In the years leading up to Queensland’s separation from New South Wales in 1859, the political mood across the continent’s northern reaches was restless yet hopeful. From the sunbaked cattle runs of the Darling Downs to the pine-timbered ridges around Moreton Bay, there was a low murmur that grew louder. Why should decisions for the north be made from distant Sydney? Brisbane was teeming with free settlers, and the penal past of Moreton Bay was being buried beneath the aspirations of farmers, merchants, and surveyors determined to chart their own course.

It was a time of frontier optimism, but also of ever-present danger. The new colony-to-be had over 7,000 kilometres of coastline, much of it wild, treacherous, and largely unlit. Ships bringing goods, settlers, and news from the world risked threading through coral shoals, sandbars, and wind-lashed headlands without any guidance. There was little room for error and no second chances in places like Breaksea Spit or the Wide Bay bar.

As Queensland began its own tentative steps as a new colony, it began erecting physical beacons to match. Lighthouses were tools of safety and potent symbols of sovereignty. Queensland’s only lighthouse was built before separation at Cape Moreton. Others soon followed at Bustard Head, Sandy Cape and Double Island Point.

Towering over the remote northern tip of Fraser Island, Sandy Cape Lighthouse became one of the most vital beacons in Queensland’s expanding coastal network. Built in 1870, it warned mariners of the notorious shoals that had claimed countless vessels. It also conveyed a message that Queensland was no longer a distant district of Sydney, but a self-governing colony in its own right, casting its light into the future.

And so begins the story of one such beacon—the Sandy Cape Lighthouse—and the brave souls who built, manned, and watched its flame stretch across both storm and time.

Recognising the pressing need to illuminate Queensland’s coasts, the new government appointed Commander George Poynter Heath as Portmaster in 1862 and passed the Marine Board Act that same year. However, funding remained tight, and initial efforts focused on managing harbour lights and pilot services.

By May 1864, a Select Committee had been appointed to inquire into the state of the colony’s rivers and harbours, eventually expanding its mandate to include lighthouses. A second Select Committee followed shortly after, examining Queensland’s booming trade and shipping needs. Both committees agreed emphatically that a lighthouse at Sandy Cape was essential. One report called it:

The site form its position and elevation the most eligible for erecting a lighthouse and from which a powerful dioptic light would command the danger.

