Every Fraser Island visitor has seen or knows about the Maheno wreck on the eastern shore about five kilometres north of Happy Valley. These days it is a tourist attraction and photographic stop. It must be the most photographed piece of rust in the world. The rusted remains, however, bear no resemblance to the luxury liner that plied its trade between Australia and New Zealand and the war-time hospital shipping the Mediterranean. Neither does it bear any resemblance to the wreck the locals used before it deteriorated under the onslaught of the sea and winds.

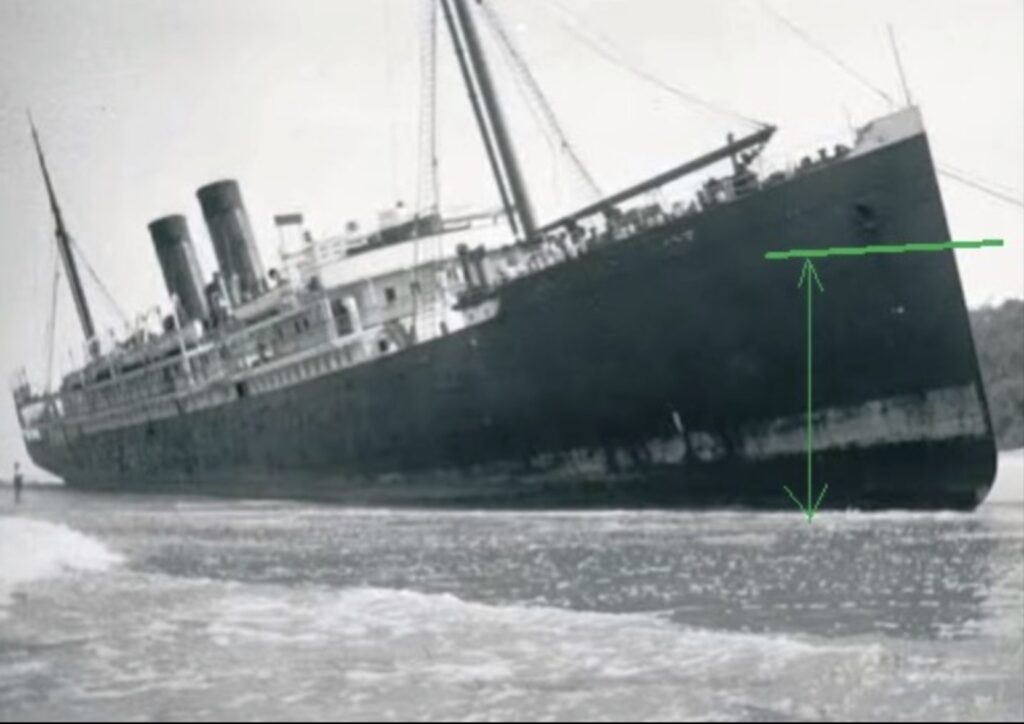

Last week 88 years ago, Fraser Island’s famous wreck washed ashore and became one of many of the island’s tourism icons. Initially a major curiosity – a wedding venue, a source of building materials, a derelict fishing platform and a sheltered campsite on the beach – it now sits forlornly, throwing its last shadows before it disappears. To help visitors understand the size of the liner, about 60 per cent of the Maheno is buried and intact, 30 per cent has rusted away, and only 10 per cent is visible.

The Maheno has a colourful history which not only makes a great story, but has captured the imagination of visitors to Fraser Island.

The Union Steamship Company of New Zealand was once the biggest shipping company in the Southern Hemisphere and New Zealand’s biggest private employer. The company was established in 1875 at Dunedin, before the days of accurate charts, proper lighthouses and safe harbours. Three of the first five ships built by the company sank within a short time of launching. The wrecks of ships built by the company are scattered around New Zealand, Australia and the South Pacific, but nowhere more thickly than in Tasmania and the dangerous bar harbours of Greymouth and Westport.

Despite the wrecks, the company made money by offering safe, high-quality service to its customers. Owner James Mills knew the railways would kill the short-distance work of his company, and thus he shifted his focus on securing trade on long-distance routes and built big ships for that purpose. Their main trade routes were the New Zealand coastal, the trans-Tasman, and the Bass Strait routes. They also operated many Pacific Island services and, from 1890, began building new ships, especially for these routes. The company also ran across the Pacific.

