The reason why humans prioritise bad news, according to Nobel Prize-winning behavioural psychologist Daniel Kahneman, is because “organisms that treat threats as more urgent than opportunities have a better chance to survive and reproduce”.

In the lead-up to this year’s Earth Day celebrations later this month, I thought it was timely to look closely at whether they are still relevant, given the dire predictions that have emanated from this day each year have never come to pass.

Earth Day was first celebrated in 1970, and many believe it was a defining moment for the birth of the modern environmental movement. The movement started in America when some 20 million people protested and demanded action to stop pollution, protect wildlife and preserve natural resources.

And it helps the hype when apocalyptic predictions are associated with each Earth Day celebration. In 1970, several scientists took advantage of the focus on the world’s problems and issued dire warnings. For example, ecologist Kenneth Watt told his audience, “we have about five more years at the outside to do something”. Harvard biologist George Wald estimated that “civilisation will end within 15 or 30 years unless immediate action is taken against problems facing mankind”. And Earth Day organiser, Denis Hayes famously said, “it is already too late to avoid mass starvation”.

Dr S. Dillon Ripley from the Smithsonian Institute also told us that in 25 years, somewhere between 75 and 80 per cent of all the species of living animals would be extinct. In 1975, entomologist Paul Ehrlich echoed Ripley’s sentiments when he said:

“…since more than nine-tenths of the original tropical rainforests will be removed in most areas within the next 30 years or so, it is expected that half of the organisms in these areas will vanish with it”.

Harrison Brown, a National Academy of Sciences scientist, published a chart that looked at metal reserves. He estimated we would run out of lead, zinc, tin, gold and silver by 1990 and copper by 2000. The green zealots must be thankful that Brown was way off the mark. Otherwise, the cherished net zero targets relying on those metals to provide renewable energy products would be impossible.

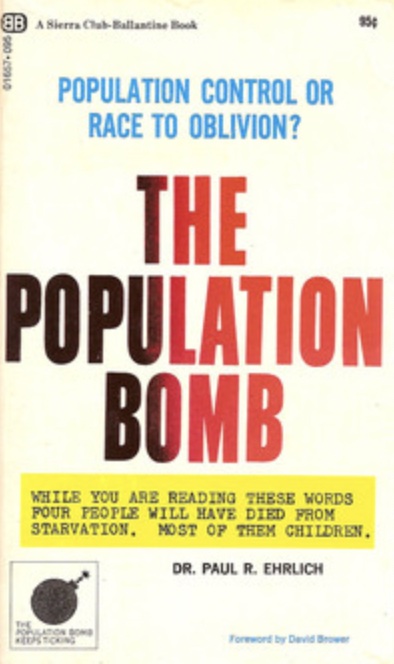

Perhaps the most strident doomster was Ehrlich. If you are old enough, you may recall the imminent threat of a global famine he claimed due to the “population bomb” explosion. Ehrlich confidently said at the time:

“Population will inevitably and completely outstrip whatever small increases in food supplies we make…the death rate will increase until at least 100-200 million people a year will be starving to death during the next ten years”.

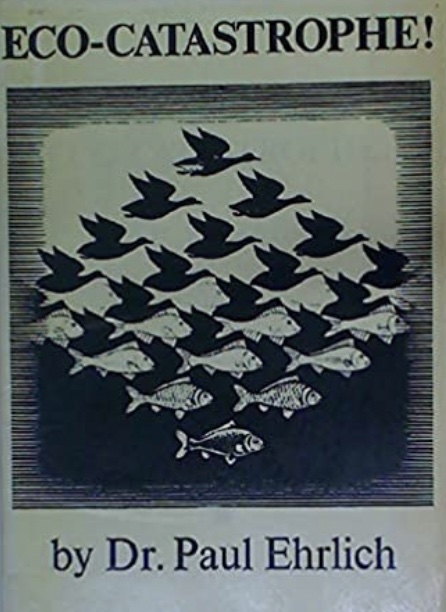

In his 1969 essay “Eco-Catastrophe”, he took aim at the bad guys, the “obtuse agriculturalists and economists”. Put simply, Ehrlich’s population bomb-induced “eco-catastrophe” was among many eco-disaster theories that were in vogue in the 1960s and 1970s.

