Introduction

This month 80 years ago, a small, unassuming ex-Japanese fishing vessel was pivotal in an audacious and successful secret commando operation by a handful of courageous Australians against the mighty Japanese war machine during World War II. Its history and how it got into Australian hands is remarkable. So is the bravery of its crew.

It all started just prior to the chaotic fall of Singapore, where civilians looked to flee on boats and ships. Australian master mariner Captain Bill Reynolds, who had been stationed in Malaysia during the Japanese invasion of Singapore, salvaged the Kofuku Maru to safely evacuate hundreds of civilians from outlying islands to Sumatra. It avoided enemy aircraft or attacks from nearby vessels, unlike other boats.

Operation Jaywick involved Australian and British Special Service men sneaking into the Japanese-held Singapore Harbour to sabotage as many ships as possible, using the Kofuku Maru under its new name – MV Krait. It is credited with sinking more enemy ships than any other Royal Australian Navy ship.

The operation was part of a series of covert operations by a secret Special Operations Unit called Z Special Unit between the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Royal Australian Navy.

Extraordinary and heroic deeds at the fall of Singapore

Captain William Roy “Bill” Reynolds, from Williamstown in Victoria, served on destroyers as an officer in the Royal Naval Reserve during World War I. Following the war, he worked as a merchant seaman, mining engineer and master mariner in the waters around Singapore and Malaya.

(Left) Bill Reynolds. AWM PO1806.006.

Six weeks before the surrender of the Singapore garrison by General Arthur Percival on 15 February 1942, 61-year-old Reynolds offered his services to the Navy and was given command of a Japanese fishing boat which had been seized in Singapore Harbour when the Pacific War began. The Kofuku Maru was built in Japan in 1934 and was owned by a Japanese fishing firm in Singapore. In peace time, it collected fish from fishermen at ports around the Anambas Islands to the north-east to sell at Singapore markets. As the Japanese advanced down the Malayan Peninsula, Reynolds was tasked with destroying any facilities in Singapore that may be of use to the enemy. He employed Chinese workers and refurbished the boat to make her more seaworthy.

As Singapore was falling, Reynolds took the old fishing boat to the “Thousand Islands” of the Rhio Archipelago where, in those terrible days, at least 50 escaped ships were sunk by Japanese bombers and more than 3,000 people were killed. He used the boat as a ferry to pick up and rescue refugees from the islands, small craft and even rafts and wreckage, and take them to Sumatra.

After dropping a boatload of refugees at the mouth of the Indragiri River from the island of Linga, Reynolds collided with a boat used by British Captain Ivan Lyon, who was also evacuating civilians from Singapore by boat 240 kilometres up the Indragiri River to the port of Rengat. The refugees would then cross the mountains to the west coast port of Padang and take their chances getting to India or Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). After watching Reynolds in the Japanese fishing boat take people out of Singapore Harbour without attention, Lyon believed it could take people back in. Both men discussed the idea when they briefly worked together rescuing civilians.

At the time of meeting Reynolds, Lyon was an Intelligence Officer at Army Headquarters in Singapore, and a liaison officer with the Dutch, before being sent to the Dutch-held Sumatra to help organise and supply an escape route – the “Tourist Route” – to safety in Ceylon and Australia for fleeing refugees.

Lyon came from an Army family and was a descendent of Thomas Lyon who left Scotland in the 17th century to settle in Warrington, Lancashire. His father was Brigadier-General Francis Lyon. After Royal Military College training, Lyon joined the Gordon Highlanders but was quickly bored with inactive service. He volunteered for overseas service with the regiment’s 2nd battalion based in Singapore. He arrived there at the end of 1936 and was recruited by the Defence Security Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Hayley Bell as an intelligence officer to track down Japanese spies. He found out, in the event of a war, the Japanese planned to launch, from their bases in Indochina, an invasion of Thailand and northern Malaya.

One of Lyon’s preparations for war was to spend a lot of his spare time and holidays sailing to familiarise himself with the seas and straits of the Singapore region. He learned about currents and rip-tides that flowed around the cluster of islands, meeting the headmen of Malay villages on the way and establishing contacts for the future.

He also sailed north to remote areas of Malay and Thailand and walked in the heavily timbered parts to check on likely routes the Japanese invaders would take if they invaded.

