Many Australians see tropical cyclones as a northern phenomenon — storms that belong to Cairns, Townsville, or the Kimberley. Yet, the Fraser Coast, stretching from Fraser Island through Hervey Bay to Maryborough, has long been within their path. Cyclones are not uncommon visitors here. In fact, they have shaped our coast, forests and local stories. Between the 1950s and 1970s, they were a regular part of life. Some years experienced two in quick succession. In 1976, we faced two within just a few days.

An old wives’ tale from Fraser Island is that when Eli Creek is running north, it signals a flooding wet season is on its way, and maybe even a cyclone or two. When it ran south, it would be dry. I don’t know how true it is, but I noticed the creek was running north in the lead up to the 2024-25 summer that spawned Cyclone Alfred.

The beach on the island’s west coast, north of Moon Point, was an important access route during emergencies when the tracks were closed due to storms and cyclones. Unfortunately, the southern beach profile at Wathumba Creek was altered near the side creek in the late 1980s, making the crossing virtually impossible. It was crossed daily in the 1980s.

Angela Burger recalls that after each cyclone, Dinah and Daisy, it wasn’t possible to drive along the beach for months while the sand gradually returned. People had to clamber over the exposed, craggy coffee rocks.

John Kitt worked for Forestry on Fraser Island as a cadet forester in the late 1960s. In his memoir, The Big Timberland – my life as a Queensland Forestry Trainee: Part Two, published last year, he mentions a cyclone that quickly intensified into an intense low depression in early 1968, crossing the coastline just north of Fraser Island. It dumped 28 inches (or 700 millimetres) at the Ungowa rain gauge. It is remarkable because 1968 is known as a “drought” year, with only another 100 millimetres falling for the rest of the year, fueling a severe fire season across the eastern seaboard.

Hervey Bay, with its wide, shallow waters and low-lying shoreline, faces one of the highest storm-surge risks along the Queensland coast. When cyclones approach, there’s nowhere for the sea to go but inland.

