While Operation Jaywick in its simplicity was a resounding success; Operation Rimau in its sophistication was an abysmal failure.

Brian Smith

Introduction

In just a few months, the Japanese managed to dismantle an empire in South East Asia the Europeans took centuries to build. The attack on Pearl Harbour in early December 1941 was preceded by the Japanese invasion of the Malay Peninsula, an hour before. That operation was the first step in a drive to take Indonesia’s oil fields after the United States imposed an oil embargo on Japan.

After the surprise victory over the United States at Pearl Harbour, the Japanese were unstoppable for about a year. After Pearl Harbour and the Malay Peninsular, they took Guam and the Wake Islands and invaded the Philippines, Burma, the Dutch East Indies, and after a few months captured Manila, Rangoon, Singapore and Jakarta. By early 1942 the Japanese conquered or appeased Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, The Celebes, Timor, The Bismarks, The Gilberts, most of the Solomon Islands, and half of New Guinea. Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines were the only places that American forces held on for several months.

However, the Japanese defeat in the Battle of Midway in June 1942 was the beginning of the end for them. Two-thirds of their carrier strike force lay on the floor of the ocean and the same proportion of trained flight crew were wiped out. And they knew they couldn’t match the Americans in producing new replacement war machines.

While the Americans only had three aircraft carriers still in action in autumn 1942 after Pearl Harbour and other skirmishes, a year later they had 50. Their war production line was remarkable. Thousands of aircraft were being produced and this was a decisive factor in defeating the Japanese.

Despite this disadvantage, the Japanese were determined to hold onto their occupied territories in South East Asia. In doing so, they became more desperate and barbaric, particularly in their treatment of prisoners of war. Thousands of British and Australians were transported from Singapore to work as slave labourers on the Death Railway between Burma and Thailand.

The Japanese were angry at the destructive operation against their fleet by Operation Jaywick in late September 1943. They couldn’t believe that a force could penetrate their lines of defence and have the audacity to attack their fleet. They, therefore, concluded that it must have been organised by Singaporean and Chinese guerrillas from Changi Prison. On 10 October, the Japanese Military Police commenced a wave of reprisals, such as torture and executions against the local community, called the “Double Tenth Massacre”. The massacre saw 57 civilians arrested and tortured on suspicion of their involvement in Operation Jaywick. Fifteen of them died in Singapore’s Changi Prison.

Planning another strike against the Japanese

After successfully leading Operation Jaywick, Ivan Lyon, headed for England, the first time he visited his homeland in seven years. Basking in the glow of carrying out a daring operation behind enemy lines, he presented an even bolder plan to Combined Operations, Britain’s joint army-navy-air command, and her clandestine warfare agency, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Also, after visiting his parents, he found out his wife and son were not in Singapore but held in Fukushima internment camp 300 km north of Tokyo.

In Australia, the top brass of the Services Reconnaissance Department wanted an encore to Jaywick. Lyon had just been promoted from major to lieutenant colonel and was about to be recommended for the Victoria Cross. He had the image of a buccaneer in the mould of Sir Walter Raleigh or Sir Philip Sidney, an adventurer with a record of solid success. This was at an exciting time in England with the build-up to Operation Overlord, the allied invasion of France. “The hour of our greatest effort is approaching”, intoned Winston Churchill.

But what rankled the British most at this time was the loss of Empire – being kicked out of Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong and Burma by the Japanese in just three months was an ignominious blow to their prestige. There was even the possibility of losing India. There was a determination to retake the colonies and rebuild the Empire.

Lyon was from a respected military family who shared an ancestor with the Queen, the former Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, and he was determined to play his part in restoring British pride in South East Asia. Lord Louis ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten, the king’s cousin, was appointed Supreme Allied Commander in South East Asia by Churchill just a month prior to Jaywick.

(Left) British naval officer, Albert Victor Nicholas Mountbatten, the 1st Earl of Burma and the last Viceroy of British India.

The Services Reconnaissance Department was a cover name for Special Operations Australia (SOA). Mountbatten urged Lyon to seek American assistance for further raids against the former British island fortress of Singapore, as well as an attack on Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City). The first operation that was promoted by Mountbatten was Operation Hornbill centred on the Natuna Islands between Borneo and the South East Asian mainland. The plan was for Allied forces, including native Malays, to secretly occupy the small archipelago about 1,000 kilometres behind enemy lines, carry out raids on Japanese naval assets in French Indochina (now Vietnam), and on the shipyards of Malaya and Singapore. Essentially, this was the practical response to British imperial ambitions and restore their standing in Asia.

