On 19 November 1941, on the Indian Ocean off the Western Australian coast, the Royal Australian Navy’s greatest warship, the HMAS Sydney II, was sunk by a disguised German raider. It was and still is the worst naval disaster in Australia’s history. All 645 officers and men on board HMAS Sydney II were lost at sea, representing 35 per cent of the Royal Australian Navy personnel killed in WWII. There were 317 German survivors from HSK Kormoran out of a complement of 390. They had abandoned and blown up their own damaged ship and made it to shore. The Germans gave their accounts of the battle and told of seeing the Sydney destroyed and ablaze, drifting away into the night.

HMAS Sydney II was one of three modified British Leander Class light cruisers purchased by the Royal Australian Navy just before WWII. Early in the war, she gained notoriety operating as part of the navy’s Mediterranean fleet. In July 1940, against superior odds, under commander Captain John Collins, Sydney engaged and destroyed the Italian light cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni and damaged another, the Giovanni Delle Bande Nere. In February 1941, Sydney was recalled to Australia and assigned operations off Western Australian waters under new commander Captain Joseph Burnett, undertaking routine patrols and convoy escort duties. On 11 November 1941, she sailed from Fremantle to escort the troop ship Zealandia to the Sunda Strait carrying troops from the Australian 8th Division to Singapore. She handed over her charge to British cruiser HMS Durban on 17 November 1941 and left to return to Australia.

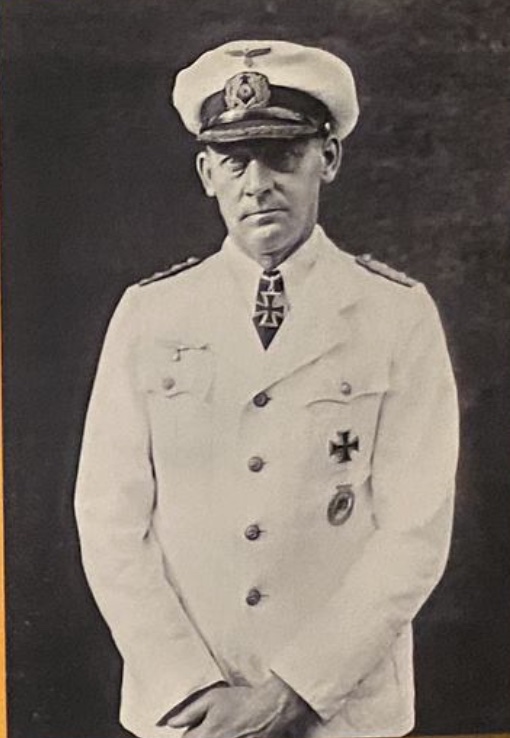

The German auxiliary cruiser HSK Kormoran was originally a merchant vessel. It was acquired by the German navy following the outbreak of WWII and converted into a disguised raider. The ship’s true identity was hidden with concealed weapons and ingenious systems to deploy them for surprise attacks. It had assumed various disguises, taking on the identities of known merchant vessels to avoid detection. Under the command of Captain Theodor Anton Detmers, the Kormoran’s instructions were to search the Atlantic Ocean for targets of opportunity and then move to the Indian Ocean and seek out Allied merchant shipping, to disrupt trade and supplies with additional orders to lay mines around one or more Allied ports in India or Australia. Over the previous year, it had successfully sunk ten Allied merchant ships.

On 19 November, both vessels were sailing off the coast of Carnarvon, Western Australia, approximately 120 nautical miles west of Steep Point. The Kormoran planned to lay mines on shipping routes near Cape Leeuwen and Fremantle. After wireless signals were detected from the Australian warship HMAS Canberra escorting a convoy in the area, Detmers sailed further north to mine Shark Bay. That decision would mean two war ships would meet by chance. As the Kormoran was heading north, the masts of a cruiser was sighted and it altered course into the sun to escape, even while setting to action stations. Sydney spotted the German ship around the same time and changed its southward path to intercept the fleeing ship.

The Kormoran was disguised as the Dutch ship Straat Malakka. Burnett challenged the German vessel’s identity while closing in. Burnett was required to destroy raiders, but supply ships were to be captured. To tell the difference between the two, however, was extremely difficult without close inspection. He sent searchlight signals which were not answered because the Germans did not understand the Morse code. Burnett was not satisfied with the mysterious vessel’s responses. They were slow and unclear for a ship supposed to be a harmless Dutch trader. He issued a final challenge to reveal her secret call sign when the ships were about one nautical mile apart.

