“I am seeking [local and state government departments] to work together and take action instead of pointing the finger at someone else whilst your citizens experience a crisis that can be avoided or at the very least less impactful.” Submission to Select Committee Inquiry into 2022 NSW Floods.

Introduction

In February and March last year, New South Wales experienced widespread rainfall, which resulted in extensive flooding in some areas across the state. Major flooding, flash flooding and storm damage impacted the Northern Rivers, Mid-North Coast, Central Coast, Hawkesbury-Nepean Valley and Wollongong. Sadly, thirteen people lost their lives. It is one of the worst flooding disasters to hit the state.

The floods received extensive news coverage, and politicians, senior bureaucrats and “experts” were quick to label them unprecedented and something we could never anticipate. Wrong.

Simply put, preparing for flood events and responding to them was a massive failure in government policy.

The way the 2022 NSW flood emergency panned out is no different to the problems we have experienced with bushfire emergencies in the last 20 years. The failure to prepare, the wrong information, advice and modelling relied upon, and the poor responses have all contributed to deaths and properties lost or damaged.

Governments, their agencies and the bureaucrats never admit they are wrong. They never admit to their failings. Their speeches, reports and documents are creative acts of sophistry. Bureaucrats are conditioned to report only one way – positively. Everything they do is a winner. This is how the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) deftly phrased the shortcomings to falsely claim credit and deflect accountability:

“…the impacts of the floods were significantly reduced because of the preparedness of emergency management agencies and the level of cooperation, collaboration and coordination across the emergency management “ecosystem”. However, there remain opportunities to further reduce impacts on the community when similar circumstances arise in the future.

The New South Wales Government’s submission to the Select Committee Inquiry into the floods is replete with endless references to its “all-agencies approach”. They outlined the complex number of plans, policies, and procedures that confuse and deflect the reader into believing their centralised structures work in beautiful harmony like a well-oiled machine. Except they don’t. Bureaucrats write the document to please their political masters and keep their jobs. As a result, there is zero reflection on what went wrong and what may give poor light on the government and its policies. This has led to a shambolic response to significant fire disasters in the last 20 years, which is no different from flood disasters.

Never do the bureaucrats admit that perhaps their bureaucratic overload is part of the problem because what happened on the ground during the flood was different to the positive spin they portray. Unfortunately, accountability is non-existent when governments and bureaucrats are under the microscope.

This blog will highlight these failings by focussing on the flooding event at Lismore and downstream on the Richmond River.

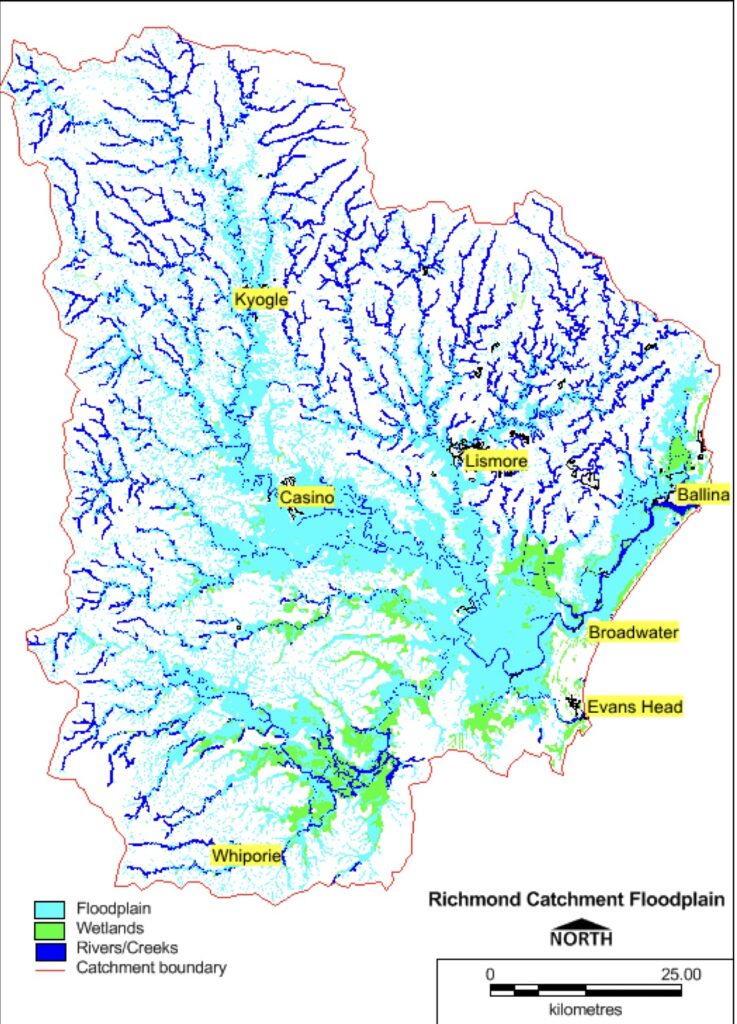

Flooding in the Richmond River catchment

The Northern Rivers district is one of the most flood-prone areas of the country outside of the tropics. During the late summer, autumn and early winter months, an extensive slow-moving high-pressure system can be positioned around 400South Latitude and provide moisture-laden south-east to easterly winds onto the north coast. Flood-producing heavy rainfall can occur if the high combines with a trough, low-pressure system, tropical cyclone or upper trough, and the blocking high keeps the associated rain-producing systems in the area longer.