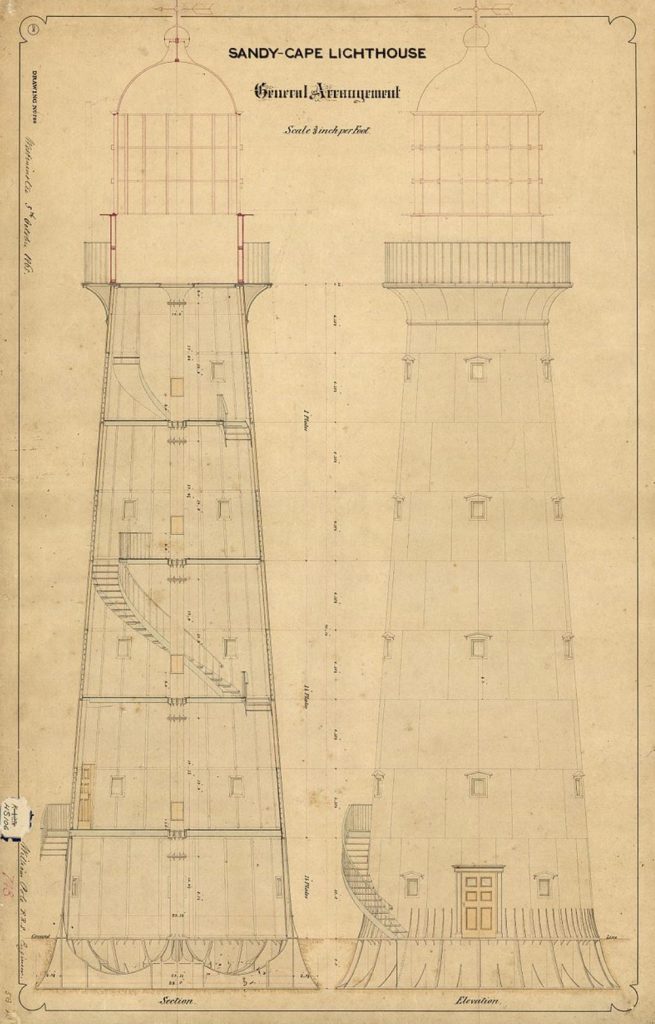

The construction plans for the lighthouse were prioritised. William Pole of Kitson and Company in England was assigned the task of designing the lighthouse. The result was a 99-foot (30-meter) tower, cast in sections in England by Hennett, Spinks and Co. Each cast-iron plate was flanged and could be bolted together like a giant Meccano set — a marvel of Victorian prefabrication.

Sandy Cape was one of only a few cast-iron lighthouses in Queensland. Cast iron was used because it could be fabricated in sections, shipped relatively easily and bolted together onsite, perfect for a remote location.

Despite the urgency, bureaucratic wheels turned slowly. Tenders didn’t close until 1868, and Maryborough builders John and Jacob Rooney secured the contract. Each tower segment was shipped to Maryborough, loaded aboard the schooner Resolute, and sailed just offshore, within 500 metres off Panama Point, which was later renamed Rooney Point.

A light raised from sand

Constructing the Sandy Cape Lighthouse was no small feat. It required bush ingenuity, grit, and determination in one of the colony’s most remote and unforgiving corners.

Sandy Cape was chosen at the island’s northern tip for its commanding view over Breaksea Spit. Though ideal in its elevation and position, it stood atop a steep, shifting sand dune. There were no roads, no jetty, or a straightforward approach. Just soft sand, dense scrub, and punishing winds that continually reshaped the terrain.

The lighthouse site stood atop a steep, shifting dune more than a kilometre from the beach. There was no jetty, roads, or friendly terrain.

A line was run ashore from the Resolute and anchored on the beach. Three specially built surf punts, each capable of carrying up to two tonnes of cargo, were hauled along the line to the beach. Above the high water mark, workers constructed a large storage shed.

Then came one of the most ingenious solutions of the project: a wooden, horse-drawn tramway stretching from the beach to the top of the dune. Made from locally milled hardwood, the timber rails were greased with animal fat to reduce friction and laid directly on the sand. Iron rails would have been too heavy and costly to ship. A flatbed wagon — drawn by horses via a whim or, at times, pulled by men — trundled up and down the incline, ferrying bricks, timber, iron tanks, barrels of water, and casks of lime.

It was slow, gruelling work. The incline was steep, and the rails constantly shifted or vanished under windblown sand. When storms hit, the entire system needed to be reset. Still, load by load, the tower crept upward.

The Rooneys faced the immense challenge of building a solid foundation in what was essentially drift sand. A concrete block measuring 4.6 metres in diameter was poured into a hole excavated in the dune, accompanied by a ring of three rows of 1.5-metre cast-iron plates bolted together and lowered into place. Shingle collected from the nearby Picnic Islands was rinsed with salt, and cement casks from Sydney were used to create concrete. All 508 tonnes of concrete were hand-mixed in buckets and poured layer by layer.

The salt-laden environment meant that corrosion was a constant battle. The lighthouse was lined with brick to offer insulation and strength.

Ten tiers of cast-iron plates were bolted one on top of the other above the base. The lantern room, crowned by a copper dome and weathervane, topped the tower. A winding staircase led to the gallery, 30 metres above ground and 130 metres above sea level, offering a spectacular view.