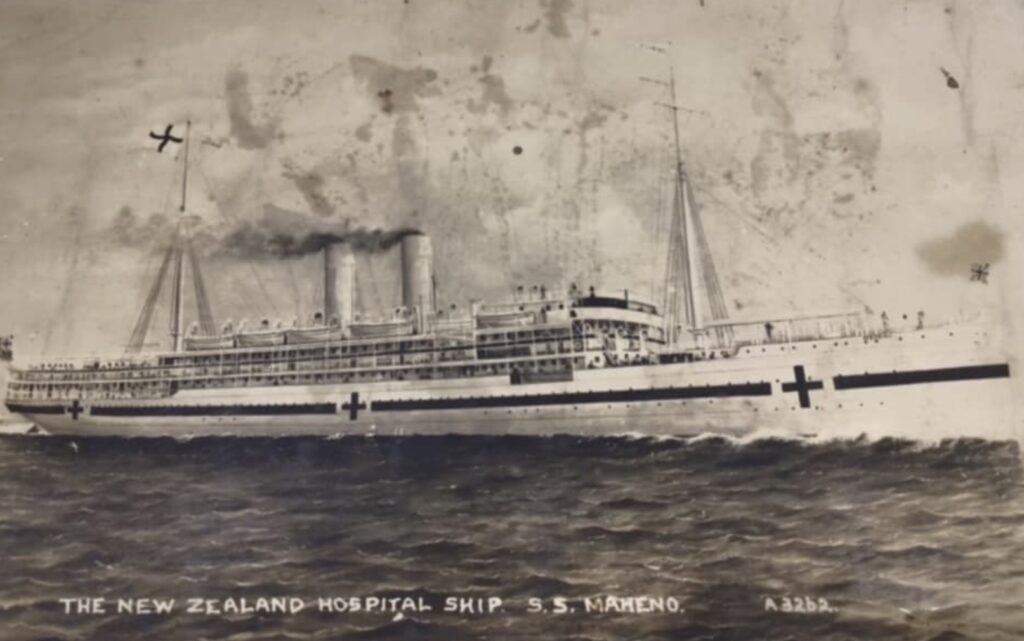

TSS Maheno was built in Scotland in 1905 for the Union Steamship Company as a luxury passenger ship on the lucrative trans-Tasman crossing. She was designed for the horseshoe service between Australia and New Zealand and boasted beautiful accommodations for 234 first class, 116 second class and 60 third class passengers. As soon as she entered service, she broke records for the fastest passage.

The Maheno was the world’s first triple-screw steamer powered by coal. However, she was very expensive to operate, requiring large quantities of coal. So, in 1914, the company replaced the direct drive steam turbines with geared steam turbines that ran on oil and the middle propeller was removed, which made her more economical to run.

However, at the outbreak of World War I, the New Zealand Government requisitioned the Maheno for war service.

She was converted to a hospital ship by its owners. During the war, she made nine return trips between Britain and Egypt and, for three months in late 1916, was in the English Channel, taking 16,000 wounded soldiers from France to England after the Battle of the Somme.

(Left) The Maheno as a hospital ship during WWI.

After the war, the Maheno returned to her owners, who restored the ship to its original condition, and she resumed her work on the trans-Tasman service.

After 30 years of service, her time was up as the newer and larger passenger liners outclassed the ageing liner. The reduction in passenger numbers during the Great Depression was also a factor in her retirement. In 1935, the ship was withdrawn from service and put up for sale in Sydney. The only interest was from Japanese shipbreakers. For the princely sum of £11,750, she was sold with all her furniture and fittings. Another Union Steamship Company ship, the Oonah, was sold simultaneously to the Japanese firm.

To save money on a tug towing the two ships in tandem, the Oonah was to tow the Maheno to Japan via a 270-metre 6.75-inch wire rope. They removed the propellers from the Maheno, and she carried a light ballast and 300 tons of coal to provide auxiliary steam for the winches to handle the heavy tow ropes and to operate the dynamos for lighting.

On 3 July 1935, the two ships left Sydney Harbour and turned north. Good weather prevailed until 8 July, when the ships encountered an unseasonal winter tropical low north of Moreton Bay (it has been incorrectly called a cyclone). They struck the full force of the low when they approached Sandy Cape at the northern end of Fraser Island.

The tow rope between the vessels parted, and the Maheno, with a skeleton crew of eight men under the command of Captain Tanaka, began drifting south-east of the Cape. They hastily made two sea anchors from canvas hatch covers and lathes to try and turn the ship’s head into the gale. However, the Maheno was at the mercy of the seas with the strong easterly gale without the propellers and only a light ballast. The crew aboard the Oonah tried to re-establish a tow connection, but under the rough seas, they had no hope of getting close enough to the other ship.

