Crocodiles are ancient reptiles with their ancestors around before the age of the dinosaurs. What makes them so durable is they are perfectly adapted to their environment. The estuarine or saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is most likely encountered in tidal rivers and estuaries, billabongs, and floodplains. However, they can also be found in the open sea. Despite their name, saltwater crocodiles, or salties, are not exclusively found in saltwater. They are commonly found in freshwater pools and rivers many kilometres inland.

Freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstonii) inhabit freshwater rivers, creeks, artificial lakes (like Lake Argyle) and occasionally tidal areas. They are smaller and not considered aggressive.

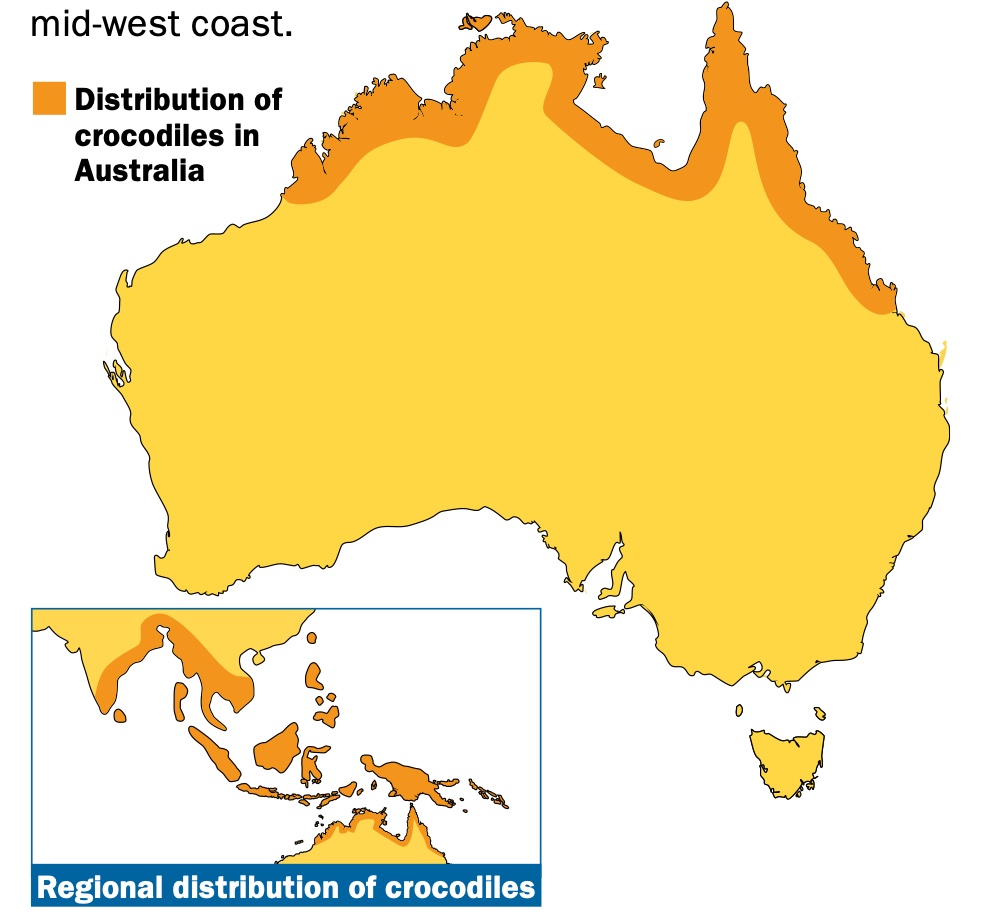

Crocodiles are found extensively throughout northern tropical Australia, extending in the east as far as Townsville, although sightings have been made as far south as Rockhampton and even Maryborough. In Western Australia, known habitat extends south to Exmouth, with occasional records further south to Carnarvon.

Salties are the largest of all crocodile species, growing up to seven metres. They are a dangerous predator. They have a varied diet but mainly feed on fish, waterbirds and occasionally large land mammals, such as wallabies. They are hazardous to humans as they have no fear.