Work began in earnest in 1869, and the light was first exhibited in May 1870. Around the tower, supporting buildings were constructed, such as the head keeper’s cottage, assistant quarters, an oil store, water tanks, and supply sheds. All were designed for endurance in the face of isolation.

The light itself

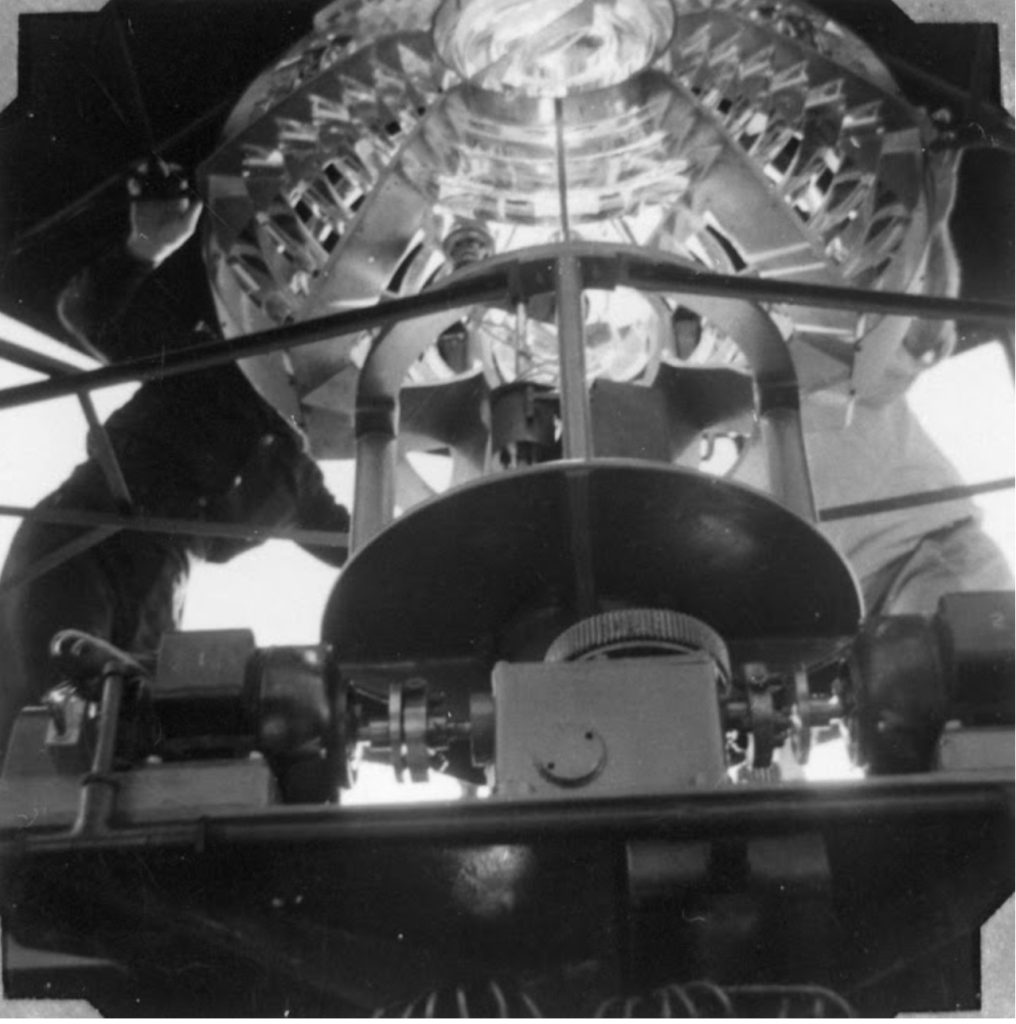

The original light source was an Argand oil lamp with concentric wicks, initially fuelled by colza or rapeseed oil and later by kerosene. Early records indicate that a First Order dioptric light was installed, which flashed every two minutes and had a range of 20 nautical miles, sweeping the hazardous Breaksea Spit.

