Introduction

The summer of 1933-34 was very dry across most of Australia, including Tasmania. It began a pronounced drought period that lasted until early 1939.

Victoria had significant bushfires in 1932. “Red Tuesday” on 19 January saw many fires in almost every part of the state, particularly West Gippsland, where nine people died. In the Dandenong Ranges, a fire was close to Olinda and Sassafras. Many residents hurriedly removed their possessions and furniture to the roadside, fearing the ominous threat. About 100 firefighters, mainly residents, managed to bring the fire under control after a few hours of strenuous work. The previous night there were reports of many fires in the Ranges. Montrose was under threat the following Saturday evening, where the fire “tore down the hillside” from Mount Dandenong, fanned by a high wind. Many acres of forest were burnt in the fires, and several weekend homes were destroyed.

In October 1933, more fires in the Dandenong Ranges burnt several areas, including Sherbrooke Forest, until a cool change eased the threat. Erica was surrounded by fire in the Victorian Gippsland region, and many sawmills were threatened. There were also significant fires in the Donna Buang forests near Warburton. Bush burnt for several days surrounding Anglesea and swept towards the town, but a wind change averted any disaster.

In February 1934, another Victorian fire ran from Gellibrand River to the Beech Forest and onto Apollo Bay, their most disastrous fire in many years. Twelve houses were destroyed. There were also fires at Hepburn Springs. Parts of Victoria experienced a period of dry, hot weather in early autumn 1934, with temperatures in the late 30s for five consecutive days with strong northerly winds. Fires started daily in the Dandenong Ranges. The first fire was at Tecoma. Another at Upwey, from a burn-off by a railway gang, roared down the valley. Another fire started in the national park at Upper Fern Tree Gully and headed towards Devil’s Elbow. Not long after, another fire started at Tremont. Around 300 firefighters battled the blazes to protect houses. Remarkably only two houses were burnt down.

In March 1934, a bushfire tragedy occurred in the Upper Sturt locality in the Coromandel Valley. The outbreak had begun early in the morning, swept an area of 20 square miles and was fought by 400 men battling fires for nearly a week in intense heat. A 75 year-old resident of Coromandel Valley was trapped in flames at Ackland’s Hill, east of Coromandel Valley, and burnt to death.

But the summer of 1933-34 unleashed its fury of hell in Tasmania. From late December 1933 to the end of February 1934, Tasmania felt the full brunt of the drought conditions when fires raged across most of the island. There were major fires through the Florentine and Derwent Valleys in the south, east, north-east and west coast areas. The worst was in the south, where massive fires tore through large areas of state forest, threatening and overwhelming small settlements.

However, this blog will focus on the fires in most of the native forests in the north-west of the state that summer.

Van Diemen’s Land Company fires before 1934

The records of fires on Surrey and Hampshire Hills are limited from the correspondence of the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s (VDL Co.) Chief Agents and in the newspapers, mainly because the assets and people affected were minimal. Nevertheless, there were some notable fires.

In the late 1880s, Chief Agent James Norton Smith wrote about some problems with fires spreading from neighbouring farms onto the Emu Bay estate. On a hot day in January 1887, a locomotive started a fire to 40 acres of scrub on land tenants had just cleared. As a result, a wildfire swept over the Emu Bay Estate in February, killing the grass and forcing cattle to be sent to Woolnorth for sufficient feed. Dense smoke covered the district for many days and it was even reported that snakes were compelled to “quit their haunts to escape the fires”.

A large fire on grassed land at the Ridgley farm was started by a spark from a passing locomotive on the railway in early March 1892. Under a strong wind, it spread rapidly, affecting about 700 acres. Unfortunately, the fire followed the ravages of the caterpillar on the newly sown pasture, causing a shortage of feed until the autumn rains arrived.

February 1898 was the culmination of a dry summer in the north-west. A wildfire from a neighbouring property entered the Highclere farm at the 13-Mile, fanned by a strong south-westerly wind. It continued into a section of the forest onto Ridgley through “the length and breadth of the Ridgley farm”. As a result, about 570 acres of cleared scrub adjoining the Ridgley farm to the west were burnt. However, it reportedly facilitated the sowing of improved pasture.