The salty nests from November to April during the northern wet season. The females construct the nests to lay and incubate the eggs. They are territorial and will defend their nests against intruders. The nest is made of vegetation and soil and up to 50 eggs are laid. The incubation period is three months, with only a few hatchlings reaching maturity. Floodwaters can inundate and drown eggs, and young crocodiles are often taken as food by birds of prey, goannas and dingoes.

Aboriginal people have long hunted crocodiles for their meat. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, European settlers in the tropics killed crocodiles. Their hunting was opportunistic and sometimes individual crocs were killed by locals fearful of their safety. But this had no discernable impact on croc numbers.

A crocodile hunting industry developed in Australia due to three main factors. The first was the availability of .303 rifles after WWII that provided the calibre to kill crocodiles reliably. This was a much better option than the lighter rifles. Second, political unrest throughout Africa reduced the supply of crocodile skins, increasing prices through a shortage of supply. Thirdly, crocodile hunting was a dangerous business, and there were many ex-servicemen and some women who were eager for adventure and weren’t ready to settle down into everyday life. Crocodiles could be killed profitably in Australia to fill the demand for skins, and crocodile hunting took off in earnest after 1945.

The profitability of crocodile hunting led to a drastic decline in crocodile numbers. Saltwater crocodiles were the preferred target. They were hardly seen in the waterways across Northern Australia. Freshwater crocodile skin was less valuable because of its texture – they have bony plates in the belly region, making them useless. However, the introduction of a mechanical process to strip the plates from the hide, coupled with the decline in saltwater numbers, meant that freshwater crocodiles also became targets for hunters. As a result, their population decreased markedly in the 1960s.

In 1962, freshwater crocs were protected in Western Australia and in 1970, protection was given to salties. In 1971, complete protection was given to crocodiles in the Northern Territory. In addition, hunting was banned in Queensland in 1974. Across these states and territories, both species have recovered well over the last 50 years, and in fact, the population of salties across northern Australia has soared.

Researchers have been collating data across Northern Australia in the 50 years since hunting was banned. The surveys show a plateauing of numbers in Northern Territory and Queensland but an increase by about three per cent a year in Western Australia. According to Western Australia Parks and Wildlife ecologist Ben Corey, “in the early years of surveys in the King River and other parts of the lower Ord River since 1986, between 20 and 40 crocodiles along 40 kilometres or so of the river were counted. Now, in some years we are counting as many as 150 animals along the same area”. While their recovery is regarded as a success in ecological terms, there are implications for public safety.

There are believed to be 100,000 salties in the Northern Territory, 30,000 in Queensland and a similar number in Western Australia. But the worrying trend is that crocs are getting bigger and edging closer to urban areas. In January this year, wildlife rangers removed a saltie nest at the edge of Palmerston, less than one kilometre from the urban fringe. It is the first time the saltwater crocodile has been found laying eggs within 50 kilometres of the Northern Territory’s capital city.

How do we manage an exploding wild population where humans now have a far greater chance of crossing paths with the apex predator than ever before? In the past, the yardstick managers expected from crocodile attacks was one non-fatal incident a year and a death every three years. Now the numbers are 1.5 attacks annually, both fatal and non-fatal.

In the last 12 months there have been five croc attacks. The most recent, last November, was an attack on a 60-year-old man trying to retrieve a fishing lure stuck in a tree branch on the banks of the Mcivor River near Hope Vale, north of Cooktown. A 2.5 metre saltie mauled and severely injured two soldiers swimming 500 metres offshore in choppy seas last August.

But it is in situations not previously considered at risk where humans are now facing danger. In Queensland last February, a 56-year-old man swimming at Lake Placid north of Cairns was attacked; a twenty-two-year-old survived an attack by a 3.6 metre croc by eye-gouging it when attacked near Weipa; and a 69-year-old yachtsman disappeared on 11 February while fishing in a dinghy off Hinchinbrook Island. His remains were later found inside two crocodiles.

