I dedicate this blog to the memory of Lana Syme (1939-2021), who visited and stayed at her aunt’s place near Olinda in her youth. Lana loved the area and, with husband Bill, settled in Olinda 35 years ago.

Nearly one hundred years ago, small sawmill settlements were located within tall productive forests in the central highlands. On one fateful day in 1939, they were decimated by bushfires and never returned. In a beautiful mountain area not far from Melbourne’s CBD, people have lived literally underneath the world’s tallest flowering trees for the last one hundred years. The small settlements dotted in and around the Dandenong Ranges have persisted and avoided the calamity faced by the sawmill townships. They are, however, not immune to fires. There have been many since early European settlement. Under the right conditions a bushfire could wipe out the forests and settlements on the Dandenong Ranges in a day. So why do people still live there and could they be saved from such a tragedy?

“The fires have brought a new beauty to the picturesque Dandenongs. Acres of charred grass land form a vivid patchwork with the green of the fern gullies and scorched gum trees bear a foliage of rich russet”.[1]

While we were in Melbourne early in the year, we spent a bit of time in the Dandenong Ranges at Olinda, visiting my wife’s parents. I have always been fascinated by the Dandenong Ranges because people live in the forest surrounded by the world’s tallest hardwoods, the mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans). These forests support a dense understory of ferns (Dicksonia antarctica and Cyathea australis), dogwood (Cassinia aculeata), wattles (Acacia app) and musk (Olearia argophylla), and a tangle of small shrubs with fallen timber lying in all directions. Not a place you would typically create a manicured garden. And yet as you drive through the Ranges, there is a blend of cultivated gardens, much like the gardens designed by Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown in England. Today, the Dandenong Ranges support a random location of narrow gravel roads, houses, and stately gardens underneath the towering forests. Unfortunately, they sit within one of the most fire-prone areas, marked by a history of severe bushfires. Ever since settlement on the Ranges, fires have been a constant menace. They repeatedly destroyed sawmills, farms, villages, and houses. And unfortunately lives have been lost. But that hasn’t deterred the area from being developed into a residential and weekend getaway for the city’s discerning folk, who see the hills as a relaxing and peaceful refuge.