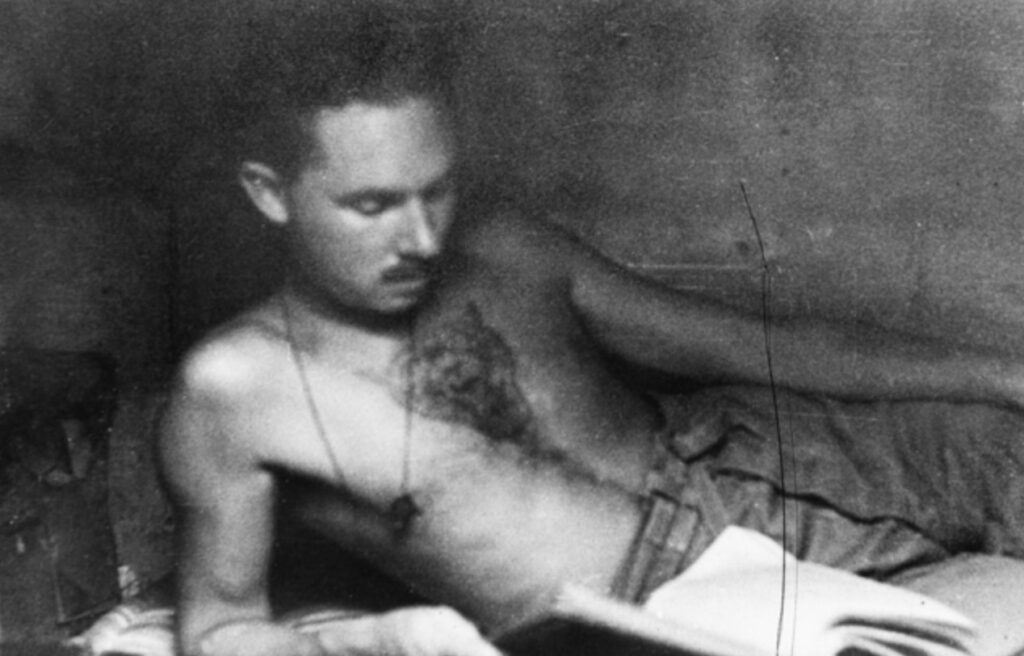

(Right) Lyon with his large tiger tattoo on his chest.

He was not your typical butch war hero. He possessed a spindly physique, had a habit of keeping silent and showed a nervous tenseness. But he had a personal ruthlessness about him. After a night of heavy drinking Tiger beer, he had a tiger’s head tattooed on his chest in brilliant scarlet, black and yellow. He called it Rimau, the Malay word for tiger.

In mid-1940, Vichy France controlled Indochina (Vietnam) and, later that year, was occupied by Japan. As the prospect of war with Japan loomed, Lyon began covert operations with free French sympathisers in Indochina. After Japan invaded Malaya and advanced towards Singapore, he established resistance groups within the local communities and set up secret supply dumps.

When the British ignominously surrendered “the Gibraltar of the Orient” one million Chinese, Malay and European civilians and 125,000 Allied troops, including 14,972 Australians mainly from the 8th Division, found themselves “guests” of the Emperor Hirohito.

When the Dutch East Indies surrendered a month after the fall of Singapore, Reynolds and Lyon separated. Reynolds escaped the Indragiri River in Sumatra up the Malacca Strait, between Malaya and Sumatra on the Kofuku Maru. He renamed it Suey Sin Fah and with a boatload of Chinese refugees, managed to steer his little fishing vessel through Japanese-controlled waters. A Zero floatplane did attempt to machine-gun them but missed. They sailed across the Indian Ocean to Ceylon and eventually to Bombay in India, During the journey, the boat’s engine was held together by copper wire.

Lyon commandeered a big proa, the Sederhana Johannes, at Padang, on Sumatra’s Indian Ocean. He escaped with 15 Europeans, a Chinese and a Malay on board. The Europeans included his own batman, Corporal Taffy Morris, his superior officer Captain H. A. “Jock” Campbell, Captain John Davis and Captain Richard Broome. The latter two helped organise the “Tourist Route” and who later landed secretly in Malaya to fight with the Chinese Communist guerillas.

(Left) Captain (later Major) Jock Campbell.

The Sederhana Johannes was old, sluggish and unseaworthy. She had no engine, and her sails were rotten. While Lyon was an expert small-boat sailor, having sailed in a small boat from Singapore to Saigon before the war, he knew little about the proas or how to sail them and was no master navigator.

Soon after leaving Sumatra, they were attacked by Japanese aircraft and again in the Indian Ocean. While the Europeans hid under bamboo matting, the Chinese and Malay waved hoping to deceive the Japanese pilots. Thirty-eight days after leaving Padang, and three miles short of Colombo, a freighter picked them up exhausted and covered in suppurating sores and boils. Lyon then went on to India.

After this experience, Lyon was still intrigued by the Kofuku Maru in British hands. He saw it as an invaluable aid to a plan to return to Singapore. Despite one of the worst defeats in modern warfare history, this young British officer was calmly planning, while on the run himself, how to return to Singapore and attack the Japanese.

While in India, Lyon used all his all the influence he had to win official backing for his plan and return to Singapore.

(Right) The Kofuku Maru later renamed the Krait. AWM 067338.

Many people he spoke to thought he was crazy. However, in New Delhi he managed to gain support of General Wavell.

When Lyon found out about Reynold’s escape and that the Kofuku Maru was in Bombay, he argued it was the boat to allow them to get behind enemy lines. He considered her to be the perfect camouflaged fishing craft, common before the war in South East Asian waters, and would be accepted by the Japanese as their own without suspicion.

Lyon believed that the operational base and starting point for the covert operation should be Australia, because the Singapore approaches from India and Ceylon would be more closely guarded than the wider and more distant route from Australia. Special Operations Australia originated in March 1942 when Colonel Egerton Mott arrived in Australia from Great Britain via Singapore and Java. He was a member of the Special Operations Executive, a body responsible for organising subversive operations in enemy territory and resistance movements in enemy-occupied countries. Lyon found himself discussing his plans with Mott in July 1942 who also provided support. Although this was at the same time all the Inter-Allied Services Department and its sections, including Z Special Unit, came under MacArthur’s command. He was an egotistical and conceited leader, who wanted only one conquering hero in the Pacific – himself. MacArthur cared little for the former British colonies in Asia. His main obsession in the Pacific War was the Philippines which he had promised to liberate after being driven out of that country by the Japanese in March 1942. Through his arrogance in ignoring the attack on Pearl Harbour which destroyed America’s naval power in the Pacific, his forces in the Philipinnes were unprepared for any follow-up attack by the Japanese, which, when it came, wiped out much of America’s air power in the Pacific.