Bushfires prevalent over the VDL Co’s Emu Bay Estate during the last fortnight in January 1906, also swept over their estate at West Ridgley, causing considerable damage. The fires started in the nearby Guide Bush the previous week. A six-hour strong wind change carried the blazes out of the bush across the Guide River and through the whole of the Ridgley lands consisting mainly of ex-myrtle rainforest that had been cleared. The VDL Co. had to move 600 head of cattle to safety.

The cottage occupied by tenant Timothy Deacon was burnt, and the loss of pasture and fences affected other tenants of these areas. The fire burnt another 200 acres at East Ridgley. A little rain on 12 February helped stop the progress of the fires. On Saturday, 17 February, over 11 millimetres of rain saved the East Ridgley farm from being “absolutely destroyed as a grazing run for six months”. However, over 1,000 acres of burnt pasture had to be resown, and the VDL Co. were forced to move their cattle to Woolnorth. A visitor from Hobart to the north-west coast reported that he had not seen “clear sunshine” for ten days because of the smoke from numerous bushfires across the district. Another wildfire burnt a 30-acre patch of heavily timbered land at the 27-Mile a month later. Chief Agent Andrew McGaw described it as a good fire in the scrubbed section.

There were several fires in January 1913 throughout the north-west. A fire on the Mooreville Road destroyed a five-roomed cottage tenanted by Mr J Saunders and owned by the VDL Co.

Fierce fires tore across the north-west during February 1915, including Hampshire. While the impacts on the VDL Co. land were minimal, the worst hit areas were Natone, where a father of seven died trying to escape the flames, and Trowutta, where a mother died saving the lives of her two children. A South Australian newspaper reported the fires were “the most devastating bushfires ever known in Tasmania sweeping over the northwest coast and other districts. The extent of the devastation cannot be over-estimated”.

The summer of 1918-19 was hot and dry. In February there were fires at Riana and the Emu Bay Estate around Burnie, as well as the Ridgley district. Welcome rains in the north-west on 16 February doused the fires and helped with pasture growth. The following February, there were fires in the Oonah and Ridgley areas, with fires at East Ridgley and Mooreville Road burnt fiercely through bushland. The VDL Co. didn’t report any losses from these fires.

The VDL Co. faced destructive fires again in early 1926. Fierce fires tore through the north-west coastal hinterland. On 7 January, there was a fire in the myrtle forest near the 23-Mile. Another fire destroyed timber piles at an idle sawmill on Holloway’s property and surrounded James Nolan’s house at the 16-Mile. It continued for a month and flared up again on 6 February, a hot and oppressive day with strong winds. Aided by a strong south-westerly wind, the fire grew to over 2,500 hectares and was fanned towards Hampshire, threatening several farmhouses.

The postmaster, Christian Stitz, had difficulty saving his house from the fire. The superintendent, sergeant and troopers of the police force at Burnie, along with volunteers, drove to Hampshire to assist in fighting the fires. Their trip was made difficult by the thick smoke making visibility hazardous. The Holloway house caught fire but was eventually saved. One of the volunteers, Jack Fidler, an employee of the VDL Co., “had a trying time and is still suffering from the effects of the heat”. Embers from the fire reached Burnie and covered the town in dense smoke. A day later, the winds died, aiding firefighting efforts, and some rain helped “wipe out all danger”.

On 28 December 1931, travellers on the West Coast train reported massive fires between Burnie and Guildford during the night. The section most affected was between Hampshire and Highclere. The fires reached within a few feet of the railway line, and because of the dense smoke and “fierce flames, the rail motor from Burnie to Waratah was considerably delayed on the journey from Highclere to Guildford Junction”. Thick clouds of smoke hung over the Burnie all day, and several small bushfires broke out in the Emu River Valley and at Round Hill and Chasm Brook on the coast.

In February 1933, there were fires surrounding Burnie, including at Round Hill. One of the fires burnt out the grass in the VDL Co’s. paddock on the Surrey Hills Road destroying the boundary fence.

The great fires of the north-west

In January and February 1934, bushfires raged throughout the state. 1933 was a dry year for Tasmania. Practically all of Tasmania had below-average rain and some areas, like the north-east, the north-west, the Central Highlands, and pockets on the west coast, had very much below-average rainfall. The VDL Co. recorded a dry and cool spring for the landholdings. A good rain event at the end of November brought some grass growth, but it was short-lived as caterpillars destroyed the pastures, and the weather remained dry into summer. The weather was unusually hot for the north-west and the whole region was very dry.