The light’s power increased in 1917. By 1923, it underwent another upgrade, and the light source was converted to an incandescent mantle using vaporised kerosene from a Kitson burner. The light rotated via a clockwork mechanism that had to be wound up by the keepers at regular intervals.

Sandy Cape and Bustard Head lighthouses were eventually converted to electric operation in the 1930s. Around this time, the original lens was likely replaced by a Fourth Order lens.

The incandescent kerosene mantle system was eventually replaced by a 1,000-watt quartz halogen bulb powered by a 120-volt system. Its 500,000-candlepower beam was visible up to 28 nautical miles away, and its loom extended even farther on clear nights. The light revolved at three rotations per minute, flashing twice every ten seconds.

Control of the light station was transferred to the Commonwealth in 1915. The site was returned to the Queensland Government in 1997 and is currently managed by Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service.

The lighthouse keepers

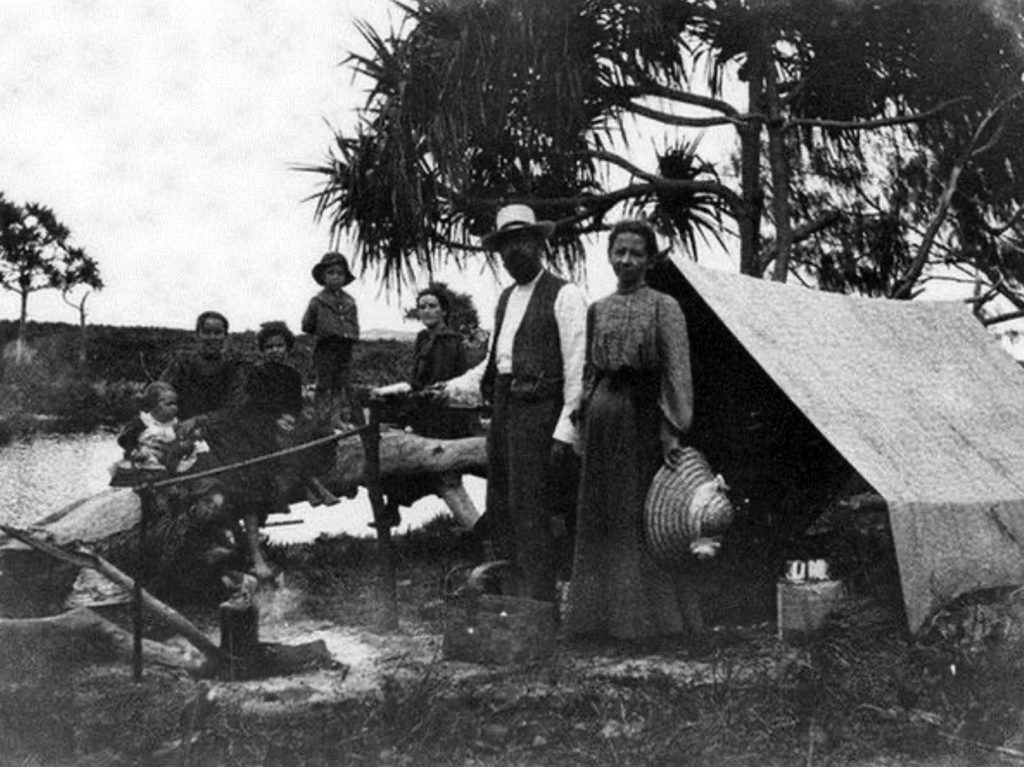

The men — and sometimes women — who kept the light faced loneliness, hardship, and the unforgiving demands of duty. Their lives were defined by routine, ingenuity, and fierce self-reliance. Living at Sandy Cape was not for the faint-hearted. Keepers and their families endured long months without contact from the outside world.

The original cottages were constructed from weatherboard and topped with iron roofs, accommodating the head keeper, three assistants, and their families. By the mid-1930s, these were replaced with timber-framed, fibro-clad residences.

