My previous war story blog provided details of the bombing of Darwin and the subsequent battles against the Japanese in the Coral Sea and Papua New Guinea.

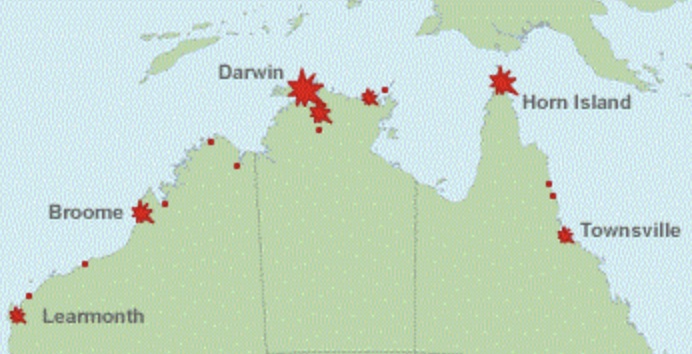

After the bombing of Darwin on 19 February 1942, the Japanese carried out further air-borne attacks across northern Australia. In total, between March 1942 and November 1943, the Japanese flew 64 bombing/strafing raids on Darwin alone and 33 bombing/strafing raids on other targets in Northern Australia. For a complete list of enemy raids on Australia in 1942-43 see here and here.

Many Australians today does not realise how close the war came during WWII and how real the threat of invasion was. To understand this more, I would like to provide some background to the overall defence strategy Australia adopted immediately prior to the Pacific War.

Australia’s lack of preparedness to defend its shores and strategic outposts in South-East Asia

From September 1939 to November 1940, Australia concentrated its war efforts in Europe to assist Great Britain’s fight against the Germans and Italians. Between November 1940 and May 1941, there was increasing concern at the weakness of the Singapore naval strategy for the overall defence of South East Asia and Australia from Japanese aggression. At the beginning of 1941, most Australian naval units were in the Mediterranean; the newly raised 2nd Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was in the Middle East and there was little Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) modernisation. This meant that Australia’s available forces to meet a possible war against the Japanese was limited. In short, Australia held staggering deficiencies in preparing to wage modern warfare due to a lack of trained troops, staff officers and a chronic shortage of military material. For example, munitions of all kinds, but especially Bren guns and other automatic weapons, had to be allocated on a priority basis direct from the factories.

The British Royal Navy (RN) operated the Singapore naval base and successive Australian governments held on to the belief that Singapore was a guarantor of the nation’s security in the Pacific. This led to a concentration of defence spending biased towards the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) at the expense of the Army and RAAF. Even so, the RAN was small and designed to complement the much larger RN. The outbreak of the Pacific War exacerbated the deficiencies in Australia’s defence position.

From June until December 1941, Australia saw a need to move its war effort towards securing the south-west Pacific. A commitment to hold defensive bases on Ambon and Timor in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) was given priority. It was seen that security in the Dutch East Indies supported that of Singapore and Australia itself. Land forces were sent to the Dutch bases on Ambon and Koepang airfield on Timor. Ambon was strategically important because of its deep-water harbour, but it was very difficult to defend.

The two islands would also act as forward operating bases from which RAAF units stationed at Darwin would fly missions. Army garrisons were to man and protect the airfields. However, this strategy was flawed because Australia had no credible air power. All they had were 175 aircraft made up of Wirraway light bombers, Hudson medium bombers, Catalinas and Empire flying boats.

Also, the British were still seeking US support for the defence of the Dutch East Indies, and they feared that the movement of Australian forces to Ambom and Timor might lead to the Dutch requesting a guarantee of support from the British in the Pacific in the event of a Japanese attack. Therefore, the mobilisation of Australian troops was withheld until hostilities with Japan started. This would give no time for the Australian units to establish an effective defence position. In the end, after intense lobbying by Prime Minister John Curtin and opposition leader Arthur Fadden, 100 advanced troops were sent to the islands on 27 November, just ten days before the outbreak of the Pacific War. Advanced parties of RAAF ground and operations staff arrived on 3 December.

Between December 1941 and February 1942, Australia’s available pool of AIF troops in the south-west Pacific area was only 34,000. There were 17,000 in Malaya, 2,400 assigned to Ambon and Timor and 14,000 posted to the Northern Territory.

