During our travels to the Top End and following on from my earlier blog, ‘Some War Stories’, I have learned more about northern Australia’s involvement during WWII, particularly the bombing of Darwin in February 1942. Growing up in Sydney, I learnt about the Japanese submarine raids in the harbour. Still, I never heard anything about the broader invasion threats to Australia during the war. I find it amazing that a whole generation of Australian kids grew up with no knowledge of the war-time events on Australia’s doorstep in 1942 and 1943.

WWII started in September 1939 and was fought mainly in Europe and North Africa. By the 1940s, however, Japan was a powerful industrial, military nation. They had invaded Korea in 1905, gained the former German colonies in the Pacific after siding with the Allies during WWI, invaded Manchuria in 1931, China in 1937 and had a military influence as far south as French Indo-China (Vietnam). Japan had aspirations to be Asia’s most powerful nation. On 27 September 1940, Japan signed a pact with Germany and Italy to create a ‘Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere’ to eliminate colonialism and establish an Asian Federation under Japan’s leadership.

Although the USA was a neutral country, it strongly objected to Japan’s planned expansion into Asia. It imposed economic restrictions to stop the supply of much needed raw materials and oil. The USA also threatened military action in response. On 7 December 1941, Japan began a series of surprise attacks throughout the Pacific. The first was in Malaya and Thailand. They then followed just a few hours later by bombing and destroying Pearl Harbour in Hawaii, where the US Pacific fleet was based. The attack precipitated the other conflict of WWII – the Asia-Pacific War. Japan and the USA entered the war, and Australia, the rest of the British Empire and its Allies joined in the battle against Japan. Japan continued its attacks on the Philippines the next day, followed by Hong Kong, Guam and Burma.

By March 1942, any defence of the Philippines islands against the Japanese became impossible. American and Philippine troops were forced to retreat to the Bataan Peninsula and the island fortress of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay as the last stand. Re-supplying those troops was difficult as supply ships were attacked and sunk. Only three made it to the fortress. Due to a lack of food and water, the troops on Bataan Peninsular were forced to surrender. The remaining 11,500 men on Corregidor surrendered a month later. Some recognise this defeat as the worst suffered in American military history. Over 30,000 troops were captured or died at the hands of the Japanese.

Darwin was a sleepy town in the tropical Australian sun before WWII. It had neat attic cottages of the Greeks under the poinciana trees. There was the walled campong settlement of the Malays and Islanders. The laced bamboo huts on stilts built by Manila men. Tiny bird-cage houses and shops of the village in ‘Tokyo’ with their matting beds, small shrines and miniature gardens. And finally, Chinatown, where joss sticks burnt before the tiger faced gods of Kwong Sung and barefooted tailors. WWII changed Darwin dramatically as it became Australia’s northern defence post and a base for army, navy and airforce troops. The implications of the Pearl Harbour attack were not lost on Australia’s military. Although it was impossible to anticipate the speed of the Japanese conquests, it was evident that Darwin could be in danger. Civilians were evacuated, and the troops moved in. Roads, airstrips, camps, buildings and storage areas were constructed.

Japanese troops moved quickly along the Malay Peninsula in February 1942. They soon had British, Australian and Indian forces trapped on the island of Singapore. Britain’s naval base in Singapore protected shipping lanes but could not defend against an attack from the mainland. With two British warships already sunk off the Malay coast on 10 December 1941 and under constant bombardment, the Allied troops surrendered on 15 February 1942. A second more minor evacuation of Darwin took place as the Japanese took over Singapore.

The Japanese high command was encouraged by efforts in Singapore and the attack on Pearl Harbour. They decided to use submarines to attack the Darwin port in January 1942 without any success. Nevertheless, they chose to persist with their aim of denying Darwin’s use to the Allies. An attacking fleet of four aircraft carriers, 11 other warships and six submarines to protect the carriers was assembled. Three cruisers and eight destroyers escorted them.