Lyon’s obsession with Singapore had a bit to do with the fate of his French-wife Gabrielle and their small son. While they were safely evacuated from Singapore directly to Perth before the surrender, Lyon was posted to a staff job in New Delhi following his escape from Sumatra. He cabled his wife to join him there. However, after gaining approval and prior to leaving for Australia, Lyon sent another cable to stay in Perth. Meanwhile, she had already left for India when he arrived in Australia. He received news not long after that the ship SS Nankin had been captured by the German raider Thor and Gabrielle and her son, along with the other passengers, were sent to Singapore, handed over to the Japanese, and interned as prisoners.

Organising a daring plan

Lyon reached Australia with the full backing of the British and a large budget of £11,000 to carry out his planned mission. He was accompanied by his fellow Singaporean escapee, Campbell, of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers.

Lyon, however, faced many hurdles in Australia. He arrived after the Battle of the Coral Sea when the immediate threat to Port Moresby and to Australia from the Japanese was removed. The critical battles were about to be fought in Papua and the Australians were more focused on that area and had no interest in supporting a raid behind enemy lines in far off Singapore, which posed no strategic advantage going forward.

Lyon outlined his plan to the director of Naval Intelligence, Commander Long. Lyon also used his family connections to get the ear of the Governor-General Lord Gowie, who played an important behind the scenes military role during the war while in Australia. Lord Gowie was a friend of he first Naval Member, Admiral Sir Guy Royle, and he passed Lyon onto to Royle, who gave his support to Lyon’s daring plan. General Sir Thomas Blamey and the Army also supported the plan, which was initially code named “Jock Force”. Lyon was to operate under the Inter-Allied Services Department.

Campbell became Lyon’s administrative head and behind-the-scenes organiser. The next step was to select his raiding party and to get the Kofuku Maru to Australia. In Bombay, the boat had been taken over by the Royal Navy and was renamed Krait after a thin and innocuous looking but very poisonous and deadly Malayan snake.

Reynolds was still the commander of the Krait and with his intimate knowledge of the waters around Singapore Harbour, he was ordered to sail her to Australia. But after two failed attempts to get to Fremantle because the ancient four-cylinder Deutz diesel broke down, she was eventually shipped on the deck of a British freighter and unloaded at Sydney Harbour in November 1942.

Meanwhile, Lyon became a little apprehensive about his plans after finding out his wife and child were held as prisoners of war, presumably in held in Singapore. He wanted to recruit the right people. The suggestion of his second-in-command came to him via an intelligence officer who was summoned to the Victorian Governor’s office In July not long after Lyon found out about his wife’s capture. To his astonishment, the officer had suggested to Lyon a covert raid, after which he outlined the plan he had come to Australia to organise. When Lyon said he needed a someone who knew canoes, could train others and was experienced in jungle-warfare, the intelligence officer suggested Lieutenant Donald Davidson as his second in command.

Englishman Davidson came to Australia in 1927 to work as a jackaroo in the Dirranbandi area and then a ring-barking contract in the Charleville district. With outback Queensland too stark and dry for him, he returned to England after five years, joining the Bombay Barmah Trading Corporation and went to work in the teak forests of northern Siam (now Thailand) and later Burma.

He loved the densely vegetated mountains, learning to live off the land and exploring areas where no Europeans had previously been. He was a brilliant canoeist, once travelling almost the full length of the Chindwin River in the centre of Burma. At the outbreak of WWII, he wanted to join the army but was refused. He volunteered anyway and was given a commission in the Burma Frontier Force. But when the Burmese Government introduced a law that prevented a European holding a commission in Burma unless he had a job to return to, Davidson decided to join the Australian Imperial Force.

While waiting for a ship to take him back to Australia, he was offered, and accepted, a commission in the Royal Navy. His wife and young daughter were evacuated to Australia in December 1941 after Pearl Harbour. Davidson left Singapore before the surrender and went to the Dutch East Indies with the Singapore Naval Base staff. He escaped the Japanese in a small boat from Sandakan in Borneo, rejoined his wife in Melbourne March 1942 and given a post at the Navy Office. In July that year he became second in command to Lyon in operation “Jock Force”.

Training and finalisation of the crew

At the Naval Depot near Melbourne, Davidson began recruiting volunteers.

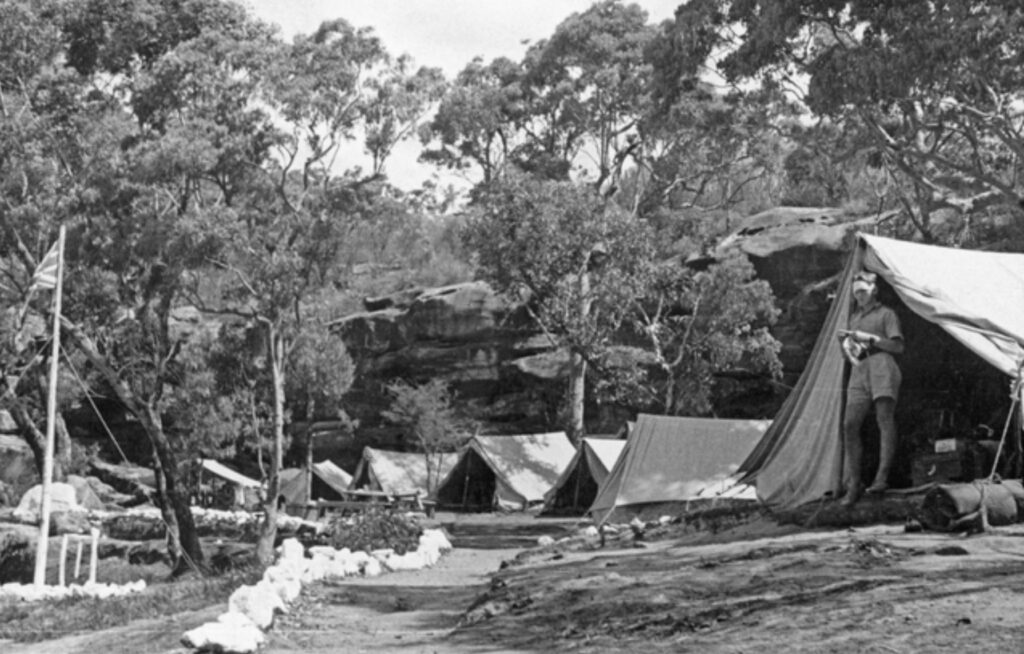

(Left) Tent lines at the Refuge Bay training camp. AWM PO1806.009.