For the large service town of Lismore, this is not good news. It is located at the junction of two major streams, Leycester Creek and Wilsons River, and it is often subject to significant flooding.

Extraordinary amounts of rain fell in the upper Wilsons River catchment during late February 2022. The towns of Tunchester and Rock Valley, upstream from Lismore, had 437 and 503 millimetres respectively of rain on Sunday, 27 February. This was much more than the 250 millimetres the BOM had predicted would fall. The situation was made worse because the catchment was already heavily saturated.

Consequently, in some areas, the floods were on a scale never experienced before. In addition, the enormous amounts of rain closed several local roads, isolated several communities, and precipitated numerous landslips and landslides in the steeper country.

At Lismore, the Wilson River reached 14.4 metres at 3 pm on 28 February 2022. This is significantly higher than the previous record of 12.11 metres and two metres higher than the predicted 1 in 100-year flood level of 12.38 metres. A month later, on 30 March, a second flood reached 11.4 metres. During both floods, the 10.6-metre-high flood levee was breached. It was built in 1999 to protect the Lismore town centre and the suburb of South Lismore from a 1-in-10-year flood event.

The February flood practically destroyed the small towns downstream from Lismore on the broad Richmond River floodplain, such as Woodburn, Bungawalbin and Coraki. Local residents were amazed at how quickly the floodwaters rose on the river and swamped them. An 86-year-old Woodburn resident, who experienced the 1954 and 1974 floods, said she never expected a flood would enter her home in her lifetime. Instead, she saw water rising as she looked at it and thought she was in a horror movie.

It usually takes a couple of days after Lismore floods for the water to get to Woodburn as it slows down and spreads after entering the broad, flat floodplain. But in February 1922, after flooding Lismore, the water in the Wilson River continued down the catchment joining the Richmond River at Coraki in record time, overwhelming that small town.

The floodwaters continued onto Bungawalbin, Woodburn and Broadwater. For Woodburn, the flood peak was 11 pm on Tuesday, 1 March, at 7.17 metres, smashing the previous record of 5.42 metres set in 1954.

Flood mitigation management in the good old days

After the disastrous 1954 flood event, a statutory flood mitigation authority was established for the Richmond River. It was called the Richmond River County Council, and its sole purpose was to create structures and develop processes and policies to mitigate the effects of flooding on the river. The authority was well-funded, well organised and very effective in its role. Some say too effective. As the structures and processes it created worked to protect the communities and allowed agriculture to flourish, its value was taken for granted, and a false sense of security developed. Flooding became part of the everyday ebb and flow of the residents’ lives. Each deluge added to the local folklore.

Eventually, funding was cut, staff was reduced, and maintenance ceased. The County Council was absorbed into a new entity called Rouse Water in 2016. It amalgamated the Richmond River, Far North Coast and Rouse County Councils as part of a rationalisation process.

Unfortunately, the decline in the County Council model over the years allowed other government departments to assert their relevance and formulate river policies, management plans and restrictive rules. As a result, seven government departments have jurisdiction over land, water and vegetation surrounding flood mitigation infrastructure.

There is no longer a whole of government approach to floods with individual fiefdoms ruled by personal ideologies rather than the greater good of the whole catchment. Common sense was the first major casualty in this bureaucratic mess – public service overreach and messy and confusing legislation became the norm.

What catchment residents are now burdened with are countless management plans and studies collecting dust on bookshelves and numerous procedures, permits and permissions preventing works near and on the water. In addition, no one flood mitigation authority exists to upgrade and effectively manage flood mitigation infrastructure. As one affected resident said:

“…people’s properties are flooding as more studies or Catchment Plans or Coastal Management Plans are done. Action must be taken now to address the drainage network before more weather events further impact properties and cause further trauma and financial impact to residents”.

Instead of scarce funds directed to proper plans for future flood mitigation, it is now a cash cow for universities and consultants that produce no meaningful result in flood mitigation. A classic example was the installation of expensive water quality monitoring stations by Southern Cross University in August 2021, which was hailed as a project where “universities can help solve real-world issues…for the Government Marine Estates Management Strategy”. Meanwhile, the rain gauges, so critical for predicting flood heights in advance during periods of heavy rainfall, remained old and faulty.

The result is clogged government-owned drain outlets to the river and crumbling infrastructure. The Newrybar Valley Canegrowers Union was previously responsible for drain maintenance, including mechanical cleaning of the drain network. However, since responsibility shifted to Rouse Water and Ballina Shire Council, mechanical clearing has not occurred in the past ten years. Consequently, flooding frequency has increased in some streets in Lennox Head. The Tuckmobil Canal is also blocked, and there is massive siltation and shallowing of the lower river and river mouth. And tragically, there are greater threats to life and communities.