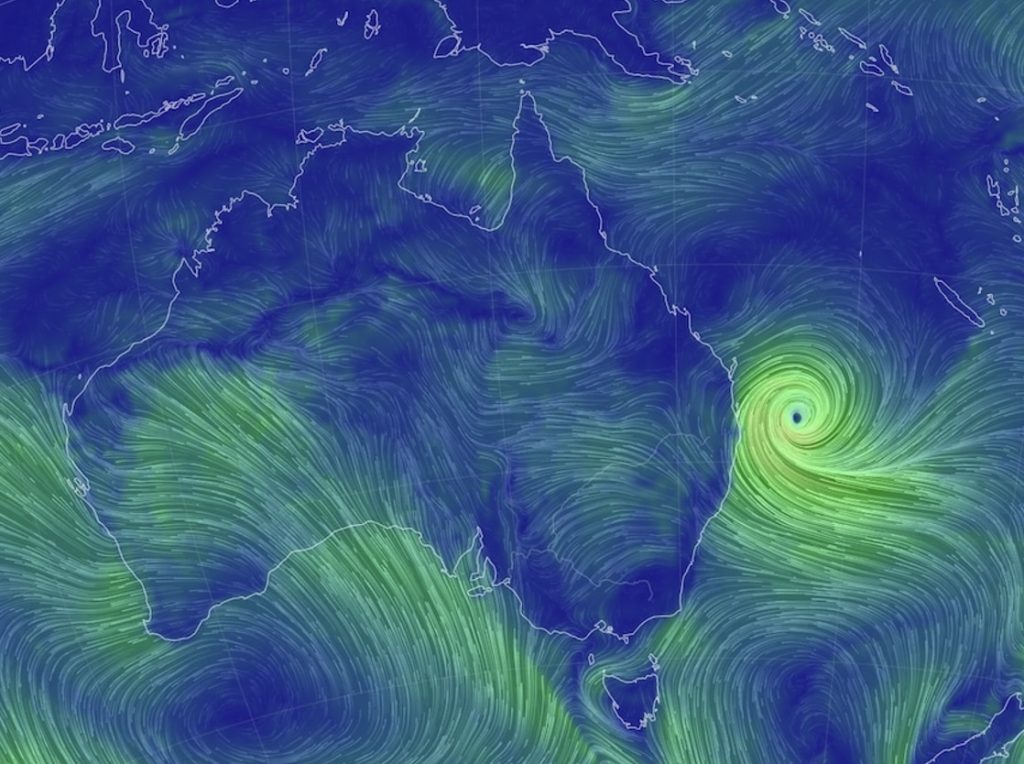

Tropical cyclones were once called “furious gales” until the term “cyclone” became common in 1893. They develop over warm tropical seas where hot, moist air rises and spirals around a low-pressure centre. They feed on ocean heat and humidity, spinning under the influence of the Coriolis effect. When conditions are right, that rotation intensifies into a vortex of rain, wind, and chaos. Predicting their exact path has always been difficult. Even with today’s technology, tracking a cyclone’s precise route can be tricky. Back in the mid-twentieth century, when meteorologists relied on limited observations and basic radar, forecasting was as much an art as a science.

Despite modern claims that global warming will cause more extreme cyclones, the long-term record tells a different story. According to CSIRO research, both the number and strength of cyclones across Australia have decreased since the early 1980s. Between 1935 and 1974, a cyclone hit as far south as Brisbane roughly every second year. For those of us who grew up on the Fraser Coast, wild weather was simply part of life.

Older locals still talk about the great storms of the past. Pharmacist and one-time tour operator on Fraser Island, Geoffrey McWilliam, once recalled a 1950s cyclone that stripped the beach between Eli Creek and Happy Valley of all its sand. He remembered:

It took three months for Jacob Lack to recover his truck stuck at Eli. That’s how long it took for the sand to return.

Huge seas, fueled by king tides, would wash right up to the toe of the high frontal dunes, eroding the sand and causing the dunes to slip. This was a common sight on the beach north of Waddy Point. According to Burger, during Daisy, 15-metre-deep slices were cut out of the dunes in some areas. A clear example of shifting sands and erosion is the Marloo wreck, which was beached near the shore at Orchid Beach in 1914. The wreck now sits further out to sea, about half a kilometre, even though it hasn’t moved.

Stories like that have become folklore, often passed down with a shrug and a smile, but each rooted in the reality of nature’s power. From the 1860s through the mid-1900s, the Fraser Coast experienced dozens of storms strong enough to flatten buildings, flood rivers, and reshape beaches. Ships were wrecked off Breaksea Spit and Inskip Point. The schooner Bounaparte lost both masts in 1863; the barque Panama broke apart in 1864, with ten lives lost. In 1870, Maryborough saw homes levelled by cyclonic winds. By 1873 and again in 1875, heavy rain and gale-force winds became part of life. Cyclones in the 1890s repeatedly battered the coast, bringing both destruction and the resilience that coastal living demands.

Throughout the early twentieth century, storms kept battering the region. In 1915, the Pialba school was blown down. Four years later, floodwaters from a cyclone at Maryborough tore up sections of the Mary Valley railway line. By the 1920s, storm surges were washing away beach structures at Pialba and isolating rail workers’ cottages on the west coast of Fraser Island. The pattern continued through the 1930s and 1940s: hotel roofs torn off, ships abandoned in heavy seas, and repeated flooding rains.

By the 1950s, storms still struck, and some were fierce. In 1953, a Christmas Day cyclone hit Tin Can Bay, and in 1955 Bundaberg experienced record flooding on the Mary River. In April 1963, a massive cyclone sent swells across more than 500 kilometres of coastline, claiming lives and eroding beaches from Hervey Bay to Noosa.

Reg Barnewall refers to Cyclone Angela in mid-November 1966 in his book about Orchid Beach:

Battened down, we waited for the inevitable increase in wind strength and spent a sleepless night, although the reports on the radio indicated that the depression was downgraded to a severe tropical storm. It wreaked severe damage to the Bundaberg districts, virtually wiping out all crops, especially tobacco, before petering out in northern New South Wales.

However, I can’t find any reference to this cyclone online or in the newspapers. If anyone recalls an event around that time, please let me know by leaving a comment on this blog.

Of course, we all know about the damage to Orchid Beach from the cyclones in the 1970s, when the steps to the beach were taken down, replaced, and then closed. And, most graphically, the pool was undermined by successive cyclones and storms, and eventually broke down during a wild winter storm in the late 1970s.

The period most locals recall best is the decade from 1967 to 1976, when the Fraser Coast faced a relentless barrage of cyclones — each with its own story to tell.

