Pioneering the Burnett

When surveyor John Charlton Thompson first mapped out Bundaberg in the early 1870s, few could have imagined that the small settlement on the Burnett River would eventually become the beating heart of one of Queensland’s most renowned agricultural industries. At that time, the district’s pioneers were still finding their way, clearing dense forest, testing the soils, and searching for a crop that could bring prosperity.

The Burnett River flats, with their volcanic soils and plentiful rainfall, proved perfect for growing sugar cane. Cane had been tested in Brisbane and Maryborough since the 1860s, and the idea quickly spread north. By 1870, the first crops were planted on the Burnett by settlers like John and Gavin Steuart and the Huxley brothers. It was as much an act of faith as an enterprise, even though the climate looked ideal, but the work was tough, and success was far from certain.

Early mills were makeshift setups, often powered by bullocks or basic steam engines. Cane crushing was carried out by hand or with small rollers, and the juice was boiled in open pans to make raw sugar or molasses. Yields were low, but the potential was clear. Bundaberg’s early settlers believed they were on the verge of something transformative — an industry that could lift the entire district.

The promise of a sweet future

The 1870s and 1880s brought a wave of optimism. With the success of early plantations along the Burnett, new settlers arrived in droves, carving out farms from virgin scrub. Land values rose, and small communities sprang up around the mills. Cane became the region’s defining crop. It became the plant that dictated the rhythm of life and the soundscape of the town.

Among the first to recognise the potential of Bundaberg sugar was businessman and entrepreneur Frederick William Buss, who, along with his brother Charles, set up a general store and shipping business. The Buss family quickly became a key part of the district’s commercial scene, their enterprise linking local growers to the broader world beyond the Burnett. They later helped establish the company that would run the Millaquin Sugar Mill, one of Bundaberg’s notable industrial landmarks.

By the late 1880s, Bundaberg’s sugar not only met local demand but also reached overseas markets. The region’s prosperity drew engineers, merchants, and labourers from across Australia and beyond. Sugar had become more than just a crop. It was a symbol of progress, a source of civic pride, and the core of Bundaberg’s identity.

The human cost: South Sea Islander labour

But prosperity had its price. The industry’s success depended heavily on cheap, reliable labour, and the subtropical climate made European workers scarce. The reality was that Queensland sugar cane farmers faced significant hurdles in terms of competitiveness due to high labour costs compared to those in other nations. For instance, in Mauritius, labour cost was 1 shilling per day with no rations; in Java, it was 6 pence per day; and in Fiji, it was 1 shilling per day. In Queensland, all expenses, including wages, rations, and provisions for return, were 16 shillings per week per worker.