The lack of pre-war preparation and troops and equipment made the defence of Ambon and Timor impossible. In the dramatic weeks between the bombing of Pearl Harbour on 7 December 1941 and the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942, saw the Australian command completely overwhelmed by the continuous Japanese military successes. A new and hastily formed Allied command centre was set up in the wake of Pearl Harbour at Batavia in January 1942 to fight the Japanese. It lasted only six weeks and was simply an exercise in crisis management. Japan’s skilful strategy of quickly seizing advanced island positions which formed an interior network of operational bases, allowed swift transfer of forces from point to point that was very effective.

The Allied defensive weakness was a lack of air power and as the Japanese advanced southwards, Ambon and Timor required rapid air-reinforcement. The Americans deployed nine USAAF air groups made up of a range of bombers in early January 1942. But it was a futile exercise because there was no proper engineering infrastructure, fuel resources and camouflaged pens to support this aerial contingent. Inexperienced pilots, some with only 15 hours training, were sent to fight in the defence of the Dutch East Indies.

By mid-January, the Malay barrier crumbled to the Japanese, they then cut off the Philippines from the Dutch East Indies, and seized air bases within range of Java, including Timor. Without Timor, and in particular Koepang airfield, the movement of short-range aircraft reinforcements between Australia and Java was impossible. On 31 January Ambon fell to the Japanese and the rest of the island fell on 3 February 1942 when Lieutenant Colonel Scott surrendered.

At Laha airfield, Japanese troops committed an atrocity by beheading or bayoneting to death 309 prisoners. Among them was Scott and several RAAF personnel who couldn’t evacuate before the Japanese attack.

When Ambon was liberated in September 1945, 74 per cent of the prisoners were found to have died, one of the worst death rates of allied troops in Japanese captivity. Only 302 Australian personnel, out of 1,159 survived the Japanese attack and subsequent imprisonment.

The fall of Ambon and Timor reinforced the possibility of an invasion of Australia. The Koepang airfield was within easy striking range of Darwin and the surrounding area.

It is this background that helps understand the ease with which the Japanese carried out its air raids over northern Australia.

Northern Territory bombings

The attacks by the Japanese on Darwin and surrounding areas continued after 19 February 1942. On the 16 March, two servicemen were killed and nine injured after 14 bombers attacked the RAAF airfield and anti-aircraft gun station at Bagot. A plane carrying General Douglas MacArthur tried to land at Darwin on 17 March but diverted to the Batchelor airfield about 50 miles away after reports of Japanese air attacks. However, there are no official records of any Darwin bombings on that date.

On the early afternoon of 22 March 1942 nine Mitsubishi G4M1 “Betty” bombers from the Japanese Navy bombed Katherine. One Aboriginal man named Dodger Kodjalwal was killed while hiding behind a rock, and at least two other people were killed in the air raid. About 90 high explosive bombs popularly known as “Daisy Cutters” were dropped on Katherine that day and it was the furthest inland attack during the war. The attack was primarily aimed at grounded aircraft but there were none at Katherine at the time. It is believed Katherine was targeted due to the large numbers of military personnel stationed in the town during the war. Luckily little damage was inflicted on the town during this raid.

After the war, local people and new arrivals built on the military framework and infrastructure which was left behind to create a much larger town than Katherine may have been if it had been left out of the war.

In late March, after the Allied fighters were unable to intercept several of the recent Darwin bombing raids, the Japanese decided not to send escort fighters. Unknown to the Japanese, however, a new system was adopted by the 9th Pursuit Squadron. They flew two teams of four Kittyhawks in the air at all times, with four on the ground in reserve.

The Kittyhawks successfully attacked Japanese bombers on a raid on the 28 March. While the Japanese managed to drop 83 bombs, two of their bombers were destroyed. The Japanese never flew another unescorted bombing mission to Darwin again.

A month later on 27 April, about 50 Japanese Zeros escorted bombers from Keopang headed towards Darwin. About 50 Kittyhawks from the USAAF were deployed and a fierce battle occurred. Four Australian serviceman on the ground were killed and three injured. Another raid on 13 June saw 19,980 kilograms of bombs dropped on the Darwin airfield damaging runways, fuel drums and the water pipeline.