Bushfires broke out on the West Coast in late December 1933 after an extended period of dry weather. Passengers on the rail journey from Burnie reported that “fires had been raging in extensive areas between Guildford Junction and Strahan” and the Zeehan District. They included fires burning near the Mount Lyell Railway. A cool change and light rain eased the situation momentarily.

The 6 January was a hot and oppressive day with strong south-westerly winds. Large fires swept through the forests of the north-west coastal hinterland and the west coast. A fire in the Nelson Valley about 14 miles from Queenstown threatened several huts occupied by woodcutters, destroying one hundred tonnes of firewood that had been cut and stacked ready for delivery to Queenstown. Flare ups of the previous fires in the surrounding Mount Lyell district were raging again.

The 15 January was one of the hottest days recorded for Zeehan for many years, and several bushfires were uncontained near the town. The following day, hot weather in the Forth River Valley saw fires race through the Staverton district, destroy one house and threaten many others. The smoke was so thick it obscured the sun, and embers from the fires fell on nearby Sheffield. A resident of Wilmot, upon reaching the coast, reported a big fire raging at the back of the township and feared the wind would make it threaten farms in the area. The Lorinna school was burnt down. The Emu Bay Railway Company’s (EBR Co.) rail motor had to pass through fires on both sides of the line between the 29-Mile and 20-Mile on its journey from Zeehan that night.

A terrible day

The 16 January 1934 was one of the worst days of the fire season. Tragic reports about the devastating effects of the bushfires across the north-west emerged. Twelve houses had already been destroyed – four on the Emu Bay Railway near Hampshire the day before. The Hampshire residents who lost their homes were Herbert Gillie, William Ellis, Roy Nothrop and Mortimer Ellis. All of Eric Ballantyne’s farm buildings were burnt down. Hampshire that afternoon was encircled by a wall of flame.

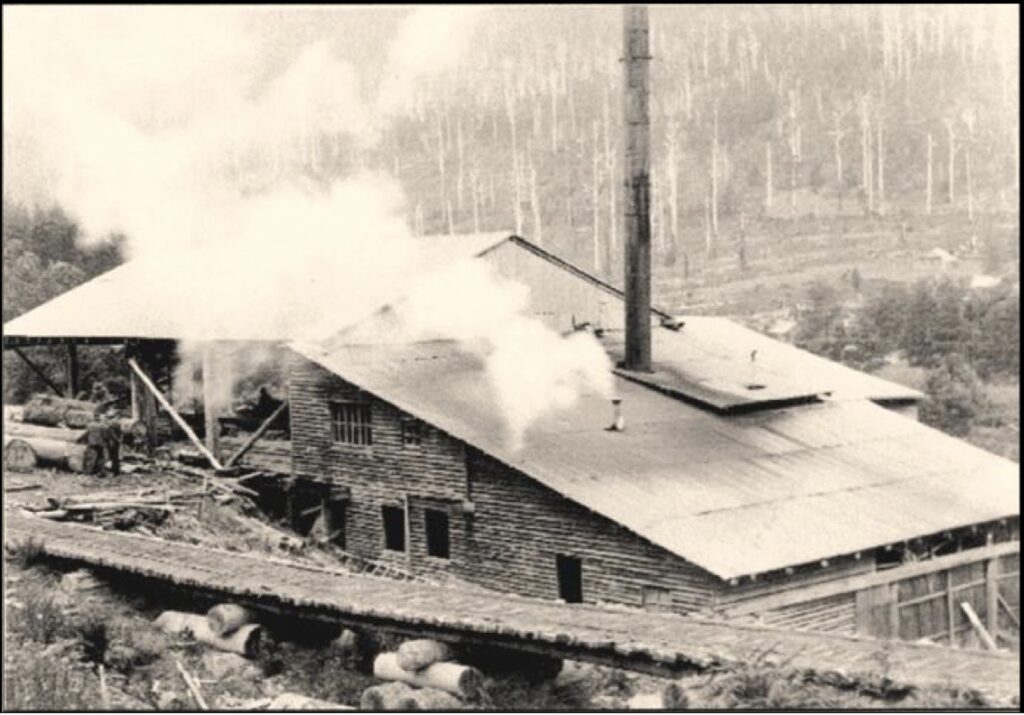

The employees of Cumming Bros.’ sawmill at the 25-Mile at Ringwood fought away a threatening fire. As a result, the chaff house, containing several tons of chaff and one of the workman’s huts, were destroyed. Also, timber near the mill and about one and a half miles of their bush tramway was damaged.

