After European settlement, Surrey and Hampshire Hills were utilised for grazing and farming under the ownership of the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.). The only significant industrial development on those estates was the construction of the Emu Bay Railway. After ownership changed hands to companies associated with Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM), the focus turned to forestry and major infrastructure works, including the construction of roads and the harvesting of timber. From the late 1980s, both properties were subject to the introduction of industrial-scale eucalypt plantations, which culminated in the siting of a significant industrial plant – the Hampshire woodchip mill, first built in 1995.

However, there was a little-known proposal for major smelting works on Hampshire or Surrey Hills in the late 1890s. It didn’t go ahead, but it could have influenced the future direction of those lands if it did.

In 1890, prospector Alfred Conliffe discovered a gold-bearing deposit on Mount Hamilton, immediately north of Mount Read. The Mount Read Mining Company was formed to work the deposit, which was a great source of lead-zinc ores. In 1894, Mount Read hotelier and prospector, Thomas Goldie, located a more important discovery of silver below the existing Mount Read Mine. Later that year, the Hercules Gold and Silver Mine Company (HGSM Co.) was formed to work the discovery in a forest in its pre-European state, with simply a rough pack track from the railway terminus at Dundas to Mount Read. Mining historian, Nic Haygarth, has written an excellent article about this discovery and the formation of the company. The Chairman noted (with a bit of poetic licence to talk up the mine’s prospects, no doubt) that almost immediately after operations started, “gold and silver-bearing ore of exceptional richness was discovered”. Several adits were driven into the side of the mountain, which “exposed enormous bodies”.