They were called for “special service” and about 40 came forward. All except two, were about 18 years old, had only been in the Navy a few months, and never been to sea.

After interviews, Davidson and Lyon selected 17 men to do the training. They were told nothing about what exercise they were going to train for. Over six weeks at the Army Physical and Recreational Training School at Frankston, Davidson put them through tough physical sessions that included wrestling, boxing, running, climbing and engaging in unarmed combat.

Eleven men progressed to a secret training camp at Broken Bay, north of Sydney on the Hawkesbury River in September 1942. Called Camp Z, it was perched on the cliff-top in sandstone country overlooking the bay about four miles west of Palm Beach. The training took on a new urgency and focus. It was a tough, relentless slog. The men spent long hours each day on basic rations with practically no free-time, drinking or smoking allowed. The aim was for the men to “reach a state of perfect physical condition, capable of being maintained for six months”. One recruit later wrote,

“We trained about eighteen hours a day for three months. We trained in strict secrecy, with no smokes, no beer, no women, no nothing. It was hell – the kind of life you like only when you look back at it when you’re very old and want to impress your grandchildren”.

The men were soon very fit and learnt night movement, the use of weapons and explosives. Davidson trained the men in the swiftest and most efficient means of killing. They also learnt bush craft using a compass, reading maps and charts, how to move silently, camouflage themselves and their equipment, stalk an enemy, climb cliffs, and go without food and water for long periods. They spent hours each day mastering the canvas canoes – paddling silently, negotiating waves, rips and surf, righting an overturned canoe, limiting their silhouette at night, and approaching a ship or land without detection. On occasions, they had to paddle 320 kilometres over four days in both calm waters near the camp and in the rougher waters of the open sea.

An experimental two-man canoe built to fill in time at Refuge Bay. It was codenamed HMAS Lyon. AWM P01806.008.

The Krait left Refuge Bay on 18 January 1943 and took nearly two months to reach Cairns. With Reynolds as Captain, the crew was Davidson, Welsh coalminer Corporal “Taffy” Morris (medic), the three Leading Seaman canoeists, Scottish dairy farmer Walter “Pappa” Falls, Perth grocer’s assistant Arthur “Joe” Jones and Queensland banana farmer Andrew “Happy” Huston, and two reserve canoeists Mostyn “Moss” Berryman from Adelaide and apprentice cabinet-maker Frederick “Boof” Marsh.

It was a nightmare of a journey with the old worn-out engine breaking down off Newcastle and Coffs Harbour and the narrow beamed boat rolling and pitching. They were forced to stop in Brisbane for engine repairs. It was here, Irish Leading Stoker James “Paddy” McDowell joined the boat as engineer, as well as an experienced sailor, Leading Seaman Kevin “Cobber” Cain from Brisbane, a trained gunner and coxswain. After leaving Brisbane, the Krait broke down for the fourth time near Fraser Island. Unfortunately, Davidson’s malaria returned and he had to be left behind and ferried to the Maryborough hospital. The Krait limped up the coast and in the Whitsundays, had to be towed into Townsville where Davidson rejoined the crew. Finally, the Krait sailed into Cairns to be loaded with supplies and equipment, and its engine repaired.

At the last minute, one of Lyon’s most promising men, Captain Gort Chester was assigned to another mission in Borneo. His replacement was already in Cairns as part of Operation Scorpion who had trained with Z Special Unit at Wilsons Promontory. However, it faced problems behind the scenes and Operation Scorpion was called off. Once a young Lieutenant, Robert “Bob” Page from Sydney, reported to Lyon for duty, all the the men on Operation Jaywick came together at the “House on the Hill”, the Z Experimental Station above the town, which served as the operational centre for the Z Special Unit, an administrative unit for men who performed secret and unorthodox tasks.

Page was a second-year medical student at the University of Sydney. His father was Major Harold Page who fought in WWI as a member of the 26th Battalion and was awarded both a Distinguished Service Order at Gallipoli and a Military Cross for actions in 1918. Unbeknownst to Page at the time, his father was lost on 1 July 1942, along with 1,000 other Prisoners of War and civilians when the Japanese passenger vessel, Montevideo Maru, was sunk off the Philippines.

Sir Earle Page, who became Leader of the Country Party in Federal Parliament and briefly Prime Minister, was his uncle.

(Left) The House on the Hill – the Z Experimental Station in Cairns.

Meanwhile, Reynolds decided to leave the Krait after he was offered a job with the US Intelligence. He returned to Malaya to collect intelligence for the Americans. He planned to purchase a junk and make his way south through Japanese-occupied territories to Western Australia, posing as a man buying rubber and quinine.

It was decided to fit the Krait with a new six-cylinder Gardiner diesel engine – the only one in Australia. It was flown from Hobart and tested by McDowell and naval engineers.