A fire swept through the Campbell Ranges and descended onto Takone, destroying Allan Taylor’s sawmill, eight homes belonging to the mill workers, a stable blacksmith’s shop, and his big lorry.

It started at 9:00 am and descended on the sawmilling community fanned by strong winds. Women and children barely had time to escape:

“With the exception of the clothes they wore, they lost their all. Volunteers went from Yolla and Wynyard, and all worked strenuously to fight the flames. Eight horses were rescued from a stable just in time, and an eye witness stated that the flames were leaping 30. feet high. Dense smoke enveloped the countryside and Wynyard”.

A strong north-westerly wind around 4:30 pm brought the flank of the fire into furious flight. That night, the Takone postmaster reported the fire was raging only a mile from the town and could be “plainly heard as it roared through the bush”.

Bushfires also started in the Mole Creek and Western Creek areas, Loongana and the Black Bluff Range. Mole Creek was under a “smoke haze so thick that visibility was confined to a hundred yards”. Residents reported “showers of cinders, consisting of leaves from the trees in the burning areas, falling on the township”. Mr Hill of Kentish, with a party of three prospectors, who had their car burnt, were lucky to escape with their lives and only reached safety after following the riverbed for some miles. At Natone, Alan Hilder’s sawmill and buildings were destroyed. Firefighters managed to save Cumming Brother’s sawmill at Mawbanna and the bridge over the Duck River.

Practically the whole of the forested lands in the back country behind Table Cape, including Takone, burnt that day. The fire also raced up the Flowerdale River gorge overwhelming the small settlement of Preolenna after leaving the forests to claim the cleared areas on the ridge. The Wynyard Sawmilling Company’s Exclusive Forest Permit area near Preolenna was completely burnt out.

The rest of January

A wind change on 19 January turned the fires back over their previous course, providing much-needed relief for the firefighters. The worst areas were at Takone and Preolenna, and while the fires remained uncontained, they were not spreading. However, a fire threatened some houses north of Hampshire in the afternoon. In the Burnie Municipality, rain eased the threat of the fires. Light rain commenced that night for a couple of hours. However, the next day was one of the hottest experienced that summer, and residents feared fresh fire outbreaks. Reports from Natone, Upper Natone and Hampshire, indicated the fires had died down, but firefighters were alert for further breakouts in the hot weather.

Strong southerly winds on 20 January fanned a bushfire through the timbered country between Sisters Creek and Roger River. The bridge over Crayfish Creek was destroyed on the main coast road. A huge fire travelled towards the Wynyard Sawmilling Company sawmill at Oonah on the Waratah-Wynyard Road, forcing employees and their families to evacuate. Luckily the mill was saved despite losing a shed and its contents, including a motor car and cycle.

The fires that had raged in the Burnie back districts over the previous week were rekindled into new activity on this day.

“The roar of the flames yesterday could be heard at least a mile away, while flying sparks were lighting the bush over 20 chains in advance of the main body of fire”.

The areas worst hit were Snowden Plains, near Oonah and Tewkesbury. The fires brought down several large trees across the road between Tewkesbury and Oonah. There were reports that the fire was so hot the water in the Douglas River killed hundreds of fish.

Fires were lively over the weekend (20-21 January) in many areas. At Hampshire, they damaged more fences, pasture, and potato crops. At Ridgley, fires approached the town on Saturday afternoon, causing similar damage. Fires were still burning at Newhaven and the Dip River near Montumana. One burnt Mackay’s sawmill, together with huts and buildings. A huge stack of blackwood logs containing about 40,000 super feet was also burnt. The bridge over the Black River on the road from Newhaven to Mawbanna was severely burnt. Residents at Lapoinya had an anxious time preventing the fires from damaging homes. A strong easterly wind drove the fires from Preolenna towards them and ran through the nearby forests, severely damaging the trees.