Others were also happy to argue that trying to feed so many people would end in disaster.

For example, former U.S. Department of Agriculture agronomist and founder of the Worldwatch Institute Lester Brown argued in Scientific American:

“There is growing doubt that the agricultural ecosystem will be able to accommodate both the anticipated increase of the human population to seven billion by the end of the century and the universal desire of the world’s hungry for a better diet. The central question is no longer `Can we produce enough food?’ but `What are the environmental consequences of attempting to do so?‘”

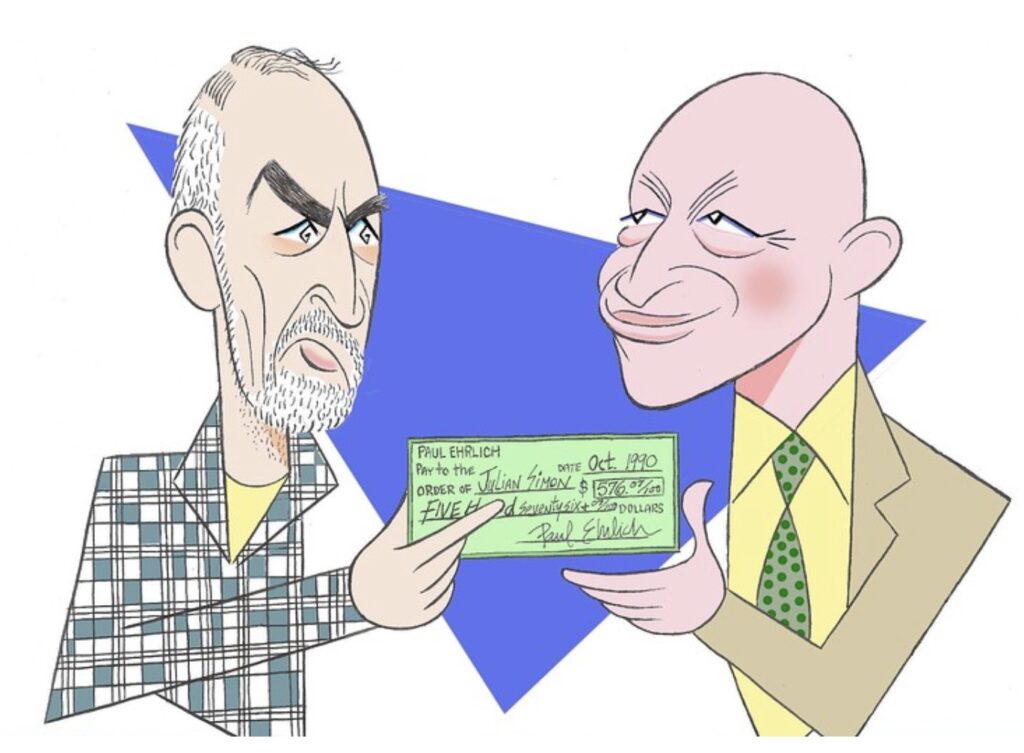

Unfortunately for Ehrlich, he is most known for being persistently wrong and never right. He famously lost a public scientific wager in 1980 with economist Julian Simon that the cost of five commodities to be selected by Ehrlich would increase over time. Simon initially agreed that population growth was bad for the Earth’s resources. However, after he carefully examined the data, he came to another view and saw that population growth was associated with economic improvement. The two debated back and forth until Simon proposed a bet. The bet covered the decade from September 1980 to 1990 for copper, chrome, nickel, tin and tungsten. In that time, the world’s population grew by more than 800 million, the largest increase in one decade in history. But by September 1990, the price of each of Ehrlich’s selected metals had fallen.

Pollution was another big issue in 1970. People were worried about smog in the cities and the poisoning of dangerous pesticides such as DDT. Watt told Time magazine:

“…at the present rate of nitrogen build-up, it’s only a matter of time before light will be filtered out of the atmosphere and none of our lands will be usable”.