Darwin was thrust onto the national and international stage four days later. On 19 February, ten American P-40 Kittyhawk aircraft left Darwin, heading towards Dutch Timor. Bad weather forced them back, and they arrived over Darwin just before the first air road by the Japanese. At 9:58 am, 188 Japanese carrier-based aircraft began bombing Darwin. When the people in Darwin saw the Japanese aircraft overhead, they believed that they were the expected American relief force arriving to protect Darwin, until the bombs started dropping. In just thirty minutes, ten ships were sunk, and many aircraft were destroyed on the ground. More than 250 people had been killed and more than 400 wounded. The ten Kittyhawks were Darwin’s only air defence. Unprepared, inexperienced, and out-manoeuvred, nine aircraft were shot down, with four pilots killed in aerial combat. Darwin was severely shelled. The reality of war was brought home to Australia, and the terrifying threat of a Japanese land invasion gripped Australia.

Two hours later, the Japanese returned and severely damaged the RAAF base. While much damage occurred during the first raids on Darwin, several buildings and other infrastructure were damaged or destroyed in attacks over the following 20 months. Darwin was not the only Northern Territory location that was targeted. Katherine, Adelaide River, Batchelor and many airfields and military installations were targeted in over 100 Japanese air missions, which ended in November 1943.

Following the fall of Singapore and the first Japanese bombing raid on Darwin on 19 February 1942, the Military Command in Australia soon realised that a Japanese invasion of northern Australia was a distinct possibility. Up until 1942, Darwin was considered nothing more than a secondary base for allied air and naval operations. But with the rapid fall of allied bases further north, suddenly, Darwin became part of the front line.

The bombing of Darwin signalled a massive build-up of allied troops in the Top End comprising Australian, American and Free Dutch and Polish units. ‘Miles’ camps were erected along the north-south road into Darwin (now known as the Stuart Highway) to fortify Darwin and defend an invading Japanese army. Thousands of service personnel were stationed in the district during 1943. Darwin was never again caught unprepared.

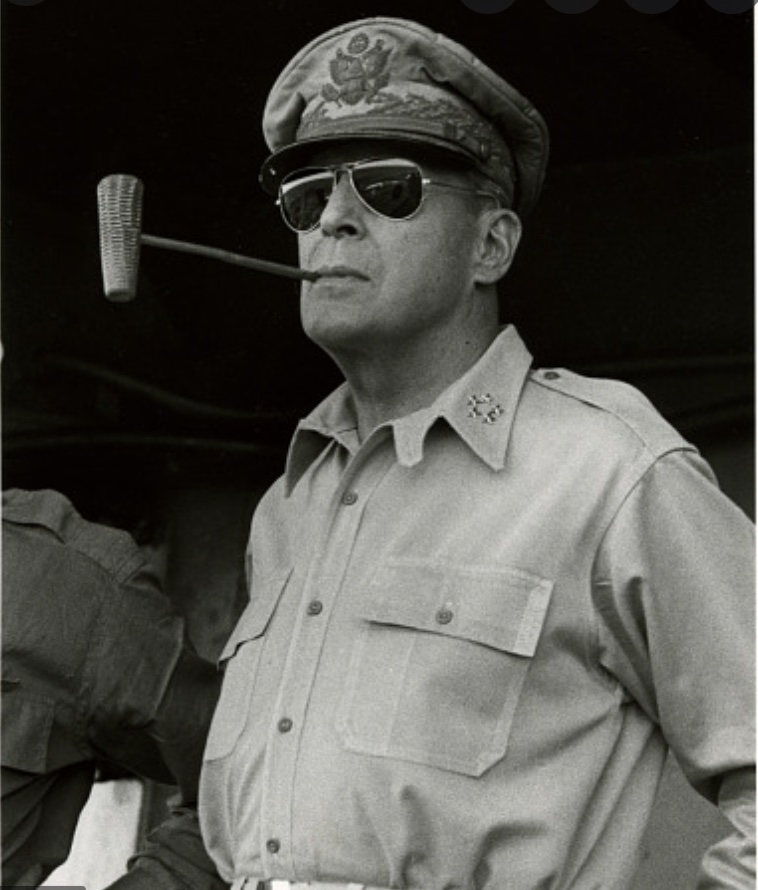

General Douglas MacArthur was the overall commander of the war in the South Pacific. He and his family and staff were evacuated from Coregidor to assume command of the allied forces in the Pacific. Seen as aloof, arrogant and autocratic, he was determined to take the battle to the Japanese to seek revenge for Pearl Harbour and other losses. He wanted a network of Allied bases across Australia’s north to defend Australia from Japanese forces. The Stuart Highway and the North Australian Railway became a corridor to supply the troops.

