“When a clown moves into a palace, he doesn’t become a king. The place becomes a circus.”

Old Turkish Proverb

Settlement, snow leases and the rise of the grazing scapegoat

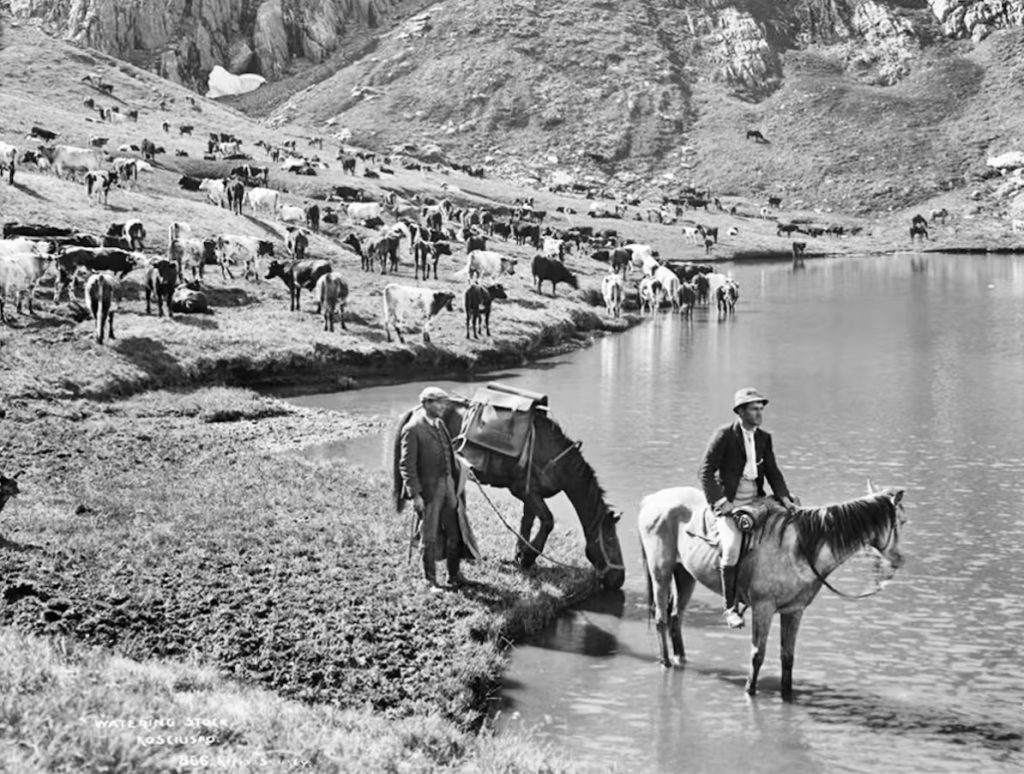

By the 1830s, white settlers from the Monaro, Canberra, and Goulburn districts were driving cattle into the Snowy Mountains each summer. The so-called “snow belt” was rarely covered in snow year-round, but after spring melt, its high plains and frost hollows provided lush pasture of tussock grass, broadleaf herbage and swamps, making them ideal for summer grazing. Below the treeline, even timbered slopes supported stock sufficiently to make the trip worthwhile. Carrying capacity was measured in hectares per sheep, not the other way around, and the grazing season ran from October to early May.

By the 1840s, the seasonal movement of cattle and sheep into the mountains was well established. The alpine pastures became a vital buffer during drought years, although some owners pushed their home paddocks harder, relying on the high country to fill the gap. Railways improved access. Gundagai’s 1880s connection from the Riverina opened the western gateway, while Cooma’s 1889 railhead provided similar access from the east.

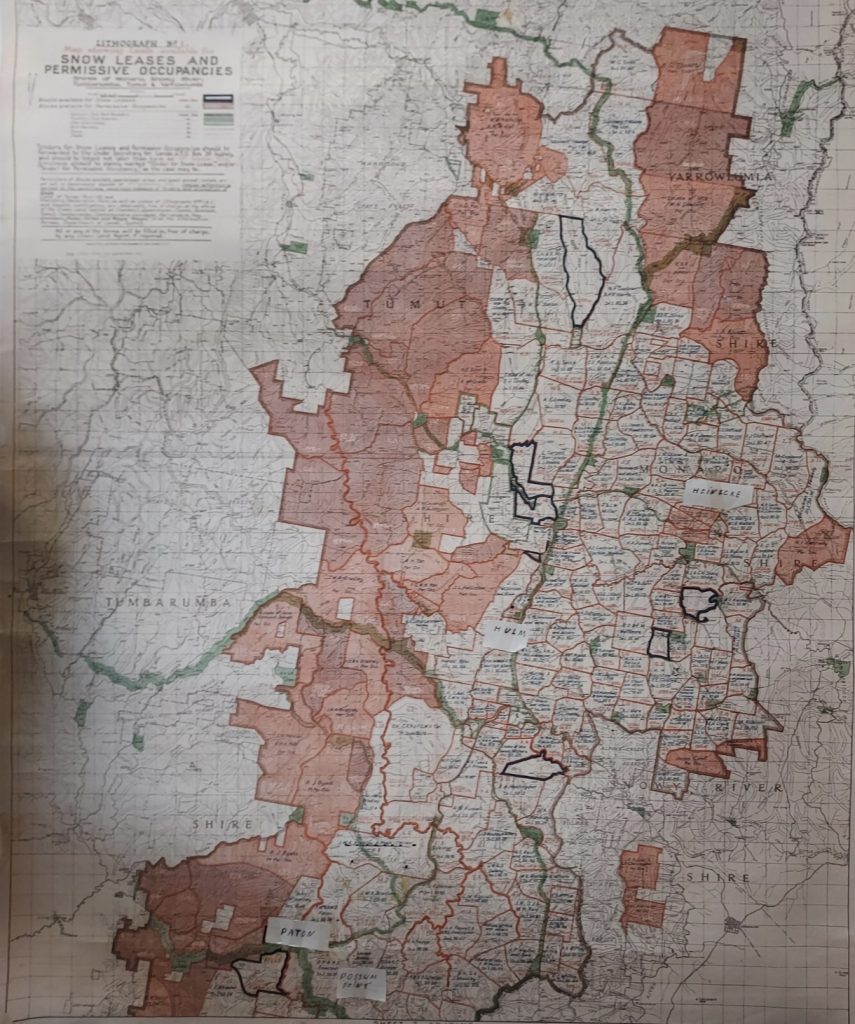

By the 1850s, pastoral leases had become common in the snow belt, formalising the practice. By the 1880s, wealthy runholders owned the best high-country plains outright. The 1884 Land Act split large leases into smaller ones, creating more titles to tender. In the snow belt, the Crown introduced “snow leases,” which granted seven-year grazing rights for up to 10,000 acres, sold by tender to boost Treasury funds before any income tax was introduced. It was good revenue from land that was only needed for part-time use.

The government aimed to profit from these leases, but by the end of 1891, only 19 of the 42 offered had been sold. Rising rents, the requirement to build fences, survey costs, and the depression of the 1890s dampened enthusiasm for taking up these leases, and many who did so forfeited their rental payments.