Dinah – January 1967

Cyclone Dinah remains etched in memory as one of the fiercest to ever threaten southern Queensland. Forming in the South Pacific, she grew into a Category 4 storm as she moved southwest. “It shows promise of being a bad one,” a Weather Bureau spokesman warned, and he wasn’t wrong. When Dinah swept past Fraser Island on 29 January, the Sandy Cape Lighthouse recorded a minimum pressure of 944.8 hPa, which is the lowest ever observed there.

Maryborough bore the worst impact. Gale-force winds battered the city for hours, ripping roofs off houses and cutting power and phone lines. The Lady Musgrave Maternity Hospital lost its roof. Roads became impassable and the town was cut off. In Hervey Bay, campers ran for safety as news spread of an approaching cyclone. Wind gusts hit 160 kilometres per hour, uprooting trees along the foreshore and sending waves crashing over the beach. Houses in Torquay and Urangan flooded, and residents in low-lying Cypress Street evacuated as septic systems overflowed.

Sue Birgan’s parents had only moved to Hervey Bay the year before and taken a lease of the kiosk at Anchorage Caravan Park at Urangan, and also operated a boat hire business. As the cyclone approached, her father hauled the boats out of the water, turned them upside down, and tied down the iron roof on the kiosk and their residence. She remembers the roof lifting during the storm, the eye passing over, and the high tide reaching a couple of inches below their floorboards. Without power for a few days, Sue and her brother thought it was a great experience as they got to scoff down all the ice blocks from the deep freezer before they melted into a blob.

Fraser Island sustained relatively minor damage. Sand was whipped into drifts so thick that Happy Valley was described as “white as snow.” However, the mainland bore the full force of Dinah. A later insurance study ranked it as the third most costly cyclone in Queensland’s history when adjusted for modern values.

Dora – February 1971

Cyclone Dora arrived four years later, crossing near Caloundra on 17 February. She wasn’t the strongest on record — a Category 1 storm — but she packed a punch. For more than a day, torrential rain hammered the Wide Bay, dumping 225 millimetres in 27 hours. On Fraser Island, a builder named Sid Melksham became a local legend. He’d just fastened new sheets of corrugated iron to a roof when the cyclone hit. Fearing the iron would tear away, he had himself strapped spread-eagled to the roof and stayed there through fifteen hours of wind and driving rain, holding it down until Dora passed.

That summer experienced unpredictable weather. The Weather Bureau attributed it to blocking high-pressure systems over New Zealand that stalled tropical lows, directing moisture towards Queensland’s coast. They described it as “conducive to cyclonic weather”, a relatively modest way to acknowledge the soaked summer it brought.

Daisy – February 1972

The following year, Cyclone Daisy hit Fraser Island on 11 February as a Category 3 storm. She was unpredictable, changing course twice in a day before making landfall late at night. The Sandy Cape Lighthouse recorded a pressure of 968.8 hPa as Daisy arrived with 180-kilometre-per-hour winds.

At Eurong, John Kingston remembered rain pouring through the windows until the floor was covered with about three inches of water. When he went out to fetch firewood, the wind was so fierce that he had to crawl back. At 2 am, silence settled under the ghostly calm of the eye before the wind blew again from the opposite direction. Houses were flattened at Poyungan Rocks; roads were blocked by fallen timber. Forestry Ranger Dick Jones claimed Daisy was “far more frightening than Dinah.”

In Hervey Bay, over 200 homes were damaged, and hundreds of trees were lost from the once-shaded foreshore. Residents feared erosion without their roots to hold the sand in place. The beach near the QTM mineral sands operation was scoured bare, but, ironically, the prized, fresh black mineral deposits were uncovered by the storm