During that night, the Maheno was smashed by the mountainous seas and headed towards the sandy shores of Fraser Island. By 8:00 pm, the low was centred in Hervey Bay, and wind speeds reached 82 kilometres an hour. The Oonah sent a radio message stating the tow line had broken, and the Maheno was drifting helplessly towards the shore. They managed to get in touch with their brokers, who arranged a salvage tug, The Carlock, to leave Brisbane on Tuesday morning, 9 July, to search for the Maheno. During the night, as it headed north along the coast of Fraser Island, it unknowingly passed the stricken Maheno.

The light keepers at Inskip Point, Sandy Cape and Double Island Point were alerted and kept a watch throughout that Tuesday for any signs of the ships. Visibility was bad throughout the day and it was impossible to see more than a couple of miles out to sea. The Inskip light keeper, Oscar Walding, was quoted as saying, “it will be a miracle if a ship without engines can live in a sea like this. There is a tremendous swell, and the wind is driving the sea up in a frightful way”.

The Courier Mail newspaper hired a Fokker aircraft with a staff photographer to search for the missing ship. At 10:30 am on Wednesday, they located the Maheno after she went aground on the ocean beach of Fraser Island the previous afternoon.

The crew managed to get ashore on a lifeboat with the assistance of tourists who had walked up from Happy Valley. They pitched a camp under tarpaulins above the beach. The Oonah came within half a mile of the stranded Maheno, exchanged signals with the captain and continued southward to shelter in Sandy Strait. The harbour master and a policeman from Pialba inspected the wreck reporting that the Maheno had a hole in her starboard with flooding in the engine room.

The next visitor was an expert in marine insurance and salvage who flew to the island. While he said the ship showed no sign of a broken back, he did think it would inevitably happen. He also believed no tug could move her off the beach. The tides and wind created a sand bar on the port or shoreside of the ship, and a deep gutter had formed on the seaward side. Because the vessel developed a list of about 12 degrees seaward and there were fears the Maheno would tip over, the crew salvaged their stores and belongings.

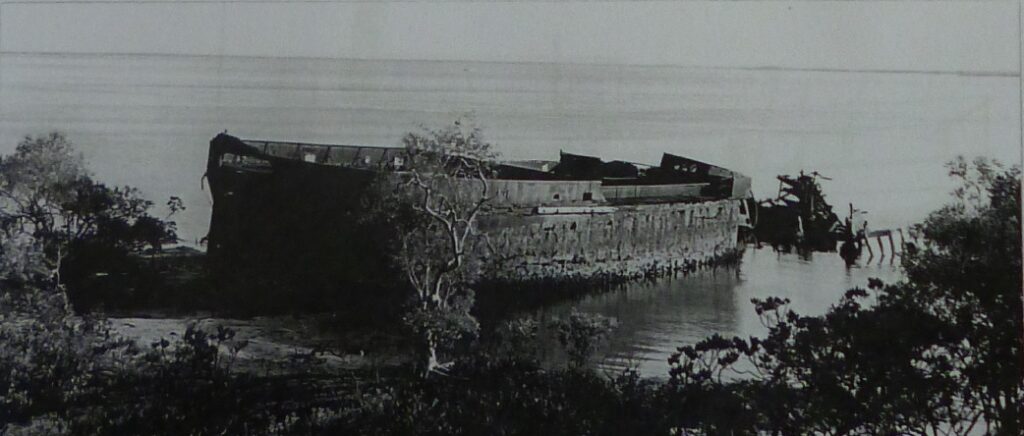

The Maheno not long after beaching. Thanks to Nathan Smith, the green line in the photo shows how much of the stricken ship lies above the sand and how much is buried below.

Customs officers arrived from Brisbane on 13 July. Because the ship was not Australian owned, customs duty was payable for any items brought ashore. The two captains inspected the ship together and decided they couldn’t salvage it. Hans Bellert, a dugong fisherman who maintained the telegraph line from Bogimbah to Sandy Cape and Charlie Mathison, a gravel barge operator, were engaged to deliver one-ton wire ropes and canvas bags to the Maheno via a whaleboat and overland via a truck. The crew tied the ropes to the Maheno to try and hold her upright. The canvas bags were filled with sand and buried to act as anchors for the rope.