The first head keeper at Sandy Cape was John Simpson. It was supposed to be 32-year-old James Maxwell, the assistant lighthouse keeper at Cape Moreton. Unfortunately, he drowned while fishing off rocks on Moreton Island in April 1870, before taking up his new position.

Simpson had previously served on Woody Island from 1867 to 1870. With his wife, Jane, he raised eleven children — five born in Brisbane and the rest at lighthouse stations. The Simpsons created a welcoming home, featuring a verandah draped in creepers, furniture, books, a piano, and a small garden where pineapples and cabbages battled the poor soil.

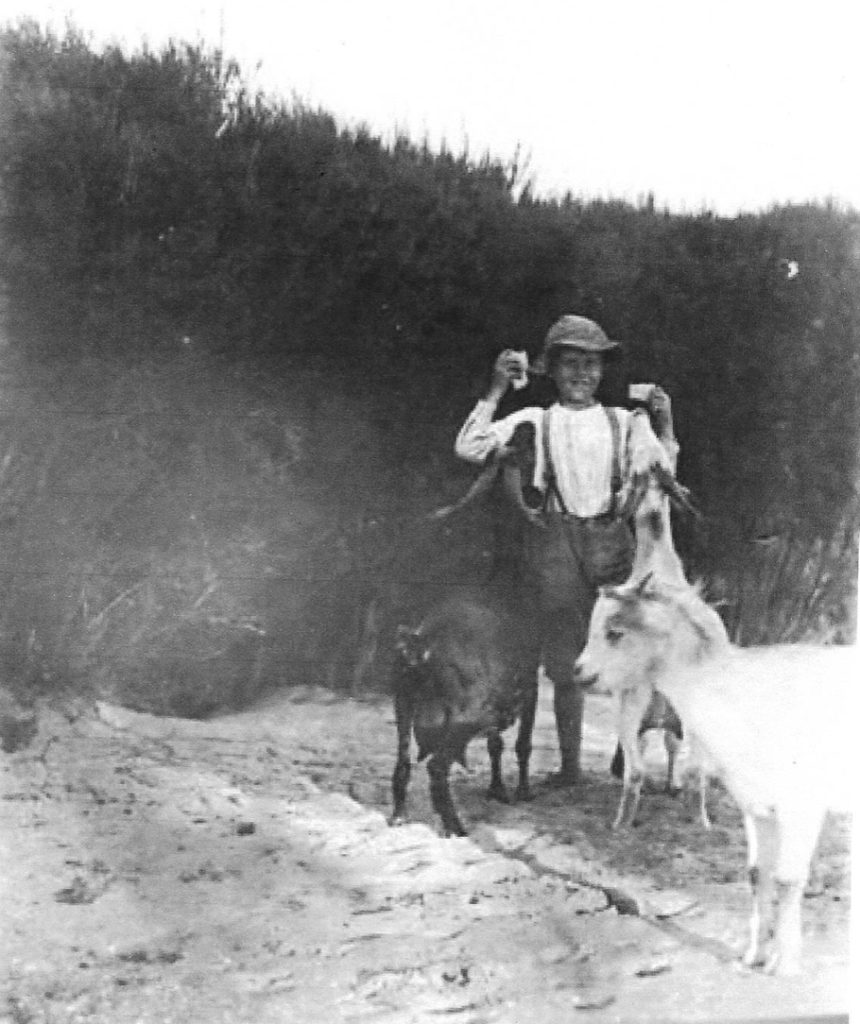

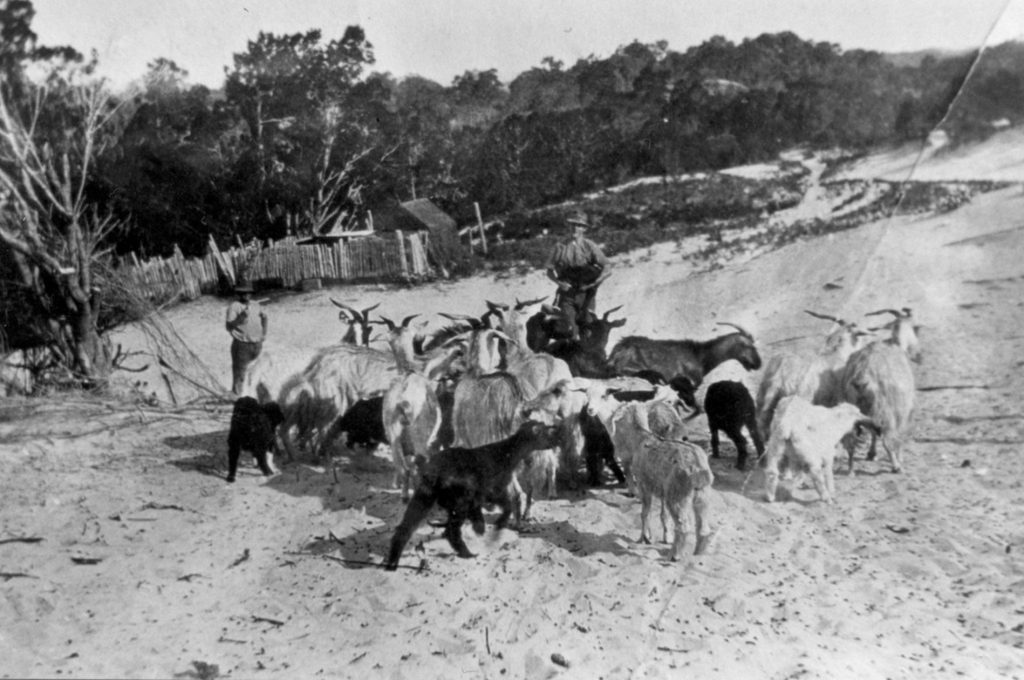

The goat herd consistently provided a steady milk supply, while the chickens supplied eggs. Manure nourished the vegetable garden. Protein sources included goats, fish, or the occasional cask of salted beef. Supplies such as flour, tea, and salt arrived by boat monthly, weather permitting.

Tragically, their daughter Edith Maud died in infancy in 1877, and in July 1882, John Simpson accidentally shot himself while hunting wallabies. A section of the transcript of the official statement of his death states:

…In running to secure the wallaby Mr Simpson stumbled over a log in the way;…the gun went off and was broken by the fall and…the charge lodged in his breast.

Both were buried in a picket-fenced cemetery south of the lighthouse.

Duncan Henderson arrived on the island as the head lightkeeper at Sandy Cape in 1887 and remained in the position until July 1900.

Another long-serving keeper, George Byrne, arrived in 1903 with his wife, Elizabeth (Bessie). They remained for a decade. Byrne had previously lost his first wife, Fanny, at Double Island Point in 1898. Between his two marriages, he fathered eleven children.

Local Aboriginal men were often employed in the late 19th century to assist with transporting supplies when boats arrived. Their contribution was essential, yet little was formally recorded.

A school and its headmistress were also provided. During World War II, the lighthouse site was the RAAF No. 25 Radar Station. Thirty men were based in huts in a nearby valley. The bunkers remain a popular attraction today. During this period, the keepers and their families resided at the lighthouse.

I will provide more details about the school and the operation of the radar station in future blogs.

The light goes silent

Sandy Cape was automated in April 1991 and fully de-staffed by June 1994. This automation marked the end of more than 120 years of human presence, during which the light was tended by hand. While the transition to automated, powered systems was inevitable, many saw it as a sad conclusion to an era when lighthouse keeping was a way of life. For the first time since 1870, the site lacked the steady human presence that had once breathed life into its windswept dunes.