MacArthur’s South Pacific offensive started in March 1942 and was very strategic and often bypassed Japanese strongholds. The tactic was to isolate well-defended Japanese garrisons and place significant pressure on their supply convoys. By June 1942, Japan had reached the limits of its conquests in the Pacific. They occupied South East Asia and the Philippines and continued to push through New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

There were two important factors that helped the Allies reverse the Japanese dominance. The first was a cryptoanalysis team, based in Melbourne, which had successes in breaking Japanese codes. Their first big success was to intercept Japanese plans to invade Port Moresby. MacArthur at that time thought the Japanese would take New Caledonia next. The fleet radio unit managed to convince MacArthur otherwise and he then prepared to confront the Japanese invasion force sailing to Port Morseby.

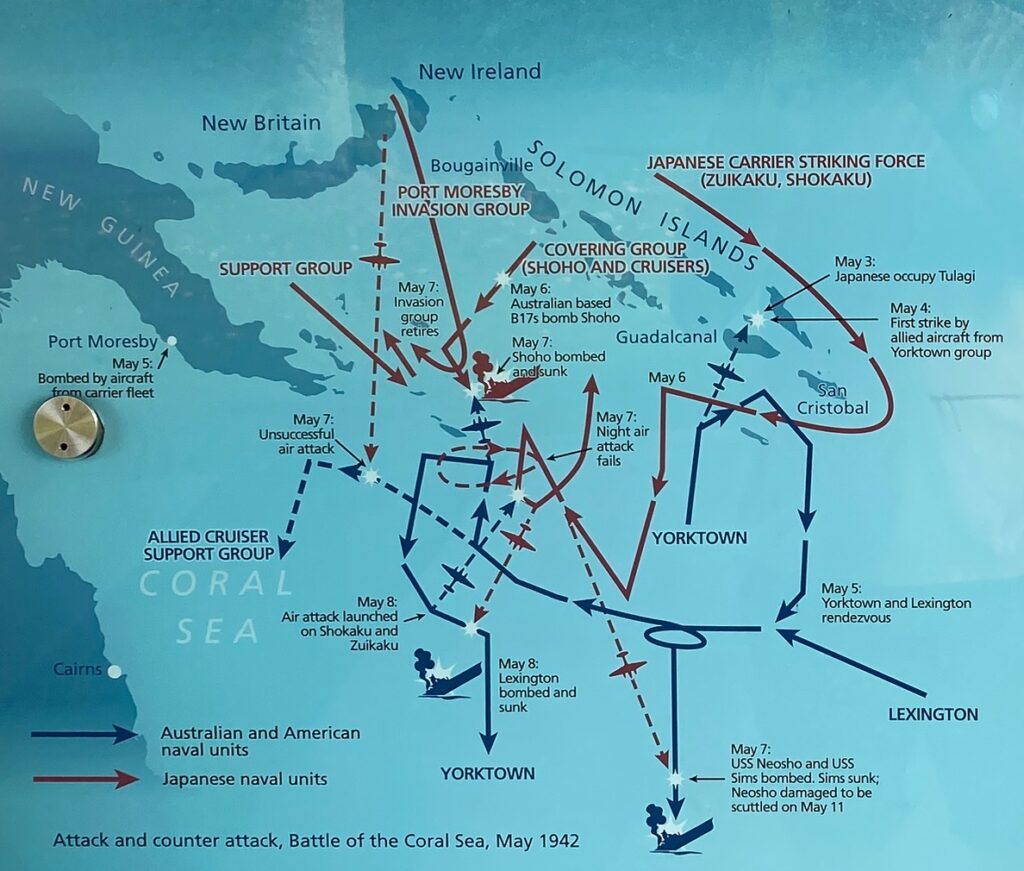

The other was the Battle of the Coral Sea which was one of the turning points in the war. It was the first opportunity for the US Navy to challenge the Japanese Navy. This major sea battle began in the Solomon Islands when US naval and air forces intercepted part of a Japanese invasion fleet heading for Port Moresby. Between 4 and 8 May 1942, a series of air and sea battles were fought in the Coral Sea, just 500 kilometres over the horizon from Cairns. These battles remain the largest ever fought off Australian shores. Remarkably, the opposing naval forces never sighted each other. Aircraft attacked groups of warships in four separate locations. Over 1,500 Japanese and American servicemen were killed or wounded in the battle. The Allies lost the US aircraft carrier Lexington, the supply tanker Neosho, the destroyer Sims and 92 aircraft. The Japanese forces lost the aircraft carrier Shoho, one destroyer, three smaller vessels and 77 aircraft. The Battle of the Coral Sea was highly significant to Australia’s fortunes in WWII. The Japanese intended to capture Port Morseby and Tulagi in the Solomon Islands, isolate Australia, and prevent Allied attacks on Japanese forces in the Pacific. The battle provided a strategic victory for the Allies and a much-needed morale boost to the allied troops by thwarting this plan. For the Japanese it was their first failure in a major battle of the war.

In mid-1943, Port Morseby and its garrison became a critical defence for the Allies. Without it, it was feared Australia would be exposed to attack along a broad front. Japanese forces landed on New Guinea’s north coast in July 1943, seeking to take the port by crossing the Owen Stanley Ranges. In a fighting retreat along Kokoda Trail, a small Australian force delayed and eventually halted the Japanese attack just 70 kilometres north of the port. Aided by reinforcements, the Japanese were pushed back across the mountains by the Australians as they suffered critical supply constraints the closer they got to Port Moresby.