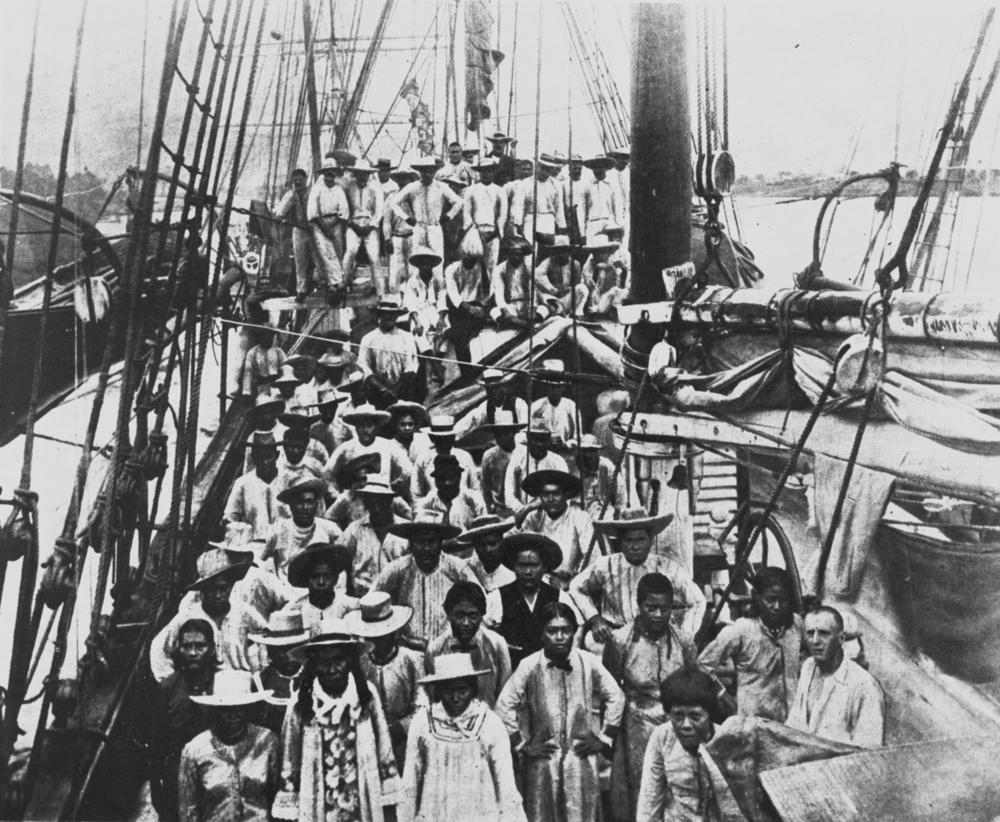

Beginning in the 1860s, thousands of South Sea Islanders, often called “Kanakas”, were brought to Queensland under what was euphemistically called the “labour trade.”

Many of these men and women came from islands like Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands. Some came voluntarily, lured by promises of pay and adventure; others were coerced or outright kidnapped in a practice that would later be condemned as blackbirding. They worked long hours in brutal conditions, planting, weeding, cutting, and loading cane by hand in the oppressive heat. Living quarters were basic, rations meagre, and disease was rife.

The death toll among Islander workers was high, and few saw the full measure of their wages. Yet their contribution was immense. Without their labour, Bundaberg’s plantations could never have expanded as they did. They cleared the land, dug the drainage, tended the cane, and kept the mills turning.

In the early 1900s, under the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, most Islanders were forcibly repatriated as part of the new Commonwealth’s White Australia Policy. That was because conditions on many of their home islands were far from perfect due to inter-tribal wars. But not all left. Some relocated to Moa Island in the Torres Strait to a Church of England mission. A few remained, marrying locally and contributing to Bundaberg’s cultural mosaic. Their descendants still reside in the region today, marking a quiet, living legacy of a challenging chapter in Queensland’s history.