Wanda, Pam, and Zoe – 1974

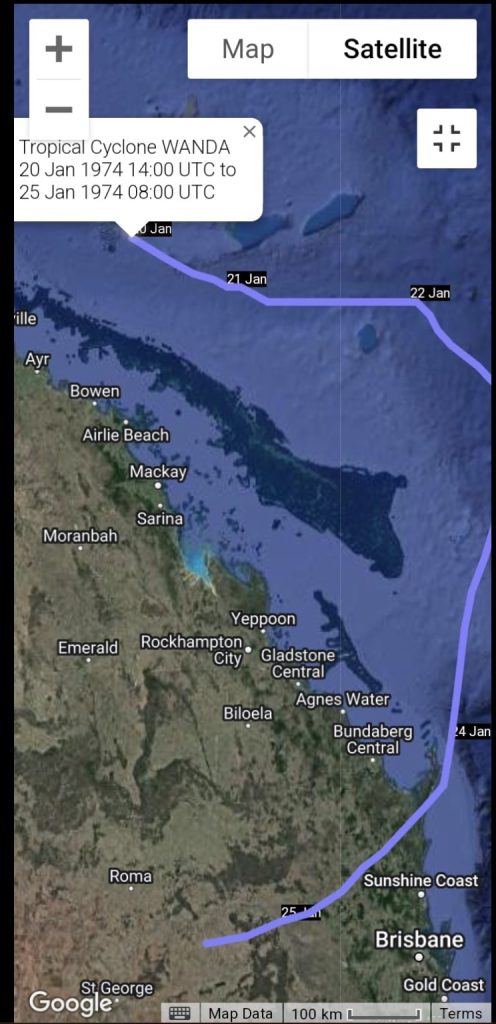

By 1974, the rain hardly seemed to cease. Cyclone Wanda struck near Maryborough at the end of January, bringing three solid weeks of rain. Despite being only a Category 2 storm, Wanda dropped an incredible 1,050 millimetres in two days in parts of southeast Queensland. After it crossed the coast, it dragged all the tropical moisture towards south-east Queensland and then stalled, leading to the savage flooding event that impacted Brisbane and the Fraser Coast.

Camps at Eli Creek were waterlogged, and roads became rivers. Ken Holzheimer recalls packing up their camp at Eli Creek and battening down the mining road as the eye of the cyclone passed over, then blowing like crazy in the other direction.

A week later, Cyclone Pam formed offshore. It was a massive storm spanning two million square kilometres of ocean, with winds of 250 kilometres per hour at its centre. Luckily, it remained mostly at sea, though its huge swells damaged beaches along the Gold Coast and caused waves to crash up to Fraser Island.

Then, in early March, yet another system formed. Cyclone Zoe passed about 200 kilometres east of Maryborough, bringing strong south-easterlies and more flooding rains. For weary residents, it felt like an endless summer of storms.