During the Federation drought, the snow belt became an extension of the “long paddock”, with graziers snapping up annual and special leases wherever feed was available. Larger players, like A.B. Triggs, manipulated the system by merging snow leases into “scrub leases” intended for less suitable country elsewhere — generous terms for the leaseholder, but less advantageous for the public estate.

It was also a period of poor land use, with large numbers of sheep and cattle grazing on land that could not withstand the impacts. Along with the rapid spread of rabbits, there were signs of severe erosion, not only in the alpine and sub-alpine regions but everywhere.

The need for snow lease reform was acknowledged. After 1910, no new scrub leases were issued; however, to avoid disadvantaging current leaseholders whose leases were due for renewal, they were converted into short-term permissive occupancies. These arrangements became quite popular in rougher country, which was only suitable for cattle, as the rents were very low.

By the 1920s, these practices were being phased out and replaced with low-cost, permissive occupancies on rougher cattle country. The 1924 survey of new snow leases, followed by the 1929 tender system, kept demand high; drought relief and pasture resting on the Monaro depended on them. Formal policies for the snow belt were often promised, but the Depression and WWII kept it in the “too hard” basket.

Erosion becomes the rallying cry

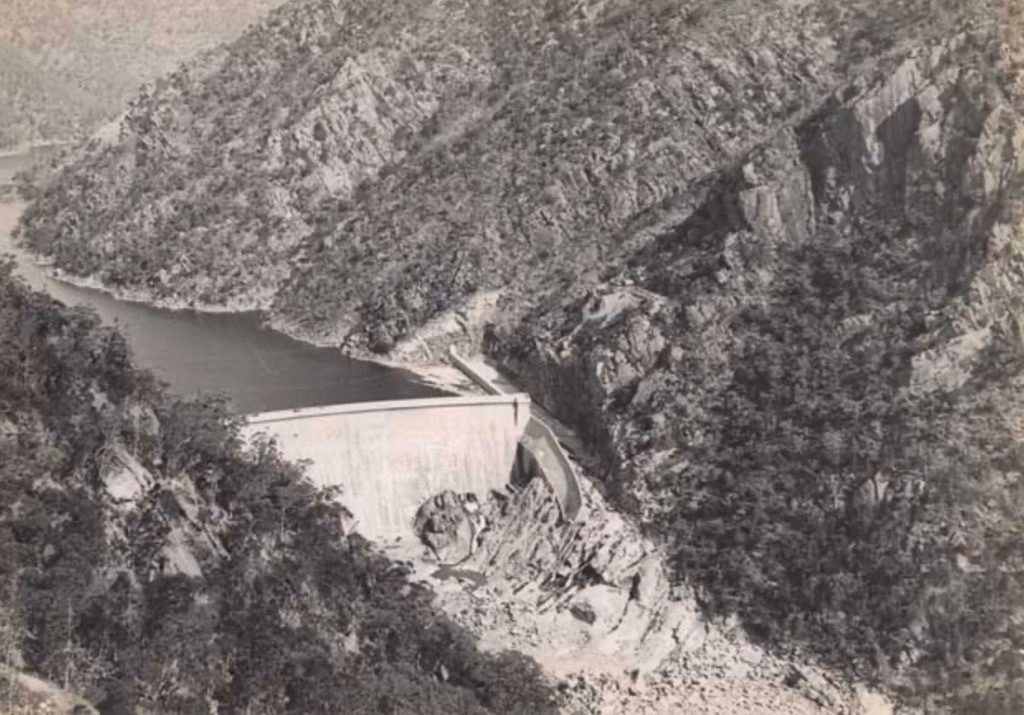

Soil erosion was hardly a new issue. It affected overstocked and rabbit-infested western districts from the 1880s onward. Catchment protection for the Snowies was first proposed in 1912 during the construction of Burrinjuck Dam. A total of 144,000 hectares around the headwaters of the Murrumbidgee and Tumut Rivers was set aside from sale. By the mid-1920s, the River Murray Commission voiced concerns about erosion on leased land in the upper Murray catchment.

In 1928, forester Charles Lane Poole, the Director of the Commonwealth Forestry Bureau, was concerned about the water yield for the new Hume Dam, which he discussed at the Empire Forestry Conference that year. He warned that “man and his stock” could cause long-term damage to the mountain catchments of the Murray River. There was no scientific evidence to support these claims; it was simply a common feeling at the time. However, there was some truth to the concerns, as grazier burns in steeper areas left those regions vulnerable to rain and melting snow.

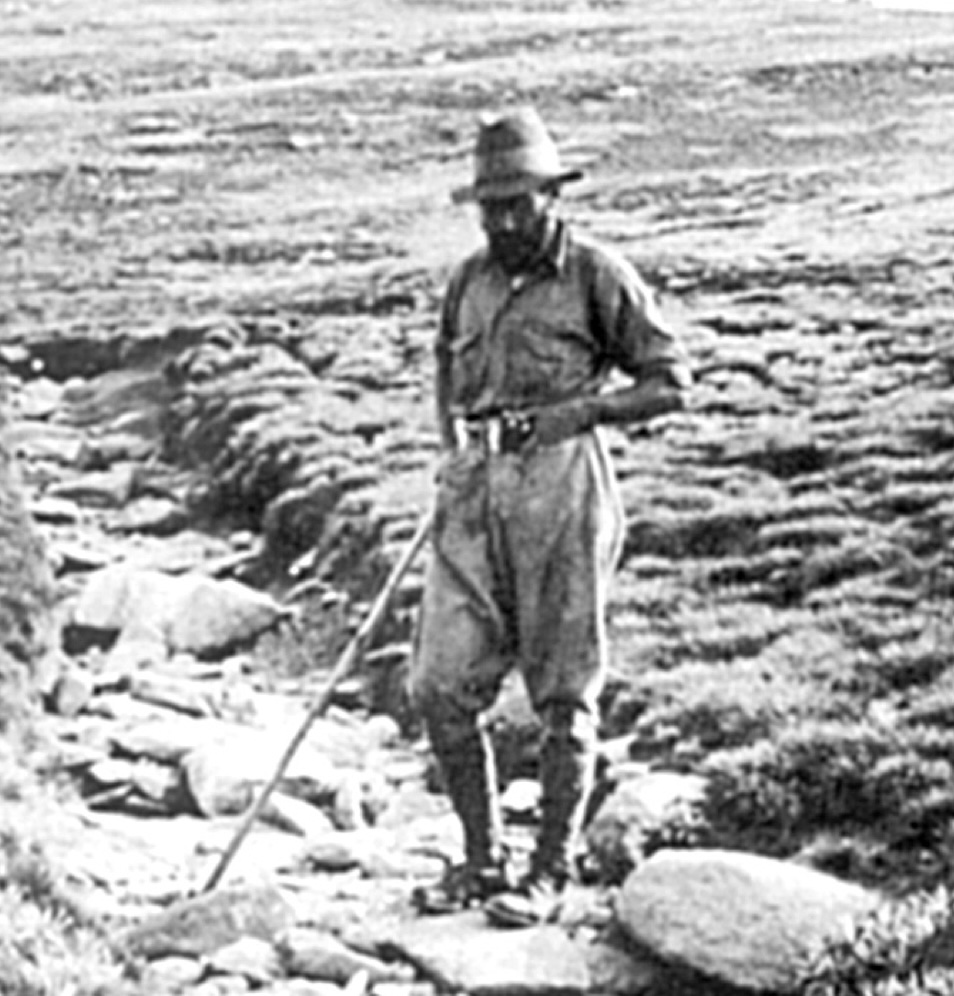

After securing funds during a depression, a young forester named Baldur Byles was awarded a scholarship to study abroad, focusing on erosion-affected areas in Mediterranean countries. Upon his return, he was directed to spend the summer of 1931-32 in the Snowy Mountains to investigate timber resources and soil erosion on the NSW part of the upper Murray catchment, particularly on the western slopes of the Snowy Mountains, where rain and snow were heaviest.