Sandy Cape’s light is now solar-powered and monitored remotely, a significant change from the daily grind of trimming wicks, winding clockwork mechanisms, and hauling kerosene drums uphill.

Tales of heroism and tragedy

Sandy Cape has witnessed daring rescues and profound personal losses throughout its history, even after the establishment of the lighthouse. This underscores the perilous nature of maritime activities at Sandy Cape and the lighthouse’s crucial role in aiding shipwreck survivors.

Despite the beacon’s reach, nature could not always be tamed. The lighthouse keepers often served as rescuers, aiding shipwreck survivors who staggered ashore, battered yet alive.

On 28 March 1879, the Ottawa ran aground just south of Indian Head. While the crew went ashore to seek assistance, local Aboriginal people reportedly raided the ship’s cargo, particularly its supply of spirits.

In October 1884, the steamship Chang Chow, which was on its way from Sydney to Hong Kong with predominantly Chinese passengers, ran aground on the Sandy Cape shoal while attempting to navigate the passage between Breaksea Spit and the dangerous rocks of the shoal. Though she managed to free herself due to the rising tide, she suffered considerable damage to her hull and was able to berth southeast of the lighthouse and north of Indian Head. The 119 passengers and 70 crew members were sent ashore in the dark and during a frightful easterly storm. Some of the boats capsized, and several passengers drowned. After reaching the lighthouse, they were directed to seek help from the Woody Island lighthouse by walking down the western coast.

In late October 1895, the captain and crew of the brigantine Sarah Pile managed to safely reach the lighthouse in the ship’s boat after it was stranded on Breaksea Spit. The stricken and waterlogged Sarah Pile was towed to Horseshoe Bend in the Mary River by the steamer Llewellyn, and the captain and crew taken to Maryborough.

In 1904, the Aramac struck Breaksea Spit multiple times but managed to continue sailing. However, after 24 kilometres, the vessel began to leak significantly. The crew and passengers evacuated to boats and safely reached Burnett Heads and Baffle Point. The captain and six crew members remained aboard and successfully anchored the Aramac in the sheltered waters of Platypus Bay.

In January 1905, the schooner Waiwerra, engaged in collecting beche-de-mer, was wrecked approximately one mile south of Sandy Cape. Three Aboriginal crew members reached the lighthouse and reported that the vessel had struck at daylight. Captain Thompson, his son, the mate, and eight Aboriginal crew members departed in a whaleboat without sails or provisions, heading into the wind. Two dinghies, each carrying three Aboriginal men, also left the wreck. One dinghy capsized shortly after departure, nearly drowning its occupants before they reached safety. The fate of the other dinghy’s crew was initially uncertain, but later reports confirmed their arrival at the lighthouse. The government dispatched the steamer Albatross and another vessel from Rockhampton to search for survivors.

On 27 September 1914, the SS Marloo, a 2,628-ton steel steamer formerly known as the Francesco Crispi, collided with Sandy Cape Shoal in calm waters. The vessel was beached on Fraser Island, where all crew members and passengers were safely rescued. This incident was later attributed to the captain’s negligence.

For the families stationed at Sandy Cape, every wreck or distress signal served as a stark reminder of their solemn duty. In those moments, their isolation took on a deeper meaning, reminding them theirs was not just a lonely existence but a vital watch over one of Australia’s most dangerous coastlines. Their presence could mean the difference between life and death.

However, there were also tragedies close to home, as accidents, illnesses, and the relentless hardships of isolation took their toll. Tragedy struck the Walker family in June 1875, when the infant daughter of assistant lighthouse keeper Francis Walker and his wife Mary was born at the lighthouse but died four days later. Three years later, a death adder bit and killed their 10-year-old daughter, despite desperate first aid efforts from her family and other residents. It was reported at the time that no less than four death adders had been killed close to the buildings in the three months before the tragedy. Simpson believed the little rain over the previous two years had resulted in swamps drying up, and they were driven to the houses in search of water.