Unfortunately, Australians who grew up after WWII do not seem to appreciate just how threatened Australia was by an invasion by the powerful Japanese nation. Australia was not well prepared for a direct invasion, as the Japanese easily highlighted in February 1942. Part of the problem was that Winston Churchill kept our troops overseas to fight in desperate European battles, such as Greece and Tobruk. Australian troops have received a well-deserved reputation for their fighting abilities during WWI and WWII in Europe and North Africa. But our fighting capabilities were tested protecting our shores. The heroics at Kokoda are well known, but not many other battles closer to home.

Not a great deal of official defence department information about the bombing of Darwin is available for the public, certainly not in the first 50 years after the war. Supreme Court Justice Charles John Lowe held a Commission of Enquiry in March 1942 into the raids on Darwin. His report was only partially released to the public. There has been talk of cover-ups and censorship around the Darwin raids, despite the initial attacks being part of front-page news at the time.

Well told story Robert.

It stirred a few memories of mine.

During a RimPac exercise in 1972, and as a young ensign in the RNZN, I recall being part of the RN’s ‘Far East Fleet’ in the South China sea. It was the final year of Britain maintaining such a fleet and their bases in Singapore and Hong Kong. The fleet passed slowly in line over the “two British warships already sunk” that you refer to. One was the battleship Prince of Wales and the other the battlecruiser Repulse, both significant capital ships. Over 800 sailors died.

This homage had become a time-honoured Navy tradition since WWII as both wrecks were classed as war graves and the act of continual recognition gave a continuance of sovereignty over them, though I suspect in more recent times they have been pillaged by scrap metal ‘pirates’.

A month later the frigate I was serving on visited Manila and, having plotted a course past it and into Manila Bay as a training exercise, I took a ‘tourist’ trip out to Corrigedor Island. It’s an amazing place – in its day it was very fortified with its military history dated back to the Spanish in the 1500s.

Very interesting Robert. Not many people knew about the bombing of Darwin and other places south. We weren’t told during the war.