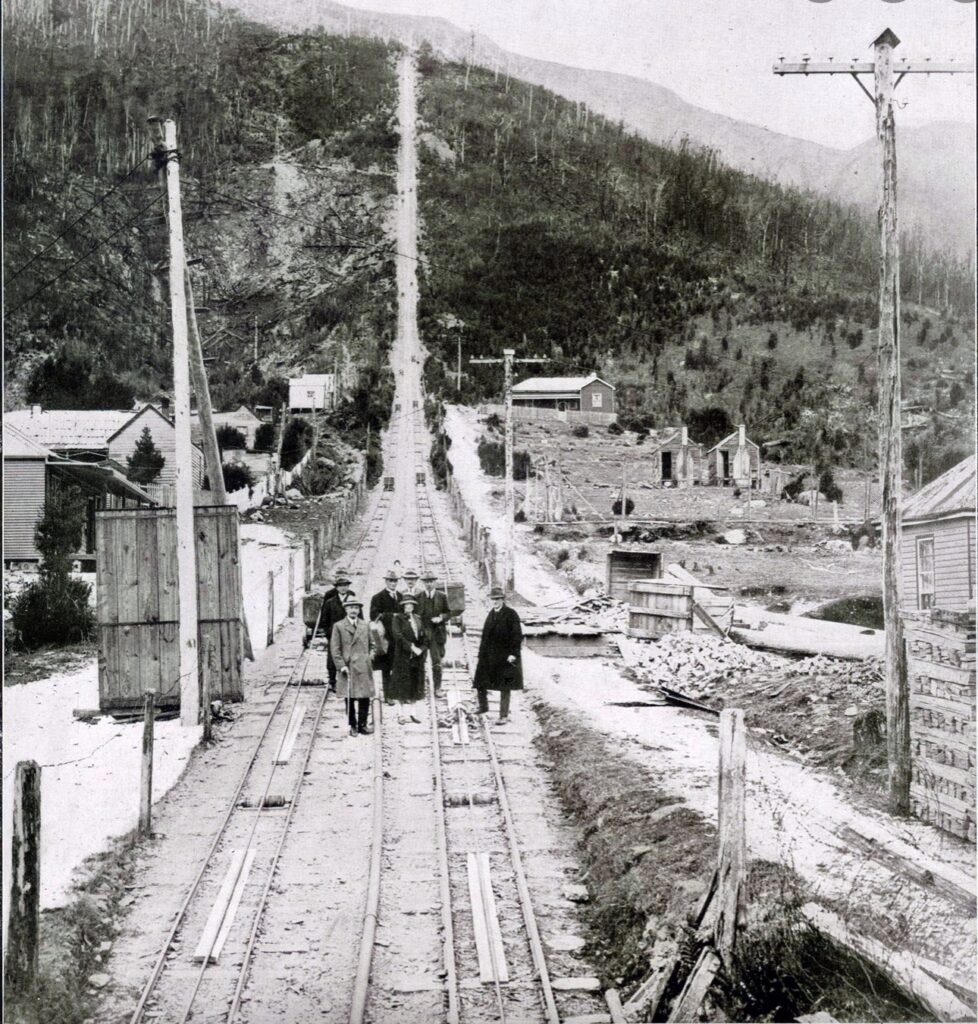

The original settlement was initially known as Deep Lead. However, a town soon developed on the lower western reaches of Mount Read to house the workforce for the mine. It was called Williamsford, named after a former manager of the Mt Read mine, Mr Luke Williams. It was about seven kilometres south of Rosebery.

The Hercules mine developed to full production by 1900. A unique haulage system was built on the western slope of Mount Read. The two-foot aerial ropeway was a self-acting haulage line where loaded wagons travelling downhill to Williamsford pulled the empty wagons uphill via cable and gravity to the mine. It was one mile long and over 500 metres high on the slopes of Mount Read, with a maximum gradient of 1 in 5. It was claimed to be the largest and steepest self-acting tramway of its kind in the world.

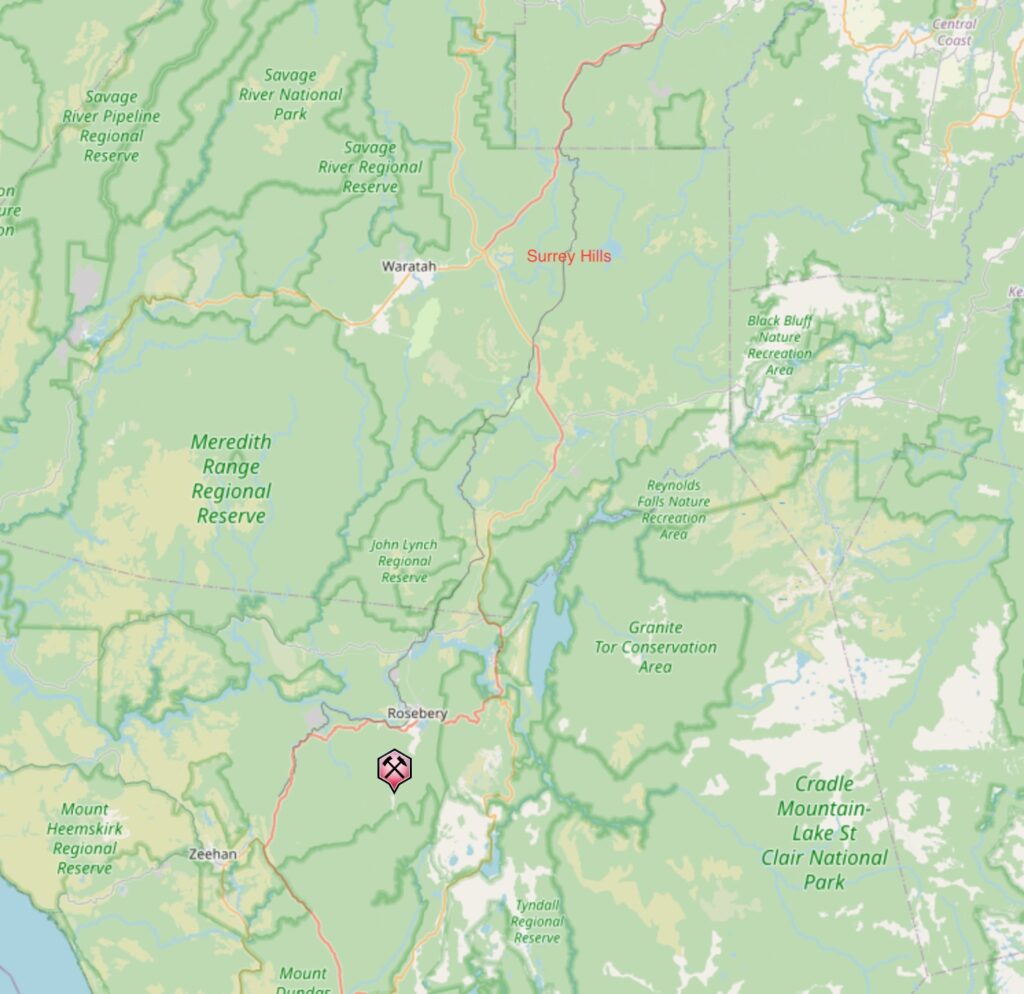

In the 1897-98 Report of the Secretary for Mines, the HGSM Co. considered erecting smelting works close to the Emu Bay Railway, about 22 miles from Burnie. Sulphide ore from the Hercules mine contained too much zinc to be smelted by itself. Instead, they proposed to drown the zinc by mixing it with clean lead ores and the gossan from the mine. It was reported a suitable site had been chosen, with limestone and ironstone close at hand.