Baldur meticulously planned and carried out his survey of the area. He covered about 350,000 hectares from the Bago Plateau in the north to the Pilot in the south, travelling on a horse and a packhorse, which he left at base camps in the sub-alpine region.

His main focus was on alpine ash forests growing on deep soils on the steep middle slopes of the catchment, as well as the vegetative mosaics of bogs, shrubs, and herbfields. As a result, his report was not only a more detailed record of the unobserved and unmapped aspects of alpine forested vegetation, but he also expanded his observations to include the bogs, shrubs, and herb fields of the sub-alpine zone.

While his recordings and photographs showed early signs of soil instability, he did not document the apocalypse that others would later claim, finding no evidence of large-scale erosion in the alpine ash belt or the alpine wood scrub.

Baldur’s main argument focused on the loss of an “underlying bed of semi-decomposed organic matter” that protected the soil from rain and snow across more than two-thirds of the area. Baldur claimed that this organic matter came from dense scrub, which was sensitive to fire, was killed after severe fires, and did not coppice.

He was among the few still supporting the ongoing grazing in the high country, but with some changes to their current practices. However, he remained critical of mountain cattlemen, claiming that their knowledge of the grasslands they depended on was in a “very primitive state”.

Byles recognised that graziers’ autumn burning of snow grass to expose new growth in spring could, on steep ground, remove protection from rain and meltwater. But he also argued that understocking, not overstocking, posed a greater danger. He understood the importance of keeping land grazed, not only to support the primary industry that relied on the high country during droughts, but also because, in practical terms, removing cattlemen wouldn’t prevent fires, as they would still come from surrounding areas.

He believed that erosion control in the snow belt needed to start with better fire management. The main idea was that the stock would only eat the new spring shoots of the snow grass. If there was a lot of herbage left at the end of summer, they found it hard to reach the new growth the next spring, so stock owners burnt off as they left the snow belt in autumn. Many of the stockmen’s fires were allowed to spread to higher areas, destroying small trees and shrubs. It was argued that they also helped dry out boggy areas, speeding up runoff after rain or snow, which led to more erosion.

Byles recommended building firebreaks, appointing rangers to oversee burning off, and improving stock routes so graziers wouldn’t have to burn regrowth scrub to make them passable.

Certainly, the graziers were very adversarial in their responses to any criticism, insisting they didn’t need government regulation or restrictions on their land use, and asserting their right to use the land as they saw fit. It was this attitude that put them at odds with many people.

Byles’ pragmatic view that grazing could continue with better management was overshadowed by a growing preservationist lobby. These weren’t locals with deep knowledge of seasonal changes, but rather academics, bureaucrats, and bushwalkers whose visits were brief, their conclusions broad, and their methods untested.

No controlled experimental plots were ever established to separate the effects of grazing from other factors like fire, rabbits, frost, snowdrifts, or wind. In other words, this wasn’t done as scientifically as most would expect.

The political pincer closes

The Snowy Mountains have long been a popular destination for recreation. Starting in 1888, visitors could stay at accommodations near the Yarrangobilly Caves. Early tourists in the 1890s went skiing on the slopes at Kiandra, which then extended to other suitable sites on the main range. Trout fishing was also widely enjoyed, supported by a stocking program that began in the early 20th century around the Yarrangobilly, Snowy, and Goodradigbee Rivers. In 1906, about 25,000 hectares on either side of Mt Kosciuszko were set aside for public recreation and game preservation. A road to the summit of Mt Kosciuszko and a nearby hotel was built in 1909.

By the 1940s, the effort to conserve the Snowies for recreation and “pristine nature” was growing stronger. Figures like Miles Dunphy, who had previously successfully campaigned for a national park in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney, lobbied for a “primitive area” without grazing. In 1943, he was approached by the Lands Department to assist in drafting plans for a park reserve of some kind.

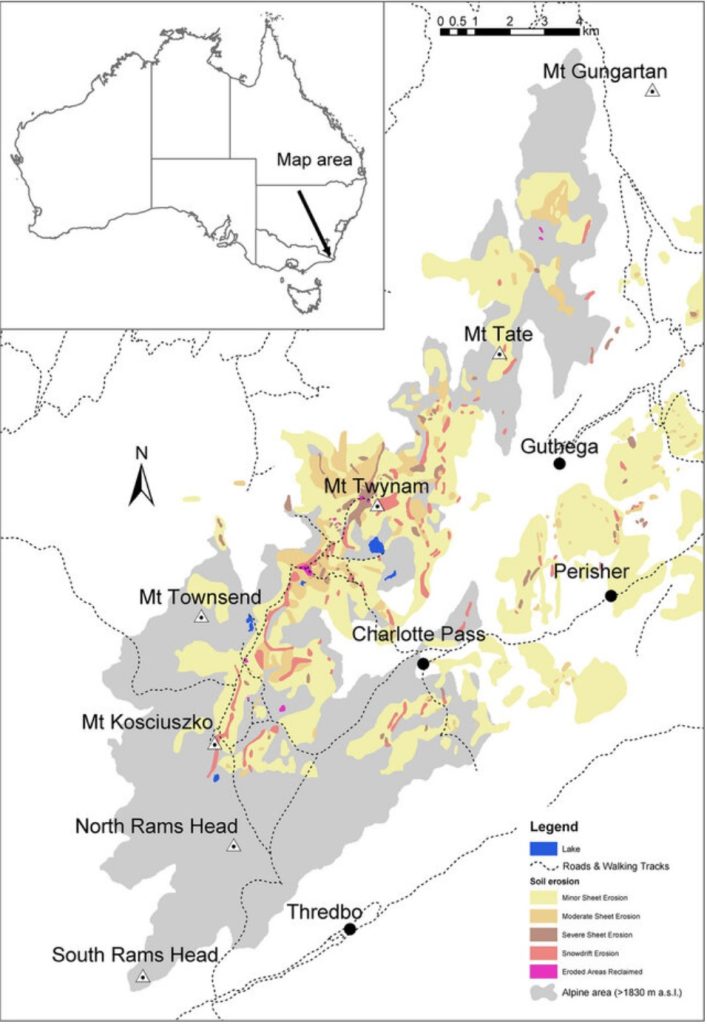

In 1944, Labor Premier William McKell declared the 541,600-hectare Kosciuszko State Park (KSP). It included all the state forests in the snow belt and former forestry resources such as the planting of exotic pines at Jounama in the 1920s, beautification trees, a nursery, and timber supplies for works, which became part of the new reserve. While the new park ensured free access and supported the development of recreation in the Snowy Mountains, its main aim was preservation and to enforce tighter control over seasonal grazing to address ongoing concerns about catchment management and soil erosion. Grazing continued but under stricter rules, leading to decades of conflict. It was removed from the Main Range and Rams Head Range areas in 1944 because of evidence of severe erosion. This first removal is probably the only one justified due to stock grazing.

