How many disasters must we have, and how much public and private money needs to be spent, before we stop accepting a situation that can and should be avoided?

Professor Mark Adams, landowner at Separation Creek

Introduction

Christmas should be a time of family, rest, and renewal. For the small coastal communities of Wye River and Separation Creek on Victoria’s Great Ocean Road, Christmas Day 2015 brought devastation instead. A fire that had been smouldering in the Otway Ranges for nearly a week surged out of control in hot, windy conditions. By evening, 116 homes had been reduced to ruins. Miraculously, no lives were lost, but the destruction was immense, and the scars still linger.

In the official account, the fire was described as an unavoidable act of nature. The Inspector-General for Emergency Management (IGEM) inquiry concluded:

The rugged terrain, heavy fuels, and forecast weather presented significant challenges to fire suppression. Incident management decisions were appropriate given the circumstances, and community protection was prioritised.

Yet for those with extensive experience in land and fire management, like foresters, fire scientists, and local volunteer firefighters, the official story rings hollow. They contend the Wye River disaster was not an act of God but an act of neglect. It was a small, containable lightning strike that could be extinguished. Instead, it was allowed to burn for days under benign conditions, despite its proximity to roads and towns. When the forecast of bad weather arrived on Christmas Day, the outcome was tragically predictable.

The spark in the Otways

On 19 December 2015, a total fire ban day, a series of lightning storms swept across the Otways. Two small fires started – one in the Great Otways National Park around 4:10 pm and the other in a State forest outside the park around 4 pm. The latter was quickly brought under control and extinguished. The other, known as the Jamieson Track fire, started in rugged yet accessible country just a few kilometres from the Wye River and Separation Creek settlements.

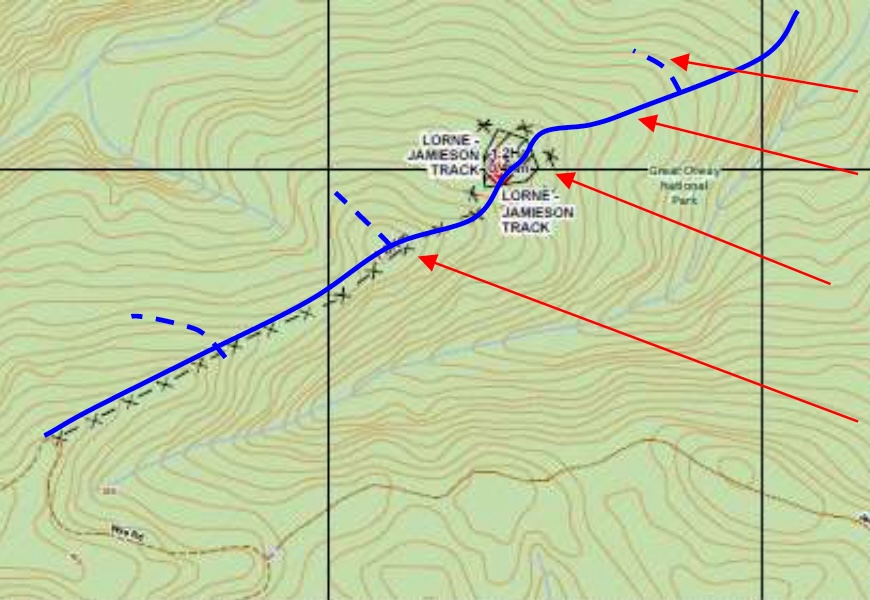

The fire was located on the crest of a long spur halfway along an overgrown fire track, about 1.2 kilometres or a 20-minute walk from Wye Road. An initial small crew of six firefighters arrived at the start of the old track around 5:00 pm, and a fixed-wing aircraft, which had difficulty spotting any flames on the ground and therefore couldn’t estimate flame height. The initial reports described the fire as very small, roughly one hectare in size, with a perimeter of 400 metres. A helitanker was later deployed to drop water on the fire.

The fire crew were told to wait for a dozer to clear the old fire track, even though the first 900 metres was in a drivable condition, which would have allowed them to access the fire with their vehicles and water. The dozer was scheduled to arrive on site at 6 pm. However, around 7 pm, plans changed to a direct attack using hand tools to create a break and contain the fire, aiming to mop up by midday the next day, despite the weather forecast predicting a westerly wind change early the following morning. When this new plan was developed, no one had walked in to assess the fire.