Inadequate warnings

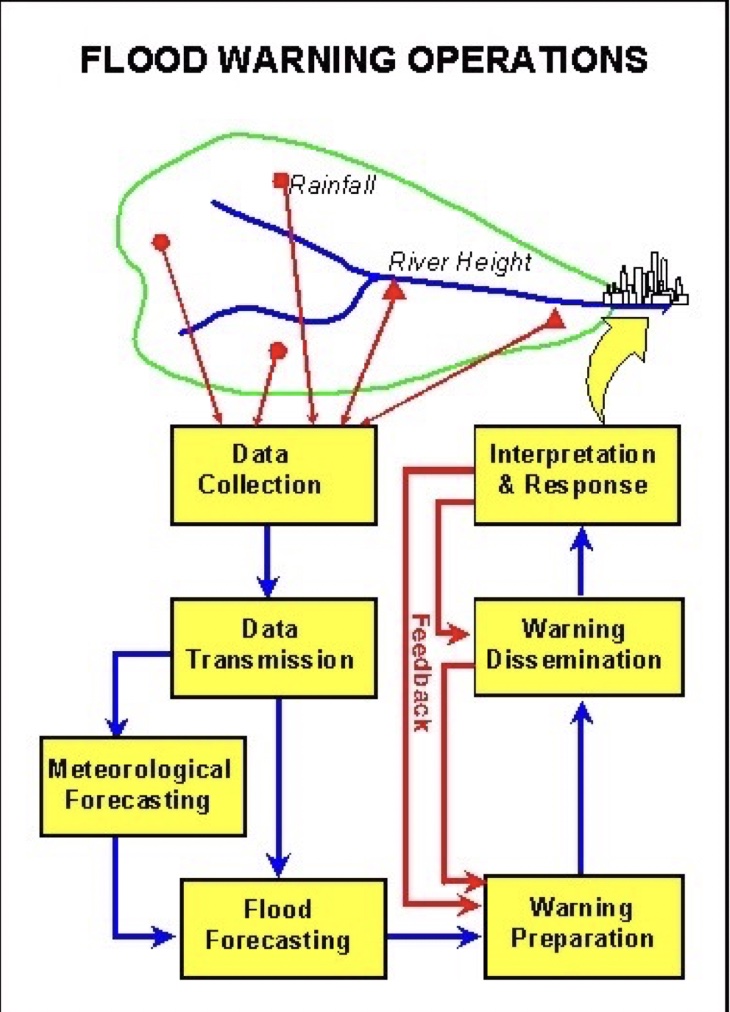

Major and moderate flooding events are no stranger to residents and farmers along the Wilson and Richmond Rivers. It is a part of living in the region. There have been 78 occurrences since 1887. They are aware of the risks and consequences, are well prepared and cope with these events if they get adequate warnings. From the time flood rains start falling on the northern border ranges, accurate information has been critical for the emergency management response and preparations for those settlements that are situated above the expansive floodplains, including Lismore. Major flooding can occur within 8-12 hours. Rural residents and farmers use that time to shift livestock and equipment to higher ground, and urban residents and businesses need as much time as possible to pack up and move assets.

In Lismore, the locals knew the pattern. They knew when water would break the bank in front of the police station. They knew when it would start to enter the various streets. They knew when the shop owners would begin to pack up and move their stock. They knew when to get their cars out of the city centre. And they knew when they would consider it unsafe to be anywhere near the square. It was local information that was supplied through a locally driven emergency response.

But things have changed, and dramatically for the worse. Gordon Bebb is a sugar cane farmer near Wardell on the Richmond River. He has lived and farmed on several sections of the Richmond and Wilson River catchments all of his 67 years. While the 2022 flood was the biggest on record using data that BOM relies on, he points out it is not the biggest on record using past rainfall recorded at the old Lismore Post Office and local knowledge.

Bebb highlights that up to about 2010, flood warning systems were very effective. River heights at the many gauges along the river catchments were measured manually by volunteers and collated locally at the New South Wales State Emergency Service (SES) centre in Lismore.

They predicted expected flooding times and heights, and a timetable for flooding was announced at hourly bulletins on the local radio stations.

The accuracy of these predictions was often within an inch because local people, with years and often generations of experience, managed the rain gauge data. So, for example, Lismore would get 6-10 hours’ notice before the expected peak, Coraki 24 hours and the lower river settlements 2-3 days’ notice.

However, the locally based emergency services are now replaced by a highly bureaucratic centralised system. With their large budget and salaried staff ensconced in Wollongong, SES is far removed from the needs of the local community. Critical local knowledge is no longer relied on nor sought. Instead, the river heights are read by automatic telemetric systems that are promoted as being more reliable.