The arrival of the Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Scheme in the late 1940s changed everything. The Snowy Mountains Hydro-Electric Authority’s (SMHEA) extensive earthworks tore through roads, tunnels, dams, and spoil heaps across the high country, leading to obvious erosion. Yet, its chair, William Hudson, was skilled at avoiding scrutiny by blaming mountain grazing as the main environmental villain. Scientists like William Browne and, later, Alec Costin, often funded by SMHEA itself, produced reports full of rhetoric and lacking solid experimental evidence. Rabbits, feral horses, fire history, and the Scheme’s own bulldozed slopes hardly received any mention. Grazing was made an easy scapegoat.

On one side, the argument was that the snow belt’s ongoing health depended on summer grazing, persistent efforts to control rabbits, and careful use of fire. Graziers claimed that the leading cause of erosion was rabbits eating the roots of white clover and snow grass, while mild fires helped to rejuvenate the pastures. Surveyor C. J. Harnett, appointed by the minister as his snow belt advisor, for example, as a young lad saw his father burn “wine bush” (Prosthanthera cuneata) areas on Mt Jagungal, which led to the creation of “fine grass country”. He argued that in other parts of the snow belt, where there was no burning, rabbits had caused wine bush infestations, and he sought the withdrawal of leases where leaseholders allowed rabbits to multiply.

On the other hand, there was an accusation that grazing and associated burning needed to be limited to protect the catchments. Grazier burning was described as an “improvident practice” where displaced soil was “carried into the creeks and rivers and entirely lost,” which caused serious erosion on the mountain slopes. Richard Helms, one of the aesthetic advocates who visited the Snowy Mountains in 1889, wrote in 1897 to the Royal Geographical Society:

What right had one section of the community, whether through ignorance or maybe greed, to deprive other people of the full enjoyment of the unsullied alpine landscape?

The preservation groups lobbied the government to set aside at least 10 per cent of the snow belt for preservation, free from any form of tenure or grazing use. The Linnaean Society called for a pristine area untouched by human influence at the high peaks, while Dunphy pressed for guaranteed public access for long-distance walkers. Scientists also sought to exclude tourists in the same way they aimed to exclude sheep.

The KSP Trust (managers of the KSP) had limited resources, even though it was responsible for balancing the interests of graziers, lower-catchment farmers, irrigators, scientists, recreational groups, and environmentalists. They made no progress in their first ten years, despite expectations from bushwalkers and scientists that at least ten per cent of the park be designated as a “primitive area.” A deadlock among the different factions on the Trust prevented any decisions from being made.

A clear stance emerged from the ongoing debate. Sheep should never be allowed in the mountains because their close grazing habits damage the soil, and there should be no grazing above the treeline, nor any fires anywhere. The main belief was that an area as vital and unique as the alpine country should remain as natural as possible to maintain a steady water supply in the lower catchments and for the Snowy-Hydro Scheme.

Geologists and biologists began inspecting different areas. In 1952, Browne, a well-known member of the Linnean Society, gave a lecture at Sydney University describing the Kosciuszko plateau as badly damaged by grazing, with bogs and fens destroyed. Tracks made by stock, selective grazing, and fires increased runoff and lowered the water table. He also criticised tourists and skiers, claiming that future access roads, hotels and lodges would cause even more damage.

By using hyperbole and exaggeration, Browne captured widespread attention by describing a scenario where, after 200-300 years of current practices causing ongoing erosion, the renowned landscape would shrink to rocky hills with stagnant pools along abandoned rivers.

The reality was that Browne knew the Snowy scheme wouldn’t be abandoned despite its effects, and there was no way the entire park would be reserved just for scientific research. It’s no surprise, then, that grazing was an easy target.

Alec Costin was another scientist similar to Browne. He is often regarded as a skilled and passionate alpine ecologist, initially working for the Soil Conservation Service and CSIRO. His early research involved identifying and describing alpine plant communities, but he later shifted his focus to the perceived preferential grazing of herbs in the alpine herb fields, which he argued led to the formation of inter-tussock spaces, along with compaction and erosion.

Costin finished his honours thesis, which resulted in the 1954 publication of A Study of the Ecosystems of the Monaro Region of New South Wales. This celebrated study is seen as an important work on mountain ecology, but its main conclusion—namely, the severe reduction of grazing and complete fire exclusion—was based on assumptions, overseas analogies and selective observations. Even his later experimental data showed that a grazed and burnt plot had much higher coverage of grass and herbs than its unburnt and ungrazed counterpart. His research also failed to consider the impacts of the rabbit plague, downplayed the SMHEA footprint, and dismissed graziers’ local knowledge as superstition. As with many similar disputes, the media accepted the academics’ perspective, portraying stockmen as relics clinging to “destructive” traditions.

This position revealed the limitations of Costin’s approach. His main strength was in describing and classifying the vegetation and soils of the alpine region, but when it came to assessing impacts, he went beyond careful description into interpretation. The lack of properly controlled experiments meant that his conclusions about grazing and fire were based more on inference than on rigorous testing, making them far less reliable than his descriptive work. The recent bushfires in 2003 and 2019-20 clearly confirmed that intense bushfires are a significant source of erosion that was insufficiently considered at the time.

He was leading a political campaign to end grazing in the snow belt. His work with the Alpine Ecology Unit was funded by SMHEA, eager to boost its environmental reputation, despite, in the words of Costin in his early years, “buggering up the country pretty well everywhere they went”. His outspoken opposition to grazing in the high country appealed to SMHEA, as it shifted focus away from its own mistakes and drew attention towards farmers allegedly causing “havoc on the mountains with their hard-hooved animals”.

During the 1950s, Costin and other activist ecologists worked hard not only to restrict the activities of the SMHEA but also launched a relentless campaign against the graziers. Costin reignited efforts to establish a Kosciuszko primitive area, preparing a submission signed by fifty scientists. They aimed to reserve areas not for their beauty but solely for scientific research.

There were major wildfires in 1951-2 that burned over 2.3 million acres across Victoria and NSW. Heavy rains and flooding after the fires caused increased erosion on exposed ground. At that time, the leading primary producers in the lower catchment, who relied on water from the Snowy Hydro Scheme, began protesting because they were concerned about the erosion issue and its impact on their water access. Hudson used this as an opportunity to rally that group to shift their focus away from criticising SMHEA erosion control efforts related to their large-scale development and instead concentrate on concerns about grazing on the high plains.