The fire situation reports that night indicated the bulldozer had nearly reached the fire edge by 9 pm at dusk. When the initial attack crew finally arrived at the fire edge, about five hours after ignition on a total fire ban day, they requested permission to attack the small fire by suppressing the edge, but their request was denied. They were not allowed to work on the fire after dark for “safety reasons”.

Instead, they observed the dozer work until midnight. The fire crew then monitored the fire for the rest of the night from the safety of their vehicles on the track. No one evaluated the fire perimeter, so there was little information to allocate resources to the fire the following day. The fire remained uncontained.

When the fire was finally assessed on the ground at 9 am the following day, it was estimated to be 20 hectares! It is unthinkable that this wasn’t done overnight with the crew on site.

No extra personnel were deployed despite the predicted strong wind change, though a couple of dozers arrived. They started building a control line on the western edge of the fire down to Jamieson Creek. Importantly, the exposed eastern flank, with forecast westerly winds, was a wet line in a deep, sheltered gully. At 12:30 pm, a vigorous cold front with westerly winds arrived, and, as expected, the fire escaped over the wet line and spotted in drier fuels along the spur. The fire rapidly expanded to 63 hectares within an hour, although large areas remained unburned due to the sheltered wet fuels in gullies and south-facing slopes.

When rain fell just after 3:30 pm, the aircraft were grounded. The tactic shifted to constructing a six-kilometre dozed controlled line by 10 pm the following day, even though only one kilometre of dozer work was actually needed, as the rest was a wet line created using fuel moisture differentials in tributary gullies.

Over the next five days, the Jamieson Track fire continued to advance gradually. The IGEM report noted that by 21 December, it had burned “approximately 50 hectares.” Weather remained “mild and relatively stable.” Firefighters monitored it, dropped water from aircraft, and lit a back-burn to try to contain its spread. There are suspicions that other bulldozers weren’t accessed due to concerns about the perceived environmental damage from mechanical control line construction.

Critics later questioned why such a small fire, burning under mild weather, wasn’t directly tackled and extinguished. The claim that the terrain prevented more resources from being sent is nonsense, as additional resource allocations were made the day after that excuse was first given.

Disaster strikes on Christmas Day

By Christmas morning, the fire had been burning for six days. Fuel loads in the Otways, after decades of accumulated forest litter and undergrowth, were extreme. The Bureau of Meteorology had forecast hot, windy conditions.

When the winds picked up, the long-anticipated event occurred. The Jamieson Track fire raced towards the coast. Embers showered Wye River and Separation Creek. By late afternoon, flames had engulfed the townships, destroying 116 homes. Families who had gathered for Christmas dinner fled to the beach for safety.

The IGEM inquiry described the outcome as tragic but unavoidable:

Despite the best efforts of fire agencies, the extreme weather conditions on Christmas Day resulted in the fire impacting Wye River and Separation Creek. The response by firefighters was effective in ensuring no lives were lost.

However, for many, this narrative overlooked the central issue of why the fire persisted for almost a week in the first place, when there was ample opportunity to put it out in its early stages while it was still small.

IGEM frames the official narrative

The IGEM was the government-appointed watchdog responsible for investigating the events surrounding this fire. Is it any surprise, then, that it declared the government’s policies and procedures had been applied without any redress?

When the IGEM presented its account of the Wye River fire, the language was calm, clinical, and ultimately exculpatory. The inquiry described a fire fought under challenging conditions from the very beginning and exaggerated the difficulties faced on the fire ground during the first two days. The Otway Ranges, it explained, are rugged, steep, and heavily forested; access is difficult, and crews cannot always reach the fire edge quickly. This natural barrier was portrayed as a major reason for the delay and failure of suppression efforts.

However, retired Victorian foresters in their 70s and 80s inspected the ignition point and found it was an easy walk along a ridge line about 800 metres from a good forestry road. It demonstrates that the public is being misled, as it was hardly a difficult spot. John Nicholson and Denis O’Bryan also carried out separate detailed inspections and analyses of the ignition site to confirm it wasn’t in a rugged, hard-to-reach location. It seems clear that the IGEM used language and descriptions to hide the poor, risk-averse decision-making at the start of the fire, where a direct attack could have been employed overnight to contain the very small fire under favourable weather conditions more aggressively. This was always the approach when the area was previously managed as a state forest.