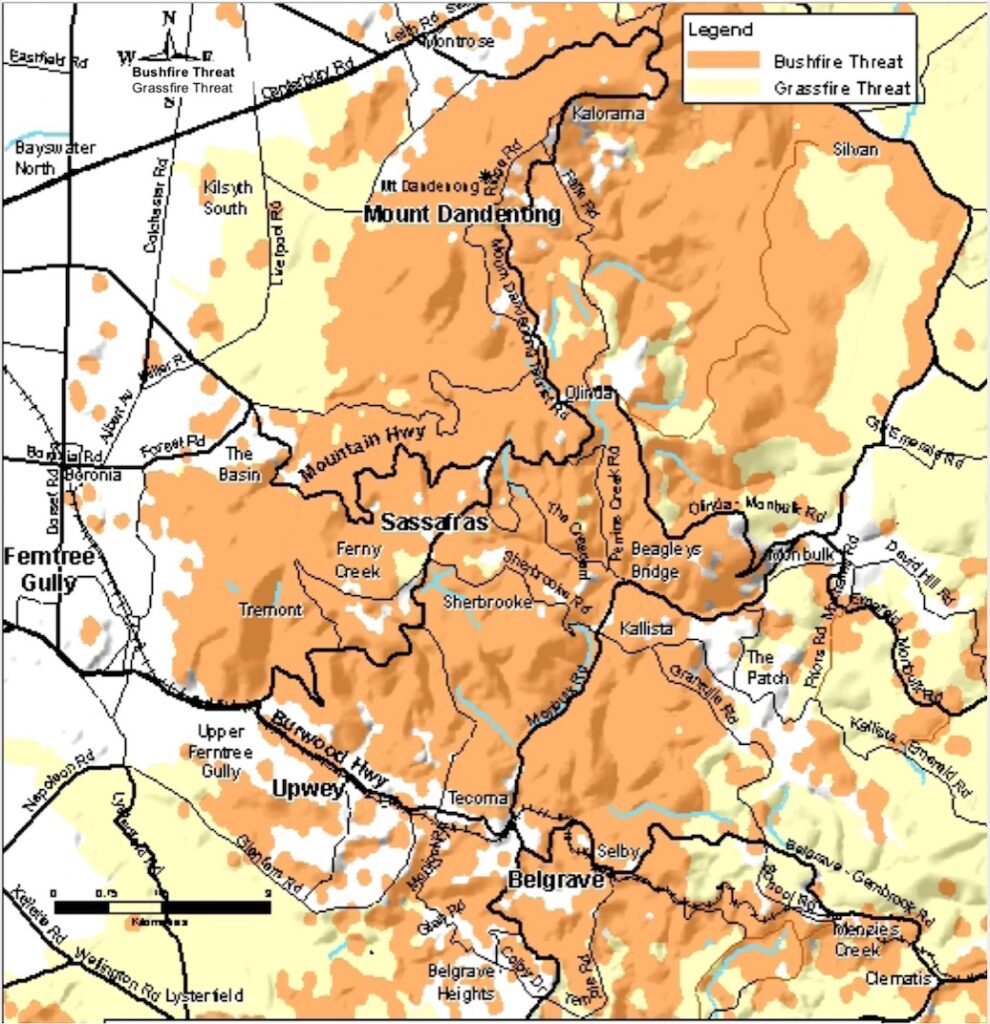

The township of Olinda sits towards the top of the ranges, and my in-laws live on the sheltered eastern slope just to the east of Olinda above Kallista and Monbulk. Sections of this slope support towering mountain ash forest that has not been affected by previous disasters such as the 1939 Black Friday and 1983 Ash Wednesday fires. I researched the settlement history to make sense of today’s patterns, mainly from the plain on the western side rising through Ferntree Gully, The Basin, and up through Ferny Creek, Sherbrooke, Kallista, Sassafras, Olinda and onto Mount Dandenong. The biggest fire threat to the Dandenong Ranges are days of high temperature, low humidity and strong hot and dry winds from the north-west to the south-west. The forests exposed to these conditions on the western slopes are drier, more open, and prone to frequent fires. Under extreme fire weather conditions, a fire can race up these slopes and reach the top of the ranges. Fires that start in The Basin on the western foothills generally follow two patterns. Either straight up over One Tree into the Dandenong Ranges National Park and onto Upwey. The other path is the back of Sassafras township and towards Olinda.

Settlement history

Daniel Bunce, a botanist from Tasmania, was probably the first explorer to seriously travel over the whole Range. Between 1839 and 1842, on many trips, he walked through the forests and ferns. Baron Ferdinand von Mueller became Victoria’s Government Botanist in 1853 and immediately set out for the Dandenong Ranges, as it was seen as an interesting botanical landmark. He visited the hills many times, and in the 1870s, set up a semi-permanent camp at The Basin to aid his studies of the area.

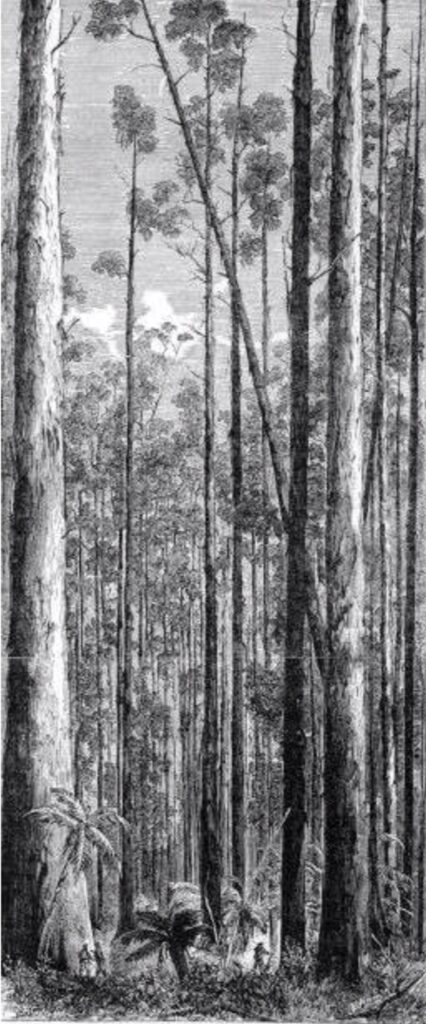

Settlement followed on the foothills as farmers tried to start farming on the foothills. The first Dandenong settler, the Reverend Mr Clow, called his cattle run after the mountain at the head of Dandenong Creek – Mount Corhanwarrabul.[2] The forests on the Ranges, including the wet mountain ash, were more open than today. While they supported tree ferns, you could still ride a horse through the forest (see the drawing below). Timber getters soon followed as they sought the vast timber resource. A sawmill was set up near Upper Ferntree Gully and a timber camp was established by George Holden and his two sons Mark and Luke. They worked in the forests around Olinda for nearly 50 years, starting in the early days around the early 1850s. Under a forest licence, they felled the giant mountain ash trees and split them into palings.

Pastoral runs were established on the lower slopes near Fern Tree Gully in the 1850s and 60s. More settlers came to the area when gold was discovered near Emerald in 1858. George Dodd and his sons cleared land and established fruit orchards and nurseries in the rich soil. The first ordered settlement took place in the early 1870s when land on the Range’s western slopes was divided into 100-acre allotments.

Mt Dandenong, Sassafras and Olinda are beautiful villages located on or near the top of the ranges. They were established in the mid-1890s after the Settlement of Lands Act 1893 authorised the opening of portions of land in the area for settlement. John McIntyre, Minister of Lands, ‘threw the hills open for selection in an endeavour to encourage unemployed city dwellers to settle the land’.[3] This was the government’s response to the dreadful depression that gripped the country in the wake of the ‘Marvellous Melbourne’ gold boom that eventually busted. The financial collapse left tens of thousands destitute, with very little hope. Many city-dwellers migrated to the Ranges when they found hard times during the 1890s depression. Free selectors chose 10-acre blocks for clearing. Village settlements were formed after approximately 6,500 acres of land was excised from state forests. Most of the allotments were at Mt Evelyn, Mt Dandenong, Kalorama, Ferny Creek, Olinda, Sassafras, Sherbrooke, Kallista and Monbulk.

The settlers were assigned densely forested lots which had to be cleared. They ring-barked and felled forest trees. Most planted berries and other fruits and sold them at the Victorian Markets during the season as they were not experienced farmers. They lived in timber shacks on their blocks. Prices for berries soon declined, and within two decades, the blocks were deserted. In the 1920s, the denuded land was sold to city dwellers who wanted acres with a view.