Tuesday, 23 January, finally provided a day of respite allowing the fires to smoulder under an easterly wind. The air cleared the smoke only to reveal desolate scenes. From Natone through to Smithton, there were blackened scenes where the fires had crowned through the forests killing large swathes of trees and causing considerable damage to the commercial stands. The fires came within only a few metres of farmhouses and settlements in many places. It was a miracle that many of those were not wiped out. There were also fires in the Cethana area, which threatened farms, with one house burnt down. And near Irishtown, firefighters fought hard to save Alf Sharman’s home on Sunday. Several sawmills in the area were in imminent danger, but the efforts of the firefighters protected them from the carnage. Finally, many farms near Trowutta also suffered damage from a raging fire.

The VDL Co. were fortunate that their Emu Bay Estate grasslands escaped the fires, despite a few farmers in the Emu Bay district losing all their pasture and suffered damaged fences, and in some cases, houses and buildings burnt down. However, they did suffer damage at Ringwood, where the only two buildings left were burnt out. VDL Co. Chief Agent Andrew McGaw said no rain had fallen since the 9 January, and even then, that was only 7 millimetres.

The smoke from the numerous fires that weekend blew across the Bass Strait, enveloping southern Victoria in smoke. As an exhausting month of fires ended, they blew up near Strahan on a very hot day on 29 January. Strong northerly winds reactivated fires that had been smouldering in the surrounding hills for weeks. Fortunately, that night there was a cool change with a lightning storm followed by rain.

February – the turmoil continues

Sunday, 4 February saw renewed fire activity in several places. A fire started on the Flowerdale River between Sisters Creek and Moorleah, and with a strong wind blowing, it soon spread, endangering a few homes. Sawmills owned by Thomas Hilder and Frank Fenton were under threat. A major fire at Mengha caused havoc for over ten days. Fanned by a strong north-easterly wind, it burnt out recently scrubbed properties with timber stacks waiting to burn. Locals reported flames 100 feet in height. The school and post office were threatened, where heaps of firewood in the schoolyard caught alight.

On 7 February, fires that had been smouldering in the timbered country behind Burnie flared up again. Burnie was once again covered in a dense cloud of smoke in the morning, which had drifted from fires in the Tewkesbury and South Riana districts. Fortunately, there was little wind, and the fires didn’t spread far. The smoke cleared away in the afternoon. However, there were also fresh outbreaks in the Takone and Henrietta areas.

Bush fires rekindled in the Britton’s Swamp and Christmas Hills districts. In the former, Britton Brother’s sawmill and timber yards were threatened. Again, the relatively mild wind conditions were favourable to firefighters. The next day saw one or two small fires just south of Hampshire and in the gorges near Natone. There was considerable damage to forests in the West Calder area, and a fire in the Jesse Gorge near Preolenna continued to burn.

The winds were strong on the west coast on the night of 7 February. They fanned fires which had been smouldering around Mount Lyell. However, while the Mount Lyell Mining Company’s hydroelectric plant at Lake Margaret and the transmission line to Queenstown were at one stage under threat, the fires were kept under control, and the power supply remained uninterrupted. Other fires were at Howards Plains, Sedgewick Valley below the Comstock settlement and along the Mount Lyell railway to Regatta Point.

A fierce north-westerly gale drove a fire that had been burning for weeks in the Henty area north of Strahan. It quickly spread, jumping from hilltop to hilltop towards Strahan. Many burnt trees fell over the Mount Lyell Mining Company’s pipeline, which supplied Regatta Point and the wharf with water, cutting off supply. The bridge across the Little Henty River was destroyed, severing the rail service to Zeehan. Two houses were burnt down, and fortunately, the Forestry Commission pine plantation was saved, thanks mainly to the efforts of local forestry officer, Mr H. Bracken.

The Abt Railway was severely damaged in places. The area between Rinadeena to beyond Lynchford was affected, with several bridges near Dubbil Barril damaged. In addition, signal boxes at Rinadeena and Hall’s Creek were destroyed. Fires spread in the Crotty area as well, affecting prospector camps.