However, because of the complex political machinations between a mixture of incompetent, selfish and inept American, British and Australian commanders trying to work together to defeat the Japanese, Operation Hornbill never got past the planning stage. It was definitely killed off when the Americans refused to provide the submarine for the reconnaissance of the Natuna Islands.

Not deterred, Lyon instead outlined his desire for another strike in the very heart of the former colonial bastion of Singapore. The Japanese Imperial Navy moved its main base to Singapore and so an attack on shipping in that area was most desirable. He planned to smash sixty ships at anchor in the harbour and leave it a smoking ruin. It was a much more straightforward task as it didn’t need a massive base behind enemy lines.

Operation Rimau

The new single strike mission needed a new name. Rimau is the Malay word for tiger and no doubt was inspired by the tiger’s head on Lyon’s chest. While it was a downscale from Hornbill, it was a mission on a larger scale to Jaywick.

Operation Rimau planned to use 15 Sleeping Beauties. The Sleeping Beauty was a one-man submersible steel canoe set up for underwater travel controlled by a hydroplane and rudder. It was 3.9 metres long, with a 68.6 cm beam and was made of mild steel and aluminium.

(Left) A Sleeping Beauty in action.

They weighed 270 kilograms. Driven by a silent electric motor powered by four car batteries, they could travel 50 km to a target at a top speed of four and a half knots, then be submerged for a limpet mine attack on enemy shipping, at a speed of three and a half knots. They could also carry nine limpet mines which were sufficient to sink two 10,000-ton ships if correctly placed.

While in England, Lyon saw firsthand the operation of the Sleeping Beauties and was very impressed. The pilot, clad in a rubber diving suit equipped with breathing apparatus, stretched out in the cockpit with his nose almost level with the rim controlling the canoe by a joystick. After flooding two ballast tanks and diving, he could travel under water and navigate with the use of an underwater compass or have his head protruding above the surface for better visibility. They were considered more superior to the more fragile rubber and wooden folboats used in Jaywick. Trials in Britain, in the presence of Lyon, showed how easy it was to approach naval ships unseen and attach dummy mines to their hulls in almost complete silence. Lyon asked for 15 to be shipped back to Australia as quickly as possible for members of the Jaywick team to start practising.

Meanwhile, it was realised that the Sleeping Beauties were too large to be carried in junks close to Singapore Harbour and would have to be moved in special containers attached to the hull of a submarine. For that task, the Royal Navy nominated the largest submarine in the British fleet, HMS Porpoise commanded by Lieutenant Commander Hubert Marsham. Porpoise was already fitted with a mine-laying casing which ran the length of the hull, and it was hoped to adapt this to carry each Sleeping Beauty in a special, watertight container. Time was of the essence as the raid on Singapore had to be carried out before the monsoon started in November and the numbers to carry out the mission had to be more than double Jaywick’s.

Back in Australia in time for Christmas 1943, Lyon assigned Donaldson as second in command and recruited the brilliant young Captain Page, both from Operation Jaywick. Lyon asked the operatives from Jaywick to take part in Operation Rimau. However, only “Poppa” Falls, “Happy” Huston and “Boof” Marsh agreed.

Sixty recruits were selected to start in a camp at Potshot, near Exmouth in Western Australia in July 1944. Further south, another training area was established in Careening Bay on Garden Island, just off the coast of Fremantle for the instruction and practice on the Sleeping Beauties. The training group was culled to 32, known as Group X, for the final training block.

Meanwhile HMS Porpoise arrived in Australia from Ceylon on 15 August. However, the “J” containers to house the Sleeping Beauties had not arrived. Lyon immediately called a conference to discuss the best method of loading stores and the Sleeping Beauties. Rimau had to be launched by September.