By allowing Sydney to get so close and thus lose its advantage and put it under extreme danger, it is believed that Burnett assumed he was dealing with a merchant ship that was unarmed. He didn’t know that the Kormoran had set a trap by stealth and sought the advantage of close proximity and to fire first from its hidden guns. The Germans opened fire on Sydney, and a battle ensued from which neither ship survived. The battle took place in a remote, deep-water location with no witnesses. Sydney was due to return to Fremantle on 20 November, but the cruiser and her men were never seen again.

Given various feasible explanations for a delayed arrival, there was little immediate alarm when HMAS Sydney did not arrive in Fremantle on time. On the evening of 23 November, the Navy Office signalled Sydney to request her estimated time of arrival. Later that night, Sydney was instructed to break radio silence and report. There was no reply. An air search began the next morning, far south of where the battle had taken place. Later that day, a tanker reported she had picked up 25 German sailors from a raft off Shark Bay. The realisation that this was connected with Sydney’s disappearance sparked a huge air and sea search. Unfortunately, there was little chance of survival for the five days that passed before the search began in earnest. No survivors from the Sydney were found.

On 26 November, telegrams were sent to next-of-kin stating that their relatives were “missing as a result of enemy action”. However, naval censors advised the media that no announcements relating to HMAS Sydney be made. Prime Minister John Curtin officially announced the loss of Sydney on 30 November.

“Information has been received from the Australian Naval Board that HMAS Sydney has been in action with a heavily armed enemy merchant raider…No subsequent communication has been received from HMAS Sydney, and the Government regrets to say that it must be presumed that she has been lost…The next of-kin, to whom the Government and the Naval Board extend the deepest sympathy, were informed…”

The government lifted censorship restrictions on newspapers, but radio stations had to wait 48 hours before broadcasting the news to avoid alerting other German ships in the area.

Commander Victor Ramage wrote to the Admiralty on the fate of Sydney in December 1941:

“My own view is that she sank in flames about 2300H or earlier, and that such of her gallant crew who were alive at this time were swallowed up by the sea”.

Across the nation, there was shock, grief and disbelief that Australia’s most decorated warship had vanished. Nine months earlier, the Australian public had celebrated Sydney’s outstanding operational achievements on her return from the Mediterranean.

With no ship and no survivors, the tragedy led to considerable and often bitter public controversy. Many Australians did not believe the Germans account of the battle, particularly their claim that Sydney acted in a manner not expected of an Australian warship under the command of a competent and experienced officer. Many could not believe that a modified merchant ship could destroy one of the Australian navy’s most successful cruisers, which had much superior firepower. Equally, for the Royal Australian Navy, the loss of its ‘glamour ship’ of the fleet was a massive blow to morale. It was claimed that after establishing the German’s account of the battle, the Germans had acted illegally by firing before the Kormoran had raised her battle ensign using false signal flags to indicate a medical or engineering emergency and lure the Sydney closer. Detmers’ autobiography claimed it took six seconds to lower the Dutch flag, raise the German war ensign – a flag hoisted on a warship’s mast just before going into battle – decamouflage and start firing.

In the years that followed, many more questions were asked, with various theories promulgated to explain what had happened. The main unanswered questions were twofold – what induced Sydney’s Captain Joseph Burnett to forego his long-range gunnery superiority and bring his ship so close to the Kormoran? And why were Sydney and its sailors lost practically without any trace when so many Germans survived?

Some Commonwealth records relating to the loss of HMAS Sydney were made available in the 1970s. Until then, the public had little information to rely on, with some published works relying mainly on secondary sources. Two publications in the early 1980s – Who sank the Sydney? by Michael Montgomery and HMAS Sydney: fact, fantasy and fraud by Barbara Winter – focused attention on these newly released primary source materials such as official files, personal papers and ‘secret’ documents.

Over the next decade, the story about HMAS Sydney’s ill-fated last battle was hotly debated. A growing community of professional and amateur researchers sought answers to questions surrounding this tragic event. Suspicion reigned, mainly as records relevant to the action and its aftermath were not in the public domain because they were still subject to wartime secrecy provisions or located in files that were still to be examined by the National Archives. Pressure was brought to bear for a systematic archival search of the records that may have a bearing on the controversy. A search of twelve government departments or agencies most likely to have material was carried out by Richard Summerrell. He published The Sinking of HMAS Sydney: a guide to Commonwealth Government records in 1997.

As time has passed for the families who lost brave sons, fathers, and husbands, there was growing speculation and innuendo about precisely what happened to HMAS Sydney. A series of books added fuel to the debate. To quell this debate and understand what happened to HMAS Sydney, a Joint Standing Committee Inquiry by the Australian government was called in 1997 and they released their report in 1999. What hampered the Inquiry was that no previous formal naval inquiry or public inquiry was held, either immediately after the disaster or in the post-war period. While an investigation in December 1941 was never going to happen given the declaration of war by Japan and Australia’s increasingly threatened position, the lack of a formal review after the war meant that the opportunity to collate the evidence more readily available and known was lost. Consequently, more books speculating about the battle were published.