The only local activity the residents get these days is a “community awareness and engagement” campaign which the New South Wales Government bureaucrats proudly boast won the National Emergency Media and Public Affairs award for Excellence Readiness and Resilience. The campaign’s achievement was to educate locals “there isn’t a flood boat to come to every house” and ensure they have a flood plan. It is a pity the campaign didn’t focus on the problems big governments have preparing for and responding to a disaster designed to fail. Then they would be deserving winners of the excellence award.

There is no doubt things were different in the lead up to the 2022 flood. Prior warnings and preparedness were virtually non-existent or inadequate.

The major problem was that up to 75 per cent of these “more reliable” telemetric gauges were not working before and during the unfolding flood. Plus, BOM’s official automatic weather station at Lismore Airport was broken down. This created massive problems forecasting river heights and flood levels, exacerbated by the lack of local knowledge input.

A serious and concerning example was the Terania Creek rain gauge. It stopped working on 3 February 2022. A surveyor from the area, Ken Chelsworth, has records from his personal rain gauge showing over 900 millimetres fell in 18 hours before it overtopped. As a result, Terania Creek rose very fast, changing course in several places, destroying bridges and roads, and flooding homes and the tavern at The Channon, before causing life-threatening destructive flooding in the Keerrong Valley. A failure to repair the gauge as soon as possible shows a complacent attitude to catchment monitoring and led to serious consequences for local residents caught in an extraordinary flash flooding event.

Numerous examples of problems with creek and river rain gauge management were expressed at the Inquiry. For starters, the gauges are managed by multiple organisations, and it is difficult to know who owns which ones. In terms of real-time catchment data, most are hidden from the public. One person highlighted that when the BOM website said Terania Creek was “steady”, a local resident had to ring SES to warn them the creek was rising fast and about to flood their home. The SES person could not understand why they were calling. BOM also continually displayed that creeks were “steady” when locals witnessed waters breaking banks and entering their paddocks.

Timely information was sought solely from the BOM, who only issued warnings every four hours. Under this new and “better” system, residents no longer got the accurate hourly forecasts and predictions they were used to, and which are critical. BOM issued over 23 flood warnings during the major flood event. However, the Inquiry into the floods heard that many warnings and associated evacuation orders were out of date by the time they were issued, risking safe evacuations.

For the residents below Lismore on the Richmond River, the first warnings came way too late on Sunday, 27 January. BOM stated on their website at 9:45 pm that the Wilson River at Lismore would peak the following morning with minor flooding, with an evacuation warning issued for 5:00 am the next morning for the Lismore CBD. After I spoke to a number of local residents and farmers, they said they based their decisions on the BOM reports. Some workers, such as hotel cleaners, decided to stay in Lismore. Most locals used to the flooding set about their normal preparation for the following day. For example, Toyota decided to leave an assessment whether to move vehicles until the next morning as they had built the premises way higher out of flood reach. So the Lismore residents and those further downstream went to bed feeling comfortable that everything would be alright that night. But it wasn’t.

The radar images showed the weather system sitting off the coast had stalled. It was dumping rain all over the northern river catchments. Only 15 minutes after BOM predicted a minor flooding, many locals sensed the situation was much worse, particularly for those who had no power and could not access the web. Locals upstream witnessed a disturbing amount of rain in the late afternoon. The upper catchments that flow into Lismore recorded a cloud burst of as much as 183 millimetres of rain in 35 minutes and the water began to rise noticeably in Lismore not long after. But because BOM and SES didn’t rely on local information and many rain gauges weren’t working, they didn’t pick up on this straight away.

That night, flood waters rose dramatically, and those who still had power watched the river rise on the BOM website in disbelief. It was a harrowing experience for people who found water coming through their floorboards as the flood continued to rise in the darkness. Some people found themselves stranded on their roofs as they frantically waited to be rescued, listening to others screaming for help through the night.

BOM and SES still had not said anything public and certainly gave no indications that the situation had shifted into a catastrophic situation. It wasn’t until early the next morning the official warnings changed to a major flood. At 9:51 pm, an evacuation order was issued for South Lismore, and another five minutes later, an evacuation order was for North Lismore. At 1:11 am, an evacuate order was updated for all of Lismore due to rapid river rises. BOM also issued a statement for “major flooding for the Middle Richmond River”, but no location or place is known locally as “Middle Richmond River”. This only sought to confuse locals.

The total reliance on ABC Radio to broadcast warning was exposed at approximately 9:30 am on 28 February when the local ABC North Coast radio station lost electrical power during the critical stage of regional rescue and could not broadcast until a back-up generator was sourced.

BOM’s predictions were at least five metres (yes, five metres) out. By the time BOM revised their river height predictions that night or early the next morning, which still ended up being some 2.5 metres below the actual height, it was way too late for residents and farmers to deal with animals or evacuate themselves safely. They were left in a precarious situation with limited available SES assistance.