The final selection of the operational team was made by Lyon and Davidson. There were 15 men from Group X – Major Reginald Ingleton, Lieutenants Bruno Reymond, Robert Ross, and newly-married Victorian Albert “Blondie” Sargent; Warrant Officers Alfred Warren and Melbournian butcher Jeffrey Willersdorf; Sergeants Colin Cameron from Victoria and David Gooley; Corporals Archibald “Pat” Campbell from Queensland, signals experts from Perth Colin Craft, Roland Fletcher, and Western Australian Clair Stewart; Lance Corporals John Hardy and Queenslander Hugo Pace; and mechanic Private Douglas Warne. Sub-Lieutenant Gregor Riggs was the Sleeping Beauty expert. Englishman Major Walter Chapman from the Royal Engineers and Lieutenant Walter Carey made up the submarine crew with Commander Marsham. The remainder were those from Operation Jaywick – Lyon, Davidson, Page Falls, Huston and Marsh.

HMS Porpoise. It was the last and 75th Royal Navy conventional submarine lost during WWII.

The role of the submarine was crucial. It was to set down the party at Merapas Island and pick the men up again during the night of 7 and 8 November. Chapman and Carey would supervise the unloading of the men, return to Australia with the submarine and then go back into the operational area to organise their extraction. This was to ensure the men were safely recovered.

HMS Porpoise finally left the Garden Island Naval Base on 11 September with the Rimau party. The Sleeping Beauties had finally been loaded into the submarine through the forward hatch and accommodated in empty torpedo compartments , something that Marsham maintained was impossible. The “J” containers were used to carry stores on the submarine’s hull.

The targets for attack specified in orders from Lyon were Singapore’s man-of-war and explosive anchorages, shipping at Keppel Harbour and the Empire Dock, and the wharves at Bukum and Samba islands. It was a high stakes, high risk strategy but seen as important for the Allied cause in the Pacific. To overcome the Sleeping Beauties’ 50 kilometre range limit, the Rimau party would capture a junk off the coast of Borneo and, after loading the Sleeping Beauties on board, anchor it and have an officer carry out a reconnaissance from Subar Island, which had previously served as Jaywick’s forward observation post. They planned to secretly moor the junk near Labor Island to launch the Sleeping Beauties. After attaching the limpet mines, they would scuttle the Sleeping Beauties and the junk in deep water and escape to their base on Merapas Island in folboats, and await their pickup.

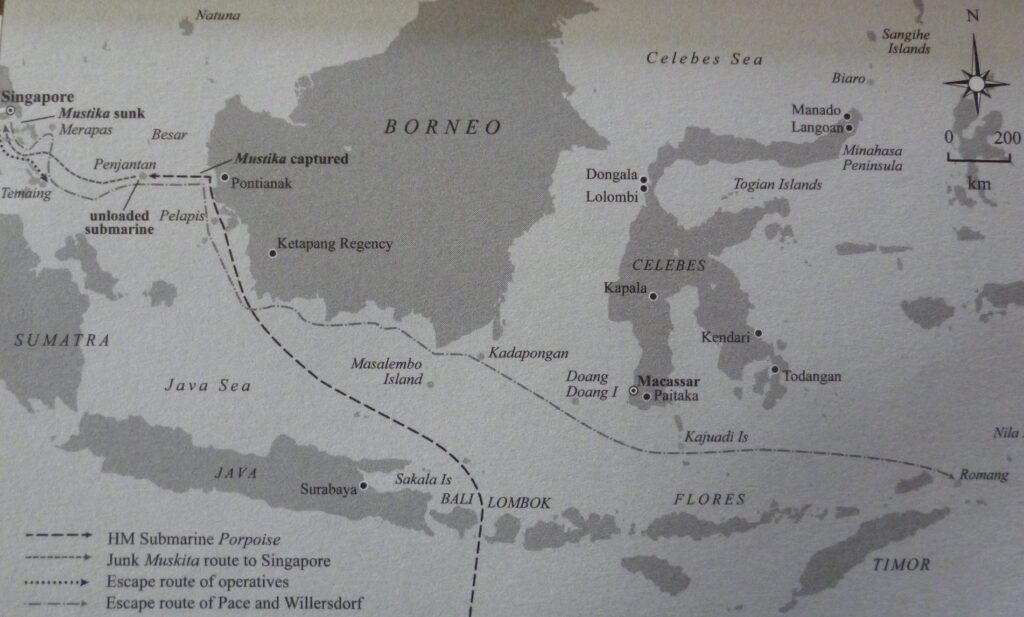

The map showing the route taken by the Rimau crew. It also shows Pedjantan Island where the submarine was unloaded.