Wesley Olson’s Bitter Victory: the death of HMAS Sydney was published in 2000. He re-examined the evidence, including comparisons with similar naval engagements and sinkings, which supported the accepted view of the battle. Glenys McDonald’s 2005 work Seeking the Sydney: a quest for truth focused on accounts from people who claimed to have observed the battle or been involved in the search, rescue, or interrogation to compile an oral history of the engagement and its aftermath. Her research led her to believe that the battle had occurred much closer inshore than claimed by the Germans. The 2005 book Somewhere below: the Sydney scandal written by John Samuels took an extreme view on the alternative engagement theory by arguing that Sydney was sunk by a Japanese submarine with little or no involvement by HSV Kormoran. Samuels’ work was polarising. He dismissed the evidence supporting the accepted view as part of a cover-up. His detractors believed the book only served to bring suffering to the relatives of those killed, notably when Samuels claimed that the Sydney crew were massacred.

The Finding Sydney Foundation was established to raise funds with the principal aim to find the wreck of HMAS Sydney, to finally commemorate its missing crew, and allow closure to the families of those lost. They formed an alliance in late 2004 with the highly successful shipwreck investigator David Mearns, who had taken a keen interest in finding both shipwrecks. One of the 1997 parliamentary inquiry recommendations focused on the practical outcome of finding the submerged wrecks and perhaps coming to some firmer conclusions about why none of Sydney’s company survived the engagement with the Kormoran. In 2005, the federal government provided a $1.3 million grant to the Foundation to support a large-scale search. The Western Australian and New South Wales governments added another half a million and a quarter of a million dollars respectively. It was not until the federal government approved another $2.9 million in October 2007 that the search could proceed. However, because of the prohibitively expensive scan sonar equipment used to find the wrecks, the total funds only permitted the chartering of the survey vessel SV Geosounder for 45 days. The objective was to find the Kormoran first using a defined search area and then use its location as a reference point to find Sydney. The search area was equivalent to the size of the Australian Capital Territory.

The Kormoran wreck was found within two weeks on 12 March 2008, west of Shark Bay at a depth of 2,500 metres. Mearns refined his search area based around the Kormoran, and four days later, he found the wreck of HMAS Sydney, 22 kilometres away.

A Remotely Operated Vehicle was used on a subsequent trip to obtain extraordinary imagery of the two wrecks using powerful underwater lighting. Thus, the facts surrounding Australia’s most enduring maritime mystery could finally be determined. The Kormoran’s bow sits intact on the seabed but most of the ship is gone, scattered in a huge field of debris. It became clear that Sydney had lost her bow, which supported much of what the German seamen had revealed after their capture. It lay resting upside down. About 400 metres away was the main hull sitting upright. Sydney’s bridge, mid-ships section and upper works were severely damaged, and each of her four-gun turrets had received multiple hits by the Germans.

Soon after the wrecks were found, the Chief of Defence Forces appointed a Commission of Inquiry in 2008 to inquire into and report on circumstances surrounding the loss of Sydney and consequent loss of life and related subsequent events. Data and imagery collected by the Find Sydney Foundation were forwarded to the Commission. With much greater powers than earlier inquiries, this Commission ‘aimed to provide an independent, impartial, reasoned and fact-based account’. The Inquiry found that the German survivors told the truth; damage to the vessels confirmed the closeness of the battle; the underwater imagery supported the German’s claim that the early destruction of Sydney’s bridge and control tower most likely resulted in the deaths of many officers, including Captain Burnett, and disrupted her firing; there was fire damage to the whole bridge, correlating the German account that fire made her visible for some hours after the battle; the German version that shell damage and fire made it unlikely that Sydney’s boats would be usable by survivors was confirmed by visible damage to the ships.

By the time the battle had ceased, the 2008 Commission of Inquiry ‘assessed with confidence’ there were many casualties on board HMAS Sydney,

“…probably in the order of 70 per cent…It is, however, probable that there were still some alive on Sydney as she slowly sailed away. They had available to them no lifesaving measures that would allow them to leave the ship, the observed damage pointing to a high degree of probability that all boats and Carley floats that had not been blown overboard during the battle were unserviceable because of shell and fire damage”.