Victorian Lieutenant Hubert “Ted” Carse, ex-Royal Navy and merchant marine with master mariner qualifications first heard about the Krait while in Townsville. Captain Lyon approached him, “we want you to navigate the Krait”. Carse replied “The Krait?…But she’s a tub with a worn out engine”. “She was a Japanese fishing boat”, Lyon responded, “that’s why she’s important”. Lyon asked Carse to go over the Krait carefully and report back what was needed. He said he couldn’t do that without knowing where it was going and how far? All he was told was it would take fuel for 13,000 miles. With her old engine and fuel capacity she had a range of only 800 miles.

Lyon wanted to recruit a cook before they left Cairns. They sought volunteers from the Army’s 7th Division stationed on the Atherton Tablelands, but the only two to offer their services were married with families which didn’t meet Lyon’s requirements. A young corporal, that was about to be boarded out of the Army because of ill-health approached Lyon offering his services as cook. While he admitted he wasn’t much of a cook, he did claim to be a “pretty good motor mechanic”. Queenslander Corporal Andy Crilly became the fourteenth man to join the Krait’s crew and quickly became known as “Pancake Andy” after his only cooking speciality.

Unfortunately, the new engine refit was continually delayed and with the persistent problems with the current engine, it was decided to abandon the planned departure to Exmouth.

The remaining naval personnel were transferred to Special Operations, and Lyon, who wanted to stay in Australia, was assigned to Special Operations, and became part of the Z Special Unit.

Operation Jaywick

Later in the year, Special Operations revived the Jaywick mission after the Krait was made seaworthy.

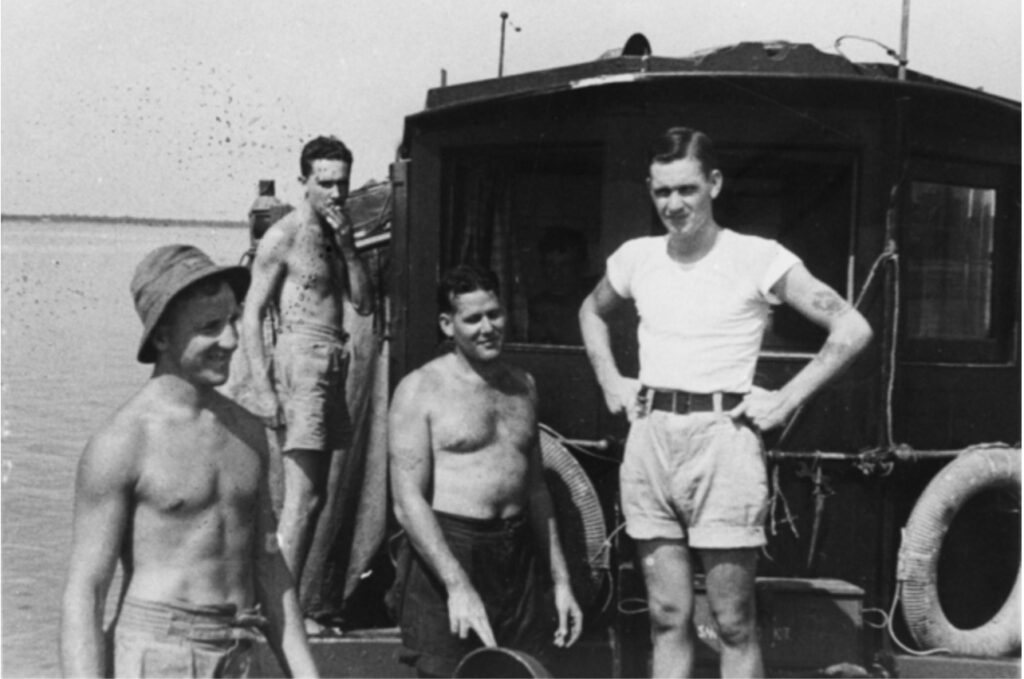

(Right) Four of the crew on MV Krait. L-R Huston, Lyon, Cain, Young. AWM 045413.

Just prior to the reassembly of the crew, Carse was sent to Melbourne for a final briefing with the Director of Naval Intelligence, Commander Long. He was given Dutch charts and provided with as much intelligence as he needed by the Dutch Admiral. He returned to Townsville at the end of July 1943.

Also, there was the addition of 22-year-old Western Australian telegraph messenger as the radio operator. Leading Telegraphist Horace “Horrie” Young was a bit of whiz with radios and after meeting Davidson in Newcastle, agreed to volunteer.

Lyon renamed the dangerous covert mission as Operation Jaywick, either after a seaside village on the Essex coast, or after the brand name of a popular lavatory deodoriser in Singapore, depending on what book or article you read. The mission’s aim was to attack Japanese ships in Singapore Harbour with magnetic limpet mines, in the same vein of the abandoned Operation Scorpion that was going to damage enemy ships in Rabaul. The personnel was small in number – six “operatives” to attach the mines using folboats or collapsible kayaks, and eight boat crew.

The fourteen Jaywick Commandos, ten Australian and four British, finally left Cairns for the 2,400 mile journey to the Exmouth Gulf in Western Australia on 8 August 1943. The Krait, fully loaded with men and equipment, sank ever deeper into the water as she left Cairns. This highly trained crew of special services personnel were a disparate group of men with various level of skills. Lyon, the commander and now a Major, was a professional soldier but with no deep-sea experience and no ability to navigate. Davidson was an expert canoeist and bushman, but he had never been to sea. Only four (Carse, McDowell, Cain and Jones) were real seaman, and of these, only Carse and McDowell, who both had long sea experience and training, could comfortably navigate the Krait on its long journey to Singapore, behind enemy lines.

The men had to live together in very cramped conditions for the long journey. The Krait was a small fishing vessel not designed for long journeys for such a large crew. It was little more than unstable platform only 80 feet long and just a standing-jump wide.