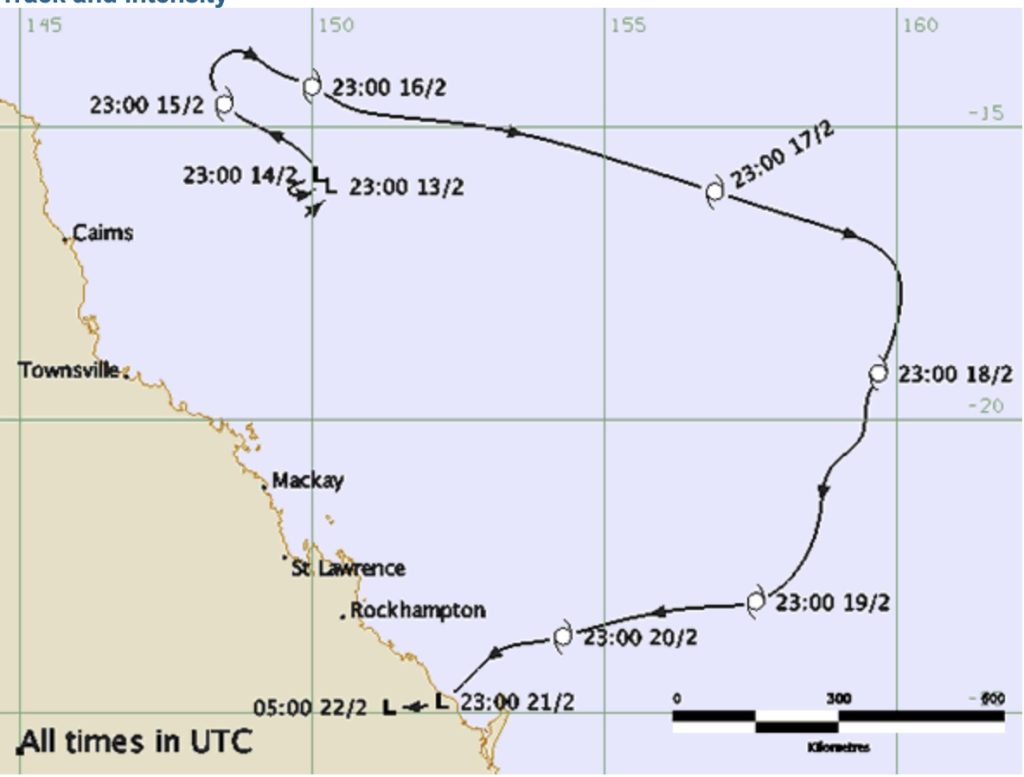

Beth, Colin, and Dawn – 1976

By the time Cyclone Beth appeared in February 1976, locals had grown used to the routine — tie things down, fill the water tank, and wait. Beth formed near Willis Island and made landfall just north of Bundaberg, bringing heavy rain and causing power outages from Maryborough to Hervey Bay. Confusion reigned when the Weather Bureau initially dismissed it as a “weakening low.” By morning, it was “blowing like the clappers.” Beth created a massive tidal surge and waves that lashed the coast, particularly Seventy Five Mile beach on the island.

The failure of the new Mt Kanighan radar station to provide warning infuriated local officials, who demanded that the Bureau man it continuously during cyclone season. Their frustration was justified after roads were cut, homes unroofed, and up to 200 millimetres of rain fell in less than a day. Waves up to ten metres pounded the beaches.

Just eight days later came Cyclone Colin, another tropical low tracking southward, skirting 220 kilometres east of Fraser Island. Schools closed early as rain sheets swept across the region. Colin never made landfall but drove huge swells onto the coast, eroding dunes and reshaping beaches from Noosa to Hervey Bay.

Then, as if that weren’t enough, the very next day saw Cyclone Dawn move down from north Queensland, crossing Fraser Island the following day as a severe tropical low. It dumped 230 millimetres of rain between Proserpine and Maryborough.

Three cyclones in barely two weeks were a grim reminder of how common these events once were.

From Simon to Alfred – the later years

The pattern continued into the 1980s and beyond. Cyclone Simon in 1980 veered within 30 kilometres of Fraser Island, bringing 100-knot winds and eroding beaches. The following year, Cyclone Cliff crossed the island, cutting power and flooding towns. I vividly remember that one as I taped my bedroom windows in our old Queenslander in Maryborough, bracing for the worst the news forecasted.

In January 1992, Cyclone Betsy hit the region hard, followed by Roger and Fran in 1993. Each brought more flooding and erosion. Then came Hamish in 2009, a Category 4 cyclone that initially appeared destined for Hervey Bay before turning east at the last moment. With a central pressure of 925 hPa, it ranked among Queensland’s most intense storms, comparable, in some ways, to America’s Hurricane Katrina.

I also remember Oswald in 2013. Though it only briefly reached cyclone strength before tracking inland, it dumped record rain. Maryborough saw its third-highest flood that Australia Day weekend. I was living in Granville at the time. The heavens opened after months of dryness, and within hours, we were cut off from the rest of town. From our verandah, we watched the floodwaters rise and then linger for days under bright sunshine.