I was too young then to appreciate these scary warnings, which is a good thing, as I reckon I would have been too traumatised and probably ended up on a cocktail of drugs to get through each day, which is apparently happening to kids today.

Earth Day has continued to be defined by gloomy prognostications. These days climate disaster predictions have overtaken Ehrlich’s failed population crisis and famines. And when the predictions fail, as all have inevitably done, new ones will be made without batting an eyelid. Take for example the darling girl of the UN from Sweden, Greta Thunberg. In 2018 she tweeted an article by gritpost.com (whose website no longer exists) detailing Harvard University professor James Anderson’s warning that humanity would cease to exist if the use of fossil fuels was not stopped within five years. The atmospheric chemistry expert also argued there would be “essentially zero” ice left in the Arctic by 2022. In March 2023, after it was obvious Anderson’s claims were wrong, Greta was caught deleting her tweet after Anderson’s claims did not happen – the world was not at an end and the Arctic ice still exists. I guess in these more modern times it is easier to try and eliminate your faux pas quietly, something Ehrlich et al couldn’t do back in their day.

A study in the International Journal of Global Warming assessed 79 predictions of climate armageddon since the first Earth Day in 1970. The authors found that over 60 per cent of the predictions had already expired by 2020. Around 43 per cent of these predictions never allowed for uncertainty about the dates of the end of the world. The average time horizon for climate apocalypse was about 20 years, and little has changed over the past half-century.

Of course, five decades later, the world hasn’t yet ended. But, I argue that, if anything, Earth’s future looks promising. I think it is high time we took the glass half full mentality. I can see the smirks from my readers and hear them mutter, “what rock have been hiding under – what about all the evidence that proves the climate emergency we are facing today?”

Indeed, what about it? Why are the cataclysmic predictions that we will fry if CO2 levels continue an upward trajectory any different from other, yet similar, failed doomsday warnings issued each Earth Day for the last 50 years?

Why doesn’t Earth Day ever celebrate huge environmental gains over the last 30 years? By examining some of the first predictions of doom, many positives go unreported.

But what if the world was a better place to live now than 50 years ago? Wouldn’t it be great if the world’s population trebled beyond Ehrlich’s level of complete annihilation and still managed to feed itself and have plenty left over? Well the good news is it has, and it has been largely thanks to a plant breeder who studied forestry.

Not many people may have heard of American Norman Bourlag. He exemplifies the concept of human endeavour to adapt and innovate to improve living conditions – something you never hear acknowledged each Earth Day in contrast to the polemic offered by Ehrlich and his mates. Bourlag is credited with saving a billion people from starvation by reversing food shortages in India and Pakistan, at the same time that Ehrlich and Brown were hogging the limelight with their false alarmism.

By developing the high yield, low pesticide dwarf wheat strain, Bourlag initiated the expansion of food production faster than the growth of human populations, thus averting the mass starvation that Ehrlich widely predicted in “The Population Bomb”.

For example, thanks to Bourlag, India’s annual wheat production has increased by 1,020 per cent since 1965, from 10 million tons to 112 million tons. During that period, India’s population increased by 180 per cent, from 500 million to 1.45 billion. Therefore, every one per cent increase in population corresponded to a 5.66 per cent increase in wheat production. This is the opposite to what Ehrlich predicted.

The example of producing more food from less land in Australia was highlighted in my blog on the Wheatbelt in Western Australia.

Since Bourlag’s work, no dust bowl conditions from the 1930s in mid-west America have reoccurred, despite climate scientists reminding us every summer that it is the hottest, driest ever experienced.

We should be celebrating the ingenuity of Bourlag that has allowed us to reduce the poverty rate despite the world’s population reaching eight billion people. As Gale Pooley recently wrote, “while Ehrlich wanted to sterilize Indians in order to control population growth, Borlaug taught them how to feed themselves and export their surplus production”.

