“I don’t like them [camels]…but from my point of view I reckon they were the best animals that ever looked through a collar”. Camaleer ‘Stockwhip Jim’ Clarke

Australia’s outback covers more than six million square kilometres or almost twice the size of India. As the coastal areas were first settled in Australia, questions remained about the interior. Expeditions were organised to fully explore that unknown area. However, the expeditioners experienced punishing conditions. There was initial confusion over a map from the early 1800s showing a vast inland sea in the centre of the country. But bit by bit, explorer by explorer, the interior of the continent was discovered and mapped.

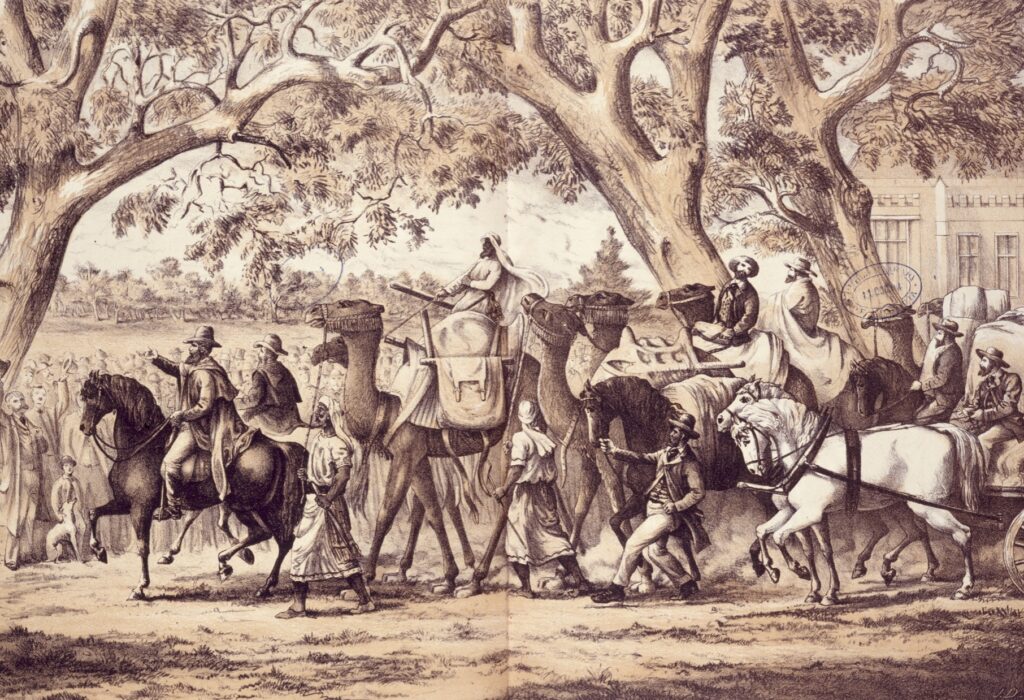

The hot and dry interior required hardy animals to transport goods over long distances. The first recorded introduction of the camel to Australia was in 1840 from the Canary Islands. However, it was shot in 1846 after it caused the death of explorer John Horrocks. It wasn’t until 1860, on the Burke and Wills expedition, that camels were first used, as well as horses, to transport goods. The second in command on that expedition, George Landells, had previously recommended that the Victorian government use camels for their state-sponsored explorations to the interior. Landells had worked as a horse trader in India. He argued they were ideally suited to the Australian outback and was authorised to borrow money from the Indian government to purchase the animals and engage the services of camel drivers. Twenty-six camels departed Melbourne on that ill-fated expedition. Most survived. Of the six taken by Robert Burke, William Wills, Charlie Gray and John King when they left the Cooper Creek depot, three were eaten on their way back from the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Although the Burke and Wills expedition had a tragic outcome, it confirmed the usefulness of camels to carry goods throughout the outback and survive the difficult conditions. Adelaide’s Thomas Elder arranged the first mass import of camels into Australia in 1865. Ernest Giles, known as the “last of the Australian explorers”, led five expeditions into the unknown western interior between 1872 and 1876, the last two on camels. The first time he used camels, he travelled 220 miles in eight days without giving water to the camels. Giles later went from Bunbury Downs to Queen Victoria Springs in Western Australia, a distance of 325 miles in 17 days. He gave each camel one bucket of water after the twelfth day. A hundred camels were used for the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line in the early 1870s. J. W. Lewis also used camels as part of his survey of the country north east of Lake Eyre in 1874-75.