In addition to small arms issued to each man, they carried Bren guns, nine millimetre Sten guns fitted with silencers, hand grenades and an anti-tank gun, but they knew the success of the campaign relied on stealth and remaining undetected and not having to use any of the weapons. The submarine reached its appointed destination off Merapas Island without incident on 23 September. Davidson and Stewart paddled ashore at dusk and spent the next 24 hours investigating the island. They were picked up the next night and confirmed the island was suitable as a rear base.

The troubles begin

The first issue confronting Lyon was the realisation that the Commander of the submarine, Lieutenant Commander Marsham was on the edge of a nervous breakdown and should never have been allowed to take charge of the drop-off operation. This weighed heavily on Lyon when he made the decision to not to leave the stores on Merapas Island unguarded and ordered Carey to stay on the island to protect the stores, a departure from the original plan. Lyon knew Marsham would be unable to make it back from Fremantle to pick up the Rimau commandos, and every man’s life would depend on solely Chapman as the only officer who would return for the recovery.

The moustachioed Chapman epitomised the superior English officer the Australians despised. They called him the “Pommy Pongo Plumber”, but now he was going to be their life line.

After unloading the gear, the rest of the party re-embarked Porpoise and went in search of a junk to take the Rimau party to the target area. After a few days, on 28 September, they found an Indonesian junk off the west coast of Borneo called Mustika and took control and the crew were boarded on the submarine and taken to Fremantle. The Sleeping Beauties and explosives were safely unloaded onto Mustika offshore of Pedjantan Island. On 30 September, HMS Porpoise left for Fremantle and the heavily-laden junk for Singapore Harbour.

The Malayan junk Mustika, captured for use in Operation Rimau. NAA A3269, Q11/58(B).

Realising Carey could keep an eye on the stores 24 hours a day, Lyon dropped off Warren, Cameron and Craft on Merapas Island and left for Singapore Harbour. One of the changes by the Japanese since Jaywick, however, was the increase in sea patrols by converting junks and small boats around the islands run by Malay volunteers who earned cash rewards for any successful outcomes. Flags on passing ships were scrutinised and unbecknownsted to Lyon, vessels approved for business carried a red anchor on a white background, along with the Japanese “poached egg”. Mustika flew no flags and was immediately under suspicion.

Only one hour before the Rimau raid was due to begin on the afternoon of 10 October, they were in the Phillip Channel which was busy with many Japanese warships preparing for the Battle of the Philippines. They were forced to sail close to shore and were spotted by a Malay patrol boat which sped up to intercept them. Lyon had a plan to entice the approaching crew on board by speaking Malay to deal with the situation.

But things went horribly long when one of the Rimaus fired at the approaching boat, and suddenly a hail of bullets were fired killing three of the Malays. Two others escaped overboard swimming back to shore, with a story to tell. Suddenly, in an instant, the whole operation was virtually over before it had started.

However, Lyon and Davidson, sons of Empire, were both driven by the need to strike back at the Japanese. Page also wanted his chance to strike back at the barbarous men who had taken his father into captivity. Between them, they quickly decided to take to the folboats and the rubber supply boat and scuttle the Mustika and Sleeping Beauties with the explosives.

Lyon, Davidson, Campbell, Warne and Stewart would paddle the rubber supply boat to Subar Island where Ross and Huston had already paddled in a folboat the night before to keep watch on activities in Singapore Harbour. Three folboats, under the command of Lyon, Davidson and Ross would proceed into the harbour and attach limpet mines to their targets and reassemble on Pangkil Island.

Page and the other 12 Rimaus would paddle to Merapas Island and reunite with the four caretakers left on the island.

The ensuing battles, the escape and the betrayal

While Japanese records aren’t conclusive, it appears Lyon was successful in blowing up three ships. A Japanese signal that was later intercepted mentioned three unexplained wrecks off Singapore on Admiralty charts. It could be said, at least Operation Rimau achieved something.

However, the next day, in Australia, code-breakers intercepted a Japanese naval message which alerted the SOA controllers in Melbourne that Operation Rimau was in deep trouble. The Japanese army was looking for “about twenty Causcasians in the Riau Archipelago who were engaged in a defensive stand”.