The SES initially requested community boat assistance but later advised the community to keep their boats out of the water until they were registered with the SES by filling out forms and their boats checked by SES personnel. Risk averse bureaucrats chose to ignore the plight of flood victims rather than deal with the problem at hand.

Many locals were forced to take matters into their own hands and coordinate the rescue and recovery efforts using a flotilla of boats and jet skis, ignoring the SES headquarters edict not to enter the water. Thank God they did, as hundreds of lives were saved.

This shows how far removed from reality the situation decision makers in Wollongong were. It is also a clear demonstration that flood management’s structure and decision making need to be locally managed.

The very short notice for Lismore residents sadly meant some lives were lost, and others had harrowing experiences.

The ones caught out suffered terribly. People were left stranded on their roofs for a long time, with no access to 000 services to call for help and no access to information about what was happening around them. This is unacceptable. The ones that could call through, dialled a completely overwhelmed system. There were reports that one granddaughter in England read the plight of her grandparents on social media and tried to coordinate help for them by appealing to locals on that forum.

While staying in Kyogle, I heard firsthand from a couple about their experience. They had to be rescued from the roof of their house in South Lismore. Listening to them, it was evident it was a very traumatic experience. They trusted the warnings from the authorities, but it nearly cost them their lives. They said they couldn’t get any information about what was happening when things were going pear shaped.

Communities rely on telecommunications to keep them informed. Yet these services consistently fail. Nothing has changed despite the same problems during the 2019-20 bushfire emergency and subsequent recommendations to improve telecommunications networks and back-up power supply. Tax payers have subsidised investment in telecommunications infrastructure over many years, and customers have paid premium prices for access. They deserve better.

It is clear to the residents in the Richmond River catchment that when the accuracy of river height predictions is compromised, timetabling becomes a lottery, and the impacts are compounded on unsuspecting residents.

For local SES, the whole flood disaster was a shambles – slow BOM data acquisition and computer simulation capabilities created a time lapse between much-needed information from central command in Sydney to the local units and the flood-affected community. As a result, the BOM flood warnings were not synchronised with what was unfolding on the ground. Moreover, SES were acutely short on numbers, and the Inquiry heard this was mainly due to their mandatory covid vaccination requirement. So, it is no surprise a very high-magnitude disaster occurred.

Premier Dominic Perrottet offered a half-hearted apology to flood affected communities, some left without any help for five days. Local SES units were light on numbers because instead of sacking incompetence, the SES hierarchy were more interested in sacking the unvaccinated starting as far back as October 2021. They were also widely and rightly mocked on social media during the floods for insisting that volunteers wanting to help sandbag homes had to be vaccinated and RAT tested first. They clung to Covid health orders, turning volunteers away during a crisis, even though vaccine mandates were in the process of being dropped around Australia. While the public could go to most restaurants and retail outlets, catch public transport, and congregate elsewhere in the state without restrictive mandates, in the Richmond Valley they were not allowed to help their local community. Vaccine mandates for the SES were more important than saving lives.

Is climate change making floods worse?

As with every natural disaster that occurs these days, the floods were described as unprecedented and directly resulted from accelerated climate change caused by humans. The newly merged ex-Fairfax and Nine media entity laid it on in their Western Australian newspaper, declaring, “climate change is making floods in eastern Australia more extreme in meteorological terms”. Other mainstream media outlets also reported that climate change was the culprit.

Relying on climate change as the sole cause of natural disasters is a form of causal fallacy. An illogical assumption is used to claim that a specific factor caused a particular effect. It is so easy and convenient to blame every extreme weather event on a planetary climate system spinning out of control due to humans, enveloping us into a “climate emergency”.

The media and the government need to report a more reasoned analysis and stop scaremongering. We know that at least four factors caused the weather pattern over south-east Queensland and coastal New South Wales in late February 2022. Warmer than usual sea surface temperatures in the western equatorial Pacific allowed more moisture to build up in the atmosphere. Cool air in the upper levels destabilised the atmosphere, which allowed air that was lifted by converging winds in the low levels to remain buoyant and lead to clouds and rain. Third, a series of troughs near the coast created a conveyor belt of moist tropical air over the Coral Sea, creating an “atmospheric river” which moved slowly, drifted over land at times, and produced the heaviest rain. While the actual sequence of those events was relatively unique, those weather patterns have happened previously.

Similarly, while the amount of rain that fell in the upper Richmond River catchment in late February is undoubtedly extraordinary, massive amounts of rainfall have fallen on previous occasions.

The historical rainfall data shows that the February rains, while extraordinarily high and damaging, were not unprecedented. The wettest year on record at Lismore is 1893 with a total rainfall of 2,213 millimetres. The wettest day on record at Lismore is still 21 February 1954, when 334.3 millimetres fell.

So where is the media getting the idea that Lismore has never seen such rain before? Well, in its monthly summary for February 2022, BOM claimed a new 24-hour record for Lismore of 146.8 mm from the Lismore Airport even though they only began recording rainfall data at the airport in 2003.