While relieving John Kidd as lighthouse keeper in March 1919, 66-year-old Harold Gasson died of heart failure.

Dealing with a sudden sickness in a remote location that required hospitalisation was sometimes an ordeal, as experienced with the wife of acting head lightkeeper Mr Jackson in September 1936. Mrs. Jackson, suffering from pleurisy and influenza, was transported from Sandy Cape to Maryborough General Hospital. The journey began with a motor launch navigating rough seas to Scarness, followed by an ambulance ride to the hospital, totalling ten and a half hours. Complications arose when the launch, Juanita, was delayed due to its skipper being away, necessitating coordination among hospital staff and customs officials to ensure Mrs. Jackson received timely medical attention.

A dark chapter at Sandy Cape

While the history of Sandy Cape Lighthouse is largely one of endurance and service, it has also experienced moments of darkness.

One such story occurred in 1900, when assistant lightkeeper John Halford, a 59-year-old married man, was charged with the unlawful carnal knowledge of a seven-year-old named Eva Melican at Sandy Cape, the daughter of fellow assistant lightkeeper Stephen Melican and his wife Mary.

The alleged incident occurred in September of that year. Evidence presented in court described Halford’s subsequent attempted suicide while in custody. He was found with a severe throat wound in a water closet but survived.

The case highlighted the vulnerabilities inherent in isolated postings and remains a sobering footnote in the lighthouse’s long and otherwise proud history.

K’gari, the largest sand island in the world!

Fraser island

Excellent read. Australia has a rich history of lighthouses, and I am sure they are all unique. However, your article has allowed me to gain a better understanding of the design and elements.

Your Gaussian blogging, Robert, is always at the gold standard.

Robert. Another great story on Fraser Island….’an island of silvery sands’. Also known as ‘the big timberland’. Keep up the excellent work.

Well done Robert.

As a self-confessed pharophile, I can see the hours of research you have undertaken on this lighthouse – with interesting results. There are many similarities between Sandy Cape and the nearby Bustard Head towers.

Actually, Bustard Head just predates Sandy Cape due to ‘some admin error’; it was scheduled to be No 2 of this pair, but Sandy Cape needed to be higher so the light would reach further out across Breaksea Spit. The design of each tower with exterior stairs reaching the entrance door well above the ocean relates to wave-swept towers overseas.

As the stairs at Bustard Head continually leaked, the exterior stairs were repositioned inside the tower, and the fuel initially stored in this room was stored in a separate fuel shed. There is a photo of the Bustard Head tower pre-erected in the Hennet and Spinks yard in England. The cast iron panels are approximately 20mm thick and weigh about one ton each. Each panel is identified separately: ground level is ‘A’ – ‘1’, ‘2’ ‘, 3’, etc. Next level up is ‘B’ – ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’, etc, then ‘C’.

Love to hear if the Sandy Cape tower has similar identifying marks on the panels.

Interesting story relates to the Breaksea Spit Lightship 1918-2000 – in your spare time, Robert.

Cheers, Ron Turner

Hi Ron.

I can’t compete with your lighthouse knowledge, so I really appreciate your input. I did touch on the Breaksea Spit Lightship in my blog about the Maheno and nearby shipwrecks, but I agree it deserves its own dedicated story. It’s such a fascinating and unique part of our maritime history.

If you’d like, I’d be delighted to feature a guest blog from you on the topic.

Another great read about the courage and tenacity of the first European settlers of Australia.

Thanks for your interesting article. Graeme (?)Hiley and I visited the lighthouse 50 years ago. On the way up on the northwest beach, we saw the remains of a ship, wrecked in the late 1800s. (Can’t remember the name.)

Wal Smith identified the piece of timber that I salvaged as derived from the U.S.

Thanks, Peter

I wonder if you saw the wreck of the Panama.