Mills, machines, and magnates

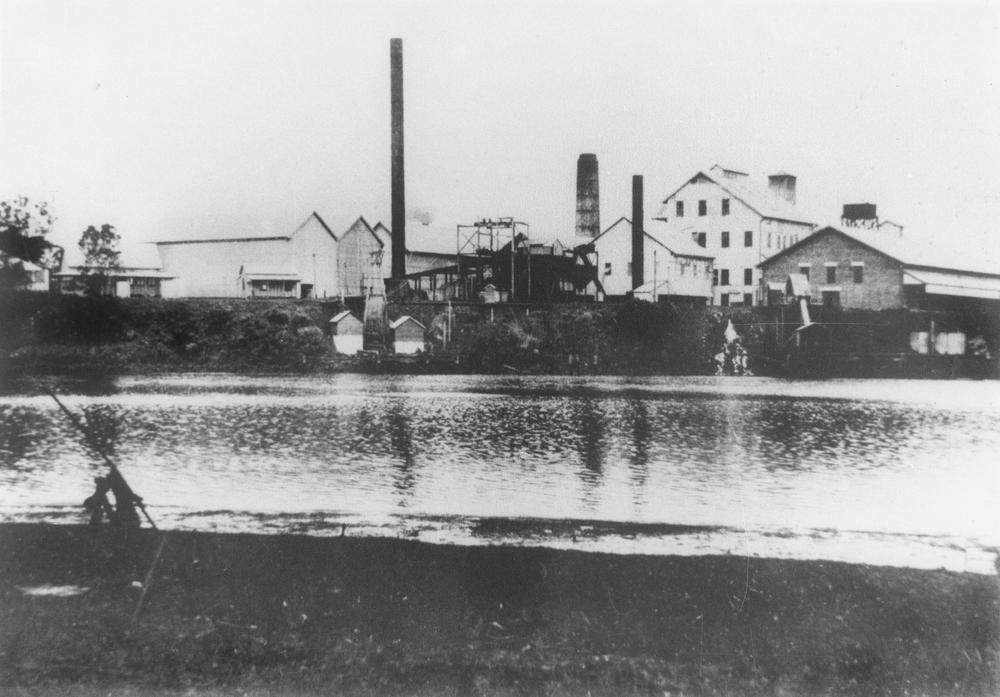

As Bundaberg’s plantations grew, so too did its mills. The Millaquin Mill, established in 1882 on the south side of the Burnett River, was among the first large-scale operations. Financed by local investors and managed by skilled engineers, Millaquin became a technological marvel for its time. The mill’s success cemented Bundaberg’s reputation as a centre of industrial innovation in Queensland’s north.

Not far away, the Bingera Mill was founded in 1885, supporting growers along the north bank of the Burnett and later around Gin Gin. Bingera would last for more than a century, outliving many of its peers and becoming a synonym for the Bundaberg sugar brand. Smaller mills like Fairymead and Qunaba, among others, dotted the landscape. Each served its own group of growers and contributed to the local economy.

The Fairymead Plantation, established by the Young family in 1879, was another cornerstone of Bundaberg’s sugar industry. The Youngs, Scottish migrants with engineering expertise, introduced advanced machinery and techniques from overseas, helping push Bundaberg to the forefront of Queensland’s sugar production. Fairymead’s extensive fields, tramways, and mill complex became a showcase of efficiency and innovation.

These mills did more than process cane. They built communities and entire villages of workers, engineers, and families who lived by the rhythms of the crush. The whistle of the mill became the heartbeat of Bundaberg life, signalling shifts, meal breaks, and the start and finish of the season.

From molasses to legend: the rise of Bundaberg Rum

By the late 1880s, Bundaberg’s sugar mills were making more than just sugar. Each crush season left behind large amounts of molasses, the thick, syrupy by-product of the refining process. For most millers, it was a nuisance, only suitable for stock feed or dumping into the Burnett River. But a few clever locals saw potential where others saw rubbish.

In 1888, a group of Bundaberg entrepreneurs and sugar industry figures, including Frederick Buss, the Watson brothers, and the Young family of Fairymead Plantation, decided to turn this surplus sticky molasses into something profitable. Combining their resources, they established the Bundaberg Distilling Company and built a modest still by the Burnett River, not far from the Millaquin Mill. Their practical and straightforward idea was to convert molasses into rum.

The distillery’s fortunes fluctuated with the sugar industry. When cane harvests were bountiful, molasses was abundant, and production thrived. When floods, droughts, or disease diminished the crop, the stills went silent. In this way, Bundaberg Rum was inextricably linked to the rhythms of the cane fields. It was a liquid mirror of the district’s agricultural ups and downs.

By the early 20th century, Bundaberg Rum had built a reputation for its rich flavour and strength. It became the preferred drink of cane cutters, mill workers, and drovers, as well as a popular export. Locals joked that the rum was so potent it could “put hair on a sugar mill’s chimney,” while others believed it cured everything from snakebite to heartbreak.