Fourteen people were killed by crocodiles in the Northern Territory between 2005 and 2014 compared to ten deaths between 1971 and 2004. Most attacks are against men mainly because the pursuit that puts them close to crocs is fishing. Relatively few tourists are victims. However, crocodiles encroaching near urban areas are becoming a severe issue in large regional centres in Queensland, where burgeoning residential areas are displacing coastal lowlands, the favoured croc habitat. Half a million people now call Townsville, Mackay and Cairns home.

Problem crocodiles presenting themselves as a threat to humans are dealt with on a case-by-case basis. When appropriate, animals are caught and sent to one of the crocodile farms. They cannot be relocated to another area due to their territorial nature. If released, they return to where they were captured.

Crocodile farms in Western Australia take crocodiles from the wild under license based on a Crocodile Management Program. Despite the restrictions, the crocodile industry is big business. In the Northern Territory, the entire crocodile industry, covering farm-related tourism and retail, egg collection and sale of skins, is estimated to be worth more than $100 million a year, which is a considerable number for the Territory. The Territory government believes tourism values associated with crocodiles were “above and beyond” the value put on the farming industry. The crocodile industry is indeed very unique. It involves farming one of the oldest, least understood and most dangerous predators. It requires the collection of eggs from wild crocodile nests using helicopters to drop in people. Crocodile skin is a much sought-after fashion accessory, with key markets in the United States and Europe. Proponents of crocodile farming believe crocodiles raised in captivity provide the fashion industry with unblemished skin, compared with the battle-scarred skins of wild crocodiles.

It seems that trying to protect people and their pets from the threat of crocodiles is dismissed very quickly by politicians and bureaucrats. In Queensland alone, about 50 crocodiles are sent to crocodile farms each year. They cannot be killed in captivity and live out their days as breeding stock or visitor attractions. However, how humane is stocking crocodiles in high densities to avoid killing them?

There is a strong belief that simply removing the threatening large crocodile only adds to the problem. All it does it create complacency and opens the waterway for smaller, more aggressive crocodiles to move in. The younger males fight each other to claim ownership of the newly vacant territory and they are much more aggressive and secretive. They may not be a big but they’re big enough to kill someone.

The Northern Territory has a much greater population of crocodiles than Queensland. They allow problem crocodiles to be shot, up to 1,200 annually, and about are 250 relocated alive. What is disturbing, however, is the increased reliance on commercial exploitation. The growing leather industry relies on croc eggs harvested from the wild. Earlier this year, the Northern Territory government increased the annual quota of wild-harvested eggs to 90,000. It is turning remote parts of the Territory into industrialised breeding grounds for handbags, briefcases, shoes and fine watch brands. Therefore, it is not surprising that more vocal opponents to culling crocodiles have a stake in the commercial industry.

While in Darwin, we visited Crocodylus Park, and I was appalled at the number of crocodiles kept in small concrete pens. Others were allowed to swim in an open lagoon with barely a hundred square metres as their home territory. Rangers removed 307 crocodiles from Darwin Harbor in 2018 to protect the public from attacks after 344 were removed in 2017. Leading crocodile expert and controversial critic Grahame Webb has argued that shooting the reptiles is more effective than trapping them. Webb said he was opposed to the widespread culling of crocodiles but acknowledged that a small percentage posed a serious threat to people.

Managing crocodiles via relocation is very expensive and ineffective, mainly when managing areas to be free of crocodiles for public safety reasons. In the Northern Territory, if you measure the biomass of crocodiles (that is, size and number), there are 388 kilograms per kilometre. In the 1980s and 90s, kids would regularly swim in the Katherine River. A favourite pastime was to float on pandanus branches from Katherine Gorge to Knotts Crossing. It was considered a safe swimming hole. You can’t do that anymore because of the crocodiles. In 2018, eight crocodiles were pulled from the river, ranging from 2.5 to 4.2 metres. In Queensland, popular beaches in the north are continually closed because of sightings of large crocodiles. One of the more popular beaches at Port Douglas was recently closed due to a five-metre saltwater crocodile. This has an impact on tourism.

Opponents to culling argue it would achieve nothing as it causes a vacuum for other crocodiles to move in. They argue that humans need to educate themselves about crocodiles and learn to live with them. Many say the numbers have plateaued because the food and resources cannot support more numbers. But younger crocodiles are being pushed further inland as the density of crocodiles increases. Bigger crocodiles chase out the smaller, younger ones who need to move further and further upstream.