Tourism became a popular money-making business in the area. Guest houses were erected to host tourists. Olinda’s most significant advantage was during the winter months when there were occasional snowfalls. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, Olinda was a popular resort for day tourists and holidaymakers. ‘Lorna Doone’ was built as a guest house in the early years of the twentieth century and had all the world elegance of past days. Development increased after World War II when building restrictions were eased. Many fine homes were built in the Coonara area. Famous artists called Olinda home, including Eugene von Guerard, Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts, Max Meldrum, Ray Whiting, Peg Maltby, and Mary Card. All around the homes of these new settlers, the forest grew back.

Because the Ranges were popular with Melbourne day-trippers from the 1870s onwards, many areas were protected as parklands. This settlement pattern and history have culminated in the Dandenong Ranges having clusters of small and medium lots that interface with a national park; settlements that are dispersed throughout vegetated areas, both at the edge of and between national parks; and single access roads servicing the residential properties. The Dandenong Ranges, particularly on the western and southern slopes, are the highest risk environments to bushfire during summer. This type of settlement and infrastructure and their location, combined with a mountainous terrain, highly flammable vegetation and climatic patterns, make the Dandenong Ranges one of the most bushfire prone regions in the world. The townships, hamlets and surrounds on the southern side of the Dandenong Ranges are very high-risk areas.

A brief fire history

Below is a summary of the known fires on the Ranges. It is not exhaustive, nor does it cover every known fire that has been associated with the Ranges. It does, however, include all significant fires that have been recorded on the sheltered eastern and southern slopes of the Dandenong Ranges below Olinda, south towards Kallista.

There was little coverage of fires before the early 1850s. The infamous 1851 fires burnt nearly five million hectares across Victoria, including the Dandenong Ranges, but specific details are scant other than ‘the whole mountain burnt’.[4] One newspaper reported ‘the glare from the burning bush around Dandenong [could be seen from Melbourne], the whole of that portion of the country being in flames’.[5]

In January 1870, a large fire burnt under a north-westerly wind, affecting a large area of timber. Details about exactly where the fire occurred are limited, but it is believed to have passed through One Tree Hill.

I read a brief reference to fires at The Basin and Olinda in 1880, but I could not find any newspaper records or other references to this event. December 1880 and January 1881 were scorching months in Melbourne, and there were many fires elsewhere in the state.

After early settlement, the first recorded fire was through the careless burning of cleared scrub near Fern Tree Gully in 1893. A year later, another fire under similar circumstances burnt a property at Sassafras, as did several fires in 1895 and 1896.

In early February 1898, the new selectors on large areas of the Ranges had their allotments burnt. They included Ferny Creek, Kallista and Sassafras. Bushfires stretched from Wandin to Monbulk.

Early in 1902, warm, dry conditions spread bushfires in the northern parts of the Dandenong Ranges, particularly around Mt Dandenong.

There were fires to the east and south of Olinda in January 1905. The fires started on the mountain’s face from ‘Hazeldell’ and burnt out Mrs Leake’s property a half a mile from the township.[6] The diary of Mrs Janet Dobson, from The Basin, provides a detailed record of this fire.[7] The fires started near One Tree Hill on 31 December 1904. The hot, dry weather continued, and on 11 January, the heat, fanned by strong north-westerly winds, ‘was almost unbearable with fires raging all day’. There was a big fire around ‘Hazeldell’ and right to the top of the ranges. On 14 January, the fire went over the mountains and burnt down houses before a cool change that night, and rain for two to three hours the following morning, put the fire out.

On Boxing Day in 1907, there was a fire under the influence of a strong north wind at Upper Fern Tree Gully. It was believed to be caused by the careless throwing away of matches by smokers after lighting their pipes. It burnt the whole National Park and created a ‘blackened mass of burnt scrub and grass’.[8] Large tree ferns were also badly scorched.

Fires started near Mount Dandenong on 25 April 1910. Strong north-westerly winds fanned the fire and threatened the village settlement on the easterly slope of Mount Observatory. A storm two days later with heavy rainfall put the fire out.[9]

In 1913 one of the worst fires swept through Sassafras and Monbulk. One fire broke out in the drier forests near Mt Dandenong settlement on 4 February under hot north-westerly winds and travelled in a south-easterly direction. Another fire started near Ferny Creek. Both fires combined, and Monbulk was directly hit, with the new primary school and recently built Mechanics Institute burnt down. A total of 80 buildings were destroyed, including 26 in Monbulk. A few houses were burnt at Olinda.[10]

One of the most disastrous bush fires known in the district occurred on Sunday, 25 October 1914. Six dwellings were destroyed. The fires were prevalent between The Basin on both sides of the Olinda Road. Hot northerly winds on Saturday, 24 October, fanned the smouldering fire into flames enveloping the mountain. It spread in three directions sweeping southerly down the valley behind Dewrang, north-easterly towards the Mechanics and easterly past Olinda down the mountain threatening ‘Lorna Doone’. The beautiful Sassafras Gully burnt on one side and Sherbrooke on the other. Mernda heights burnt, and then it descended to Kallista and back towards Belgrave. Tall trees held a crown fire. The hills for miles around were alight. Dodd’s Olinda coach and three horses were affected. ‘The driver had to abandon his team as they sank to the ground, overcome by the smoke and heat. Soon afterwards, the horses rallied and madly took the descent with the blazing coach behind them.’ Roads were blocked with fallen timber. Hundreds of trees lay felled by the fire.[11]

In January 1919, there were reports of a ‘raging’ bushfire that started in the grass and scrub country near Mount Dandenong and spread into forested sections near Olinda. The Olinda Hotel and other buildings were under threat but escaped damage.