The Darwin bombings continued to 12 November 1943.

Western Australia bombings

There were many ships along the Kimberley coast during the war and this made the Western Australian coastline a front-line from the Japanese air force during the war.

The second most deadly air raid in Australia occurred at Broome two weeks after Darwin, where the Japanese killed somewhere between 70 and 100 people. In Roebuck Bay’s treacherous and murky waters lie WWII the wrecks of 15 flying boats (a flying boat is a fixed-wing sea plane with a hull). The flying boats were sitting in the bay after stopping in Broome to refuel. It is one of the deadliest and least known attacks on Australia.

Although Broome was a small pearling port, it was also a refuelling point for aircraft. Also, after the bombing of Darwin, Broome became part of an aerial escape route for the evacuation of thousand Dutch and Allied airlifted off the Dutch colonial outpost of Java. The evacuation flights continued after the Japanese invasion of Java on 1 March 1942. Flying boats that arrived on 2 March were ordered to stay overnight at Broome to give the flight crews a rest. A lack of accommodation options in Broome for the passengers meant they stayed on board the flying boats. It wasn’t pleasant in the tropical humidity inside the cramped, hot and stifling cabins. That night, there were many flying boats assembled at Broome’s Roebuck Bay. The huge tide variations during March delayed flights as some flying boats were left stranded in the sand at low tide unable to be refuelled despite wanting to fly further south to Perth or overland to Sydney. On the morning of 3 March 1942, there were 15 flying boats in Roebuck Bay with Dutch refugees aboard awaiting high tide and refuelling.

Despite its unreliable communications, Broome became one of the most vital Allied operational centres in the Pacific War. The Americans thought it was far enough away from any Japanese interest. However, Broome did attract attention from the Japanese.

At 7:05 am on 3 March 1942, nine Japanese Zero fighters and a reconnaissance plane left Koepang in Timor in a covert operation with instructions to attack military aircraft known to be on the Broome airfield. As author Juliet Wills describes, “the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane was a masterpiece of aviation. Its long-range capabilities and manoeuvrability brought astounding victories to the Japanese in the early days of the Pacific war and made it a legend in its own time. With it, the Japanese had decimated the Allied forces…”

The Japanese pilots were not expecting to find 15 flying boats on Roebuck Bay. These included eight PBY Catalina flying boats operated by the RAAF, Royal Air Force (RAF), and US Navy, two Short Empires belonging to the RAAF and Qantas, and five Dornier Do24s operated by the Royal Netherlands Navy Air Service. It was a walkover for the Japanese. In the space of half an hour, the arrow flight of Zeros ensured no useable aircraft remained in Broome with a total of 23 aircraft lost. All the flying boats were burned and sunk at their moorings. Eight aircraft, including two Liberators and two Flying Fortresses were destroyed on the airstrip.

When the Japanese attacked Broome, they swept in, attacked the legitimate military targets of opportunity on the water not knowing they were full of the Dutch refugee civilians who had fled Java. It is not known how many refugees were on board the flying boats, but it was believed many were women and children. After the raid, about thirty bodies were retrieved from the bay and buried in a cemetery near Town Beach. The true death toll may well be higher as many others were never found. In 1950, the bodies were exhumed and moved to the Karrakatta war cemetery in Perth or repatriated to Indonesia.

A wireless operator and gunner in the RAAF whose flying boat was in Roebuck Bay was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and a British Empire Medal for his actions during the air raid. His aircraft was attacked and had its starboard wing chopped, sinking it. Corporal Andrew Ireland managed to get the rubber dinghy out, inflated it and picked up his crew and rescued four Dutchmen and a wounded Dutch woman who were in the water. As the flying boats were anchored nearly two kilometres offshore and a strong ebb tide was running, most of those lives might have been lost, but for Ireland’s courage. Other service personnel who watched the raid helplessly from the shore also heroically assisted in the rescue of civilians in Roebuck Bay.