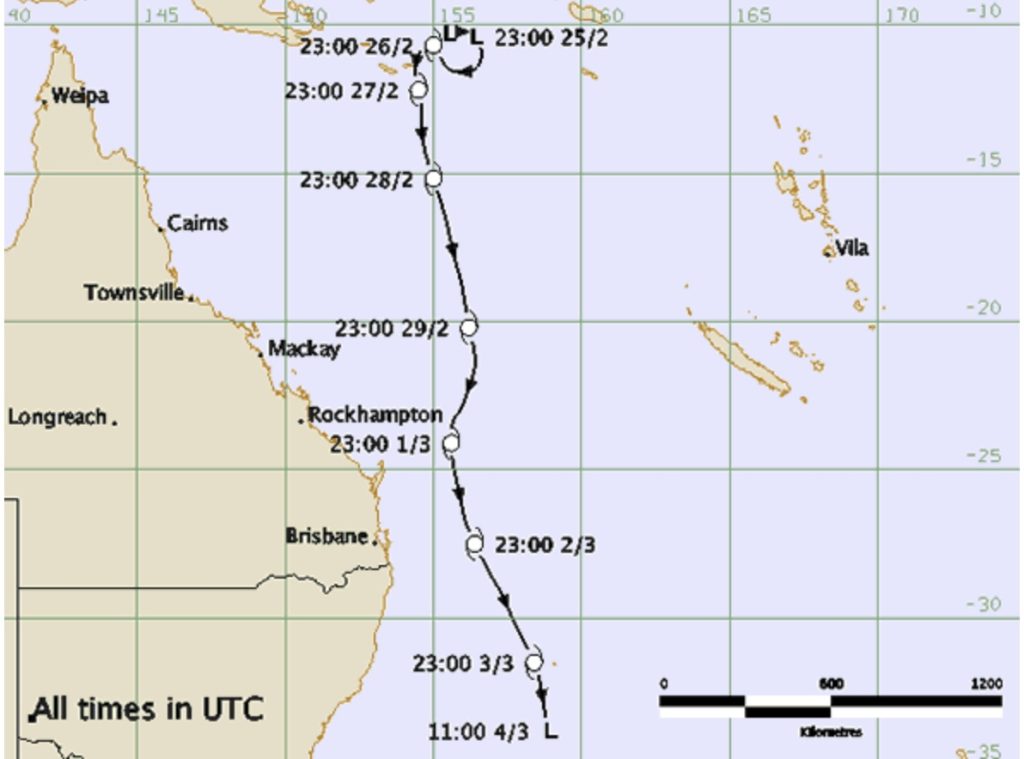

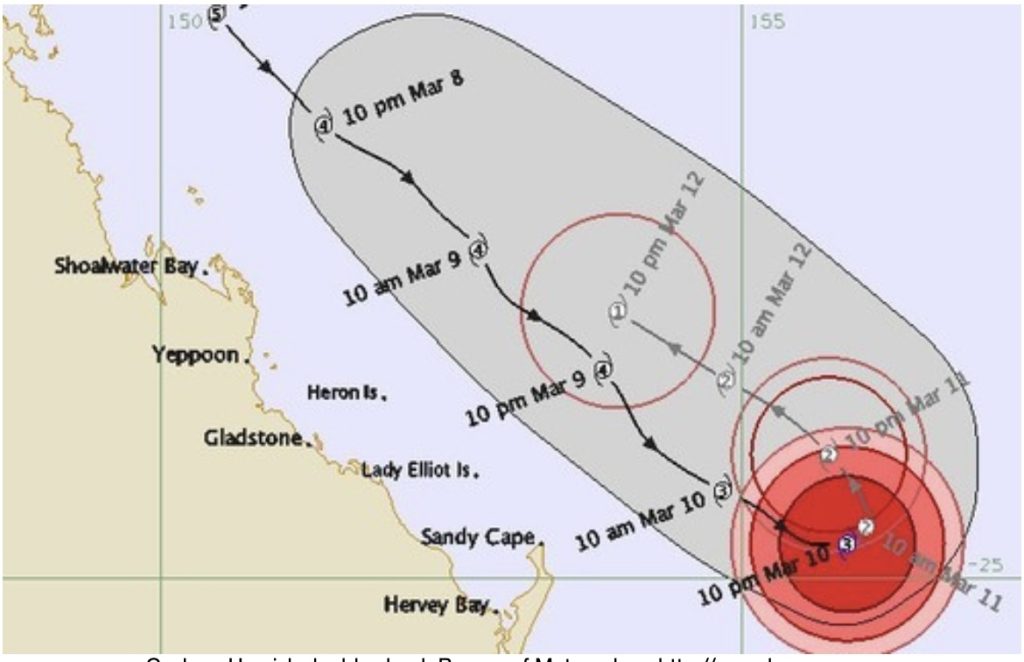

Cyclone Marcia, which started in mid-February, was a very powerful but small storm that travelled a long distance before making landfall at Rockhampton and Yeppoon. It is the most intense cyclone to make landfall so far south on the east coast during the satellite era.

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, it passed just to the west of Yeppoon as a Category 5 system, then over nearby Rockhampton as a Category 3. Over 60,000 homes lost power. Wind gusts of more than 50 kilometres per hour hit the Fraser Coast as the ex-cyclone passed over the district.

The Bureau continued to report its estimated wind speeds even after lower actual wind speeds were recorded. Jennifer Marohasy criticised the Bureau for its inaccurate and irresponsible forecasts. She claimed they used computer modelling rather than early readings from weather stations to determine that Marcia was a Category 5 cyclone, not a Category 3.

Some people believed it was dangerous for residents to think they survived a Category 5 event when it was really a severe storm that degraded quickly.