There were fires again in the summer of 1920. The previous summer months had been exceptionally dry, and the timber in the forests quickly ignited when lit.[12] In February, a bushfire was burning for two weeks in the ranges near Monbulk and a ‘few miles’ from Olinda. The surrounding district was enveloped in smoke. The fire threatened Sassafras and within a mile of Olinda.[13]

Church services on Sunday 12 February 1922 were shortened when the fire alarm rang out in Upwey. A strong northerly wind fanned the fire through the timbered country and headed towards Belgrave after a wind change.

Havoc was caused by a fire in late February 1923, especially on the south-eastern slopes between Sherbrooke Falls and Fern Tree Gully. On Tuesday, 20 February, the fire broke out near Tremont about two miles above Fern Tree Gully. It began on the side of the hill close to a bungalow. It moved south and burnt all night, racing up the mountain through the dry fuels. It had nearly reached the summit by Wednesday morning and worked its way down the western slope by dusk. On Thursday morning, it took a new line almost up to the Sassafras Road. Another outbreak started on the ridge separating Sherbrooke and Ferny Creeks above the Sherbrooke Falls in dense scrub and bracken, just below the Upwey tourist track to the falls. The fire raced up the hill towards Ferny Creek. Houses were saved, and only fences and sheds damaged. The forester in charge of the district and his small workforce worked hard to cut a track ahead of the flames as they feared if the fire turned back, Sherbrooke Falls, Jacobs Ladder and the Fern Bower would be destroyed. They were credited with saving the townships of Belgrave, Sherbrooke and South Sassafras.[14] There was concern on the mountain regarding how weekenders allowed the grass, bracken and blackberries to accumulate on their properties ‘which is a menace to the whole district and is courting disaster’.[15]

After a dry period in late October 1925, several isolated scrub fires near Olinda spread into uninhabited forest country and quickly headed towards Sassafras and Silvan. Fortunately, the fire was confined to the forest areas. There were ‘huge clouds of dense smoke rolling over the range from Silvan, to the accompaniment of the angry roar of flames and crackling of dry timber was the first warning of the fire’.[16]

On Sunday, 31 January 1926, it was reported that the Ranges were ablaze from end to end. Aura, Monbulk, Sassafras, Ferntree Gully and Clematis were surrounded by ‘walls of fire’. The fires didn’t reach the top of the Range, and the beauty spots were not affected, although they were travelling near Upwey and Ferntree Gully. On Black Sunday, 14 February 1926, winds reached 97 kilometres per hour and small fires burning on Mount Donna Buang came together and spread quickly to the Dandenong Ranges. Also, many fires broke out in the bush at Monbulk. The worst hit was Mt Evelyn, Lilydale, Packenham and Emerald on the Range’s lower foothills. It was reported they swept across The Patch and through the hills into Selby. The 1926 fires led to the formation of The Basin and Olinda Bush Fire Brigades the following year.

A severe fire occurred in January 1928 at The Basin. Six houses were destroyed as a strong northerly wind fanned the fire, which raced through heavily timbered country towards the settlement. Most of the homes at the Basin were, at that time, only occupied on weekends or during holiday periods. ‘In a few moments the tiny spurt of flame had developed fearfully into a mighty conflagration…the fire roared its destructive way through dense undergrowth, scrub and forest…’[17]

In late January 1929, bushfires swept up the Mt Dandenong slopes from Montrose and nearly reached the Kalorama township.

‘Red Tuesday’ on 19 January 1932 saw many fires ‘in almost every part of the State’. It was a day of hot north winds, high temperatures and low humidity. In the Dandenong Ranges, there was a fire close to Olinda and Sassafras. About 100 fire-fighters, mainly local residents, managed to bring the fire under control after a few hours of strenuous work. Many houses were under threat, and some residents hurriedly removed their possessions and furniture to the roadside. The previous night there were reports of many fires in the Ranges. Montrose, in particular, was under threat and on the following Saturday evening the fire ‘tore down the hillside’ from Mount Dandenong, fanned by a high wind.[18] Many acres of forest was burnt in the fires and several weekend homes destroyed.

In October 1933, fires burnt several areas, including Sherbrooke forest, until a cool change eased the threat.

In early autumn 1934, there was a period of hot, dry weather with temperatures in the late 30s for five consecutive days with strong northerly winds. Fires started daily in the Ranges. The first fire was at Tecoma. Another at Upwey, from a burn off by a railway gang, roared down the valley. Another fire started in the National Park at Upper Fern Tree Gully and headed towards Devils Elbow. Not long after, another fire started at Tremont. Around 300 fire-fighters battled the blazes in an effort to protect houses. Remarkably only two houses were burnt down.

On 1 April 1936, fires were everywhere and worst in the Dandenong Ranges under blustering northerly winds. A newspaper reported the ‘Dandenong mountains for the greater part of the night resembled a blazing inferno and the fire-fighters were out all night’.[19] The fires burnt the hills and gullies adjoining the main road from Belgrave to Selby and the heavily timbered country between Olinda and the Silvan Dam.

On 28 November 1937, a fire threatened houses at The Basin. It ‘roared’ up a natural funnel through forest with a thick understorey.

