Life on Fraser Island was very isolated and lonely before access improved with combustion engines, regular flights, and ferries to transport cars and trucks. Communication was only by boat, telephone, radio, and aeroplane. In the case of accidents, help was six hours away by boat in Maryborough.

The age of telegraphy

The first breakthroughs in communication came with the spread of telegraph technology. Invented in the early 19th century, the electric telegraph allowed near-instantaneous transmission of coded messages over wires using Morse code, a system of dots and dashes. It revolutionised long-distance communication, replacing the need for messengers, ships, or semaphore signals.

But it was not a technology to be taken lightly. Telegraph systems required skilled operators, extensive infrastructure, and constant maintenance in remote and challenging terrain.

The first telegraph station in the area was established on nearby Woody Island. In the late 1860s, two lighthouses were constructed on the small island at either end to assist ships navigating into the Great Sandy Strait and then to the port of Maryborough. There were also lead lights to guide vessels to the mouth of the Mary River.

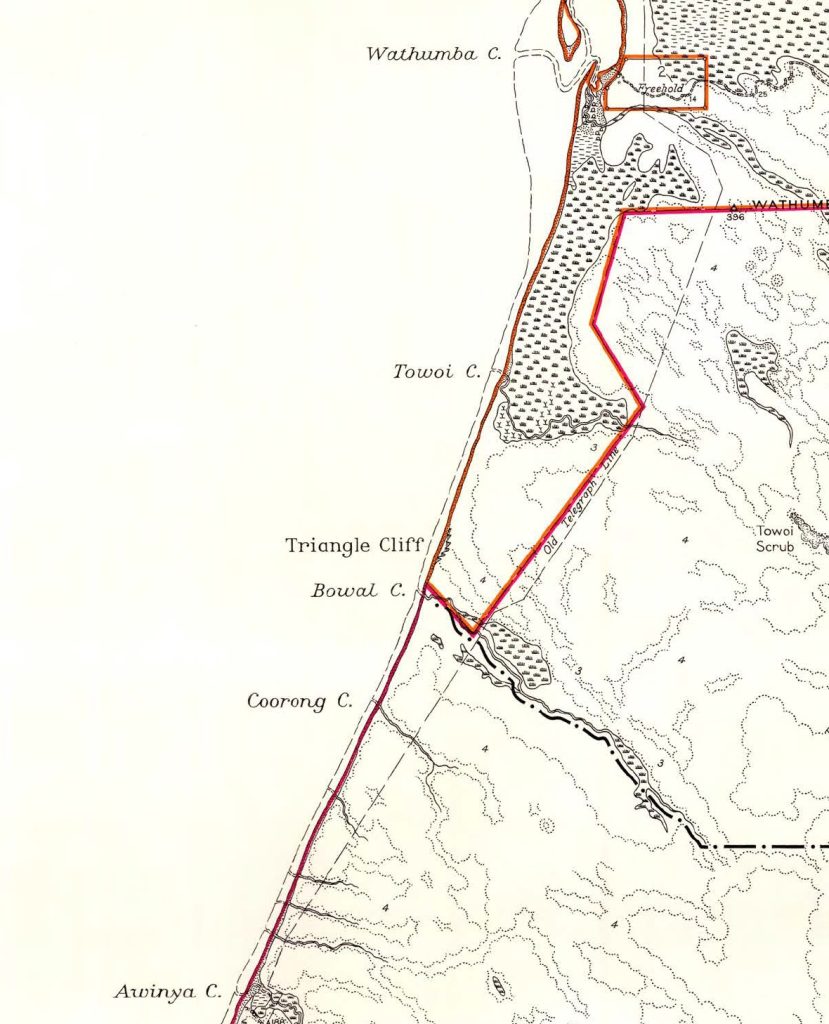

To support their communication needs for reporting ships passing through to Maryborough, a 25-mile extension was added to the telegraph line from Maryborough to Dayman Point at Urangan in 1868. Two years later, a submarine cable was laid three and a half miles to Woody Island, and a telegraph line ran along the island’s western side for 2¾ miles to the northern lighthouse. By that time, telegraphy had already transformed port operations, providing ship arrival times in advance and enhancing quarantine and customs responses.