Following a major inspection of erosion damage organised by SMHEA in 1955, reports indicated that the Murray, Snowy, and Murrumbidgee catchments were already heavily eroded, and SMHEA’s activities had played a part in this erosion. However, most criticism focused on snow belt graziers and their alleged “over-grazing” and “deliberate firing,” which were said to “destroy much of the vegetation cover and the natural bogs.” Nonetheless, those on the inspection tour say they only saw two severely eroded areas during the five-day trip and found it difficult to see how overgrazing and fire were the primary causes of erosion.

Later that year, a Soil Conservation Service officer based in Tumut, J. C. Newman, demonstrated how “science” was practised at the time by criticising alpine grazing. He believed erosion had “not yet reached alarming proportions,” but he had observed enough “severely damaged areas” in both alpine and sub-alpine regions of the snow belt to decide that current stock management practices needed changing. He formed this opinion without doing any work to identify or rule out other potential causes, such as rabbits or natural erosive events. However, he thought that the “ideal answer” would be to develop:

An improved pasture…which will not require burning and yet will support stock at least as well as burnt snow grass,

but

Considerable research will be necessary before such a pasture becomes a reality.

Dr Max Mueller, a scientist recruited by SMHEA to lead its new scientific division, was called a “great scientist.” He told anyone willing to listen that grazing caused “irreparable damage” and that “one million tons of soil had already been lost,” without any supporting data. He was pleased to see grazing on the highest ranges replaced by recreation.

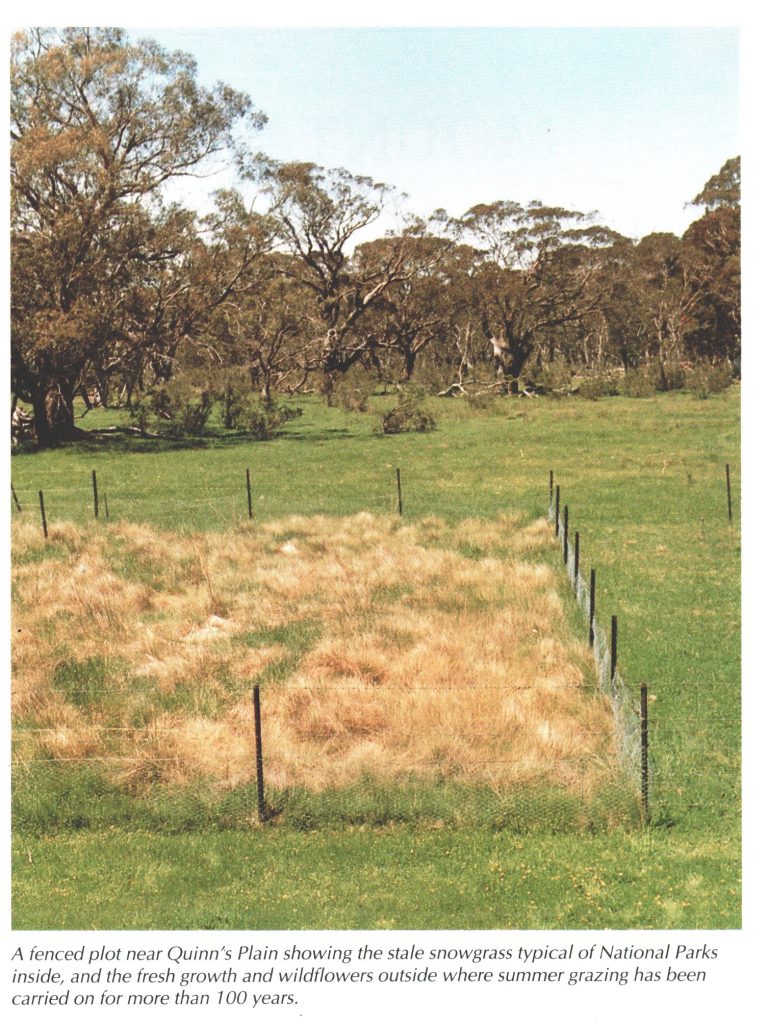

Conversely, and again without any replicated studies, the graziers, with their extensive knowledge of changes over many years, strongly argued that vegetative cover was denser than it had been in the early 1940s, and snow grass was allowed to grow dry and rank. Instead of promoting the utopian Garden of Eden envisioned by the so-called experts, graziers warned that declining soil fertility was a significant cause of erosion. They pointed out that steep areas damaged before the 1943 redistribution of snow belt leases were recovering, and burning off was now more regulated. They claimed that before the advent of SMHEA, no one had ever seen mud in a mountain stream. They argued that the scientists hadn’t been in the mountains long enough to understand what was happening. They also referred to the devastating fires of 1939 and 1951-2, which, along with rabbits, contributed to the erosion observed by many.

In fact, heavy rains in May 1939, totalling over 300 millimetres for the month, on bare soil left by bushfires, significantly increased erosion caused by frost-heave, where soil particles are loosened by needle-like ice sliding down slopes.

These practical men, who had watched the mountains for years, believed the scientists’ claims were misrepresentations or distortions of reality. They criticised the Soil Conservation Service, saying that while they had spent millions showing farmers across the state how to control erosion, the only support they offered to snow belt lessees was advice on how to get off the mountain.

The reality was that areas like Rules Point, which had supported large mobs of cattle since grazing began in the high country, were regarded as the “best areas in the district.” High winds and destructive wildfires were enough to cause erosion. At a meeting, the lessees acknowledged there were issues and aimed to support their case with facts that backed their position and practices. They agreed to pursue greater security of tenure to encourage changes to their leases; that a research station be established to help develop snow belt pastures; and that a governing body of “well-informed men” be set up to resolve problems.

However, the odds were stacked against them. After visiting the Snowy Mountains in mid-1956, new Minister for Conservation Ernest Wetherell asked for a report on the erosion issue, particularly regarding grazing. “All available evidence” was reviewed, and the report recommended protecting the snow belt area from erosion, which would mean stopping or heavily restricting stock use, starting from the end of all existing leases in June 1957.

The Australian Academy of Science was established in February 1954 mainly to promote unity among different scientific research centres across Australia. By 1957, they became involved in the alpine grazing debate, chiefly to justify their Commonwealth funding by enhancing their reputation and increasing their profile in environmental discussions and calls for new national parks. They were based in Canberra, close to CSIRO’s main offices and ANU. University House served as a gathering point for the anti-grazing coalition, where SMHEA, government officials, academics, and CSIRO staff met. In September 1956, the Academy agreed to examine the “progressive deterioration of the high country in the Kosciusko and north-east Victorian regions”.