The seas continued scouring sand around the bow and stern of the ship, creating a tremendous strain on the middle of the hull. The sand was washed inside her hull, burying much of the furniture and fittings. The crew unsuccessfully attempted to pump the sand out.

At the end of July, the Oonah left to continue its trip to Japan. Captain Tanaka and two crew remained to watch over the Maheno. It was important for the new owners not to have abandoned the ship. Otherwise, it would have become the responsibility of the Customs Department to dispose of it.

In October, a salvage engineer from Japan arrived to inspect the Maheno. He believed the ship was not severely damaged, and most waters came in through broken port holes, not the hull. Soundings were conducted to see if they could dredge a channel to get the ship into deeper water.

Meanwhile, one of the customs officers, Dudley Weatherley, was engaged to be married and had to delay his wedding three times due to several factors before he was transferred to Fraser Island. To overcome further delays, he requested to have his wedding on board the Maheno, which Captain Tanaka approved. The wedding was held on 14 January in the music room at 3:30 pm to coincide with enough time after the high tide to allow guests to walk to the ship [footage of the wedding in the video link above starts at 2:21]. Everyone had to climb a nine-metre vertical rope ladder up the ship’s side to board the vessel. The bride and groom spent their honeymoon on the island near the well-appointed camp for the customs officers.

The next day, water was pumped from the ship’s hull to see if she was severely damaged and could be made watertight. They found out that the constant battering of the sea opened the plates of the hull, allowing the water to enter. On 20 January, a decision was made to abandon the pumping operations, and the Maheno was left to lie where she was.

(Left) Mr and Mrs Weatherley at their wedding reception on board the Maheno.

Meanwhile, the Japanese auctioned the interior fittings, furnishings, piano organs, lifeboats, scrap metal and brass, with the customs officers at close hand to collect the customs duty. One of the first items sold was the first-class dining saloon chairs. Local Stan Warry bought 92 chairs, 21 folding cabin washstands, steel bunks, plus various marine stores for his new resort at Happy Valley.

There were rumours many goods were removed illegally at night after the culprits gave customs officers bottles of rum. After the formal process of selling valuable items, locals scavenged timber panelling and teak decking to floor and line their rough breach shacks on the island.

A cyclone on 28 March 1936 caused the stern of the Maheno to sink so low that it was underwater at high tide. As a result, the ship repositioned from a 16-degree list seaward to 2 degrees landward, putting it on an even keel.

The Japanese owners finally decided to abandon the wreck without any salvage attempts. They left the once proud ocean liner to the mercy of the wind and the sea. However, enterprising locals such as Bellert and Mathison salvaged valuable timber, crockery, large glass jars and water tanks for their Bogimbah and Urangan houses.

With the Maheno deteriorating rapidly, she still provided great shelter and fishing for groups of campers who spent weeks at the site. Fishing was good when casting from the deck into the nearby deep gutters. The Bellerts used to climb down ladders into the cargo holds and catch crayfish by hand. Despite the sloping floor, locals held dances and social events on the ship.

During World War II, the Maheno and a radius of two hundred metres around her were gazetted as a live bombing range. It remained so until 1950, when the Forestry Department complained incendiary ordnance posed a fire risk. The Royal Australian Air Force used the ship to practice masthead bombing where Bristol Beaufort light bombers would swoop low along the ship’s centre line, drop their 250 and 500-pound Standard Armour Piercing bombs and pull up steeply to leave the rear gunner to straife the decks.

There were also commandos from Z Special Unit stationed at McKenzie’s on the western side of the island as part of Special Operations Australia, an autonomous unit reporting directly to General Blamey. The Unit provided the commandos with boat training, jungle craft and sabotage skills and included a highly specialised intelligence school. As part of their training, great holes were blown in the side of the Maheno using plastic explosives.

In the late 1950s, the ship split in half, causing the bow to drop, and it was no longer waterproof and hence no longer a sheltered spot to camp. When once it sat three storeys high and could be seen from Eli Creek, today, there is not much left.

(Right) Loading logging punt at McKenzie’s moored by anchors from the Maheno. Photo courtesy David Postan.

I recall doing a mercy dash to the bar at Happy Valley to replenish supplies on a camping trip in the mid-1980s. On my return on a foggy night, I actually drove past the Maheno and our campsite. She was no longer a beacon, just a wreck silently devoured by the corroding salt and sea spray.

The anchors from the Maheno were removed in the 1960s to moor the logging punts at McKenzie’s while loading logs from the beach between the jetty and current Kingfisher Resort location.