A strong south-easterly wind and intense heat fanned a blaze near Upwey, covering hundreds of acres on 19 January 1938. The fire started at The Basin, and several houses were under threat before the fire was brought under control. A week later, another outbreak in scrubby country between Upper Fern Tree Gully and Upwey was quickly contained by fire-fighters.

On 9 January 1939, a fire was mainly confined to the lower western slopes of the Ranges. The fires of ‘Black Friday’ were fanned by a hot northerly wind blowing at a steady 60 kilometres per hour with a temperature over 40OC and very low humidity. Numerous fires burnt around the state and destroyed 1,500 homes and at least 66 people died. Monbulk, hit hard by the fires of 1913 and 1926, was again threatened, with houses on the outskirts destroyed.

Fires smouldering on private property flared up and burnt areas near Olinda and Monbulk on 17 March 1940.

Fires threatened several townships in a triangle bounded by Ferntree Gully, Monbulk and Pakenham on Saturday 22 January 1944. It was a scorching hot, windy day. A fire started in dense uninhabited forest country near The Basin and quickly burnt to Ferntree Gully, then to the lookout, and into the national park. Fortunately, rain in the late afternoon helped bring the fires under control. In late February, there was a fire in the Sherbrooke forest that headed towards Belgrave. In late March, there were more fires at Tecoma and between Kallista and The Patch.

Driven by fierce northerly winds, there were many fires on 22 March 1945, probably due to carelessness. One of the fires started at One Tree Hill and quickly burnt up into the forests. Another near Monbulk was believed to have started from burning logs.

One house was destroyed in a fire that threatened Kalorama over six hours in March 1951.

There were a series of small fires in late 1954. Near Fern Tree Gully, a small fire in the forest, which began near One Tree Hill, burnt to within 200 metres of the lookout. In November, there was a fire in dense forest two miles from Olinda, which was quickly brought under control.

Following a dry spell over three weeks, a fire fanned by strong north-westerly winds quickly burnt the forest between Sassafras and Ferny Creek on 13 April 1959.

In January 1960, there were bushfires at The Basin, which threatened Sassafras and Olinda.

One hot summer day in 1962, arising on the western face of the mountain among the dry forest, came a fireball. ‘Black Sunday’ 14 January 1962 was a hot, dry summer day with northerlies gusting strongly and temperatures heading towards 38OC and low humidity. It was one of the worst fire days in the Ranges. A spark from a domestic incinerator at The Basin was the catalyst and quickly raced up the steep slope of Mount Dandenong. The fires swept up the Range and along the ridge between Mt Dandenong and Sassafras. Within hours the mountain was ablaze. A wind change in the afternoon saw the fire take off to the north-east toward Olinda. Monday 15 January saw the fires still out of control. More than 46 houses in the Olinda-Sassafras area were destroyed. Olinda township was threatened, and the population evacuated to the golf course. On three sides, the fire attacked the township. Under the influence of a strong southerly sea breeze, the fire moved north towards Montrose. The fire crowned along the ridge in the Ferntree Gully National Park and spawned spot fires. Tuesday was another hot day with temperatures nearly 40OC, and Upper and Lower Ferntree Gully on the Ranges’ southern side were under threat. A late wind change turned the fire back to the north-east, and late in the afternoon, a firestorm of dramatic proportions developed in the Ferntree Gully National Park near the Devils Elbow. Towards evening the fire was burnt east of Olinda and Sassafras and threatened Kallista. Evening rain allowed the fires to be contained.[20] The fires caused an eerie red glow in the night sky. Much of the Dandenong Ranges between The Basin and Mount Evelyn was blacked out.[21]

Fire again hit the Ranges in 1968. On Monday 19 February, a significant fire had developed on the hill above The Basin. It quickly moved up the western slopes of Ferntree Gully National Park to One Tree Hill through Tremont and into the back of Upwey, destroying 65 homes. After these fires, the Parks Service, Forestry and CFA were directed to develop a fire protection and prevention plan for the whole Ferntree Gully National Park.

It is believed an arsonist was responsible for a fire in the National Park which reached the former One Tree Hill lookout in December 1972.

Three fires were lit within minutes by an arsonist at The Basin in March 1974. More than 60 spot fires were reported that month in the Dandenong Ranges, and authorities were involved in an intensive hunt for the arsonist or arsonists.

In March 1980, a large area of the Doongalla State forest burnt over three days. There were also fires reported at Ferntree Gully National Park, Upwey and Mt Dandenong.

The 1983 ‘Ash Wednesday’ fires, which began at Belgrave Heights, spread heavily through the populated areas at the base of the Ranges. By 5:30 pm, it was reported there was no longer any danger in the Belgrave area and the focus shifted to stopping the fire at Officer. By 6:30 pm, however, under a gusting easterly wind, the fire developed a long and treacherous eastern flank. Spot fires appeared in the gullies closer to Upper Beaconsfield and sparks and embers, under a strengthening wind, shot over Upper Beaconsfield into the Toomuc Valley, the wooded corridor between Officer and Cockatoo. Searing winds, gusting to cyclonic force, began to ‘corkscrew’ from the south-west about 8 pm. The fire reached Cockatoo, 9km to the north-east within minutes, destroying houses near the Cockatoo Valley’s lip. The whole valley was on fire. This devastation was repeated at Selby, Upper Beaconsfield and Emerald. The ‘Ash Wednesday’ fires did not affect the main ridge of the Dandenong Ranges, but the effect on Sherbrooke’s whole Shire was widespread. It was reported that the ‘once picturesque Dandenong Ranges…resembled charred battlefields’.[22] It was a day of hell on the southern and eastern foothills of the Dandenong Ranges.