As the interior was explored and it was confirmed there was no inland sea, outback goldfields were discovered, settlements were established, and major transport routes were created. The distances were great, and the traditional packhorses and bullocks lacked the staying power and often died through lack of water and feed.

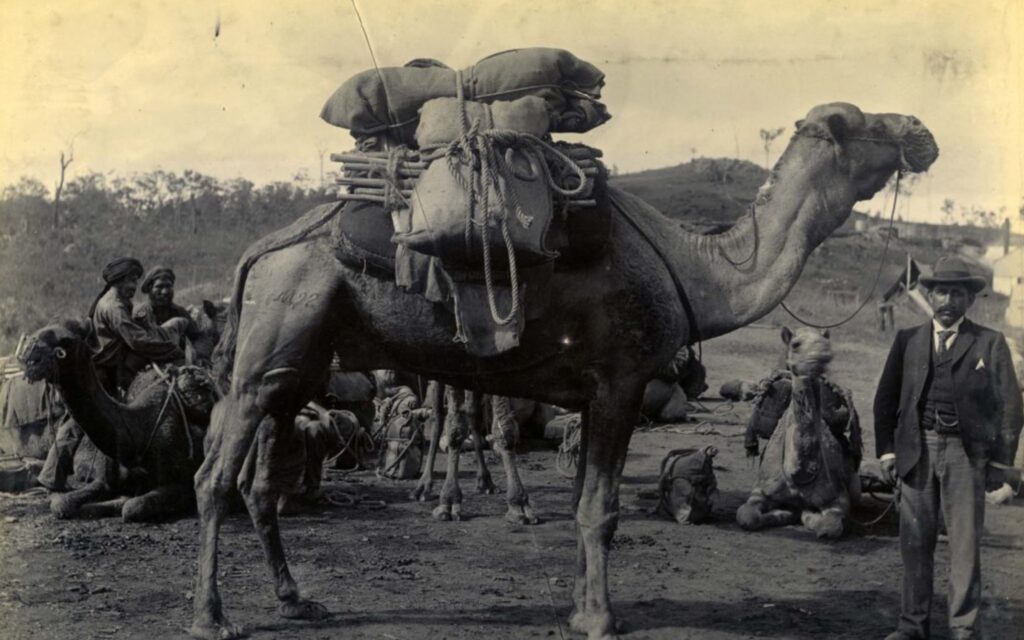

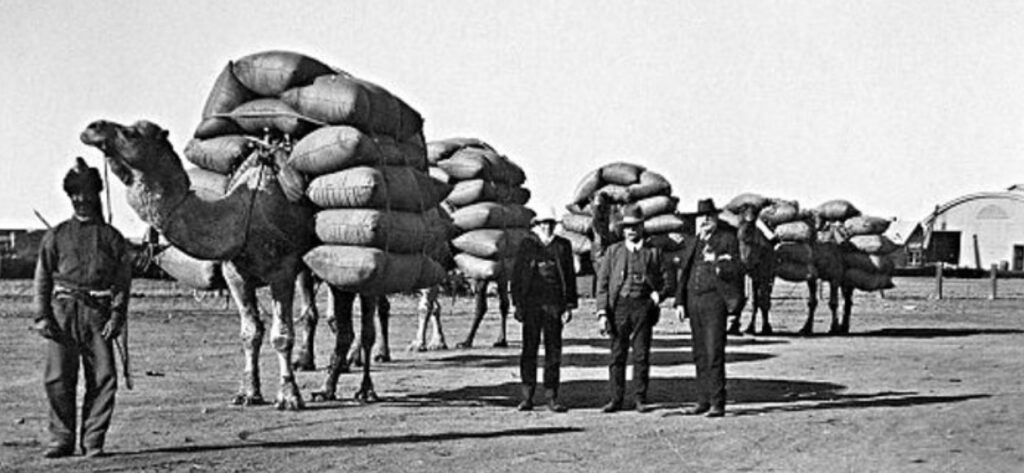

Camels were the preferred form of heavy haulage in Australia’s arid and semi-arid country because they could eat coarse scrub and go for several days without food or water, unlike teams of horses, mules, donkeys and bullocks. They could travel up to 40 kilometres a day, and each camel could carry up to 600 kilograms. They were loaded with everything and anything: construction materials, supplies, mineral ores, barrels of water to drought-stricken areas and wool bales. They were a common sight in some coastal towns, such as Onslow, as they carted bales of wool clip to the jetty.