Inaugural fellows of the Academy, Browne and John Turner, served on the investigative committee. They were joined by Ian Clunes Ross, head of CSIRO; microbiologist Frank Fenner from ANU; Costin; Robert Crocker, a professor of botany at the University of Sydney; and Dr John Evans of the Australian Museum. Their minds were closed to the causes of erosion, as a brief site inspection convinced them that grazing was the culprit, reinforcing the idea that their report was rushed to meet political needs. They recommended that all stock be excluded from catchment areas above 1,350 metres and that burning off be prohibited.

In the public eye, this was a strong endorsement of previous calls to limit grazing and burning. However, the report relied solely on academic opinions about catchment deterioration, presenting itself as science. A proposal to extend the tenure length was rejected, and not surprisingly, the suggestion of replacing snow grasses with improved pastures in the alpine areas was also dismissed. The mainstream newspapers all reported sympathetically on the environmental cause. It was recommended that the snow leases above 1,350 metres be withdrawn, justified by “years of research by officers of the Soil Conservation Service”.

The graziers saw this as hysteria over limited grazing. The unregulated grazing and burning in the early 20th century had not damaged the mountains, so the regulated grazing and burning weren’t a threat. There was even strong anecdotal evidence that controlled grazing helped native grasses. Another key point in their favour was the lessees’ full cooperation with fire prevention measures under the Hume-Snowy Bushfire Prevention District (HSBFPD).

The head of the Soil Conservation Service, Sam Clayton, and Byles, representing the KSP Trust, submitted comprehensive reports summarising ten years of “research” into grazing and burning impacts. However, their work lacked proper scientific data analysis and mainly criticised illegal grazing on previously withdrawn leases and areas restored by SMHEA, claiming that lessees could not be trusted and that all stock should be removed.

Byles’ work, in particular, strikes at the core of the issue. He made disparaging comments about the stockmen, such as they “had not been influenced or touched by scientific investigation” and “were loath to consider new ideas”. He concluded that:

Their stock of fundamental knowledge concerning the grasslands from which they get their living was practically nil.

However, in his thorough history of the fight against grazing in the Snowy Mountains, John Merritt notes that both accusations are false. For example, the graziers supported a vaccine for black disease, developed in the 1920s, which eradicated a century-long problem for snow belt flocks and was praised by the bacteriologists involved. The lessees in the early 1930s were attentive and inquisitive, and Byles relied heavily on observations from men who spent a long time in the snow belt, rather than on data from properly designed field experiments.

For his 1932 report, they educated him on the growth cycle of kangaroo grass and the drying of marshy ground.

Ultimately, however, in early 1958, the Cabinet approved the recommendation to withdraw snow leases above 1,350 metres. To give lessees time to adapt, it was decided to convert these leases to permissive occupancies, allowing grazing to continue until the end of April 1958. The Jindabyne Branch of the Labor Party warned early on that if the mountains were not grazed, they would soon face the threat of large, uncontrollable fires.

It is important to note that former politician and judge Sir Garfield Barwick, as a member of the KSP Trust, was unconvinced by the scientists’ and soil conservationists’ case against grazing. His highly perceptive legal mind could see through their shallow arguments because he believed, quite rightly, that he had not been presented with proof that grazing caused erosion. However, he did admit that grazing appeared to prevent eroded areas from recovering.

Aside from the arguments of SMHEA about accusations of a lack of patriotism and the need to act in the national interest to support their project, the snow belt lessees had a valid point that none of the scientists could disprove with reliable data before making their conclusions about grazing. For starters, the area around Mt Kosciuszko, which hadn’t been grazed for 14 years, was more degraded than ever; the plains near the former Currango Station, considered an erosion risk, were improving after a severe rabbit infestation in the 1930s and early 1940s; and the bare patches on the eastern slopes of several high peaks were caused by snow drifts that lingered well into summer, not grazing.

The graziers believed that the scientists overlooked the positive effects of grazing, such as maintaining healthy ground cover through the fertilising action of animal dung, as observed at Rules Point and Dead Horse Gap, and preventing the build-up of dried grass, which hindered spring re-growth and crowded out vital herb species.

The scientists were solely focused on grazing and failed to consider the effects of fire, snow drifts, wind, frost, and rabbits on erosion. They said anything to persuade the media, politicians and the public to support their position. For example, Professor Crocker from the Academy made an outrageous claim that areas around Mt Twynam and Mt Carruthers had lost “over 400,000 hectares of topsoil in 30 years due to stock grazing”. However, he obviously overlooked that those areas had been off-limits to grazing for 15 years. The Academy’s own document recommending a primitive area above Charlotte Pass, which included the two mountains, stated that it was:

In its original condition, practically untouched and undisturbed, just as it was left when the last glacier melted about 10,000 years ago.

They also overlooked erosion caused by the major earthmoving works of the SMHEA scheme or the erosion on farmland near the recently expanded Burrinjuck and Hume dams. Mountain stockmen argued they hadn’t seen any silt in mountain streams before SMHEA construction began. They should have set up controlled paired experiments in grazed and non-grazed areas to test different ideas about what caused the erosion.

These examples were clear to those who lived and worked in the snow belt. However, on 15 October 1958, the combined influence of political will, academic backing, and SMHEA support rendered the outcome unavoidable. The Labor caucus approved the ban on grazing above 1,350 metres. About 90 to 130 leases were affected. This decision was not based on repeated trials or conclusive cause-and-effect evidence but on a narrative designed to favour both the conservation lobby and the hydro-engineering giant. The fact that ungrazed areas experienced similar or worse degradation was quietly ignored.

It’s no surprise that a paper published in 2013 revealed that reviewed scientific work in the high country of south-eastern Australia supported my view that scientific research was often inadequate. The paper found that nearly 90 per cent of the studies lacked a clear hypothesis, had short durations, and the experimental designs were of poor quality, with only half having replicated treatments, and a third with none. The rest provide no details on their experimental setup. Of the models presented with some detail on the data used, very few relied on replicated data, instead depending on a single site. Consequently, the models were neither sound nor robust.

From scapegoating to mismanagement: the NPWS era

The grazing ban was cheered in Sydney lecture theatres and bushwalking clubs, but it signalled a turning point for the alpine landscape, and not in the way its supporters hoped. Scientists and policymakers who had persuaded the government to “save” the mountains by removing cattle and fire now had their opportunity to test their theory. What followed wasn’t ecological recovery, but the slow replacement of short, productive pastures with thick, rank grass and dense shrub regrowth. Perfect fuel for the inevitable mega fires that later swept through.

The KSP Trust, already hamstrung by factional bickering, was dissolved in 1967 when the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) was established. NPWS inherited a park with a century of practical knowledge wiped out, along with the stockmen. The old burning patterns of autumn fires that removed thatch, encouraged spring growth and created green firebreaks were no longer practised. Fire became a dirty word in management circles, and the prevailing belief was that excluding people, livestock, and flame would allow “nature to heal itself.”

The problem with “letting nature heal” in a fire-prone area is that nature’s solution often involves a severe fire. Without grazing, snow grass grew tall and tangled. Without regular cool burns, shrub species like tea-tree and wine bush spread, creating dense, woody thickets. The same agencies that criticised graziers’ “indiscriminate burning” now managed a regime where fuel loads were higher, drier and more continuous than ever.