People who don’t support any culls have only lived in the area for a few years or live in safety in the cities elsewhere. Locals that have had to live with increasing numbers of crocodiles over the last 50 years support a cull. The small percentage of crocodiles that threaten the human population should be dealt with by culling. Like the dingo issue on Fraser Island, or sharks at Australia’s popular beaches, kneejerk political reactions dominate responses when there is an attack.

In Queensland, the Katter Party, with its stronghold in the northern part of the state, called for crocodile safari hunting to be introduced. Member for Dalrymple Shane Knuth said, “crocodile numbers have exploded over the past few decades, which has locals living in fear and tourists afraid to visit Northern Queensland”. But the Department of Environment and Science is firmly against widespread culling of crocodiles, saying “it will do nothing for public safety and image”.

However, licensed hunting through safari tours does exist in the Northern Territory. It is a little-known fact that trophy hunts have returned to Australia since the protection of crocodiles was first introduced during the 1970s. A select few safari operators are licensed and tightly regulated to offer crocodile harvesting by catching and shooting their skins and skulls as trophies. While guests are not permitted to shoot the crocs, they can observe and arrange to purchase the skin or skull for a princely sum of $25,000.

As late as 2014, the Federal government rejected such a controversial plan due to the risk of inhumane treatment. However, the weight of numbers and increasing human threats have quietly swayed the government to reverse its previous decision.

The restoration of crocodiles, a large carnivore, into the ecosystem can create environmental challenges such as biological invasions and disease. For example, a study is underway to try and understand how estuarine crocodiles influence food webs. In North America, similar questions are being asked about the recovery of wolves into the environment. It is essential to use this opportunity to understand better the processes that govern the strength of predator-ecosystems interactions, as long as the studies empirically test the changes using the scientific method, and not just become another example of researchers bleeding the public purse for more funds in the name of a never-ending trail of research for the sake of it.

The issue of crocodiles and humans comes down to whether there are already enough places for crocodiles to live without inhabiting the rivers, beaches and stormwater drains of the major population areas where they pose a real threat.

In Queensland, crocodile populations could be limited to the waterways of the Cape York Peninsula, an area of about 115,000 square kilometres or half the size of Victoria. Once this is understood, a focus could shift to a targeted removal from tourist areas such as the Whitsundays, where crocodiles are a real problem.

The issue is about common sense, isn’t it, or is that a rare commodity these days? It is now very difficult to sustain the argument that crocodiles need to be conserved. Indeed, a start would be acknowledging the danger crocodiles pose and a focus on devising a way of protecting humans over crocodiles in a small portion of built-up coastal towns and cities, major tourist areas and popular fishing spots. A start would be to shift responsibility for managing the problem out of the cities, such as Brisbane, to northern Australia. Any awareness program over crocodiles should be complemented with a program to manage there risks.

Time to do large scale culling

Dear Robert

An interesting article, about a difficult and controversial subject. There will never be agreement between those with a primary concern for protecting human life, and those with a primary concern for protecting biodiversity (which does not include humans). Arguments about bushfire management fall into the same category.

Needless to say, those most concerned about protecting crocs are rarely exposed to them and those most fiercely opposed to prescribed burning usually live in leafy suburbs where bushfires never occur.

One thing you may not have heard about is “salties as practical jokes”. A friend of mine tells me that a favourite joke in Darwin is to capture a small (say 1 m long) salty and, under cover of darkness, insert it into your neighbour’s swimming pool. This brings some unexpected excitement to the early-morning dip.

Roger

Can’t wait for you to do a similar piece on sharks, whose population I’ve watched explode over the last decade of fishing the GBR and east coast of NSW, despite claims of their imminent demise.

Steve, I can see a guest blog coming!

A very interesting article thankyou. Anybody travelling to North of Australia should certainly make themselves very aware of these facts on the crocodiles!

It appears a well managed cull is long overdue if the growth of urban areas near waterways are getting larger.