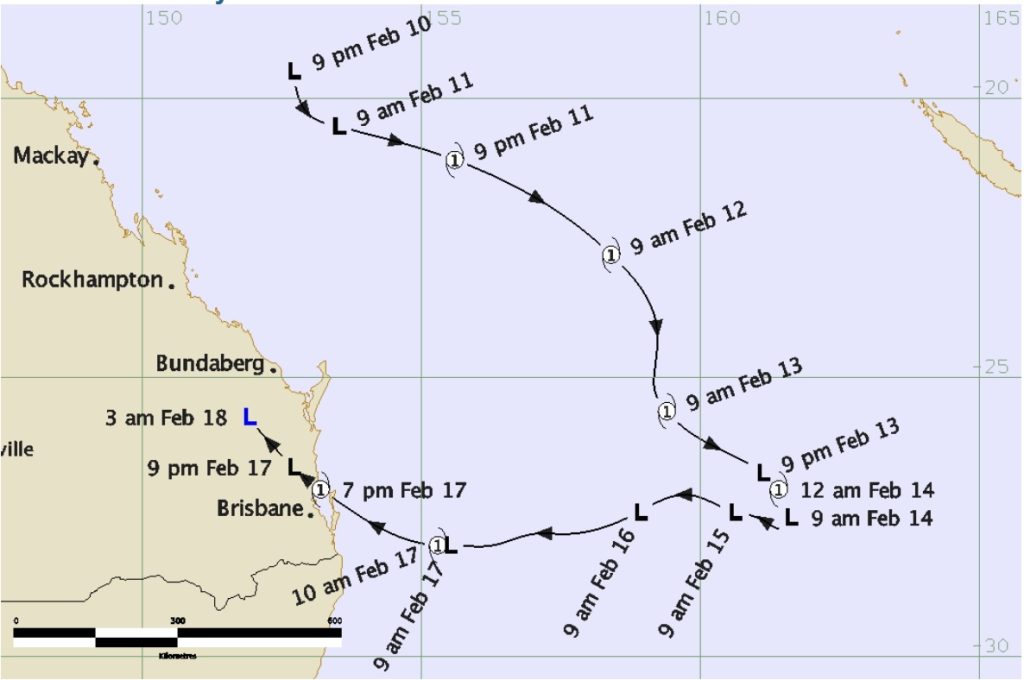

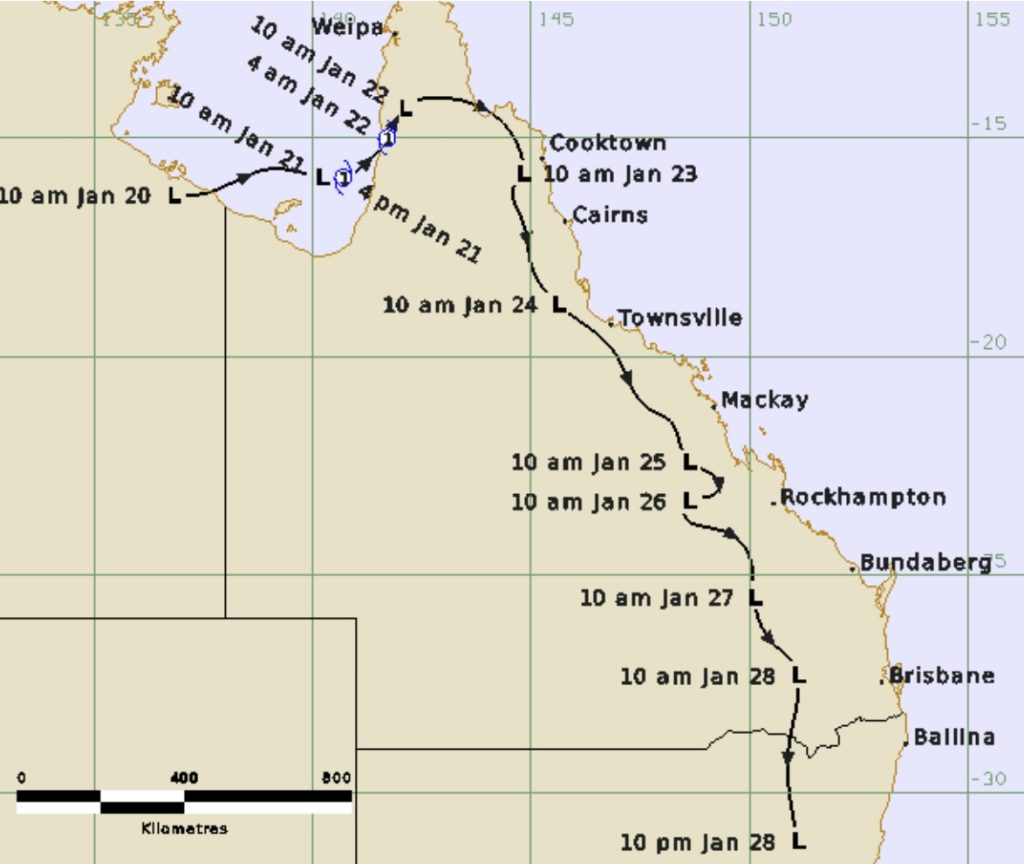

And then, last year, came Alfred. Born as a tropical low northeast of Cooktown, Alfred drifted offshore, gathered strength, and turned abruptly toward the coast as a Category 1 storm. On 9 March, Hervey Bay bore the brunt. More than 300 millimetres of rain fell in six hours, causing flash flooding that swept cars off roads and caught residents by surprise.

I woke early that morning, planning a bushwalk through the Toogoom forests, just north of Hervey Bay. The sky didn’t look threatening, and the radar showed nothing untoward, so we went for the walk with little rain but still very overcast. A few hours later, the Bay was buried beneath sheets of rain that we could see from a vantage point. I struggled to drive home through flooded streets. I had to leave my car at a friend’s place and wade home through rising water.

When the storm passed, anger arose, not just over the damage but also the lack of warning. The Riviera Resort was one of the hardest hit, with its underground car park flooded and power outages lasting a week. The Fraser Coast mayor demanded answers from the Bureau of Meteorology. It was a familiar story — one that echoed the frustrations heard half a century earlier after Cyclone Beth.

Echoes of the past

Looking back across more than a century of storms, one truth stands out to me. Cyclones have always been part of life on the Fraser Coast. They shaped our dunes, our forests, and our towns long before “climate change” entered the vocabulary. From the schooners wrecked off Breaksea Spit in the 1860s to the flash floods of Alfred in 2025, each storm has left its mark.

For those of us who live here, these are not much more than meteorological events. They are shared memories of the roar of wind through she-oaks, the sound of rain on corrugated iron, the sudden silence when the eye passes overhead. All these things remind us of our connection to the region. The cyclones we have endured in the past weren’t merely disasters; they were tests of endurance, shaping a community that knows how to survive, rebuild, and remember.