The 21 January 1997 was a hot summer’s day with a strong northerly blowing. Around midday, a number of fires started in the Montrose area. Shortly after, more fires started in The Basin and two near Fern Tree Gully. The Basin fire ran its typical course towards Ferny Creek and destroyed several houses, and two people sheltering in their homes were killed. It was estimated that the fire raced up the hill in a very short time. The two other fires merged in the Ferntree Gully National Park and headed towards Upwey. Bulldozers were called in to construct breaks to prevent the spread of the fire to the west. Aerial water bombing was also employed. Around 6:00 pm, there was a strong south-westerly wind change. The fires were contained later that evening but not before 41 homes were destroyed and three people killed.

‘Black Saturday’ 7 February 2009 saw approximately 400 fires across Victoria. The Dandenong Ranges, on the whole, were not affected on this disastrous fire day. However, there were two significant fires at Upper Ferntree Gully and Upwey, where seven houses were destroyed.

Living with fires

In the quarter of a century after WWI, Victoria, in general, experienced intense bushfires every fifth, sixth, or seventh year. No other state matched Victoria’s casualties during the fires in 1926, 1932, 1939 and 1943-44. The main reason for the high death toll during that period was that people lived in the forest. Sawmills and people and their settlements penetrated deeper into the tall forests to the east and north-east of Melbourne. Holiday houses and retreats were built in the leafy Dandenongs bush, not far from Melbourne. They replaced the sawmilling camp and small farms as the places most vulnerable to fatal bushfires.

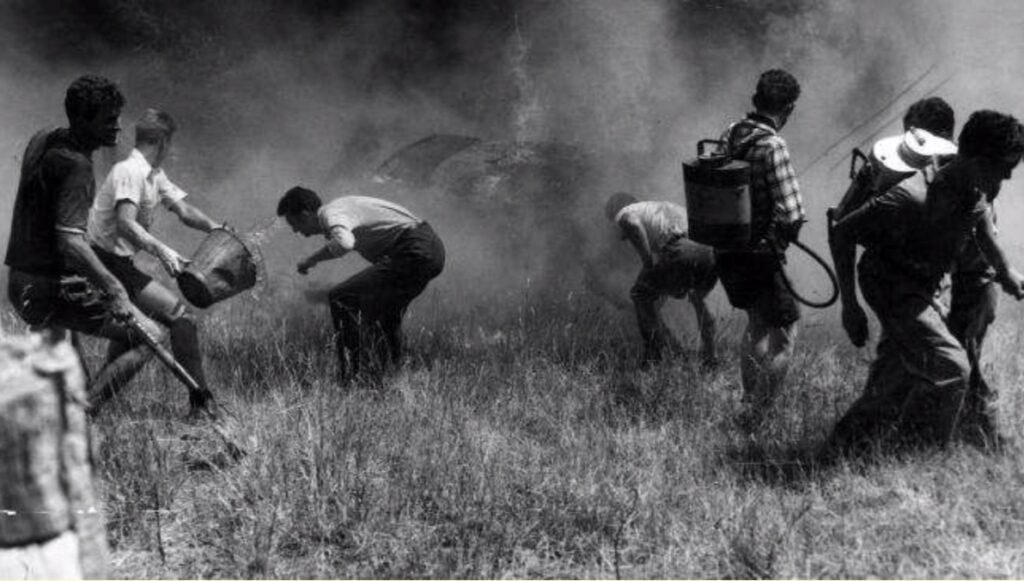

The other reason for the high number of deaths was up until just prior to World War II, fire management across the state was practically non-existent. In late spring and early summer, fires were deliberately lit for a variety of purposes. They started as mild running or smouldering fires, and if the summer was hot and dry, they would form infernos and inflict losses on the settlers and townsfolk. Up until the 1939 Royal Commission, no-one contemplated how they could reduce or eliminate the property damage and protect lives. No-one asked the simple question – what were the causes of the fires, and how can we stop their spread?

The history of damaging fires in the Dandenong Ranges shows that there were fires most seasons until the 1940s. This reflected the carefree attitude towards fire and its damaging effects by early settlers looking to clear away the impediments so they could live within the forest. For decades the leading cause of bushfires in the Ranges was burn-offs getting out of control. Settlers used to either light fires in summer to burn heaps of cleared scrub, or burn rubbish in an outdoor incinerator, and no efforts were made to extinguish the fire. When hot days with strong winds arrived, the burnt or burning areas quickly spread to nearby unburnt areas. After early settlement, the first recorded fire was through the careless burning of cleared scrub near Sassafras in 1893. In his Report of the Royal Commission into the 1939 fires, Judge Leonard Stretton was very critical of the ‘anarchic use of fire’ by forest fringe settlers and forest users, such as settlers, miners and graziers. Their fires were deliberate, and they were not compelled to prevent the spread of their fires. While legislation was in place to restrict the lighting of fires during summer, they were mainly aimed at close distances to various crops and came into force when holdings were large and settlement sparse.

Settlement and unregulated timber harvesting affected the original forests. The slopes of the Dandenong Ranges became more susceptible to fires as trees and forests were cleared and opened up for settlement. The magnificent Sherbrooke forest at the south-eastern base of the Range was exploited for its timber in an unregulated way and was almost completely cut out by the late 1890s. The same happened on the foothills on the western slopes and the top of the Range around Olinda. The fires up to and including 1926, led to the establishment of regrowth that regenerated the foothill slopes at Sherbrooke and resulted in the magnificent forest we see today. It is a similar story for the sheltered eastern slopes below Olinda.