That means BOM ignored the longer historical record from Centre Street Lismore which began recording rainfall data 127 years ago. This long-term data shows there’s no evidence that the number of days of extreme rainfall each year or the intensity of this rainfall has increased for the period 1885 to 2021 at Lismore.

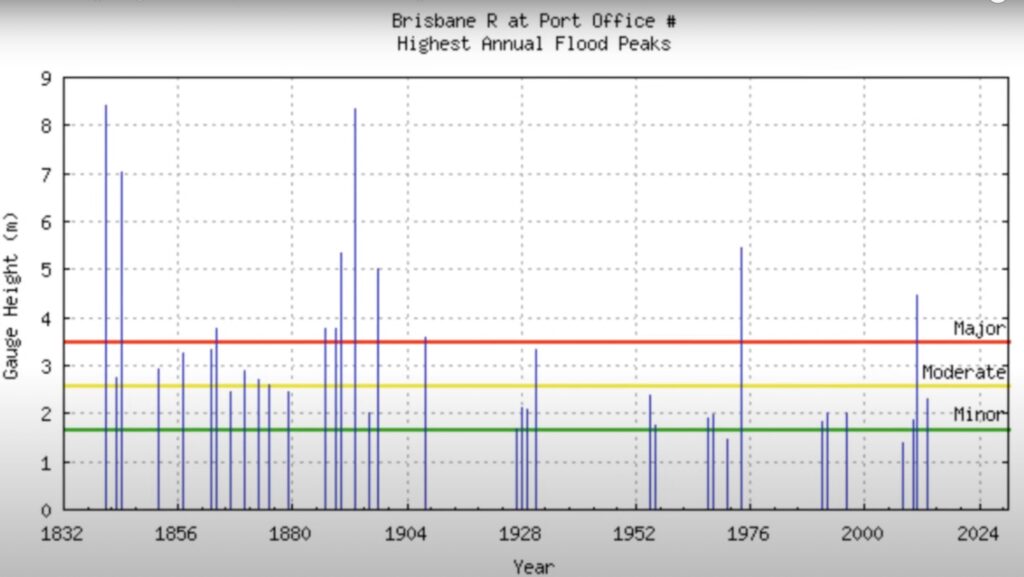

Brisbane, a capital city prone to significant flooding events, has received extraordinary amounts of rainfall in its catchment in the past. However, for records going back to 1900, the 1974 and 2011, and 2022 floods stand out. The 2011 flood was described as a 1 in 100-year flood event or an “inland tsunami”, yet the river’s peak was lower than in 1974.

However, looking beyond 1900 to the beginning of records shows massive flood events in the 1800s for Brisbane. The flood of 1893 was four metres higher than the 2011 flood, and the 1841 flood was even higher. There were nine major floods in under 80 years in the 1800s. The 2011 flood height has been breached six times in under 200 years.