The Crew cramped onboard MV Krait on their way to Singapore with some showing the dyed skin. AWM 067336.

Number One hold near the bows held a huge amount of explosives including limpet mines and hand grenades. Food was in No. 2 hold, while No. 3 hold was the combined men’s quarters and radio equipment. No. 4 hold, directly under the wheelhouse, held enough diesel fuel to cruise 13,000 miles. On deck also were eight four-gallon drums of petrol to feed the small auxiliary engine which provided light and air pressure to start the 100 horse-power Gardner engine.

Also on board were cyanide tablets should the need for a quick death arise. In the event of capture, they would have the choice to take their own life rather than be tortured and reveal information about the operation.

The officers – Lyon, Davidson and Page – used No. 3 hold which was Young’s radio room. The others slept and ate in the covered curtained section above the engine room, except for McDowell, who sometimes slept in the engine room hatch or sometimes beside the engine if he was not satisfied with its performance. Carse slept on a bunk in the wheelhouse.

The mission – one of the most extraordinary Special Forces operations of all time

At Potshot, the US Naval Base at Exmouth, they loaded the vessel with military folboats, fuel and supplies. The folboats came from England and were found to be faulty, lacking some important parts and not as per the design specified by Davidson. They had to undergo many on-the-spot modifications to make each framework fit together and then fit correctly into the outer skins.

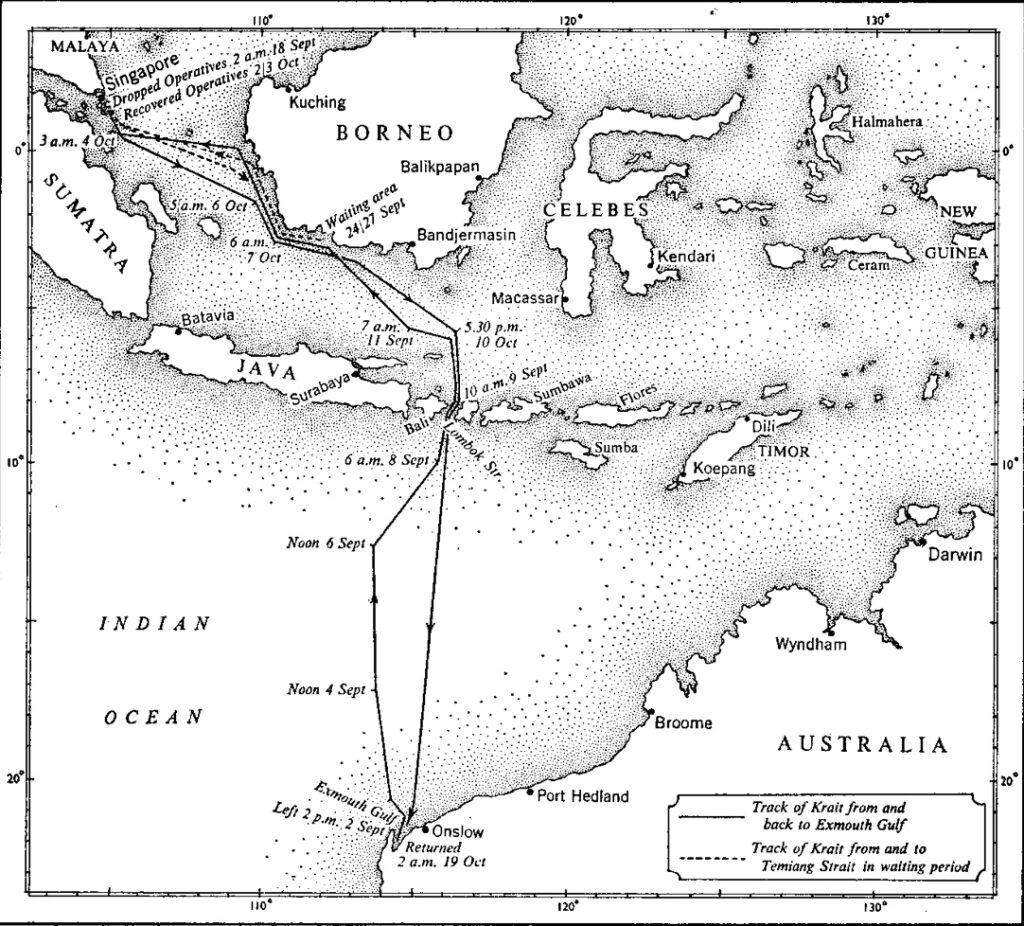

The Krait left on 1 September on their 4,000-kilometre trip to Singapore, but just 100 metres from the dock, her tail shaft broke, leaving the Krait to drift helplessly.

Fortunately, the US Base carried out the necessary repairs and they left the next day. The Krait was camouflaged as a Japanese fishing boat sailing the Japanese flag. It meant the men had to continually dye or stain their bodies nut-brown with a spirit-based make-up to give a darker, or at least more brindle or Asian complexion, and they wore sarongs to disguise themselves as local fishermen. While at sea, they had to experiment with the colouring, which failed at the first attempt.

“More black everywhere than on the person after an hour or two”, wrote one of the men. By 4 pm the next day, “the crew now resemble blackamoors, a more desperate looking crowd I have ever seen”.

As she headed north a fresh southerly produced an unpleasant sea on the port quarter. She did not perform well, displaying poor seaworthiness.

(Right) Subar Island. From this point the canoe parties departed for Singapore Harbour. AWM 300921.