Camels can conserve water by reducing sweating and concentrating their urine. The camel’s body temperature rises nearly three degrees before they start to sweat. As a result, they can lose much of their body weight without ill effects and return to normal when they are able to drink. Their coat acts as an insulating layer in winter and reflects radiant heat in summer. They have tough skin to withstand thorns and spinifex and a padded foot adapted for movement on sand and gibber plains and it insulates their feet from the hot earth. Camels have a large flat foot and usually travel in a straight line and in a single file. Over a period of time, their hoofs would leave a distinct track or pad. Although it is nearly 100 years since their demise for transport, two distinct camel pads are still clearly visible on the outskirts of Mount Magnet, according to locals.

Between 1865 and 1920, about 20,000 camels were imported from the Arabian Peninsula, Afghanistan and an undivided India (today India and Pakistan). Experienced handlers were required for the teams of camels, and British entrepreneurs imported at least 2,000 from the same areas as the camels. They were colloquially known as “Afghans” or “Ghans”. According to Anna Kenny, co-author of Australia’s Muslim Cameleers: Pioneers of the inland, 1860s -1930s, the cameleers “opened lines of supply, transport and communication between isolated settlements, making the economic development of arid Australia possible”, and all before railways had appeared across the landscape.

Many rest stations opened up across the country where camel teams converged as they moved from one state to another. Centres such as Marree in South Australia opened supply lines to isolated communities further inland or further north.

The camels brought into Australia were mainly the one-hump species (Camelus dromedarius) found in hot deserts overseas. Australia soon began breeding their own camels. The first of many camel studs were set up in 1866 by Elder at Beltana Station in the Flinders Ranges. These studs operated for about fifty years and provided high-class breeders superior in quality to the thousands more imported from overseas. Imports from Palestine and India continued until 1907 as there was a need for large numbers of cheap camels. Dromedary Hills, near Mount Magnet, was first recommended by Alfred Canning as a suitable depot and breeding area for camels. A 3,000-acre reserve was fenced, and by 1911, light riding or buggy camels were bred there. Their better quality saw them exported around the world. The camel breeding station closed in 1932.

By the 1940s, the camel industry was all but gone in Australia. The arrival of the internal combustion engine and an interconnected motorised road and rail transport made the camel obsolete pack carriers as they couldn’t compete with those goods vehicles. They were either shot or left to roam wild. Their descendants number an estimated 300-500,000 that now roam in the outback with about 50 per cent in Western Australia, 25 per cent in the lower Northern Territory, and 25 per cent in western Queensland and northern South Australia. They have managed to thrive in these arid regions compared to other introduced animals.

Camels today are seen as a major threat and impact to the interior environment as they are left to breed unchecked in their favoured landscape. This population is a legacy of the challenges of transporting goods across Australia’s arid inland during the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. They played a significant role in the development of outback Australia in the nineteenth century, acting as ships of the deserts as they plied their way through the very inhospitable conditions.

Robert. This story needed to be told. I can see you publishing these historical stories in a book. Stories from our past by Robert Onfray. Keep up the good work. John

Thanks John. It may be something to pursue, as well as the other books I am keen to write!

Hi Robert, I’m researching my family for the purpose of writing a book about my grandmother who travelled as a child with her family circa early 1900’s on a camel train supposedly from Warragul, Victoria to Coolgardie WA.

Despite my research, I am unable to ascertain if the journey began in Victoria or if the family had to make alternative arrangements to reach South Australia before being able to pick up a camel train heading West.

In your research, are you able to confirm what route the camel trains would have taken or if they did start in Victoria?

Hi Gail

Unfortunately my research didn’t go to that level. I am afraid I am unable to answer your question. Perhaps you could ask the question on some of the history pages on Facebook, such as Victorian History.