It appears that Captain Joseph Burnett made a grave decision to assess Kormoran as an innocent vessel when she did not appear on Sydney’s plot. The very purpose of maintaining the plot was so ships would know what they may expect to encounter. Burnett should have given more weight to the fact the ship was not expected to be there when making his initial decision. The tragic consequence of not going into action stations, allowing Sydney to sail into a position of disadvantage and great danger by negating her tactical advantages, and giving the opportunity of a surprise attack to the Kormoran, led to the loss of HMAS Sydney and her crew. It is most likely Sydney was overwhelmed at close range in the first five minutes of the battle and then subjected to sustained shellfire for over an hour. In other battles, war ships survived multiple hits from large-calibre shells, or endured torpedo strikes – Sydney suffered both and more. Sydney managed to ultimately destroy her opponent, as damage and fires caused by Sydney’s shelling led the Germans to abandon and blow up their own ship. Sydney’s crew went down fighting without any command structure in place as officers of the ship most likely perished at the first blast the ship received at its bridge and control tower.

One can only assume the torturous anguish suffered by the families of the lost, brave men. One can only begin to feel the pain they suffered to their graves, not knowing the circumstances of their loved ones. Unfortunately, the Royal Australian Navy and the federal government showed callous indifference to the grieving families by refusing to hold any formal inquiry soon after the war ended. To endure the subsequent frauds, theories, and speculations that were allowed to grow and fester over half a century was further insult.

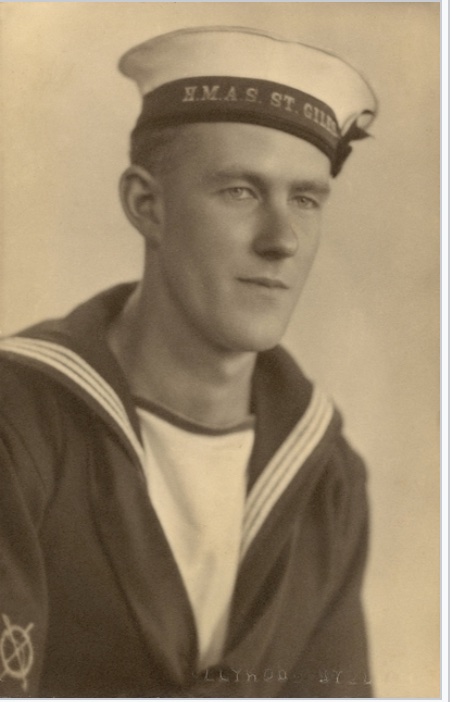

There is another intriguing aspect to this tragic story about an unknown sailor. Nearly three months after the loss of HMAS Sydney, a Carley float, or life raft, was found off Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean, 2500 kilometres from the scene of the battle. The float, which was identified as Australian, contained the body of a white male clad in a boiler suit. Marine growth on the underside of the float suggested it has been in the water for some months. An inquest was held and the body was placed in an unmarked grave on Christmas Island. However, the inquest into the body had not completed before the island was occupied by the Japanese after the Battle of Christmas Island the following month. All records in relation to the inquest and the body were lost or destroyed.

The 1997 Inquiry recommended that attempts be made to find the grave, to exhume the body and acquire DNA for comparison with the next of kin of the crew of Sydney, to determine if the unknown sailor was from the cruiser. A search of the graveyard for the body in 2001 was unsuccessful. A later search in 2006 did, however, manage to find the body. It was in an unusually-shaped coffin, which appeared to have been constructed around it as the body was buried “with legs doubled under at the knee”, the same position it had been in when found on the raft, possibly due to mummification. An autopsy was carried out and the cause of death was identified as “brain trauma caused by a shell fragment of German origin”. Presumably, the sailor was still alive when he got into the raft. Following the autopsy and the taking of samples from the body for identification, the remains of the unknown sailor were reburied in the Commonwealth War Graves section in the Geraldton Cemetery with full military honours on 19 November 2008.

Attempts to extract a DNA profile from the remains began around 2009, although the results were not published before the 2008 Inquiry. By 2014, the identity of the unknown sailor had been narrowed to 50 members of the crew of Sydney. It had previously been reported (2007) that the unknown sailor was most likely one of three engineering officers. In August 2019, it was reported – but not confirmed officially – by media outlets that the unknown sailor most likely to have been buried on Christmas Island was Norman Douglas Foster.

However, in 2021, DNA testing identified the remains as those of Able Seaman Thomas Welsby Clark and the identity was revealed at the Australian War Memorial on 19 November 2021, the 80th anniversary of the battle.

Clark was born on 28 January 1920 and raised in Queensland. He enlisted in the Royal Australian Navy on 23 August 1940 and was trained as a submarine detector in Sydney. Clark joined Sydney‘s crew on 19 August 1941 and was promoted to Able Seaman several days later. He was believed to be the only member of Sydney‘s crew who had been able to reach a life raft after the cruiser sank. He died at sea.

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.”

I have been researching HMAS Sydney for over 28 years. I am an ex-navy veteran. If you want the truth contact email below for further information.