The distillery faced its fair share of troubles. Fires in 1907 and again in 1936 both destroyed the facility, causing rivers of burning rum to flow into the Burnett River. Yet, like the sugar industry that kept it afloat, the Bundaberg Distilling Company rebuilt each time, more resilient and determined than ever.

The partnership between sugar and rum was both economic and symbolic. Both industries required skill, patience, and a readiness to risk against nature. Both arose from the same raw material, the same soil and the same pioneering spirit.

Over time, Bundaberg Rum evolved into more than just a drink; it became an integral part of the region’s identity. Its distinctive polar bear logo, introduced many years later, helped make it one of Australia’s most recognisable brands. However, behind that success were the hard work of cane cutters, the skill of millers, and the entrepreneurial spirit of Bundaberg’s early sugar pioneers.

During the peak of the sugar industry in the mid-20th century, the distillery remained a vital economic hub in the town, sourcing molasses from local mills and employing hundreds. Its presence helped stabilise the market for sugar by-products, ensuring that nothing from the cane was wasted.

In many ways, Bundaberg Rum was and still is the distilled spirit of Bundaberg’s sugar heritage. Strong, enduring, unmistakably Queensland, and born from the land that gave it life.

Today, the distillery is a major tourist attraction, hosting over 80,000 visitors a year.

Triumphs and trials

The early 20th century brought both growth and challenges. The sugar boom of the 1910s and 1920s made Bundaberg one of the wealthiest towns in Queensland. Railways reached deep into the cane fields, helping growers transport their harvests smoothly to the mills. A network of narrow-gauge tramways dedicated to hauling cane spread across the district, showcasing both the industry’s cleverness and its massive scale.

Yet the boom years were marked by hardship. Floods periodically flooded the low-lying farms along the Burnett, while droughts challenged even the most experienced growers. Cane beetles and rats destroyed crops, forcing scientists to find new pest control methods. The Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations, established in 1900, became a crucial partner, researching better varieties of cane and more efficient milling practices.

Economic depressions and world wars disrupted trade. The Queensland government’s Sugar Experiment Stations and Central Sugar Cane Prices Board helped stabilise prices and support growers through difficult times. By the 1930s, Bundaberg’s mills were among the most advanced in the southern hemisphere, and its growers among the most skilled.

Life in the cane country

Sugar shaped every part of Bundaberg’s social fabric. The cycle of the seasons governed the rhythm of life. Planting started after the summer rains; harvesting, known as “the crush”, brought months of long, hot work and the constant drone of machinery. Families measured time not in years but in crushes.

The sugar cane plant grows for 12-16 months before being harvested between May and December each year.

Cutting cane by hand was backbreaking work. Teams of “cutters” armed with razor-sharp knives worked from dawn to dusk, slicing through the dense stalks and stacking them for transport. It was a dangerous, exhausting labour, and the cutters — many of them Italians, Maltese, and later the descendants of Pacific Islanders — developed a fierce camaraderie as they toiled in the sub-tropical heat and humidity. Compared to cane-cutting, cutting timber in the forest was child’s play.

One veteran cutter recalled:

You’d feel the heat coming off the cane like a furnace. You’d swing all day, sweat pouring, your hands raw. But when the whistle blew and the mill lights came on, you knew you’d earned your pay.

Entire generations grew up near the mills. The sugar companies supported social clubs, schools, and churches. Sports teams carried the names of mills — Fairymead Cricket Club, Millaquin Footballers — and annual events like the cane-cutting competitions attracted large crowds.

These were the men and women who kept Bundaberg’s sugar flowing. The anonymous heroes whose labour powered an industry.

Innovation and modernisation

By the 1950s, mechanisation was transforming the cane fields. The introduction of mechanical harvesters revolutionised the industry, reducing dependence on manual labour and enabling farmers to boost production. Cane transport also evolved from bullock drays to light rail, and eventually to diesel trucks that could move cane more efficiently over longer distances.