The Maheno has sat silently on the beach for nearly 90 years. Its fall from grace as a luxury liner and pride of the Pacific was sealed before it reached Fraser Island. It has been an ignominious decline for a ship that provided so much pleasure to passengers and saviour to injured soldiers.

(Left) Tourists at the Maheno, Easter 1982. Photo John Sinclair.

Fittingly, however, Fraser Island locals gathered in July 1985 to celebrate 50 years of the Maheno being part of the island’s history in possibly its last decent memorial.

The Maheno in 2020.

The Maheno isn’t the only seafaring vessel to wreck on or near Fraser Island. An extension of the northern tip of the island lies a dangerous and notorious trap for shipping, called Breaksea Spit. The spit is a semi-submerged, embryonic sand mass that extends about 40 kilometres north of the island’s northern tip in a rough north-easterly direction.

There is also the Sandy Cape Shoal of coral, about 7 nautical miles north-east from the Cape and is only covered by less than three metres of water at low tide. That meant there was only a safe passage about two miles wide. To warn ships of the danger, unmanned lightships and temporary bouys have been placed at the end of the spit from 1918-1999. The Sandy Cape Lighthouse was built in 1870, and a light was installed on Woody Island, but they have done little to avoid any wrecks.

Aborigines reported a wreck on the northern end of Fraser Island in April 1856, but there are no recorded details. The first known wreck was the brig Sea Belle in April 1857 after leaving Gladstone. She floundered on Breaksea Spit and was never seen again. There were rumours that a woman and two girls lived with Aborigines on the island and they were survivors of the Sea Belle, but they were never substantiated.

In March 1864, an American sailing ship, the bargue Panama, was driven ashore near Rooney Point, about 20 kilometres south of Breaksea Spit, during a cyclone. Two crew members swam ashore, but one drowned. At low tide, lines were cast ashore, and the rest of the crew and passengers landed safely. The owners sold the wreck for salvage. However, William Pettigrew, the sawmiller who obtained logs from Fraser Island, wrote in his diary four months later describing that a lot of the timber was burnt. He salvaged firewood from the upper poop deck. Forester Jules Tardent wrote in the 1950s that on a clear calm day the wreck could be seen near the “blue water line” about 50 metres from the shore at Rooney’s Point.

In the same month, The Fayaway left Maryborough for Sydney with a cargo of timber. It struck Breaksea Spit and was abandoned by the crew. The captain and three crew were in a jolly boat which was swamped by the breakers and capsized. Only one crew survived plus the rest of the crew in a long boat. In late February, the captain’s cabin and a portion of the deck floated into Keppel Bay, near Emu Park.

The Lombard left Gladstone in 7 April 1867 with a cargo of livestock. Wreckage from the vessel came ashore at Port Macquarie in early May, including timbers bearing the name of the ship, confirming it had been lost. It was been concluded that the vessel was most likely wrecked near Breaksea Spit or the northern part of Fraser Island because drowned livestock were observed near Indian Head on 25 April.

The Juliet left Sydney in 1871 and struck Breaksea Spit and leaked badly after the stern of the ship was damaged. The captain planned to beach the damaged ship in Hervey Bay but were forced to abandon the vessel soon after about 25 to 30 miles south-west of the Sandy Cape lighthouse. The crew reached shore in Platypus Bay and were picked up by the steamer Hercules. The Marine Board found the captain, John George Ludwig, allowed the ship, in a flood tide, so close to Sandy Cape and gross incompetence in steering a north-north-west course.

