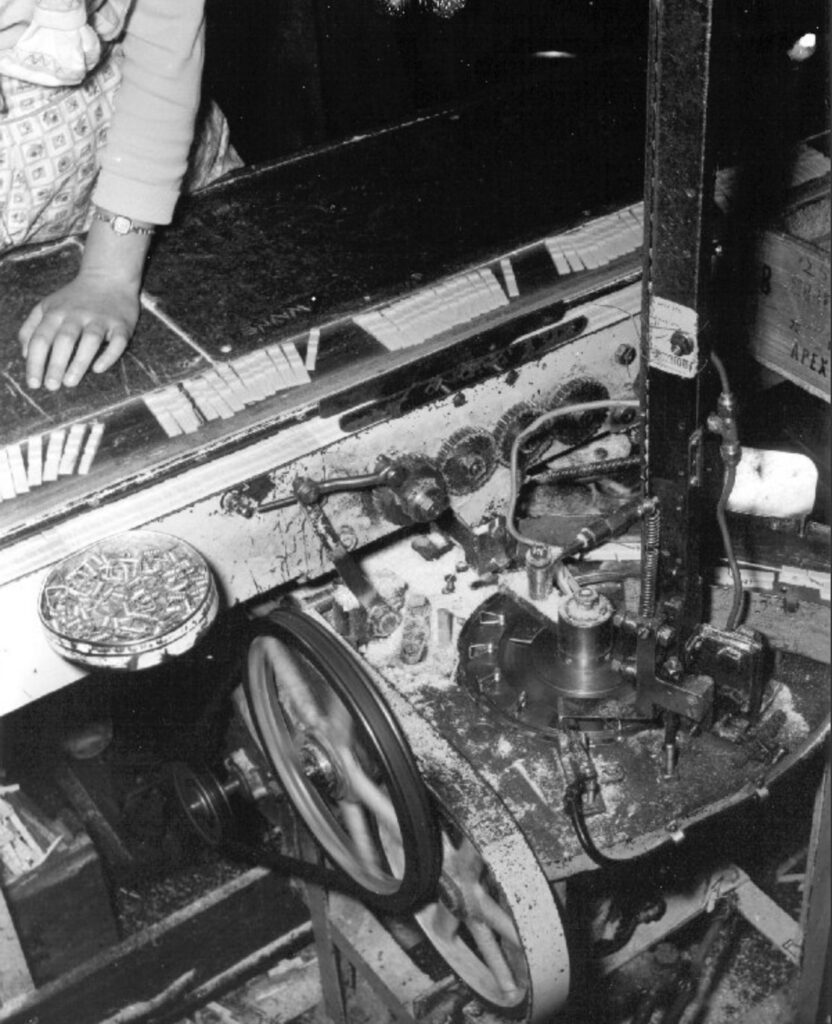

An excellent article in The Hobart Mercury describes the manufacture of wooden clothes pegs in detail. In summary, the logs that provided the timber for pegs arrived from the bush and were initially processed and broken down like a sawmill operation. Logs were placed on a circular saw bench and cut into planks. The planks were then sent to a smaller saw to cut into four-foot lengths. Another saw bench with multiple blades converted the timber into small square laths. Laths were then placed on a travelling belt to another multiple saw to be cut into the finished length of the peg.

The timber passed saws where they were cut into peg blanks, fed into a peg shaper machine, and sent through a slotter. Next, they were placed in a bath of oxalic acid for five minutes, which bleached them white.

The pegs were then placed in a rumbler heated to 180 degrees, a hexagonal-sided barrel, and rotated by electric motors slowly for several hours until dried. It sped up the drying process, typically taking about six months. Next, a preparation wax was applied to give them a polish. The pegs were then checked for faults and the good ones packed by hand either in cartons or in bags.

Those in the bags were loose in 60 dozen lots, but those in the cartons were packed in cellophane wrappers, each containing two dozen.

Tasmanian sassafras

I remember many journeys walking through the myrtle and sassafras rainforest in Tasmania, especially after rain (a common occurrence in the north-west of the state where I worked in areas that received over two metres a year), where I would enjoy the sarsaparilla scent of the sassafras leaves. Its bark had a more cinnamon odour.

Southern or Tasmanian sassafras is frequently utilised for its timber, which is solid yet light and does not tend to split. While it has poor in-ground and external durability, it is great for internal applications. Due to its even grain, it is quite soft and easily worked both by hand and with tools, lending itself to use in furniture, panelling, joinery, veneers and woodturning. Sassafras is a fragrant timber and has traditionally been used in clothes pegs due to its low tannin content and the fact it did not stain clothes.

If the timber is infected with a staining fungus, it produces streaks with a rich brown colour called blackheart sassafras, a much-favoured decorative feature for woodturning purposes.

Until the Pioneer Woodware Company peg factory opened in 1926, sassafras had little commercial value in Tasmania. They bought out the sawmill operation and tramlines built by J. M. Mayne at Kallista to reliably source the timber. The tramline brought the sassafras from the upper reaches of the Tyenna Valley to the railhead at Fitzgerald, where the logs were broken down at a nearby sawmill. From 1927, the logs were sent to a sawmill at the New Norfolk factory. A subsidiary company called Kallista Timber Development Company supplied the sassafras in the 1930s.

Many small sawmills in the state’s north-west were principally set up to cut sassafras for the burgeoning wooden peg market from the late 1920s to the 1950s. They mainly were located at Parrawe, Nietta, Preolenna and West Takone near sources of cool temperate rainforests.

I actually worked at the peg factory on the spring machine. It was my first job after leaving school.

I assume Judith you mean the New Norfolk factory?

Dear Robert,

When you get time to have a look, you will find it interesting to find out about the Wynyard Sawmilling Co, which had a massive output of handles for Titan and other Australian makers of garden equipment handles plus carpentry, and also a huge trade in bobbin cores for the textile industry in the UK.

I know some of it, but not all of it, being a bit too young and on the wrong side of the Blackwell family, who owned WSC.

Cheers Rex

Thanks Rex. I will see what information I can find, and whether it will be enough to write a story.