While the first permanent European settlement on Fraser Island was the most remote, located near the northern tip at the Sandy Cape Lighthouse, the urgent need for communication with the mainland, especially the port of Maryborough, was driven by the establishment of the Quarantine Station. The station was built to process migrants arriving directly from overseas, primarily from Great Britain, as well as the thousands of South Pacific Islanders brought over to work on the sugar cane farms.

In 1884, a submarine cable was laid from Woody Island across the Great Sandy Strait to Bogimbah on Fraser Island, and then south to the Quarantine Station at North White Cliffs, where a telegraph office was established. It was regarded as an excellent lookout station overseeing the strait towards the mouth of the Mary River. The underwater cable was likely armoured with iron or steel wire and sheathed in gutta-percha — an early form of natural latex insulation harvested from tropical trees.

Meanwhile, the Sandy Cape Lighthouse accommodated a head lightkeeper, three assistant lightkeepers, their families, and a schoolteacher, making up a small community of around 40 people, including schoolchildren.

Communication between the lighthouse and the mainland needed to be maintained. At the time, it was believed that the isolated lighthouses along the coastline were vital points of observation, whose importance would grow during wartime.

In 1885, the Queensland Cabinet approved a telegraph line from the Quarantine Station to Sandy Cape. The Telegraph Department constructed a cottage near the shore where the cable landed at Bogimbah to accommodate the officer responsible for maintaining the telegraph line in both directions on the island.

The first resident line keeper, Patrick Searey, a former timber cutter on the island, was in charge of regular line patrols on horseback to make sure the line was maintained and kept functional. He would also deliver the mail to the lighthouse, usually along the western beach. He had to wait at Coongul Creek for low tide because he didn’t want to swim the horses across the narrow but deep creek – it was known as a shark nursery!

After the Quarantine Station closed in 1886, the telegraph line to it quickly deteriorated due to neglect. By the early 1900s, it was so rotten that it couldn’t be picked up without breaking.

In 1890, local dugong fisher Johann Heinrich (Harry) Bellert took over from Searey as the resident line keeper. He moved his young family to live at Bogimbah. During their time living at Bogimbah, three generations of the family (Harry, son Hans and grandson Keith) planted a mango tree each, and all of them are still there. The site became known as Bellert’s hut and is marked on modern maps as such.

The telephone era begins

By the early 1900s, telephone technology began replacing the telegraph. While still basic compared to today’s standards, the early telephone was a marvel. It worked by converting sound into electrical signals that could travel along a line and be converted back into sound at the other end. However, clarity was often poor, and long-distance calls required heavy-duty lines and constant amplification. Party lines were common, with multiple users sharing the same line, and privacy was almost non-existent.

In 1902, the Queensland government accepted a tender for an undersea telephone cable and overland line from Hervey Bay to Sandy Bay lighthouse. It ran from Urangan to Woody Island, then along the eastern side of the island to Jeffries Landing. From there, it was laid across the Great Sandy Strait to Bogimbah Creek. The work included erecting new test houses at the points where the cables landed and departed.

To support the new system, Ned Armitage landed between 800 and 1,000 iron poles on Fraser Island using his punt, Geraldine, to replace the original timber ones for the overhead telephone line. The line featured seven copper wires, each insulated in gutta-percha, then sheathed in galvanised wire and finished with a protective wrap of iron wire and tarred hemp, providing resistance to weather, termites, and salt corrosion.

The Deputy Postmaster General advised Maryborough telephone exchange subscribers that they could now use the new telephone line and pay per call. Woody Island and Bogimba were charged 10 pence for the first three minutes and sixpence for each additional three minutes. Calls to and from Sandy Cape cost one shilling sixpence for the first three minutes and one shilling for each extra three minutes. It was a hefty fee at the time, indicating the value and rarity of such communication.

While Bellert left the island or went on extended dugong hunting expeditions, Badjala men Ike Owens and his brother Banjo, along with the McLivers, helped clear the telephone line of suckers and other plant growth that could short the line or bring it down.

In 1914, Bellert brought the island’s first vehicle, a Model T Ford, to assist with his patrols. The family affectionately named the car “Leapin Lena.” Considering the terrain and the vehicle’s rudimentary build, its ability to stay operational was a miracle.