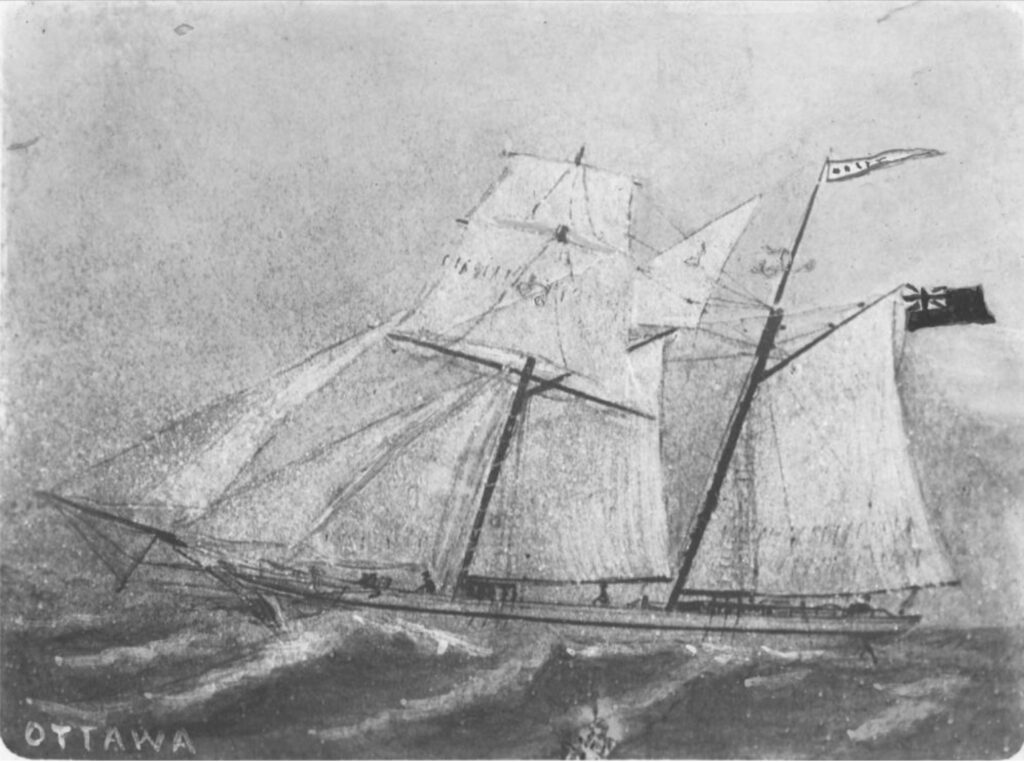

The Ottawa was bound for Mackay from Sydney and grounded just south of Indian Head in March 1878. The vessel soon broke up and was later sold at auction. The captain, Edward Witherington, and mate Thomas Mourne, were later charged to six month’s imprisonment with hard labour because “by reason of drunkenness, they omitted to steer the ship right and proper to preserve her from destruction”.

The Chinese steamer Chang Chow struck Sandy Cape shoal twice after navigating too close to land in October 1884. The ship was carrying Chinese from the goldfields to Hong Kong. It was re-floated at high tide, but there was severe damage on the bottom of the hull, causing the forward holds to fill much faster than the pumps could remove the water.

(Right) Illustration of the Ottawa used as a postcard.

The only option for the captain was to beach her and save the crew. She ended up six miles south of Sandy Cape and is now a known dive site. Divers have blasted the wreck and it now resembles an underwater scrap heap. Artefacts recovered by divers are at Maryborough’s Bond Store Museum.

The Heka left Brisbane in September 1886 in tow of the steamer Hero bound for the Cambridge Gulf in the Kimberley via Townsville. Two days later it encountered heavy sea off Breaksea Spit and foundered in deep water.

The ketch Evelyn was heading to Maryborough when it was dismasted in a gale off Fraser Island early in February 1890. The crew abandoned her and were picked up by S.S Quetta which tried to tow the vessel but the hawser parted losing the ship. The steamer Otter was sent to search for the wreck which was found ashore on Fraser Island, where it was blown up by explosives.

Wreckage from the schooner Confidence was found on Fraser Island on 25 June 1900 and the wooden schooner Waiwera struck Breaksea Spit in rough weather about two kilometres south of Sandy Cape in January 1905. The crew managed to row a lifeboat 28 miles for 40 hours against a south-east gale and went ashore at Waddy Point. Within a couple of days the ship broke up and was lost. The crew walked around to Rooney’s Point and were rescued and taken to Maryborough.

The graceful luxury ex-Italian steamer S.S. Marloo was damaged in September 1914 on its way to Brisbane from Mackay. It encountered treacherous currents and hit the Sandy Shoal hard and then beached two hours later about 3 miles north of Waddy Point at Orchid Beach.

The calm weather allowed rescuers to help transfer all passengers and luggage to shore via the ship’s boats. Once the weather turned, the ship was battered, and her back broke. Most deck fittings washed away. The hull disappeared into the sandy bottom in nine metres of water, and soon nothing was visible above the surface. She now lies 300 metres offshore.

(Left) Wreck of the Marlo off Orchid Beach.

An attempt to salvage the copper pyrite led to a large section of the deck being dragged ashore. The wreck is now part of a dive site not far from Chang Chow, but over the years was lost. In 2002 the wreckage was located again adjacent to the beach and confirmed from the air in 2021.