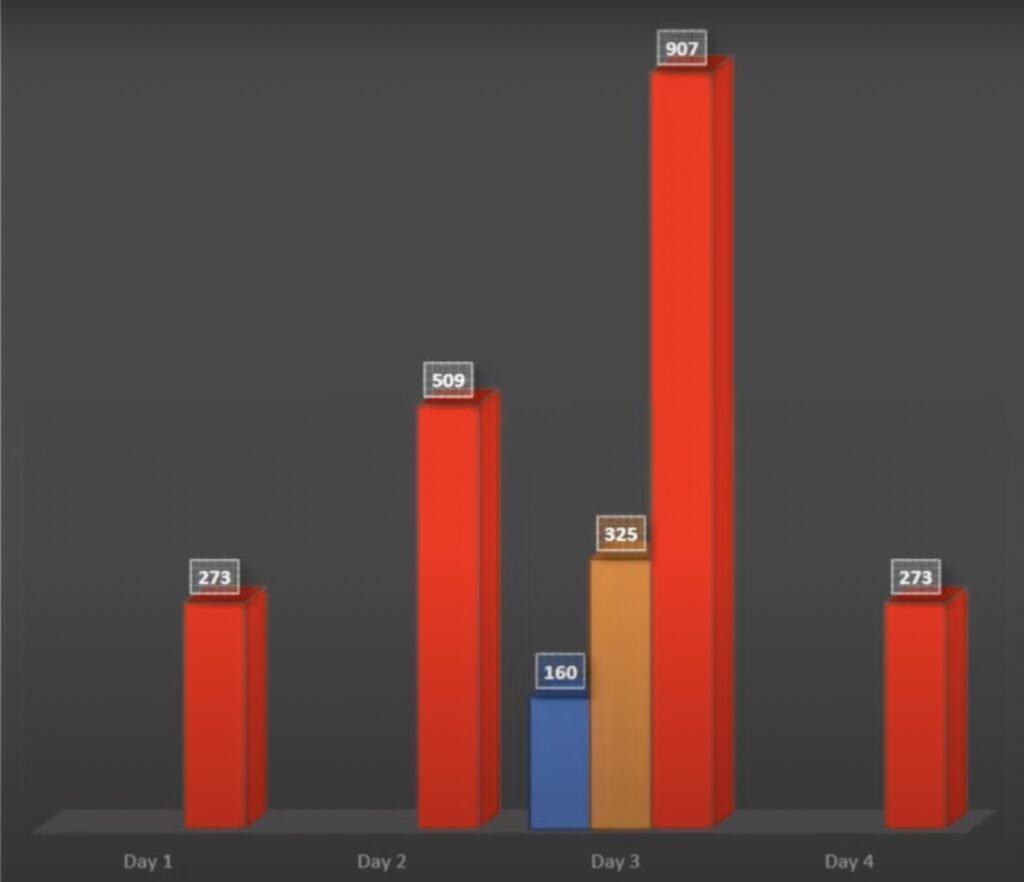

The variances in flood years in some instances can be explained by flood mitigation works in more recent times. But observing rainfall records shows that rainfall radically differed from the current floods. For example, in February 1893, in the Brisbane catchment, 900 millimetres fell in 24 hours. On the day before, 500 millimetres fell. And the day before that, over 200 millimetres fell. More rain fell in that week of 1893 than in every flood event from 1893 to now. Not only that, but it was also just one of three floods that year.

Comparing the rainfall from 1893 with the 2011 and 1974 rain events shows the magnitude of rain that fell in 1893 was massive. What is more frightening, more rain fell in the 1841 rain event than in 1893.

What happened in Brisbane isn’t isolated from the Northern Rivers or the North Coast. For instance, Dorrigo has a sub-tropical climate influence like Brisbane. Its maximum rainfall event was in 1954, when 809 millimetres fell in 24 hours.

A major criticism of flood modelling used to plan for floods today is that it ignores these historical records. Indigenous folklore is also overlooked. It then allows the politicians, bureaucrats and “experts” to use a “get out of jail free” card and claim, as Barnaby Joyce did, the 2022 floods were a 1-in-3,500-year event, unprecedented and impossible to plan for. This is code for removing any accountability the government and its agencies should have for the failings in preparing and responding to the disaster that unfolded.

However, for the public affected by the floods, attributing blame to the esoteric concept of “climate change” overlooks and ignores more plausible causes that enable problems to be addressed to alleviate future flooding effects.

The major question that needs to be answered is why an effective and successful management system of flood mitigation in the Richmond River catchment, which worked effectively in the past, was replaced with one that is clearly ineffective, cumbersome and onerously bureaucratic.

A new significant problem

According to many locals, there was something not quite right about the behaviour of the floodwaters in 2022 downstream of Lismore on the broad floodplains. While it is recognised that every flood behaves differently with varying rates of rise, peaks and rates of decline, they generally follow similar patterns in terms of pathways and spread.

In February 2022, something was holding back the water that had fallen in Woodburn, Coraki and Bungawalbin catchment. Residents are now questioning why the flood took so long to recede and whether were other reasons for trapping the water.

During the 1890 and 1954 floods, the low-lying country between Kilgin and Salty Lagoon near Evans Head on the coast was covered in water. This indicates that the floodwaters could spread and disperse over more extensive areas towards the sea, thus reducing the back-up of water and the potential for higher flood levels. However, even though the 2022 flood was recorded as two metres higher than 1954 further upstream at Lismore, the floodwaters got nowhere near Salty Lagoon. 82-year-old farmer Ray Boland, who has lived at Kilgin all his life, believes the passage of the 2022 flood waters was blocked or restricted in its ability to disperse towards the sea.

Fingers are being pointed at the newly built Pacific Highway, which they believe has created a levy bank or a dam wall.

The 657-kilometre dual carriageway between Newcastle and the Queensland border was finished in late 2020 after 24 years and cost $15 billion. On day seven of the flood disaster, it was evident from the air that the water was banked up on the western side of the highway and couldn’t move. A dam had effectively been created.

Thomas Searles is a Lismore-based surveyor. He worked on the Pacific Highway upgrade project as cadastral and geodetic integrity manager on either side of the corridor. In this video, he shows the highway across the floodplain at the lower end of the Richmond River, which has a series of box culverts about 1,000 x 1,000 millimetres. But as Thomas points out, all the water that flowed through those culverts had to discharge through just four 450mm pipes on the eastern side of the highway.

To prove how inadequate those pipes were in taking all the water, they were thoroughly washed away in February and were re-installed with a concrete apron soon after, as shown in the video. But the problem remains because all the water must be discharged via a small drain or creek.

Many buildings and properties that had not previously been flooded experienced flooding for the first time, including several 130-year-old-homes. Woodburn resident Vanessa Allport saw her 80-year-old single-storey house at Woodburn get inundated by two metres of floodwater. Her home had never previously flooded in the past 100 years.

During heavy rain and excess water from the catchment, the water simply cannot get away, forming a dam west of the highway.

This is what happened in February 2022. The aerial photo (above) shows the impacts as Broadwater, Woodburn and Coraki were hit not only by water coming down from Lismore but the water that couldn’t drain properly away.