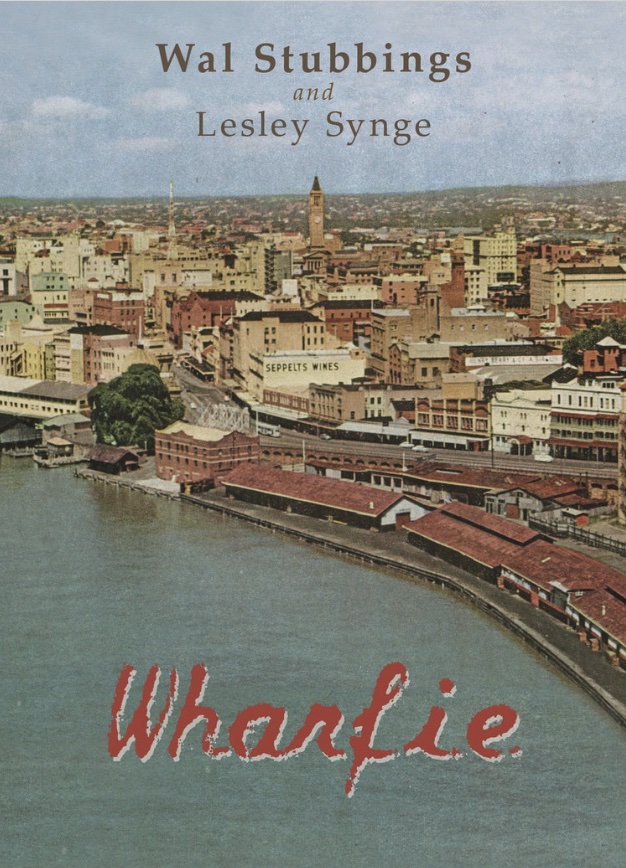

Several competitors for the annual Queenstown Eight Hour Day Sports Carnival on 10 February walked from Zeehan and Strahan for the event because train services were cancelled due to the fires. Young Wal Stubbings, the son of a timber getter on the West Coast, walked from Strahan to Queenstown along the Abt Railway line with his two brothers and friend Jack Morrison. Unfortunately, Jack sustained head injuries when he fell from one of the bridges damaged by the fires. Wal gave a vivid account of the fires in his and Lesley Synge’s biography “Wharfie”:

“We set out on Friday afternoon with our competition axes on our shoulders and the bushfires all around us. Bang! Bang! came the sound of the trees exploding. ‘The myrtles are going off like cannons!’ Ken, his brother exclaimed”.

The boys made it into Queenstown at midnight and competed in the woodchopping events the next day. Despite his injury, Jack took part and finished third in his heat. Wal Stubbings and his brothers were also involved in a dramatic rescue at Wheldon’s property on the Thursday before the Carnival. With a fire threatening the farmhouse, they rushed inside to pick up the children and hustle the women before the fire overwhelmed the building.

There were new outbreaks of fires on the VDL Co.’s Emu Bay Estate. One of those was in their forested land south of Oonah Road, east of Tewkesbury, threatening pasture country at West Ridgley. Fires were also in the Circular Head Estate, damaging fencing.

McGaw was scathing about the fires started by railway engines used by the EBR Co. He believed that the EBR Co. managers had been careless in the past regarding fires caused by their engines. After threatening to make claims of any damages against the EBR Co., McGaw pushed for the installation of spark arrestors. Still, the manager of the EBR Co., James Stirling, resisted. He claimed that they reduced the haulage power of the locomotives, particularly on steep grades, plus he insisted they were of little value. However, McGaw persisted in his arguments writing a strongly worded letter to Stirling, details of which he relayed to the Court of Directors in London:

“Mr Stirling was somewhat hurt that I wrote so strongly. The weather was so dry at the time with strong hot winds that I feared very serious fires on our land and I felt there should be absolute frankness so that I should not appear to be condoning what I considered to be unjustifiable indifference to the interests of land owners. The Railway Company has already received a number of claims for damage by fire caused by their locomotives”.

Stirling relented and immediately installed the spark arrestors. However, fires were still started by the locomotive engines. The problem wasn’t just on the Emu Bay Railway. The Tasmanian Government Railway line in the Derwent Valley was alleged to have started fires.

Monday, 12 February, saw more strong winds, which gave the smouldering fires a new lease of life. A massive fire in the Inglis River Valley above the crossroad from Calder to Preolenna became an inferno, racing through many properties. Thankfully, only one house at Lapoinya was destroyed. However, fires ran through the unsettled forested country south of Upper Natone while the Tewkesbury fire raged again, threatening the newly established Agricultural Research Station.

Heavy rain started falling on the West Coast on 14 February, easing the fire threat around Strahan and Queenstown. However, fires continued elsewhere in the north-west. The inhabitants of Sheffield were provided with a spectacle at night when fires travelled up the steep slopes of Mt Roland. There was also another devastating fire at Lapoinya on 16 February.