By the mid-1970s, park rangers confronted fuel conditions that seasoned cattlemen would have recognised as dangerous. Yet NPWS policy remained rooted in the belief that human interference was the original sin and that any form of deliberate burning risked “damaging the ecosystem.” A token hazard reduction program was rolled out, but it scarcely made a dent in the scale of the problem. What had once been a patchwork of grazed clearings, open frost hollows and burnt firebreaks had become a continuous carpet of fuel spanning the alpine and sub-alpine zones.

Within a decade of NPWS management, impenetrable scrub, high fire hazard, noxious weeds and destructive erosion became the dominant features of the park for those venturing off the beaten track. Native flowers, grasses, and wildlife were disappearing as shrubs, feral pigs and deer encroached. Rather than a “wilderness” in ecological terms, the park quickly transformed into a wasteland of desolation. Tragically, worse was yet to come this century.

Gone were the days when the region was filled with sheep and cattle in the late 1880s, when scientist Dr von Ledenfeld enthusiastically described the Kosciuszko region:

The upper regions of up to 7,100 feet are covered with rich verdure; beautiful, soft grass growing a foot high, enough for five sheep to the acre in summer. Numerous sweet alpine herbs grow among the grass. The whole is a most beautiful pasture land.

The warnings were clear. In 1965, even before NPWS was established, a significant fire near Talbingo swept through the northern section of the park, halted only where active grazing and resident stockmen reduced fuel and provided immediate suppression. In subsequent years, lightning strikes that might have previously fizzled out in short grass began spreading unchecked through long, dry fuels.

By the 1990s, NPWS had perfected the art of firefighting theatrics. There were helicopter water drops, distant command posts, and press releases praising “ecological burns” after the event. On the ground, the reality was that large fires had become routine, and the damage from these high-intensity events was far worse for soil stability and alpine bog recovery than any amount of regulated grazing ever was. The same academics who had campaigned to end grazing now wrote papers on “post-fire erosion” without ever admitting that the fuel build-up their policies caused was part of the reason.

Meanwhile, NPWS intensified its focus on the recreation agenda — including ski resorts, sealed roads, and year-round tourism infrastructure. The very impacts Browne and Costin claimed would cause erosion were now managed under a “visitor experience” banner. Bulldozers and graders carved new runs, expanded carparks, and moved soil in ways no cow ever could. Still, the old scapegoat of grazing remained a common mention in official histories as the cause of all previous problems.

In short, the NPWS inherited a landscape from which they had removed the most experienced land managers, banned the primary tool for reducing grass fuel, and then sat back under the illusion that doing less was doing better. The ecological outcome was a fuel-heavy, fire-prone country that burned hotter, more often, longer and with greater soil loss than during the grazing era.

The era of big fires

Aborigines were long-term residents of the Monaro region. It was widely known that they gathered in the alpine areas to feast on the bogong moth and perform various ceremonies. Not much is known about their burning practices, but clues can be found in the land inherited by Europeans after their populations declined, and their land management stopped.

Although some academics and writers minimised Aboriginal burning in the alpine region, early settlers observed no large areas regrowing after high-intensity fires in the alpine woodlands, indicating that fuel loads were probably never allowed to build up.

Although there were issues with shrub invasion, graziers were blamed without any data to support it. No one, except the stockmen, considered that the shrubs were spreading unchecked due to fire exclusion, which only increased the risks to the catchments.

The Bush Fire Prevention Associations in NSW began with the establishment of the HSBFPD in 1952, shortly after the Snowy-Hydro scheme was launched. Partly in response to the devastating fires of 1904, 1926 and 1939, there was also concern for the safety of workers in remote and rugged areas, marking the first major influx of people to the region since the gold rush era of the 1860s. The need for effective fire protection was critical. The scheme’s first fire management plan recognised that wildfire could be managed in fuel-reduced zones, even though complete fire protection remained nearly impossible. After 60 wildfires burned approximately 50,000 hectares in 1951-52, only 8,000 hectares were affected in 1953-54 from 24 fires.

Over the next decade, there were few wildfires in areas where prescribed burning was effective, although some criticism arose when some burns became too hot and caused unnecessary damage.

The fire that swept out of Talbingo in March 1965 should have been the first warning sign. Stockmen and lessees at the time knew exactly why some runs survived and others didn’t — short grass, green firebreaks, and men on the ground who treated every puff of smoke as their problem. The areas that were saved were still being grazed. The areas that were lost had no one watching, no fuel management, and plenty of dry feed to burn. It was a simple equation the cattlemen understood, but which the new class of park managers seemed determined to ignore.

Despite the area’s designation as a national park in late 1967, the HSBFPD commenced aerial prescribed burning in Kosciuszko National Park. A trial aerial burn covering 5,000 hectares in April 1968 proved successful and was included in fire management plans. It represented the best opportunity for effective and acceptable fuel management within a preservation-focused approach.

After the 1968 wildfires, which burned more of the park, Alan McArthur, as part of his influential research into fire behaviour, questioned whether the fire protection measures were adequate, as fuel reduction was only carried out along roads and fire trails.

The 1972-73 fire season was particularly severe, with lightning storms igniting numerous fires under extreme fire weather conditions. Forty-nine fires burned 48,000 hectares in Kosciuszko National Park. Although there was no damage to assets, it caused significant harm to catchments. Unfortunately, over the next decade, very little effective fuel management burning was carried out as planned prescribed burns were curtailed. NPWS argued for considerably less burning, claiming that “all species in the park are adapted to high intensity fire” and that prescribed burning was “a serious concern”.

In 1982, NPWS used legal reasons to withdraw from the 30-year cooperative scheme, leading to the disbandment of the HSBFPD.

After grazing was banned above 1,350 metres and gradually scaled back elsewhere in the park, the fire regime shifted. Lightning strikes that once would have smouldered through sparse fuels now ignited into fast-moving fires, crowning through shrubs and scorching alpine bogs. The old cattlemen’s burns were controlled and seasonal, low-intensity autumn fires that slowly spread across the landscape and reduced fuel without harming the soil. NPWS replaced them with minimal burning until the preventable summer infernos arrived.

Big fires occurred in 1978, 1983 and 1988, leading to severe and increased soil erosion. It was clearly evident that extensive wildfires were a major cause of unacceptable damage to the soil.

Another aspect was NPWS allowing wildfires to be left unattended or undetected, despite the success of developing rapid and direct initial attack response in other parts of the state. The contrast with the neighbouring forestry districts at Tumut, Batlow and Tumbarumba, with their valuable pine plantations, was stark. Forestry quickly extinguished lightning strikes on their land with minimal damage, but the strikes on the Kosciuszko National Park were allowed to burn indefinitely, causing catastrophic damage.

The 2003 Alpine Fires clearly showed the failure of that policy. Lightning storms in January ignited multiple fires in Kosciuszko and nearby parks. After years of accumulated fuel, these fires merged into a single front that burned for weeks, consuming more than half the park and over 1.73 million hectares overall. In contrast, several lightning strikes also hit state forests and private lands to the west of the park at the same time, causing minimal damage, and all were controlled within three days.