In May 1919, the small schooner Wave ran aground off South White Cliffs in the Sandy Strait. It was carrying rum, beer and other beverages and, for weeks afterwards, attracted the locals’ attention. The wreck was sold at public auction and successfully re-floated, arriving at Maryborough in August 1919. It received the necessary repairs and was renamed Wetona and re-registered. In 1935, it was deregistered with a note “destroyed by fire”.

The Diadem left Brisbane in late August 1935 bound for Mackay. On 1 September the boat started to leak. They tried to enter Mary River but heavy seas prevented them crossing the bar. Running out of fuel, they decided to beach the launch but in doing so, turned side on and heeled over at a sharp angle about 100 years from shore. After righting, she beached about five miles north of Hook Point.

The Canonbar ran aground in Sandy Strait, near Stewart Island, in May 1938. She was moved a short distance in an attempt to free her, but needed more assistance. The tug Oarlock was diverted to the Sandy Strait on the way from Hervey Bay to Brisbane, to assist in refloating the Canonbar, but it was considered unsafe owing to the Oarlock’s draught. The Canonbar was eventually refloated.

I also read a report that in the 1950s, what looked like “a 50-foot coal barge” lay ruined and almost buried in the sand at the water’s edge about three miles south of Indian Head. However, information about this wreck is very scant, except it may have beached in 1945.

While there have been several shipwrecks, yachts have also seen their demise around the island. One ran aground at Waddy Point, and another struck a humpback whale and sank in Platypus Bay.

Timber punts carried the hardwood timbers from the island to the sawmills on the Mary River at Maryborough. At the end of their life they were basically dumped and abandoned, some at Fraser Island. The remains of Captain Armitage’s the Geraldine are beneath the Poyungan log dump. The Dagmar was stranded in Woongoolba Creek. The Pioneer, which was wrecked in a storm, lies on the beach at Fig Tree.

The Essex was left abandoned beside the southern log dump in Urang Creek. Today, mangroves grow in her hull but the outline of the top edge of her hull is visible. The remains of the schooner Swordfish are located just south of Waterspout Creek, a permanent source of excellent drinking water for passing boats. It was a boat used by Rooney to transport sections of the Sandy Cape lighthouse.

Two old gravel barges are lying in the Ungowa area. Originally a steel twin-screw steamer, the Palmer was hulked and converted into a lighter in 1927. It was abandoned in Deep Creek in 1942 past the log dump on the southern side.

(Right) The Palmer today at Deep Creek. Photo courtesy Fishing Boating Exploring.

Built in 1844 in Paisley, Scotland by J. Fullerton and Company for the Australasian Navigation Company, the Palmer was originally a twin screw steamer with 267 gross tonnage. She was 43 metres long with an 8 metre beam and a draught of 2.5 metres. The Palmer was later bought by Charlie Mathison and used as a dumb barge, or a ship without power. She was used to carry gravel from Woody Island to Urangan from 1935 to 1937, logs from Fraser Island to the mainland, and a number of vehicles and horses from the mainland to Fraser Island. Mathison wasn’t happy that the government wanted to seize the vessel for war purposes and stop his business, so he took her deep up the mangrove-lined creek, put a hole in her and sunk her so no-one could use her.

The Ceratodus at Fern Creek.

The Ceratodus spent 23 years dredging in the Burnett River until 1921. It was brought to Maryborough, dismantled and parts were sold. The remaining hull was used as a sand barge carrying fine white sand from Bun Bun and Deep Creeks to Walkers Limited and other foundries in Maryborough for use as an excellent moulding sand in iron casting. It lies just to the south of the old Ungowa jetty near the mouth of Fern Creek after its owner used a plug of gelignite to sink and abandon her.