For this reason, local farmers expressed concerns about the design of the highway across the floodplain before the highway was built. But, yet again, locals were ignored.

Transport for New South Wales was the government agency responsible for the highway upgrade. They carried out several flood studies to ensure the highway’s impact was kept to a minimum level. They claim the highway was designed, through extensive flood modelling, not to impact flood levels by more than 50 millimetres or extend flood duration by more than five per cent. But talk is cheap if the modelling is not correct.

The new Pacific Highway crosses the floodplain north of Woodburn on the eastern side of the Richmond River and east of Woodburn and Broadwater. During the March 2021 flood event, local landholders whose boundary ran along the new highway were impacted by flood waters, either held back or sent in a new direction. These first-time impacts of the new highway were not recorded in any flood plans.

A community liaison group was established during the construction phase, set up by the then Roads and Traffic Authority to plan the route for the new highway. Residents of Woodburn claim they raised concerns about the route over a low-lying floodplain and not on piers. They agitated for the highway to be moved to higher ground. When they also questioned the adequacy of the drainage and culverts, they claimed they were told: “all the relevant modelling had been done”.

The Terms of Reference for the Inquiry were so narrow that, conveniently for the government and Transport for New South Wales, the issue of the new highway contributing to the flooding event was not even considered. Yet again, government and bureaucrats avoiding accountability.

Wrap-up

In the last decade, millions of thoughtful, experienced, evidence-based words have been written in submissions to various national and state inquiries. Still, they largely appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

The current lack of preparedness for an increase in the frequency and severity of catastrophic natural events reflects a profound weakness and failure in national risk management systems. The causes for these deficiencies are complex but include inefficient bureaucratic overreach and the utterly unrealistic reliance on the altruism and goodwill of a volunteer workforce that is completely inadequate to respond effectively to large-scale or protracted catastrophic events.

And because emergency service volunteering embodies ideals like selfless service, courage and mateship, the function is considered beyond objective and critical analysis of actual capability and accountability.

One thing is for sure: this flood event and recent bushfire emergencies have highlighted the need to review the emergency response model in New South Wales and Australia. The clunky, complex, and out-of-touch centralised system needs to stop.

Local knowledge and experience had been dismissed and replaced with project management that identifies and caters for vocal individuals but ignores those with lifelong learning and experience.

It is high time the bloated emergency service bureaucracy is trimmed drastically and remodelled to work for the citizens’ best interests, not the public servants. Perhaps they could start by displaying a greater sense of urgency, or in public service speak, “agility”, to do their job. They must be better prepared based on what happened last time, not their esoteric “what if” scenarios through their wasteful plans or naval gazing about climate change.

Using a multiple emergency response model has led to unsustainable funding requirements to support it. The Emergency Services Levy (ESL) charged to ratepayers through the local council needs to be reassessed. As with all things bureaucratic, there is zero accountability on how the ESL funds are spent. Millions are thrown at the emergency services after each disaster, and the outcomes never improve. Go-to academic “experts” that provide advice are never held accountable when their advice doesn’t work.

Residents of Lismore first sensed changes for the worse with the poor preparation and response to the 2017 flood. But by February 2022, the new bureaucratic nightmare was embedded, and there was a sense of despair and desolation for the first time. Lismore has now changed forever.

But can it survive? It can, but the army of bureaucrats, well-paid consultants and academic “experts” need to get out of the way. There needs to be the reinstatement of a single authority with sole powers to plan and conduct long-term strategic works, as well as ongoing maintenance as a priority over other esoteric results. Legislation and regulations need to be simplified.

Lismore needs to reimagine itself away from its historical roots on the river. If Darwin could be rebuilt after Cyclone Tracy in three years under greatly improved building standards to ensure it survives another cyclone, then Lismore could rebuild itself through meaningful steps to minimise flood impacts.

They could start by excavating some of the bends in the Wilsons River and removing old railway embankments that would speed up water displacement. They could also restore flood mitigation infrastructure, remove siltation of the lower river, clean out government-owned drains outlets, replace the fixed weir across the Tuckmobil Canal and install a sand bypass on the south wall at Ballina. These works would not have prevented the 2022 floods but they would have lessened the impact.

Finally, there needs to be a complete review of the siting of the new highway across a major floodplain and the adequacy of the current drainage works. It is important for local community confidence that their concerns are investigated and there is an appropriate review of the flood modelling and structural design for the Pacific Highway.

An insightful, frank analysis of this tragedy and the shameful negative contribution from our know-all bureaucrats who are obsessed with their own importance.

They in turn provide cover for elected politicians who hide behind the new religion of climate change!

Well done Robert, and I hope some of the main culprits read this and reflect on their shortcomings rather than their usual response of trying to shoot the messenger.

Tragically, and sadly, ordinary decent citizens lose their lives and livelihoods whilst the bureaucrats grow fat on the mirage of all-knowing expertise and preparedness.