The retreating Rimaus couldn’t paddle directly to Merapas Island down the middle of the Riau Straits because it was teaming with Japanese naval vessels. Lyon left Davidson, Campbell, Huston and Warne on Pangkil Island while he, Ross and Stewart crossed the Riau Strait in darkness to Soreh Island, which he thought provided a much better vantage point. Davidson found out from a friendly Malay that Lyon’s presence on the island had been betrayed by another Malay which led to heavily armed Japanese troops racing to the island on a barge. The next night, Davidson ordered Huston and Warne to head for Tapai Island towing the rubber raft, while he and Campbell paddled to Soreh Island to warn Lyon. Late the following day, about 45 Malay volunteers under Japanese command landed on the island and a fire fight ensued.

Meanwhile, Page and the men with him were paddling for Merapas Island, still 100 kilometres away. Huston and Warne, after hearing the gunfire on Soreh Island, sank the rubber supply boat and left for Merapas Island. They all arrived safely and could do nothing except wait for the planned pick up by HMS Porpoise.

The pick up plan was pretty clear. The Rimau commandos would return to base on Merapas Island after the strike and would be rescued by Porpoise on the night of 7-8 November. If the submarine failed to make contact with them that night, it would continue returning to Merapas Island each night for 30 nights until 8 December.

(Right) This photo taken of Lieutenant Commander Hugh Mackenzie onboard HM Thrasher in 1942.

Meanwhile, on returning to Fremantle, Marsham asked to be relieved of duty. The responsibility of rendezvousing with the Rimau party was passed onto HMS Tantalus captained by Lieutenant Commander Hugh Mackenzie from the Royal Navy.

Mackenzie had a reputation as a successful and aggressive hunter with an unenviable record of sinking enemy ships. That was his DNA. He was disappointed with his recent missions in the South China Sea where there was a lack of enemy targets, simply because the Japanese had few ships by that time of the war and convoys were rare. He was also continually diverted to pick up downed pilots and assist with special service operations.

When Mackenzie was ordered to abandon his patrol duties yet again to pick up “a bunch of adventurers from some commando outfit”, he was furious. He wanted to hunt down Japanese targets. Despite being given absolute specific orders to rescue the Rimau commandos, he had other ideas for his mission. For the Rimau commandos, Mackenzie was not the right man to help them escape and return safely to Australia.

Four days later, on 16 October, with Chapman and Corporal Richard Croton as the link to Operation Rimau on board, the submarine left Fremantle armed with 17 torpedoes. As soon as the Tantalus entered the Java Sea on 20 October, on its way to Merapas Island, McKenzie spent his time on the periscope looking for Japanese ships to attack.

As the evening of 7 November approached, Tantalus was positioned to make the rendezvous. However, Mackenzie told Chapman that because the main object of his trip was to take offensive action against the enemy, he decided it was “improper to abandon their patrol in order to pick up the party”. He decided to continue patrolling for enemy ships and justified it on the basis his original orders gave him a month’s window for the pick up.

On 11 November, Mackenzie attacked an unarmed trader under the command of a single Japanese soldier, a few kilometres north-east of Merapas Island. The Tantalus finally arrived back at the rendezvous site on 21 November carrying 15 torpedoes, two weeks after the desperate Rimau commandos were expecting her.

That night, Chapman and Croton headed for the island. Chapman struggled across the slippery rocks and didn’t want to be there. His fitness wasn’t great after being cooped inside a submarine for all but four days in the previous two months. But he was the only one who knew where to look. At one point, Croton aimed his gun at Chapman ordering him to continue the search for the Rimau camp and the men.

After sleeping most of the night, they searched the island the next day. While they saw three Malays working on the coconut plantation in the distance, they did not approach them. They did find a couple of empty camp sites with evidence of recent habitation and evidence they were Rimau campers. There was no evidence of any fighting, and they returned to the submarine the next night. Instead of interrogating the Malays, or landing a larger boat party or circumnavigating the island, or returning on subsequent nights, as previously ordered, Mackenzie simply sailed away.

In the final instalment in two weeks, I will outline the fate of the men from the Jaywick and Rimau operations.

A good article but unable to find the follow up. Can you assist please?

The title is misleading as a Z special unit was the administrative unit for Special Operations Australia (SOA) also known known by its cover name during World War II as the Services Reconnaissance Department. Operation Rimau was an SOA operation, whereas operation Jaywalk was a joint SOE/RAN operation which was provided some assistance by SOA. The official records provide greater clarity, however, if you’re after a concise explanation please email me and I will forward you paper extracted from the magazine commando which I’m the editor.

Doug Knight, Australian Commando Association.