After reaching the hazardous passage of Lombok Strait on 8 September, it took 24 hours to navigate it. At one stage, the vessel was forced backwards for an hour under strong currents. In the Java Sea, they carefully sailed along Borneo’s west coast to the Lingga Archipelago, anchoring off Pompong Island on 16 September. As dawn broke, they quickly realised the island was unsuitable, so they spent the next day zig-zagging from one deserted spot to another, looking for a place to land.

The next night, after seeing “the lights of Singapore glowing a mere 22 miles away”, they anchored off Panjang Island in the Rhio Archipelago, unloaded three two-man folboats and supplies, including the magnetic limpet mines. The Krait left to fill in time for two weeks around Borneo and rendezvous on the night of 1 October at Pompong Island. The commandos spent two days resting on Panjang Island.

Lyon led the six operatives. He was joined in the No. 1 kayak by Huston. No 2. Kayak was occupied by Davidson and Falls, and No. 3 kayak, Page and Jones. Each man wore a black, two-piece suit of waterproofed silk, two pairs of black cotton socks snd black sandshoes with reinforced soles, and was armed with a .38 revolver and one hundred rounds of ammunition. Each folboat carried food and water for a week, as well as the limpet mines.

They could only paddle at night to avoid detection. As the men paddled and island hopped to the harbour, they battled deadly tides, fierce storms, hostile ships and detection from the air. After an uncomfortable night in a sandfly-infested swamp on Bulan Island, they set up a forward post on uninhabited Dongas Island in a cave, where they could see into Keppel Harbour in Singapore. On the night of 24 September, they left Dongas Island to carry out their attack, but they had to abandon at 1 am because of a strong adverse tidal current and two folboats returned to Dongas Island. The other, headed by Lyon, had been in an accident with Davidson’s canoe and had steering problems. The current took Lyon and Huston eastwards where they reached a small island as daybreak broke and spent a wet day hiding. They met up with the others the next night.

The bad weather and strong tides made Dongas Island an unsuitable base to launch their attack. They decided that night to move their observation post west to Subar Island, just eight kilometres south of Singapore. It was 26 September and they had to attack that night to ensure they made it back to Pompong Island in time for their rendezvous with the Krait on 1 October.

After sunset on 26 September, under cover of darkness, the men paddled undetected into the busy Singapore port. Kayak No. 1 ran parallel to the well-lit up wharf area and placed two limpet mines on the engine room and propellor shaft of a large ship. Halfway through their work, Huston saw a man watching them intently from a porthole ten feet above them. He continued watching them until just before they left. Fortunately, he took no action and didn’t raise any suspicion.

Painting of Page and Jones in Kayak No. 3 attaching limpet mine on a ship’s hull in Singapore Harbour. Artist Denis Adams. AWM AT27649.

Kayak No. 2 attached limpet mines to three hulls of Japanese merchant ships on the Roads on the port side, away from the lights. Kayak No. 3 also put their mines on three ships, one at Bukum Island and the others in Keppel Harbour. They timed themselves by a clock on Victoria Hill that chimed the quarter hours. It took twenty minutes to approach, limpet and get away per ship.

The kayaks were clear of their targets when six mines detonated in the early hours on 27 September, damaging and destroying seven ships, including the sinking of Arare Maru, Kizan Maru and Hakusan Maru.

September 24 was the planned day for the attack, and those waiting on the Krait relied on any Japanese broadcast for news from Singapore. Finally, on 29 September, the Krait ran across the China Sea to the Lingga Archipelago and the planned rendezvous at Pompong Island, despite no news of the men. They were unsure if they were sailing into a trap.

After laying low on Dongas Island for a few days, the men paddled 80 kilometres to rendezvous with the Krait. One kayak approached the Krait soon after it anchored at Pompong Island. The other kayaks were there but could not find the ship during a fierce storm in the darkness. However, the Krait returned at 9 pm the next night and picked them up after midnight on 2 October.

The Krait successfully navigated the Temiang Strait for the last time, and they were very nervous as they approached Lombok Strait at 4 pm on 11 October. The men painted up again except Able Seaman Jones, who had a build “of a Jap and somewhat same colouring”. He was the hand waver on the deck to any inquisitive Japanese plane circling the ship.

Approaching the strait under near full moon, the Krait was driven hard into a fresh south-easterly, and short choppy sea, with tide rips in the northern narrows breaking over her.

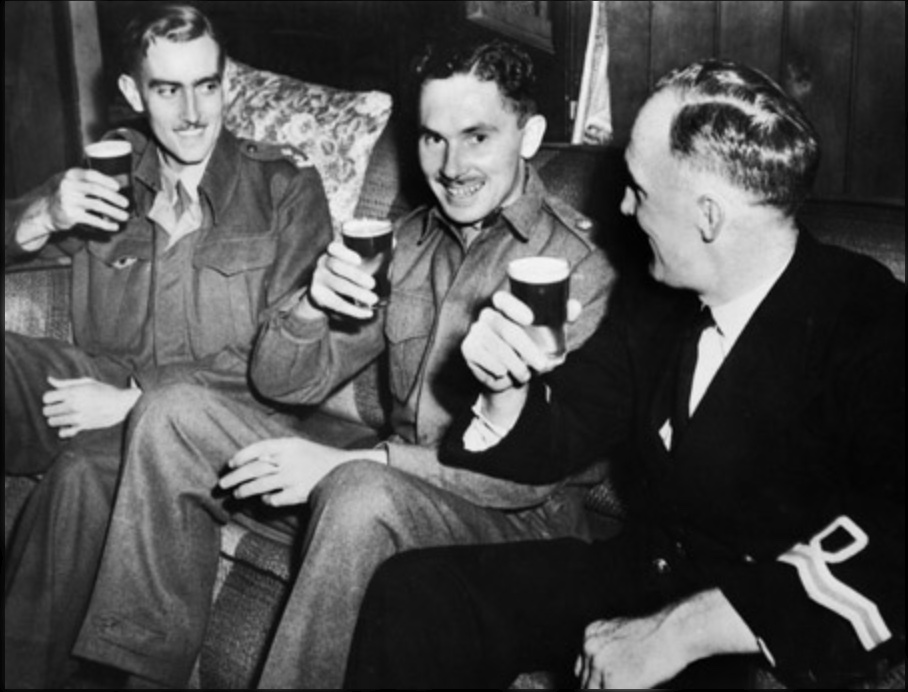

(Right) Page, Lyon and Davidson enjoying a beer together after Operation Jaywick.