But it was not only the settlers that created problems. There was neglect by many of the owners of weekenders of holiday homes who allowed their blocks to be overgrown with regrowth and weeds. The situation was eloquently summed up in 1934:

“The neglect of weekend block owners to clear their blocks of undergrowth in a season like the present amounts to almost criminal negligence. Local residents who give their time and labor without recompense to fight fires are forced to endanger their lives through this neglect. In many cases the undergrowth is permitted to reach right up to the dwellings, and in many instances highly inflammable bracken and other debris is lying against the walls of the houses”.[23]

One place that became notorious was the drier western foothills at The Basin. The Basin is situated in a depression in the hills on the western slopes of the Dandenong Ranges. It is surrounded by very dense forest.

Once such resident summed up the fire threat thus:

“The Basin is actually a fuse leading to the powder barrel of the Dandenongs. Once the fuse is lit the path of the fire is easily predicted. It goes up to One Tree Hill, plunges down into Ferntree Gully National Park, and send its lashing tongues everywhere, towards Sassafras, Ferny Creek, Upper Ferntree Gully, Upwey and further, its main direction depending upon the prevailing wind.”[24]

After the devastating 1968 fire which started at The Basin, one writer to the newspaper advocated that the settlement should be ‘liquidated completely and for good’. There was an official buy-back scheme for the Dandenong Ranges initiated after the 1962 fires. The strategy focused on areas that had been subdivided in the 1950s and identified as high fire risk on the steep western slopes above The Basin. It was a controversial scheme as there was a mixture of voluntary and targeted acquisitions. By 1968, however, the scheme had almost ceased due to a lack of funds. There was a lot of progress on the northern areas in the old New Mystic Lake Estate that is now part of the National park’s fire buffer zone. The fire protection of the purchased lands returned to public ownership. Private allotments were gradually consolidated, thus reducing fragmentation of the residential interface with public land. The program ran until about 1984.[25]

After 1939, it was recognised that a more coordinated, whole-of-state approach to fire management was needed. Judge Stretton presided over the Royal Commission, and he ‘sought a new codification of fire practices, not their abolition’.[26] It eventually led to new ideas in the prevention and control of bushfires based on programmed burning, rapid response to fire outbreaks, improved surveillance, and the use of aircraft. The passing of the Bushfires Brigades Bill in 1934 led to definite action to be taken to compel the clearance of blocks.

Since settlement, the way fires behave in the Sassafras-Ferny Creek area is relatively predictable. They usually travel from the foothills below. Typically, the fires that race up the slopes are short-run events. Major outbreaks have burned uncontrolled for several days, such as the 1962 fires, or more than 24 hours like the 1968 fires. Fortunately, most fires were contained within a matter of hours, just like the 1997 fire. The major difference between the 1997 fire and those in the past was that it claimed lives in addition to destroying bush and property. Bushfires have occurred as early as October and as late as April. The risk of bushfires is greatest when there has been a prolonged dry period or drought the preceding summer. There is evidence that El Nino years are often associated with acute fire danger. The most dangerous period has usually been late January to mid-February, when the forest fuels have dried sufficiently combined with strong dry winds and hot days with very low relative humidity.

Fire plays a significant role in the regeneration of forests. Rather than being seen as a destructive force, nature utilises fires to rejuvenate the mountain ash forest. The right conditions are required to reset the forest, with typically wet fuels dried out after sustained drought conditions and a source of ignition. That is why mountain ash can grow so large, because, in nature, the combination of dry fuels and ignition are rare, and fire is an infrequent visitor.[27]

Conclusion

What is not appreciated by the urban-dwelling public and mainstream media is that the magnificent mountain ash forests we see today on the Dandenong Ranges are not pristine remnant forests that were present before European settlement and saved from development or clearing. They arose from severe fires after widespread clearing and settlement.

European settlement changed this balance in many ways. First, fuel wasn’t removed – it was rearranged. Settlers re-ordered and changed the fuel by clearing the native understorey to accommodate habitation. Secondly, the ignition of fires became prevalent. The re-ordered fuel needed to be dealt with, and the easiest and most convenient way was to burn it.

Stretton recommended a single fire-fighting authority to deal with the prevention and spread of fires. The Forests Act 1939 enabled the Forests Commission to take complete control of fire suppression and prevention work on public land in Victoria. There was no longer confusion over who should be in charge of overall fire management between the Forests Commission and the Board of Works. By 1944, the Country Fire Authority was established to manage the rural bushfire brigades and were responsible for protecting all areas except for Crown land. This closer and organised management of fires, combined with broader powers to control the lighting and suppression of fires, has gradually reduced wildfires in the Ranges. However, a new threat has emerged. Since the 1970s, every major fire in the area has been the result of arson, as dry lightning storms are unusual, and lightning strikes are less common. But they have been less common, even though the fuels in the wet forests have continued to build up.

Despite frequent fires in the more susceptible forests of the Dandenong Ranges, Olinda hasn’t seen a significant fire since 1962. Olinda is located at one of the highest points on the Range, and in winter, when snow falls, it is thickest at Olinda. It is not only because of the elevation but because it is uniquely sheltered from particular winds. Unfortunately, in the wetter, sheltered forests, there is no place for controlled fires. One thing is for sure there will be a fire, but not a fire we want. I am trying to understand whether the mosaic of European gardens interspersed with the traditional fine fuels in the understorey may play a role in reducing fire intensity when there is a fire on a severe fire weather day.