Heavy-duty harvesters replaced the cane cutters. They now move along rows of sugarcane, removing the leafy tops, cutting the stalks at ground level, and chopping the cane into small lengths called billets. These are loaded into wire bins, which are then towed by a tractor to a tramway siding or road haulage delivery point for transportation to the sugar mill.

After harvesting, the stubble left behind regrows, producing a ratoon crop. Two to four ratoon crops are usually grown before the land is rested or planted with an alternative crop, such as legumes, ploughed, and replanted to start the cycle again.

The Bonel Brothers of Bundaberg developed a thriving local business when they began making sugar cane planting and cultivation machinery for their own farm. They were immigrants from Italy and started small, designing and building a single-furrow mouldboard plough. It became so popular that they created a foundry and later a small factory.

The brothers were very successful in maintaining a good portion of sugar cane implement sales in the Bundaberg district, against larger corporate and international competitors. Many innovative designs were introduced, including the first-ever working reversible plough. During the 1960s, they designed and built the Bonel plant-cane cutter, which helped revolutionise cane harvesting. Other local manufacturers of machinery were Cantec and Austoft.

Mills modernised their equipment by introducing electric drives, better boilers and automated juice clarification systems. The once rustic operations of the 19th century had become sleek, industrial powerhouses. Bundaberg’s mills exported refined sugar across Australia and overseas, earning the region international recognition.

While machines brought efficiency, they also altered the character of the industry. The old gangs of cutters disappeared, taking with them part of Bundaberg’s working-class culture and with them a proud sense of heritage.

Green cane harvest

Until the early 1940s, most sugar cane in Australia was cut green by hand and then topped and loaded manually. From World War II onwards, burning became the standard practice after severe outbreaks of Weil’s disease, a potentially fatal disease spread by rats in the cane. As a result, farmers acquired significant expertise in burning limited areas without imperilling their neighbours’ crops or their own. There was also an added bonus. Burning and a change in the manual harvesting method increased the daily output per cutter from six tonnes a day to approximately nine tonnes. As well as significantly reducing the volume of leaf matter, burning made it easier to cut and load the cane.

However, in 1976, a very wet season in North Queensland prompted the reintroduction of green cane harvesting after a gap of over 30 years. Although cane fires are still regarded as a tourist attraction, pre-harvest burning of sugar cane has become a sensitive environmental issue.

Green cane harvesting and the associated spreading of leaves and other plant residue in a thick layer of mulch over the ground provide agronomic benefits, as well as improved flexibility in harvesting. Trash blankets help suppress weed growth, reducing the need for frequent cultivation and spraying, while retaining soil moisture and reducing soil erosion. Harvesting is still possible when wet weather prevents burning, and there is no delay when heavy rain or unfavourable wind occurs.

Cane losses during harvesting are much higher than for burnt cane. While losses can be reduced by modifying harvester design, there are usually higher levels of extraneous matter in the cane supply.

However, not all farms can use this method due to climatic and technical constraints, which have led to slow adoption in the southern regions and parts of north Queensland. Green cane trash blanketing is not suitable for poorly drained blocks or for cold conditions. Significant yield losses may occur due to poor germination and slower growth.

Harvesting green costs more because cutting rates are lower than in burnt cane.

At its peak

Between 1875 and the 1890s, 36 sugar mills and 14 juice mills were built in the Bundaberg district to crush sugar cane from surrounding plantations. By the mid-20th century, Bundaberg was a name synonymous with sugar. The district’s mills processed hundreds of thousands of tonnes of cane each year, and its refined sugar was among the best in Australia. From Fairymead to Bingera, Millaquin to Qunaba, the chimneys puffed sweet-smelling steam during the long harvest months, while the fields around them shone green and gold under the Queensland sun.

Bundaberg was, in every sense, a sugar town. Mill stacks defined its skyline; its economy was tied to the price of sugar; its people were bound by the rhythm of planting and crushing. The town’s streets bustled with engineers, mechanics, labourers, and merchants whose livelihoods all traced back, one way or another, to the cane fields.