Once inside the strait proper, the conditions were calm, but there was a bit of drama when a large naval patrol boat approached the bow about one hundred yards from the Lombok side. All hands were armed, and preparations were made for an evacuation. It was a modern destroyer around 300 feet long. It paced the Krait for about five minutes and then abruptly sheared off and left without using its searchlight or making any challenges.

Once they reached the main shipping channels in the Indian Ocean, they lowered their Japanese flag and became a proud fighting force instead of a stealthy fishing vessel. They successfully returned to Exmouth on 19 October 1943.

(Left) The canoeists celebrate in Brisbane after Operation Jaywick. L-R Falls, Davidson, Huston, Lyon, Jones and Page. AWM 134349.

Lyon and Page were flown to Melbourne for a debrief and then reunited with the rest of the crew in Brisbane to enjoy a couple of secret receptions in their honour, including one on Armistice Day where they were photographed together. It was impressed on every man that the success of future missions relied on Operation Jaywick remaining top secret.

Operation Jaywick was completed and would go down in wartime history as one of modern military history’s most daring and successful covert operations. Its tally of seven ships was more than twice as many Japanese ships (just three) sunk by British land-based aircraft in the entire war. It also ended up being the only completely successful operation mounted by SRD during the entire war.

Prime Minister Curtin recommended Lyon for the highest valour award – the Victoria Cross but it was turned down in London. Instead he was awarded the lesser Distinguished Service Order, as was Page.

After the War

The Krait was handed to the British Borneo Civil Affairs Unit at the end of World War II. After the war, the Krait operated out of Darwin as a coast watch and intelligence support vessel in Indonesia.

It was commissioned as HMAS Krait in 1944, and it witnessed the Japanese surrender at Ambon in September 1945.

She was bought by a British sawmiller for the Borneo timber trade and renamed Pedang. In the late 1950s, two Australians recognised her on a business-related trip. A public appeal followed, and the Krait Trust Fund was created to purchase the boat and return it to Australia in 1964.

(Right) Mrs Ivy Marsh, mother of Able Seaman Marsh, was given the honour of renaming MV Krait at Farm Cove, Sydney on 25 April 1964.

Fittingly, Ted Carse, Horrie Young, Joe Jones and Moss Berryman were part of the crew about the Krait when it was sailed from Brisbane to Sydney to commence its role as a museum ship.

The Krait spent time as a patrol, search and rescue boat for the Royal Volunteer Coastal Patrol and also for boating courses and school visits. It was transferred to the Australian War Memorial in 1985 and put in the care of the Sydney Maritime Museum to maintain and display it. In 1988, they loaned it to the Australian National Maritime Museum, who have managed the display, maintenance and restoration of MV Krait since then.

Tragically, being a wooden boat, she deteriorated while sitting in the water at the Australian National Maritime Museum’s Darling Harbour site in Sydney – an unassuming black timber fishing boat neglected and left to rot.

(Left) MV Krait after restoration.

A dedicated few bandied together in 2015 to set up an appeal to raise funds to save and restore the little boat with a significant past and display it as a permanent memorial to Australian Special Forces. They managed to raise $1.1 million, and plans are to build a custom-built expansion to the Museum’s Wharf 7 building to protect and display the boat.

It is a fitting memorial for a boat and crew who were part of a daring and brave operation against the Japanese during the war.

Ship specifications

| Length | 13.18 m on deck; 11.55 m waterline |

| Breadth | 4.45 m |

| Draught | 2.09 m |

| Displacement | 23.44 tonnes |

| Ballast | 3.37 tonnes |

| Sail | Gaff ketch, area 101.01 m2 with topsail |

The Krait was featured in an episode of Australian Story on ABC in June 2018. Also, in the early 1980s, Morris, Young and Jones appeared on an episode of This Is Your Life about the Krait.

If you want to read more about Operation Jaywick, there are many books and online resources. My favourite is a great book written by Ronald McKie called The Heroes.

Part 2 of this story will focus on the similar but fateful Operation Rimau, which involved a bigger crew of commandos, including Lyon, Davidson, Page, Marsh, Falls and Huston. Part 3 will reveal the fate of all the men involved in both Operations Jaywick and Rimau.

Remarkable story – thanks for your efforts!

Great story retold well, Robert.

I had seen the Krait at the maritime museum on various visits to Darling Harbour but never appreciated its history until moored on a yacht in Refuge Bay in 2016.

It’s a very beautiful spot with a small waterfall that descends from the cliff top to the beach.

There is a bronze plaque mounted on a large boulder on the beach at the base of the fall that commemorates Refuge Bay’s involvement in Jaywick.

It prompted me to look into the story which I did with growing astonishment at what they achieved.

A great story Robert. Well told as usual.

What a remarkable effort by these brave men. There is not enough recognition.

The two business men who recognised the Krait had both been in ZSU. One of these had trained only the other had served in operations.