Finally, up to about an inch of rain across the north-west on 28 February and put out all smouldering fires. In early March, however, a new fire at Parrawe killed livestock. Bawer and Mason’s sawmill and stables were destroyed together with three huts. It nearly burnt down the houses of Thomas Lancaster and Ivan Smith after they caught alight during the blaze. Another fire burnt in forests on the southern side of the Hellyer Gorge.

The aftermath

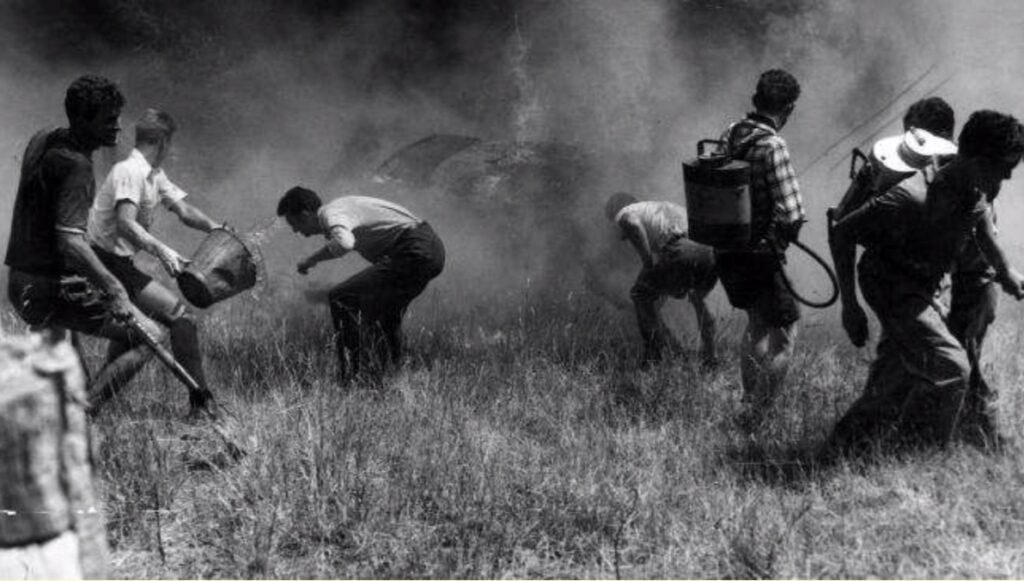

Not much native forest in the north-west was spared from the 1934 fires. Firefighting capabilities in those days were very rudimentary, where local firefighters were the residents and were assisted by police officers. There were no fire tankers and no aerial water bombers. Nothing was done to contain the fires in the forests. There was no infrastructure set up to attack fires quickly and put them out when small – no firebreaks, no fire towers, no mobile vehicles with slip-on water tanks, no dedicated firefighters, and no bushfire brigades. They simply waited for a blow-up day and fires to leave the forests and descend on their properties and did their best to protect assets.