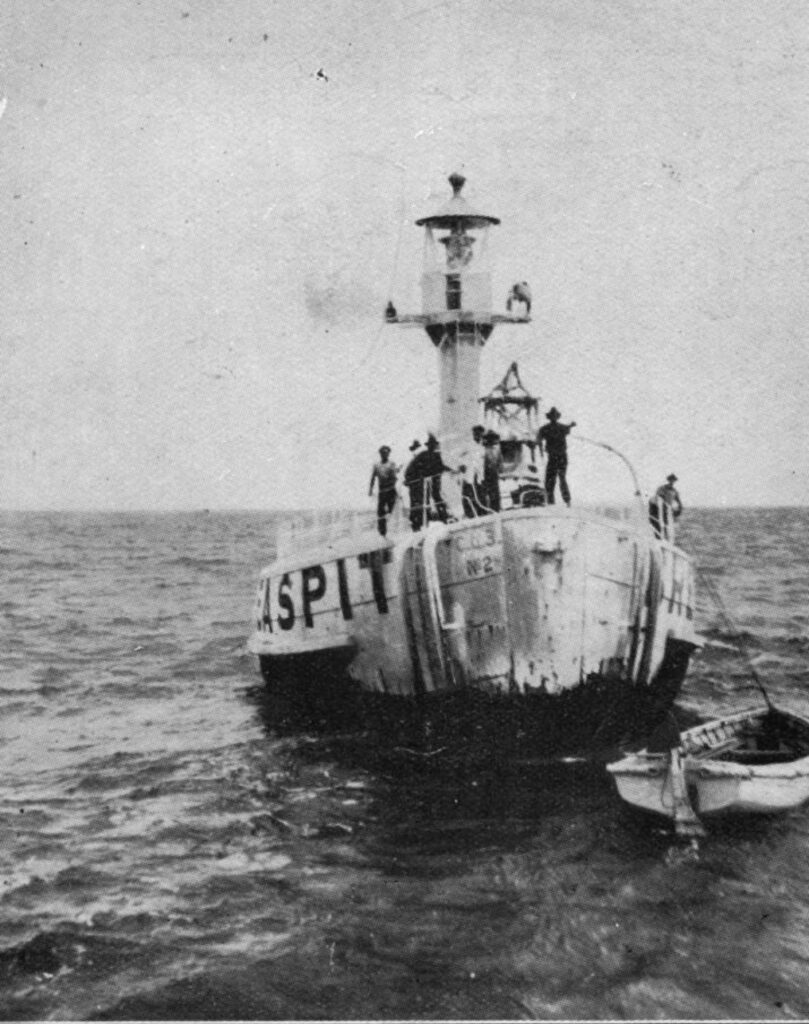

Between 1921 and 1935, the Breaksea Spit lightship broke adrift five times. During a cyclone in February 1936, the lightship was torn away from its mooring, and wasn’t found in the area, despite an extensive search. It was later retrieved from a reef about 400 kilometres east of Townsville. The lightship was rammed by the motorboat MV Gladstone Star in June 1962 and it sank. A reserve lightship was put in place along with a temporary body.

(Left) Breaksea Spit light ship 1931

But it is the Maheno which occupies the mantle as the wreck of Fraser Island. Next time you stop at the wreck to take photographs, ponder and marvel at her former prowess in her heyday – the joy she brought to so many passengers and the relief she provided to troops during wartime as she plied the waters for over 30 years.

A recent aerial view of the Maheno. Photo Indefinite Leave.

Go silently in the night, TSS Maheno.

I highly recommend reading Nathan Smith’s excellent book The Long Life and Slow Death of the T.s.s. Maheno to get more detailed information about the Maheno. While it is sold out, you can view the book through the local libraries. Nathan’s paintings of the Maheno can be viewed on the ship’s Facebook page – T.S.S. Maheno Collection.

A very interesting account of the history of a liner and its demise. Fraser Island certainly can tell a few tales and I look forward to reading your forthcoming book of this wonderful island.

Chang Chow is in 9m of water off Browns Rocks. A top dive site for fish life and being more exposed to big seas than the Marloo.

First dived Chang Chow in the 80s with URGQ and Frank Curtin. Ben Cropp dived her in the 70s.

The dumb barge south of Indian was visible from shore in the 70s and good for a snorkel dive.

The Marloo, off Orchid Beach, sits in 5m with hull intact but scours out to 11m when can see prop shaft and the oyster line along the side of the hull

Thanks Ken.

Would you be interested in contributing a blog about diving the wrecks at Fraser for a future blog, in association with the publication of my book on the forestry history of the island?

I remember catching a very large oyster fish off the Maheno when I was forester on Fraser Island in the 60’s. I think they are called by another name these days.

I am very happy that you have called the island Fraser Island and not K’Gari.

We call them oystercrackers but some call them snubnosed darts.

My father, Andy Anderson, was a Forester on Fraser Island when the Maheno washed ashore . He was one of the first people to talk to the Japanese skeleton crew. He told me that some of the furniture and fittings were stolen from the wreck. At aucton, he bought one of the saloon chairs and gave it to his father. It then passed on to him and my mother passed it on to me after Dad died. I still have the saloon chair in my bedroom.