The prosperity of those years funded Bundaberg’s civic growth, including the construction of new schools, hospitals, and community facilities. As the town’s reputation spread, its name carried far beyond Queensland by bottles of Bundaberg Rum and bags of Bundaberg Sugar.

Cane pest and disease

Pests and diseases have been significant factors in cane growing from at least the 1870s, when cane grubs and a disease called ‘rust’ began to attack cane. The pest and disease control system in Australia, including the role played by Pest Control Boards, was unique in the sugar world until the 1980s. It came about through necessity, but was achieved and successful due to cooperation between all parts of the sugar industry and the Queensland Government.

However, it is also worth noting that Australia’s most infamous and disastrous biological control introduction, the cane toad, was also part of the system that troubled the industry.

The legacy

The golden age of Bundaberg’s sugar industry wouldn’t last forever. In the following decades, global price pressures, rising labour costs, and competition from other crops began to reshape the region’s economy. Nonetheless, in the mid-20th century, the industry remained proud, productive and deeply woven into the town’s identity.

Its legacy endures in the landscape through the old mill stacks, the tramway lines overtaken by grass, the grand homesteads of pioneer families, and the lasting names that continue to shape Bundaberg’s character. It lives on in the descendants of the South Sea Islanders, the engineers still working at the refineries, and in the community’s shared memory of a time when sugar was more than just a business; it was a way of life.

Today, Bundaberg Sugar’s mills have a daily crushing capacity of over 15,000 tonnes of cane and produce more than 220,000 tonnes of raw sugar annually.

Epilogue: a sweet heritage

From the first fragile canes planted along the banks of the Burnett to the grand mills that once graced the horizon, the story of Bundaberg’s sugar industry is one of grit, resilience, and change. It shaped the land, built a community and sparked the growth of one of Queensland’s key regional centres.

Even today, when the breeze carries the faint scent of molasses from the distillery, it feels as if the past whispers through the fields. When it does, it serves as a reminder of the men and women who transformed a wild frontier into a sugar empire, and in doing so, built the city that still bears the sweet mark of its origins.

Good summary Robert. Of particular personal interest as my mother’s family were cane farmers at Glen Gowrie east of Bundaberg in the 1880s. One major area you have missed is the fundamental contribution of the cane tramways with their small steam locos including those manufactured locally at Fowlers in Bundaberg and those WW1 repurposed Hunslets amongst others that served the industry for decades until gradually replaced with Clyde diesels, which still serve the industry today: a colourful history in its own right.

Good article. Thanks, Robert. A little additional info “The Noakes brothers were pioneers of Bundaberg and its sugar industry. They were inaugural shareholders in the Distilling Company”. https://www.bundabergrumshowcase.com.au/springhillhouse.html.

Also, if not already seen, Chapter 6 in this paper has good information on the sugar industry in Bundaberg – https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/data/UQ_185026/THE3927_e1.pdf

Thanks for this. I really enjoyed reading it.

Thanks Robert, an excellent article on an area close to my heart.

As you know, quite a lot of old cane land around Bundaberg is now farmed for high-value crops such as sweet potatoes and macadamia nuts. Quite an amazing transition in itself.

The sweet potato farms around the Hummock east of Bundaberg have become prone to erosion as a result.

This was almost non-existent when cane was grown. The runoff from the sloping red soil now leaves a red “slick” out to sea after heavy rainfall. In hindsight, the “ratoon” nature of sugar cane cropping was the key to protecting the valuable red top soil and was very important as a land management strategy.

No mention of German influence and investment playing a significant role in the development and modern operations of the Bundaberg and broader Queensland sugar industry, spanning from early pioneering efforts to recent corporate acquisitions. The development of Bundaberg as a major sugar production area in the late 19th century involved settlers from various backgrounds, particularly German immigrants & communities.