Within Kosciuszko National Park, temperatures in the burn zones were so extreme that alpine ash forests were completely destroyed, prompting reseeding from external sources. Sensitive peat bogs were scorched down to the mineral layer, releasing carbon and damaging the sponge-like structure that regulates water flow into the Murray, Murrumbidgee, and Snowy rivers. Soil erosion after the fire was far worse than any issues alleged against the graziers during their worst years.

Unfortunately, this was not an isolated event. Fires in 2006–07 and during the Black Summer of 2019–20 all followed the same pattern. They were large fires that lasted a long time. Ignitions from lightning or accidents, during the grazing era, would have been quickly contained. However, in the post-grazing era, heavy, continuous fuels formed a ladder from the ground to the canopy; fire intensities were high enough to destroy seed banks and sterilise soils; and there was widespread post-fire erosion as bare ground was battered by alpine rain and snowmelt.

The 2003 and 2019–20 fires exposed the real impact of the NPWS approach to fire management, which was to “lock it up and let it burn.” In 2019/20, almost a third of the park, including high-country areas that hadn’t seen such intense fires in living memory, was burnt. Critical habitat for native species was destroyed within days. The official stance was that “climate change” was to blame, but this conveniently ignored how decades of fuel buildup under NPWS policies had turned the park into a powder keg waiting for a spark. These fires caused extensive and severe damage to soil stability across a large area, much bigger than the grazing areas under the snow leases and permissive occupancies.

Furthermore, the fires tend to jump over park boundaries. When Kosciuszko ignites, it fuels the surrounding forests and farmland, causing damage to communities that have no control over NPWS management. The same neighbours who once grazed the high plains and helped manage fires now find themselves defending their own land from blazes starting in so-called “protected” areas.

It is worth questioning if the old grazing regime, with its patchwork of eaten-out firebreaks and low-intensity burns, was still in place; would these fires have spread as far or burned as intensely? The evidence from the 1965 Talbingo, the 2003 and the 2019-20 wildfires suggests no. The same applies to every instance where a grazed block or roadside has slowed a modern fire’s progress. The lesson is clear, but NPWS and the academics whose theories contributed to the problem tend to overlook it.

In summary, the post-grazing period has resulted in the opposite of what was promised. Instead of stable catchments and “natural” recovery, there is now a landscape prone to periodic destruction on a scale greater than what the stockmen ever achieved, followed by erosion events that undo decades of careful soil conservation downstream. The graziers were unfairly blamed for erosion they didn’t cause; NPWS has overseen erosion on a much larger scale and they call it a “natural process”.

Conclusion –ongoing management by neglect and inaction

The history of Kosciuszko National Park’s management illustrates how political motives, masked as science, can mislead environmental policy. Since the 1940s, grazing in the high country has been blamed for every patch of bare soil, declining bog, and muddy trickle. These claims were made by scientists, activists and bureaucrats who rarely stayed long enough to see a season change, let alone measure the many factors affecting alpine landscapes. There were no paired plots, no long-term controls, and no consideration for rabbits, snow drifts, frost heave, wind scour, or, most importantly, planned fire or wildfire.

The reality was that erosion was only severe in a limited three-kilometre section of the Main Range between Carruthers Peak and the eastern face of Mt Twynam – a very steep and exposed area.

SMHEA, with its extensive earthworks tearing through catchments, found a perfect distraction in this story. By funding and promoting anti-grazing research, they diverted attention from their own erosion issues and focused it on the stockmen. The outcome was a policy designed to benefit the preservation lobby and hydro engineers, not the land itself.

When grazing was banned above 1,350 metres in 1958, the government congratulated itself for “saving” the mountains. In reality, it had removed the people who knew the country best, stripped away the low-intensity fire regime that kept fuels manageable, and left the park to an agency whose guiding philosophy was that doing nothing was the highest form of management.

The decades since have revealed the folly of that thinking. Without grazing or planned burns, the high country has turned into a tinderbox. When wildfire occurs, as it inevitably does, it burns hotter, over larger areas, and with more lasting damage than the patchwork burns and grazed clearings of the past ever caused. Erosion, once the rallying cry against stockmen, now results in catastrophic amounts from post-fire runoff from sterilised soils.

The official account remains unchanged. Grazing was blamed, and its removal celebrated. This highlights how a simple slogan can overshadow the complex reality. In truth, mountain catchments were never actually “saved”; they became more vulnerable, and the downstream impacts are still visible in soil loss, reduced water quality and damaged habitats.

If the goal is to look after Kosciuszko’s alpine environment and protect the catchments, then we need to be honest about what works and what doesn’t. That means moving beyond the easy climate change excuse and the dogma that has trapped us in this cycle of fuel build-up and mega-fires, and taking seriously the knowledge and methods of those who managed the land before it became a political trophy.

Anything less is just repeating the same mistakes and expecting a different result, and the mountains won’t wait for us to learn.

Retired forestry and environmental manager John O’Donnell reviewed the state of the New South Wales Alps five years after the 2019-20 fires, which is a worthwhile read.

An absolutely BRILLIANT article. This brings together all the pieces of history, explaining what happened, how it happened, and how today this ‘unscientific’ history is repeating itself in relation to the brumby argument.

These pieces have been hidden for so long (unless people bother to read Hancock et al), but they are still often spoken about by our old-time graziers, who are left and whose memories and knowledge should be revered.

Can you believe that it was not long after the cattle were removed from the lower areas that we were also prohibited from horse riding in these same areas, under the guise that it’s now called wilderness? I.e. the whole southern end of the park and lower Snowy (my backyard and family’s 180 year domain).

Today, we deal with the brumby conspiracy.

Thank you for such an insightful piece and for your inspiration.

A very complex issue which would benefit from comments by the likes of Alec Costin but he has gone to another place. I am glad we have been able to preserve many of the huts built by miners and stockmen. I too am alarmed at the current frequency of wild fires.

It’s the same story for high plains in Tasmania. NPWS have had trouble coping with overgrown natural grasslands in Cradle Mountain National Park. These areas were so overgrown, they couldn’t even get a fire started with added fuel. Of course in extreme fire weather conditions these areas became “bombs”. In contrast a large private property on the other side of the road, which has been grazed and prescribe burned continuously for a century has much richer plant communities and supports native animals. The property was purchased a decade ago by Tasmanian Land Conservancy, who at the time, agreed to continue grazing through a lease arrangement with the previous owner and to continue regular burning. The 2019 fires around Miena were out of control, with the exclusion of sheep grazing and no prescribed burning for two decades, seen as a major contributor to increased fuel loads.

Tom Taylor from Currango had fights during the 1950s and 60’s, highlighting the flawed science. He predicted exactly what has transpired in the KNP. Nobody listened to the locals then, and they still aren’t listening to those who have the generational knowledge.

I wish the so-called academics and Greens of today would read this and, more importantly, acknowledge the sensibility and truth in the article.

Very, very inspiring, articulate story.

Thank you.