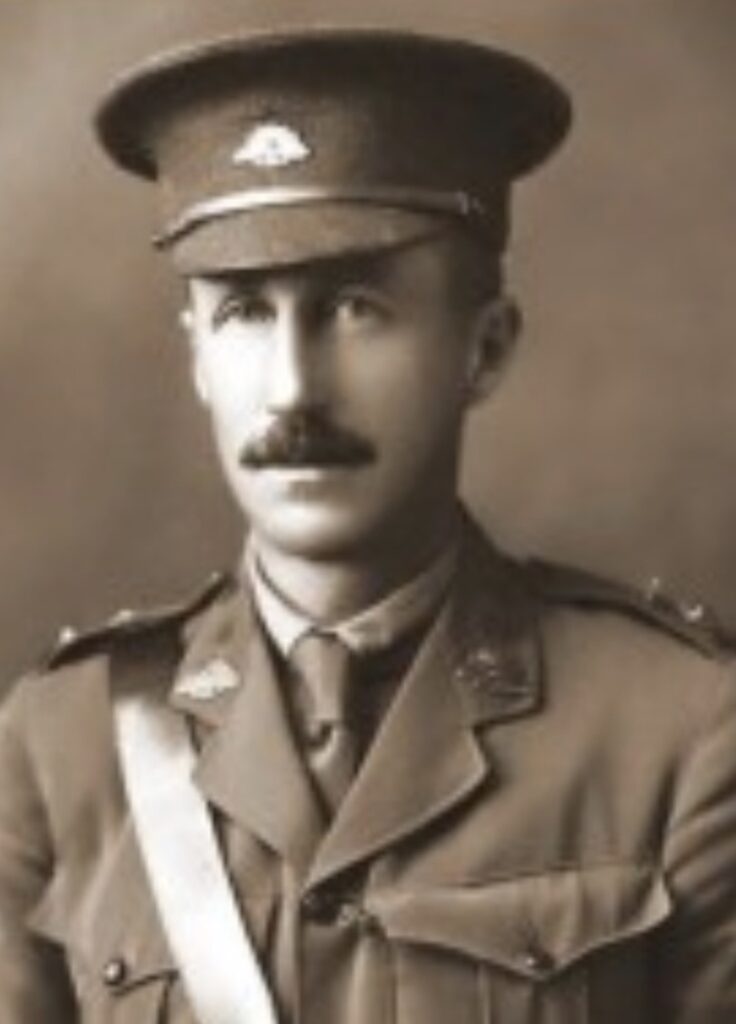

The Tasmanian Commissioner of Police at the time, Colonel John Ernest Cecil Lord, highlighted the weaknesses of the Bush Fires Act 1854. Part of the problem was the careless attitude to fires by landowners. They lit debris on scrubbed land or burnt heaps when it suited them, regardless of the weather conditions on the day or what was coming later. As a result, after fires entered the forest they were left uncontained with no organised attacks and exploded out of the forests onto settled lands during bad fire weather conditions. Even more so, during such a prolonged period of dry weather, the careless attitude became very acute around the state.

At that time, there also wasn’t a dedicated fire season where the lighting of fires was restricted. The Bush Fires Act 1854 prevented a landowner from “negligently lighting a fire or causing or occasioning a fire” to be lit during December, January, February or March on their land without taking precautions to prevent the fire from spreading onto adjoining land.

The problem for police in enforcing this requirement was that the affected landowners next door refused to give authority under the Act for the police to take action. Also, Colonel Lord pointed out that any court proceedings had to be taken “within too short a period”. Consequently, the bush fire legislation was revamped based on his advice, and a new, improved Bush Fires Act was introduced the following year.

Six weeks after the north-west fires, snow fell at Hampshire in the middle of autumn, and Surrey Hills had three inches. The 1934 fire season was finally well and truly over.

Summing up

From spring 1933 through the summer of 1934, north-west Tasmania experienced severe drought conditions that were almost unknown. A good rain event at the end of November brought good grass growth and other crops, but it was short-lived. Nevertheless, the combined effect of short-term feed and the devastating impact of caterpillars affected the farming community considerably. Added to this burden was the prolonged threat of wildfires.

There were a whole range of factors that, combined, allowed the 1934 fires to burn through most of the native forests in the north-west of the state – poor access, a lack of fuel management and an inability or a lack of priority to put out fires early.

Since European settlement, the 1934 fires were and still are the worst experienced in the north-west of Tasmania. When I worked in Tasmania and walked through areas of native forests on most of the freehold in the north-west, I became adept at predicting the volumes of standing timber. In some blocks, I was looking at a uniform stand of regrowth forest resulting from the 1934 fires that made my job that much easier.

It has been nearly 90 years since fires razed through the forests and farmlands of north-west Tasmania. Unfortunately, not much was recorded about the fires except daily newspaper reports where the fires threatened properties and assets. Time has a habit of erasing any memories.

North-west Tasmania is still lucky to support extensive areas of native forest. However, the high fuel loads in these forests will easily support fires on the scale experienced in 1934 if similar, prolonged dry conditions return.

A magnificent read as always Robert.

I wasn’t born till 1936 and this is the first I have heard of these fires. It must have been a fearsome time for the residents of some of these areas.

Keep up the stories, I enjoy them.

Great reading.

My father was farming at Oonah at that time and told me about the fires and how hot and dry it was.

I was born in 1946, so it would have been 1960s that I got the story on the fires. He told me about the Takone sawmill fire, how the horses in the stables were cut free with an axe and chased down the road in front of the fire. Items thrown into a dam at the mill were melted by the fire. Also fires would start up about 200 meters in front of the main fire because of the wind.

Thanks for sharing your knowledge of the fires Max. I didn’t know that level of detail for the Takone sawmill fire, other than it was a terrible experience.