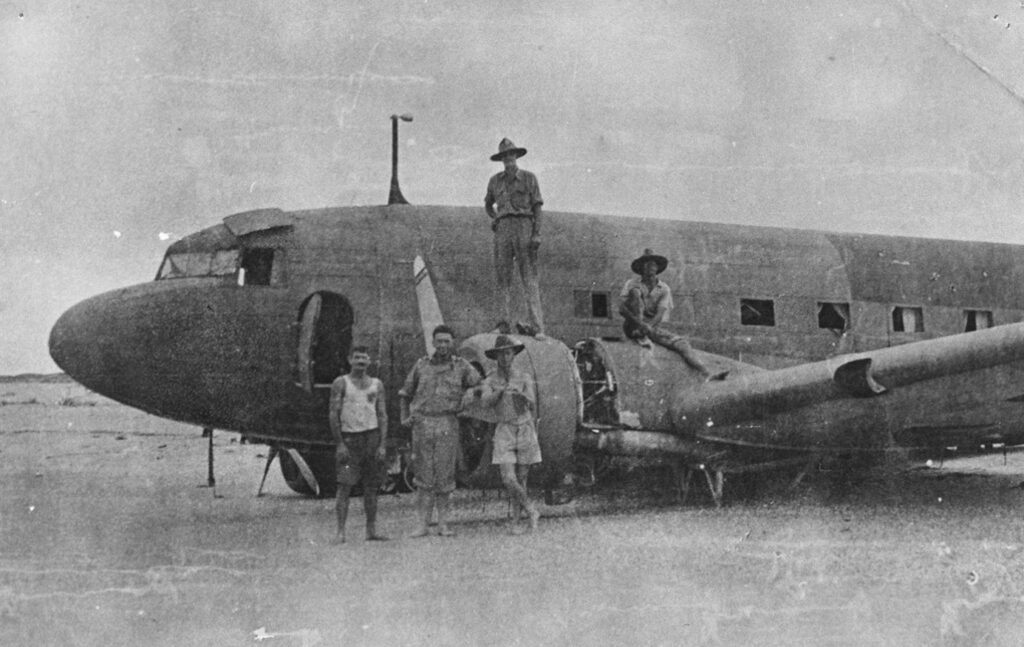

On their triumphant return to Timor, the Japanese came across a Dutch DC3 Dakota which was carrying 12 people, including Dutch refugees, heading towards Broome. They shot down the Dutch plane which made a forced landing on a remote beach 100 kilometres north of Broome. Four people died and the remainder were left stranded for five days with no food and little water. Aboriginal man Jo Bernard alerted the Beagle Bay Mission who rescued the survivors.

The downed plane was carrying a sealed secret package of diamonds that had come from Amsterdam for safekeeping in Australia during the Nazi invasion. The package was lost during the landing but was found by a local man, Jack Palmer on board the aircraft much later. He handed in a salt shaker filled with diamonds to the Army Commander in Broome. Because the container held many fewer diamonds than the package, an investigation was launched. Palmer was charged with stealing, but the case was dismissed and many of the missing diamonds were never retrieved. “Diamond Jack”, as he became known, went on to live a comfortable life in Broome.

Over the years the wrecks of the flying boats have become visible at very low tides. Amateur historians are documenting the wreckages. Maritime Archaeological Association making up a database of wrecks around the state. When the planes were attacked, they all caught fire and burnt to the waterline so there is no full structure sitting on the bottom of the Bay. A 3-D model of the Catalina wreckage has been produced to generate more interest in the attacks – bringing history to the surface for the wider public to learn about what happened in 1942.

Wyndham was attacked from a low-level on the same day as Broome. Three runs were made over the target with no casualties. The targets were the meatworks and airfield. A De Havilland Dragon was attacked while landing at Wyndham. The plane caught fire and limped to the end of the runway where the crew and passengers abandoned the plane and it burnt itself out. Nine “Betty” bombers then bombed the airfield leaving several large mud holes on the runway.

Derby was bombed on 20 March. Three runs were made over the target, but there was no damage and no casualties. Seven Japanese bombers also flew over Broome releasing about forty bombs. They targeted runways, petrol dumps and other buildings at the airport but most of the bombs missed their targets. One person was killed during the raid, a Malay named Abdul Hame Bin Juden.

On 23 March, Wyndham was bombed again as well as on 21 August.