The telephone line stayed in service until World War II, when a dragging anchor broke it. Sadly, little evidence of it remains today, though many people report seeing the odd iron pole.

Postwar communications

In 1945, wireless radio communication was introduced to the island. Forestry’s headquarters at Central Station was located in the heart of the dense commercial forest. Radio and telephone communication was patchy, and in 1959, the headquarters was moved to the more accessible west coast site at Ungowa.

Forestry maintained a series of telephone lines to connect its scattered camps, with logging contractors often running their own extensions to their camps. However, the system was primitive, offering no guarantee of an immediate connection. If an accident occurred late in the day, it might not be reported until the following morning.

The tragic death of forestry worker Laurie Postans in January 1963 sparked urgent demands from both the forestry and timber industries to enhance communication. The outcome was the installation of a new telephone cable from Boonooroo across the Great Sandy Strait to a landing point south of Figtree Creek, then routed up the island via a telephone pole line to Ungowa.

This was soon followed by the introduction of radio telephones — still noisy and unreliable, but a significant improvement over previous methods. The PMG even installed a wind-powered generator on a pole at Ungowa Camp to keep the new communication equipment operational.

The story of early communications on Fraser Island is one of persistence, ingenuity, and necessity. From the clunky dots and dashes of the telegraph to the crackling voices over fragile telephone lines and finally to the hum of radio waves, every advance brought the island closer to the mainland.

Keeping a direct and immediate link to the outside world was never a luxury for those living and working in remote camps, lighthouses, or forestry outposts. It was their lifeline. Communication helped bridge the vastness of the separation in a place surrounded by sea and sand, where danger could be just one misstep away and help hours away. That connection meant everything.

Robert, I thought I saw somewhere that you have published a whole book on Fraser Island (at least as regards its forestry history).

I have been too busy reading other books from my home library, but I am nearing the end of these (just three books left), so let me know the status of your book, please.

Allan J.

When Sid began to develop Eurong, he had no communication and Telecom refused his request for a phone line. He solved the problem by stringing his own line of secondhand fencing wire through the forest to the Forestry exchange at Central Station and connecting it to an old fashioned wind up phone in his house at Eurong. Just two days after he found it worked the terrible accident of Jack Reville’s bus occurred. Sid, who was driving an overload of Jack’s passengers, raced back to Central Station and rang Eurong, asking his workers to go to the accident scene in as many vehicles as they had, with blankets and doors for stretchers. This was of immense use in the rescue effort.

As it aged, the fencing wire line deteriorated and it got harder to get calls through, so Sid attached an electric drill to the phone handle to wind it up faster.

It was the introduction of the Fraser Venture barge that enabled Telecom to introduce automatic telephones to the island. It was the first vessel big enough to carry all the steel word for four huge towers to be built on hills on the island and the four huts full of equipment needed. Getting the huts on trucks ashore in places like Wathumba Creek was a nightmare, as was cutting tracks through the forest to the hill tops.

Thanks, Angela. Great bit of information to add to the story.

Wow, what a history! Would anyone know the name of the man who had a forearm amputated and had a house on the southern mouth of the creek?

My family got to know him when my father was among the Officers of the 47th Battalion who arranged a bivouac there in Easter 1952. Nelson and I ran around the troops collecting bullet cartridges. A great weekend.

Geoff Raebel

Hi Geoff. Interesting question. I am not sure which creek you are referring to. I can’t help you, but hopefully another reader can.

All the best.

Robert

Having visited the island many times and touring around most of it, I can imagine how difficult it must have been to get and have communication on the island in those early days. Amazing, thank you again, Robert, for an interesting read. Janet

I lived in a caravan at the eastern end of Central Station for approximately 18 months, from March 1979, while undertaking forest research with the University of New England in NSW. I sometimes used the old wire party line that Angela said Sid erected. I recall on a few occasions that while I was calling the University, Sid would get on the ‘party line’ and tell me to ‘get off’ or words to that effect. He would also stop and berate me for not mending the line when it was broken following a storm or high winds, when branches or trees were brought down, breaking the wire.