I am interested in other experienced fire practitioners’ views on what sort of fire would ravage that part of the Dandenongs – do you think the mosaic of deciduous gardens will help lessen its impact?

[1] ‘Charred acres in the Ranges’ The Herald, Friday 3 April 1936, page 16

[2] When looking up at the Dandenongs from Melbourne you see two softly curved mounds of Mount Dandenong and Mt Corhanwarrabul

[3] Coulson, H. (1968) Story of the Dandenongs 1838-1958. F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne, page 352

[4] ‘History’ Olinda Rural Fire Brigade https://olindacfa.info/67-2/

[5] The Argus, 10 February 1851, page 2

[6] ‘The Bush Fires’ The Argus, Saturday 14 January 1905, page 16

[7] Coxhill, R (1992) Fire on the hill – flowers in the valley. Chapter 8 The Basin Fire Brigade. Available online http://www.coxhill.com/basinhistory/bookview.htm

[8] ‘Fern Tree Gully damaged’ The Age, Saturday 28 December 1907, page 9; ‘Fern Tree Gully fire’ The Age, Monday 30 December 1907, page 5

[9] ‘Mount Dandenong outbreaks’ The Age, Wednesday 27 April 1910, page 8

[10] ‘Destructive bush fires’ The Weekly Times, Saturday 8 March, page 39 – a letter by Norman Jones 11 years old to his Uncle Ben

[11] ‘The Heat Wave’ The Argus Monday 26 October 1914, page 8

[12] ‘Bush Fires’ The Argus, Thursday 26 February 1920, page 4

[13] ‘Bush fires near Melbourne’ The Ballarat Star, Monday 8 March 1920, page 1

[14] ‘The Argus’ Thursday 22 February 1923, page 7; ‘Flames seen over tree-tops’ The Argus Monday 26 February 1923, page 7. South Sassafras is now known as Kallista.

[15] ‘Olinda’ The Reporter, Friday 2 March 1923, page 5

[16] ‘Extensive bush fires’ The Age, Thursday 29 October 1925, page 11

[17] ‘The bush fires’ The Age, Thursday 12 January 1928, page 9

[18] ‘Big fires in the Dandenongs’ The Herald, Monday 18 January 1932, page 1

[19] ‘Settlement destroyed by bushfire’ Lismore Northern Star, Thursday 2 August 1936, page 7

[20] My mother-in-law’s aunty Amy lived at a property called ‘Wylah’ near Olinda on the Belgrave-Olinda Road (formerly Upper Coonara Rd). She lived in Melbourne and owned the house as a retreat in the mountains. To the north-east of the house was a tank on a wooden stand and outbuildings nearby. The tank stand and outbuildings burnt down in the fire and the tank toppled tipping water over the house, saving it from the fire.

[21] ‘Suburbs in peril as deadly bushfires shocked Melbourne in 1962’ Herald Sun, 12 January 2017 (by Jamie Duncan)

[22] ‘The Wednesday two states burnt to ashes’ The Bulletin 11 March 1983, page 20. In the Dandenong Ranges, tragically 12 volunteer firefighters were trapped by a ring of fire and died by their trucks.

[23] ‘Bush fires’ The Age, Wednesday 14 March 1934, page 10

[24] ‘Urges drastic act against The Basin’ Knox News, Wednesday 13 March 1968

[25] McHugh, P. (2020) Forests and Bushfire history of Victoria – a compilation of short stories. Story 82 ‘Buying back the farm’ page 322

[26] Stephen, J. Pyne (1991) Burning Bush: a fire history of Australia. University of Washington Press

[27] In 1891, Howitt noted that South Gippsland had two age-classes of thick young E. regnans forests with dense shrubby understoreys, where there had formerly been very open forests occupied by Aborigines. There is real conjecture about the structure of these tall ’wet’ forests prior to European settlement. Early paintings depict them as we see them today – tall forests with a dense cover of mesic understorey species, such as tree ferns. Yet we know from early explorers such as Howitt, that E. regnans were named blackbutt because the basal stocking of rough bark was blackened by mild fires. For a more detailed discussion on this topic see Vic Jurskis’ opinion piece at: https://quadrant.org.au/opinion/doomed-planet/2021/04/empirical-evidence-vs-ecological-modelling/?fbclid=IwAR3BRK17j_3XF9fdzHRBxR00XrLzrXASujncHB57Ox7lBCWO9QsAXHMHyCU

Well researched and written! Would like to see a hard copy book. It would accompany “Ordeal by fire” magnificently!

Ex Forests Commission et al

What an amazing article! I live in Ferny Creek at present and am very concerned about the fire risk.

I was googling to see if I could find the names of the people killed at One Tree Hill in the January 1997 fires.

Could you contact me to discuss publishing your research either in the Hills Community Focus Magazine and / or as a separate publication.

We are working to develop a Township Group / Community Association for Sassafras, Ferny Creek and Tremont to build community cohesion, support community initiatives and address the issues currently faced in the area. We are holding an Open Meeting on Monday 25th March at 7.00pm at Sassafras Hall.

I know you don’t you live locally – but it would be great to discuss a publication – people here don’t want to realise the danger – they are safer if they informed and your article does this amazingly well.

I would like to see what the possibilities are.

Best regards

Liz Millman Secretary: Hills Creative Alliance