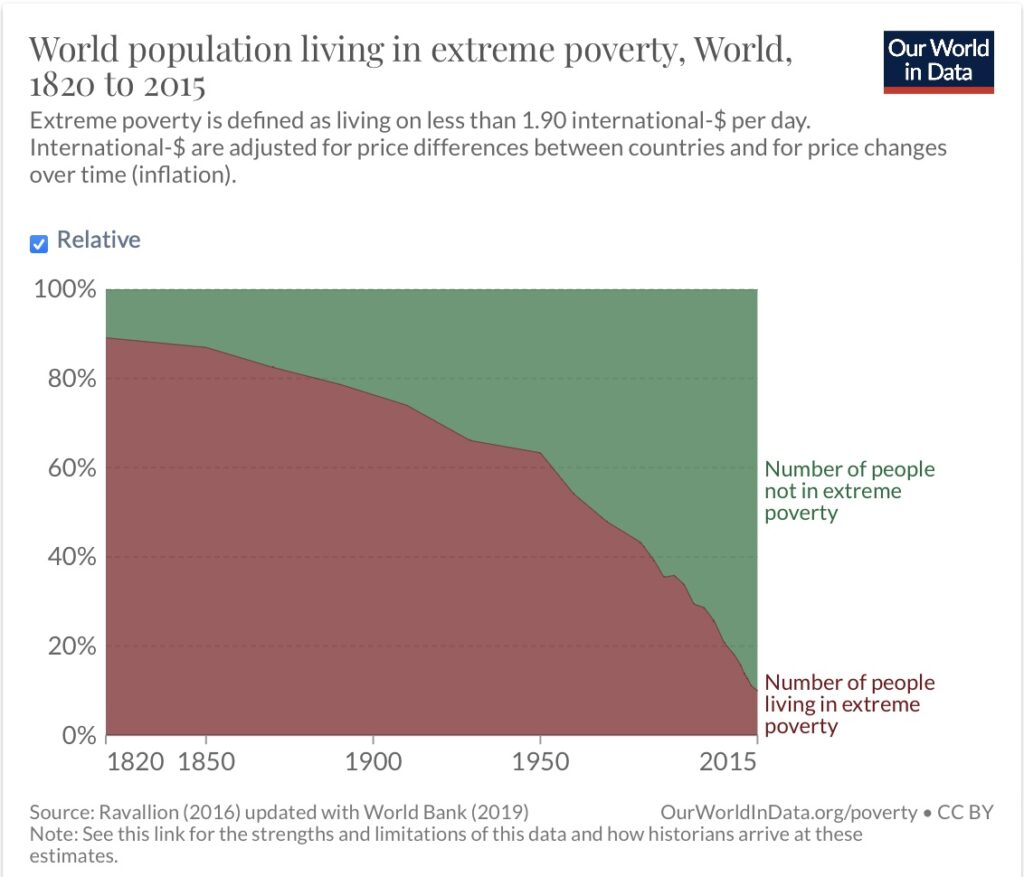

While too many people still remain poor and hungry, we have not seen mass starvation on the scale predicted in the last four decades. Instead we have seen poverty levels in developing countries drop to single digit figures and in developed countries, obesity is on the rise.

The only continent yet to benefit from Bourlag’s work is Africa, as environmental groups have successfully campaigned against introducing high-yield farming techniques. Opponents argue that inorganic fertilisers and controlled irrigation will bring environmental problems, despite the continent’s depletion from existing slash and burn agricultural practices. The need to feed the malnourished is conveniently overlooked by the chattering class as they hoe into their daily smashed avacado while sipping their double decaf soy latte surrounded by concrete and bitumen.

I believe Associate Professor Pierre Desrochers best sums up the annual charade of needless despair:

“From the first Earth Day to the present one, activists’ fears have been largely driven by computer models that have warned us that catastrophe is only about 10 years away. Unlike the first Earth Day when activists invoked a wide array of problems to justify drastic anti-growth policies, however, recent calls to achieve net zero emissions through build back greener initiatives are entirely based on catastrophic climate scenarios developed by modelers with strong environmentalist leanings. Some historical perspective on this topic nevertheless suggests that cooler heads should perhaps prevail.”