At the Annual General Meeting of the HGSM Co. in March 1898, the directors advised they had received two offers to purchase the output of the mine. One was by the Smelting Company of Australia with their smelter based in Dapto, New South Wales. The Smelting Company of Tasmania was the other. They were about to build metallurgical works near Zeehan. The latter wanted an agreement to buy not less than 1,500 tons of ore per month – 750 of dense sulphide, 500 tons of gossan, and 250 tons of antimonial ore.

James Norton Smith, the VDL Co’s Chief Agent in Tasmania, went to England in June 1898 to brief the Court of Directors on the VDL Co’s. state of affairs. He told them that he had received a definite proposal from the HGSM Co. to have water rights and land for the erection of a large smelting works. HGSM Co. considered establishing their own smelter and were looking at possible locations, including land at Hampshire and Surrey Hills.

Correspondence of the VDL Co. in July and August 1898 confirmed that the HGSM Co. applied to purchase 100 acres of land on the Loudwater Creek at Hampshire Hills to erect smelting works. Upon hearing this application, the Court of Directors in London were concerned about the pollution of the waters nearby and they didn’t give Norton Smith any clear direction on whether they supported the application or not.

In the meantime, Norton Smith entered into negotiations with the HGSM Co. to establish the smelter on VDL Co. land. A couple of months later, he reported to the directors he had negotiated a 60-year lease with the mining company to build a smelter in the vicinity of the Wey River bridge for £25 per year. Norton Smith took the opportunity to express disappointment and frustration at the director’s initial response and “regretted that the Court looks upon the tentative agreement [for a smelter] with aversion”. Nevertheless, Norton Smith hoped that the development would lead to a town on Surrey Hills “which has hitherto been comparatively useless” and saw an opportunity to promote the interests of the VDL Co.

The disapproval of his tentative agreement with the HGSM Co. and other issues led Norton Smith to question whether the Directors had complete confidence in his management. It was at a time when the relationship between Norton Smith and the directors was very strained.

In the end, the HGSM Co. decided to send their ore to Zeehan for smelting. The VDL Co. directors wrote they were “pleased to see that the Hercules Company has entered into a contract for the supply of 130,000 tons of ore to the Tasmanian Smelting Company of Zeehan to be delivered at the rate of 3,000 ton per month; as the whole of this must be carried over the Emu Bay Railway it certainly looks as though the prospects of that company are distinctly improving”.

After deciding to send ore to Zeehan, Williamsford was connected to Zeehan and its smelter by the 29-kilometre North East Dundas Tramway in 1898. It was a two-foot gauge tramway or mountain railway. There were numerous sharp curves down to 1-11/2 chains radius in the mountainous sections on a grade of 1 in 27.5. The tramway required powerful engines, and supposedly the heaviest two-foot gauge engine in the southern hemisphere was used on the line. It was called Hagan’s system patent coupled bogie locomotive, which had 12 wheels, ten of which were coupled in two groups and a pair of leading bogie wheels.

The new Chief Agent of the VDL CO., Andrew McGaw, started in February 1903. The directors wrote a somewhat strange and contradictory letter to him later that year, “an application was made by the Hercules Company for the erection of Smelters and works near the Loudwater Creek on the Surrey or Hampshire Hills, somehow or another the matter was dropped, most probably owing to apathy in the late management; so far as we know they have not yet arranged for the erecting of works and it it[sic] quite possible that they may be open to renew the application. It certainly would be desirable if we could secure the erection of large works at or near this Creek and if an opportunity occurs you might make an effort to re-open the negotiations.” The letter would never have been written if they had acted decisively previously and approved Norton Smith’s lease with the HGSM Co.