In late 1942, the US Navy requested an airfield to be built near a future submarine base at Exmouth to service their submarines based at Fremantle. Until it was constructed, RAAF moved to nearby Onslow in February 1943 and then to Exmouth the next month. The Submarine Tender, USS Pelius, spent time in the Exmouth Gulf tending submarines that used the Gulf as a temporary base.

Late on 20 May 1943, two Japanese aircraft were detected by radar in the Exmouth Gulf area. At that time, the Australians were busy building the submarine base. Two RAAF Boomerangs were sent up to intercept them but failed to locate the planes. The Japanese dropped one bomb harmlessly into the Gulf. The next night, two Japanese aircraft were detected on radar inspecting the Gulf under a moonlit night, heading directly towards Onslow from the north. After flying along the eastern shore of the North-West Cape, they dropped nine bombs about 250 metres from shore. The camp at the airfield was only three kilometres away and was probably the intended target.

After those raids, combined with persistent north-westerly winds which produced a heavy swell in the Gulf, the US Navy decided to abandon plans for a Submarine base in the area and instead moved down to Fremantle. The RAAF maintained their two airfields after the US Navy left.

On 16 September 1943 more than one Japanese aircraft flew over Exmouth Gulf and dropped 16 bombs four miles south-west of Onslow without any damage or casualties.

Queensland

There were nine raids on Horn Island. After the bombing of Darwin, the airstrip at Horn Island, until 1944, was the nearest operational airbase to the Japanese forces in New Guinea. It was used by heavy bombers as the take-off points for attacks and to refuel on their return. The first bombing raid was on 14 March 1942 when eight Mitsubishi G4M1 heavy bombers engaged with US Kittyhawks above the Torres Strait. Further raids occurred on 18 March, and 30 April. On the latter raid eight “Nell” heavy bombers dropped about 40 bombs on the airstrip. Three Zeros that accompanied the bombers later strafed the runway destroying one Wirraway A20-472 and damaging another Wirraway. One soldier was killed. On the 11 May, four zero fighters strafed the runway hitting two already damaged Wirraways and one refuelling unit. Nine heavy bombers dropped 45 bombs near the dispersal bays. Another raid on 7 July inflicted minor damage.

Thursday Island was bombed on the 15 March and again on 20 March.

By the end of 1942, there were 5,000 troops on Horn Island and a further 2,000 on nearby Thursday Island. Altogether 190 Australian and allied personnel were killed in Torres Strait and 124 wounded.

The Japanese carried out three raids on Townsville between 25 and 29 July 1942. The raids were undertaken by two Emily flying boats which dropped 15 bombs near Townsville wharves where three vessels were berthed – SS Bantam, SS Burweh and the HMAS Swan. The second raid dropped eight bombs near the Garbutt airfield.

Summary

While the Australian mainland was not invaded, it was attacked on numerous occasions by air forces. By late 1942 the Curtin Government encouraged the belief that the Japanese planned to invade Australia as a means of encouraging all Australians, even those in the cities in the south, to embrace civil defence. Many experts today, however, believe that the Japanese plan was to wipe out as much of Australia’s and the Allied Force’s air and sea defences to gain control of the resource rich countries of South-East Asia and establish strong defences.

What I find unconscionable was the government playing down the threat by reporting much lower death rates and imposing strict censorship on the details of the attacks, in the belief the public would panic if they knew the truth.

That policy may have been appropriate during war time to quell any anxiety by the public, but when I was a young diligent school student learning about WWI and WWII in the 1970s, I would have appreciated if the school curriculum included a more truthful and open assessment of the threat of war on Australia’s doorstep instead of just a focus on the brilliant deeds of our servicemen overseas.

I would then not have been so surprised at the stories I came across when travelling through northern Australia.

If you would like to find out more about the Broome bombing, the Dutch refugees, Diamond Jack Palmer and the diamonds, I recommend the book by Juliet Wills called The Diamond Dakota Mystery – the amazing story behind one of Australia’s “most gripping mysteries”.

Very interesting Robert.

We were told very little about these attacks during the war. I believe the Japs came further south than Exmouth.

No mention of the 40 plane attack on Kalumburu, September 1942 – then known as Drysdale airbase. a secret airbase.

Track it down on ABC Radio National ‘Hindsight’ documentary from 1997 “They told us war is coming the story of the Kalumburu bombing”. Four raids on Broome in total.