Perfect timing, I met a lady yesterday, Kathy Oxborough, who also lived at Tewantin when Cyclone Annie struck on the night of New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1962. It hit around 11 PM, the building shook, and Mum was worried it would be blown off the stumps.

The next morning, I rode my bike around looking at the damage. The campground was a mess. All that remained of an old bondwood caravan was the floor and wheels. A shed and other debris had been blown into Lake Doonella.

Cyclone Annie struck the Sunshine Coast and Noosa area on New Year’s Eve 1962 and into New Year’s Day 1963, causing severe damage with wind speeds reaching up to 90mph (approx. 145km/h. It devastated coastal campsites, particularly in the Noosa Woods and Cotton Tree areas, destroying tents and overturning caravans.

Thank you. Good read as always.

What a great read, absolutely awesome, many thanks.

Cyclone Angela in November 1966 centred on the Solomon Islands, and it seems it was not recorded as a “Queensland cyclone” although its influence was apparently felt in Bundaberg and on FI. I lived in Beerwah then and don’t recall any 1966 cyclone, but I do recall Cyclone Annie on New Year’s Day in 1963, which came ashore at Tewantin and caused a lot of damage to Noosa, Caloundra, and Buderim. Probably too far south to cause any strife on Fraser Island. We had slash pines in the Beerwah plantations, 25 m tall, bending nearly horizontal during the night, and young plantations blown over.

Thanks, Ian. I suspect Reg had his year and/or month wrong, although I thought about it a lot because his association with the island was short.

John Huth sent me a nice summary, prepared by a retired meteorologist, on “East Coast lows”. I had seen it and took notes for my story, particularly of the much earlier events. It seems I may have overlooked the 1960s ones – there is just so much conflicting information about that period and exact dates. Just goes to show, it was a busy cyclone decade!

This was a very interesting and informative article. Thanks for all the effort you put into creating this as a sequence of storms. As a relative new comer to Hervey Bay, I have found it particularly interesting.