I put this scenario to readers to think about when Earth Day comes around later this month. Instead of believing the inevitable virtue-signalling environmental hustlers that will trot out the predictable gloom and doom claims, consider instead precisely what sort of conditions the inhabitants of Earth enjoy today.

Compared to 1970, the Earth is much cleaner, with less hunger and malnutrition, less poverty, longer life expectancy, and lower mineral and metal prices. In addition, cyclones, tornadoes, floods and droughts are not getting worse, cereal and food supplies have increased, and income levels have improved.

Since the 1920s, the global death rate from extreme weather events has fallen by a staggering 98.89 per cent, despite a tripling of the world’s population.

But, of course, empirical data means little when it comes to environmental pessimism. The Earth Day organisation boasts “it is the world’s largest recruiter to the environmental movement, working with more than 75,000 partners in over 190 countries to drive positive action for our planet”. However, that positive action is under question.

Take for example the excellent documentary film by Michael Moore called Planet of the Humans that was released free to the public on You Tube on the 50th celebration of Earth Day in 2020. It provides evidence that industrial wind farms, solar farms, biomass, and biofuels, promoted by the Earth Day organisation, many activists and indeed politicians of most developed countries to achieve Net Zero, are impacting negatively on natural environments. Therefore the organisation is actually struggling to meet its aims.

Isn’t it time that Earth Day celebrations shift from an indulgent exercise in fabrication to a recognition of the outstanding achievements in human history? We live in the best of times, and the empirical data proves this.

Despite the exaggerated and downright wrong predictions, foresters don’t mind celebrating Earth Day as it is an opportunity to showcase the long-term protection of the forest resources through active management of forest health, growth, harvest and regeneration. Foresters have long embraced the concept of balanced, perpetual use and protection of forests.

Earth Day is a good time for us to remind others of the role of sustainable forest stewardship in enhancing our economy, environment, and social well-being.

So, on Earth Day later this month, why not take the time to thank foresters and loggers who help keep our forests and rural communities healthy while also providing us with a wide variety of products made from renewable, recyclable, sustainable wood?

And while you are at it, write a short note to your state premier to remind them of the value of balanced forest management before they contemplate ending the harvesting of native forest trees for good.

I frankly had forgotten all about Paul Ehrlich!

His Eco-Catastrophe epistle was read by many at Forestry School.

Makes you wonder if he selected his own peers to review his Doctorate degree!

G’day Robert.

I congratulate you on your latest article on Earth Day.

We live in a world community that for the majority, accept no responsibility for their actions, that shows a society willing to endorse selfishness over responsibility.

Reading Vic Jurskis’ and Ian Plimer’s books has taught me a lot. Not just the experience knowledge in their books, but how they go into detail of each point they make.

Reading papers produced under the guise of meeting scientific research by the academic qualifications used to supposedly give credibility, Vic and Ian have taught me how to in a few paragraphs, pick a fraud.

Climate change, logging, farming, mining are mentioned instead of the evidence of the evaluatations to meet their claims.

A well researched piece Robert on a topical polemic.

“Limits to Growth” published in 1972, by the Club of Rome, gave every peddler of imminent global catastrophe a base for hysterical predictions.

This constant shrill of doomsday finites continues in expediential mode to the present day. Persistent puerile persuasions flood the gullible media and classrooms of the tired tiered education system. The gold medal standard has been provided of late by the IPCC and its religious disciples.

Australia has its own Nostradamus perpetual failures, including, but not limited to, Flannery, Swann, Misha Ketchell, and Lindenmayer. These prima donners have a history of dire predictions on all manner of natural systems. Their documented inconsistencies and false predictions have never curtailed their star appeal appearances on the chat circuit.

Australia also has its own agricultural guru whose science provided the basis for the introduction of drought resistant wheat varieties for use on dry land farming enterprises, Distinguished Professor Graham Farquhar AO, FAA, FRS, NAS.