An economic downturn affected operations and led to the closure of the Zeehan smelter in 1913. The Hercules mine was forced to close. The Electrolytic Zinc Company purchased and refurbished the Zeehan smelters in order to process the complex Rosebery and Mt Read ores. The mine was re-opened in 1920, and it operated until 1986. They sent the ore to a concentrator in Rosebery. Metal concentrates were then forwarded to the port of Burnie via the Emu Bay Railway.

Since the closure in 1986, the area at Mount Read has been deserted, and Williamsford is now a ghost town. However, the ruins of the haulage system remain. Over this period, ore production exceeded 2.5 million tonnes with an estimated value of $1 billion in today’s figures.

The Hercules mine gained a short reprieve in 1996 when Mancala Pty Ltd reopened the No. 7 level. Then, in 1999, mining ceased for the last time after three years and almost 200,000 tonnes of ore production.

The attraction of Hampshire or Surrey Hills to support a significant smelter operation highlighted the importance of the Emu Bay Railway for the western minefields. Surrey Hills had good flat land with plenty of water which could support industrial enterprises. The Court of Directors, however, were justified in showing concern for the waterways on Surrey Hills. This was because the Hercules mine ore was very complex. Max Heberlein, the great metallurgist at the Tasmanian Smelting Co at Zeehan, couldn’t separate the zinc. There were only a few silver-lead operations, such as Magnet, North Farrell and the remaining Zeehan mines, that could provide any ore to the proposed smelter. The biggest issue, however, would have been the pollution from the smelting process and the whole project most likely would have been a complete disaster. The directors failure to provide any initial support for such a project led the HGSM Co. to seek other options for processing their ore.

If the smelter went ahead on Surrey Hills, it is worth contemplating whether the fortunes of the VDL Co. may have changed at that time. A town similar to Zeehan may have developed, which would have changed the small number of land sales and leases that occurred in the first two decades of the twentieth century. If that is the case, the Surrey Hills estate that we know today as a large contiguous block would have been subdivided into smaller parcels supporting the new town, and the land may never have attracted the forestry interests, and the Burnie pulp and paper mill may never have resulted. In that case, the fortunes of Burnie itself would have been very different.

However, the alternative view is that if a smelter did go ahead, it probably would not have prospered, and most likely only last a few years. Its legacy would have been an industrial scar and environmental damage.

Your story about the Hercules incline reminded me about the Denniston Incline in NZ, which was certainly steeper and possibly longer. See video at https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/7429/the-denniston-incline. More information below:

Denniston Incline (1879) Hell on earth halfway up ‘The Hill’

The boosters called it the ‘Eighth Wonder of the World’. The poor sods forced to slog away in the mines up ‘The Hill’ sang a different tune:

‘Damn Denniston

Damn the track

Damn the way both there and back

Damn the wind and damn the weather

God damn Denniston altogether.’

They had reason to complain, for Denniston was a miserable hole, a gimcrack clutter of corrugated iron and weatherboard buildings clinging precariously to a bleak plateau. Thick fog could hang around for weeks on end, as could steady drizzle. In between times it bucketed down, yet little grew here apart from rust, emphysema and the politics of dissent. The soil was so thin they had to send bodies down the incline for burial elsewhere.

Denniston (named after R.B. Denniston, the company’s surveyor and colliery manager) was the bleak jewel in the Westport Coal Company’s crown. It was also the country’s most productive coalfield. From its offices in Water Street, Dunedin, Westport Coal collaborated with the Union Steam Ship Company to dominate the colony’s fuel and transport industries. Between 1879 and 1967, 13 million tonnes of coal was sent down the incline to Union Steam Ship Company colliers at nearby Westport.

It was a technical triumph. The incline plunged precipitously, 548 m in a distance of just 1670 m, with some grades as steep as 1 in 1.25 (80%). Two water-operated brakes, Upper Brake and Middle Brake, slowed the progress of the counter-balancing wagons (i.e., descending full wagons pulled up empty ones) down the two inclines to the railhead at Conns Creek.

The regenerating bush is reclaiming the upper (number one) incline, but the lower (number two) incline can be admired from a nearby walking track. You can see rusting wagons, wire by the kilometre, stretches of track, and an impressive drive tower at the top of the incline. A few people still inhabit the township, where the Friends of The Hill have restored the old schoolhouse. Tracks lead to other former mines and features. Keep to them and watch out for old shafts.

I recently bought some music in a loose leaf leather book initials MCM. Inside some of the music is marked Mary C Moxon, Hercules House, Williamsford. I’d be interested to know if a Moxon was associated with this mine.