The report went on to highlight what it called an unavoidable feature of the Otway’s landscape with its heavy, long-unburnt fuels. However, close to the ignition point, there is hardly any evidence of that description. The fuel loads elsewhere may have been different due to decades without fire, which had allowed leaf litter, fallen branches, and thick undergrowth to build up, creating the conditions for extreme fire behaviour once severe fire weather arrived. When the Jamieson Track fire finally broke out on Christmas Day, the flames were able to run with such ferocity, the report suggested, because of these massive fuel loads.

An example of misinformation in the IGEM report is the claim that the fire was burning in heavy fuels across tall stringybark country, suggesting that spotting activity would overwhelm any efforts to establish a firebreak by hand. However, the forests where the fire started were blue gum and messmate country, not stringybark.

Overlaying these challenges, the inquiry highlighted the weather. Hot, dry winds swept across Victoria on Christmas Day, creating what fire managers fear most: a small blaze in heavy fuels meeting the perfect storm of conditions. In this context, the fire’s expansion into Wye River and Separation Creek was not due to poor planning or delay but to nature’s brutal inevitability.

Finally, the IGEM narrative sought to reassure the public that decision-making was sound and well-considered. Firefighters and managers, it asserted, had done everything they could with the information at hand. Their priority was the safety of firefighters and the protection of the community. The absence of any fatalities was regarded as the ultimate proof of the strategy’s success. Controlling the fire is no longer seen as the sole measure of success.

In weaving together these elements of rugged terrain, excessive fuels, severe weather, and a calm, rational response, the inquiry effectively dismissed human agency in the disaster. What occurred at Wye River was depicted as an unavoidable result of natural forces rather than the outcome of decisions made in the critical days leading up to Christmas.

A fire that should never have developed into an inferno

Not everyone accepted the official account of the events. Many critics viewed the Christmas Day disaster at Wye River not as an unavoidable act of nature but as a failure of management. They argued here, here, here, here, here, here and here that the Jamieson Track fire smouldered for days in the Otways, largely unchecked, until worsening weather allowed it to escape. In their view, the destruction of more than a hundred homes was not caused by steep terrain or dry winds, but by a decision not to extinguish a manageable fire when the opportunity was available.

The Otways region is no stranger to fire, nor is the town of Wye River. Critics highlighted that long-unburnt forests tend to fuel fierce blazes, yet little had been done to reduce those risks near communities. Prescribed burning, they claimed, had been neglected for years, leaving settlements like Wye River surrounded by dense fuels. When the Jamieson Track fire ignited, it was always likely to threaten the town; the only question was when.

In a leaked entry from a Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning burn journal dated March 2014, Environment Minister Lisa Neville intervened to stop a planned control burn near Wye River on 27 March 2014 due to concerns about koalas. The note states:

Minister Lisa Nevill [sic] – not to burn Wye River next week due to koalas being a hot topic in the media.

The critics also challenged the idea that firefighting crews were powerless against the blaze. Several days of relatively mild weather before Christmas offered critics what they saw as a perfect chance for a direct attack and containment. Instead, the fire was allowed to burn, seen as a low-priority incident in a remote area. By the time weather conditions worsened, it was too late. In this view, the failure was not due to the terrain or conditions but to a risk-averse culture in fire management that preferred waiting and watching over taking decisive action.

Supporters of the official story argued that the Otways were too rugged, the fuels too heavy, and the weather too fierce for any other outcome. However, critics pointed out that these claims fall apart under scrutiny: the terrain was challenging but manageable, the weather was mild for six days before Christmas, and the heavy fuels were the result of years of neglect. What authorities claimed was unavoidable was actually due to hesitation and misplaced priorities.

One of the biggest mistakes in firefighting is not launching an immediate, forceful attack when the fire is at its smallest.

Victoria’s former chief fire officer, Rod Incoll, explained what was typically done for similar fires when he worked in the Otways. Crews would carry out a thorough first attack and had the confidence to contain the fire within one to three days, even on a small budget, without relying on costly aerial water bombing.

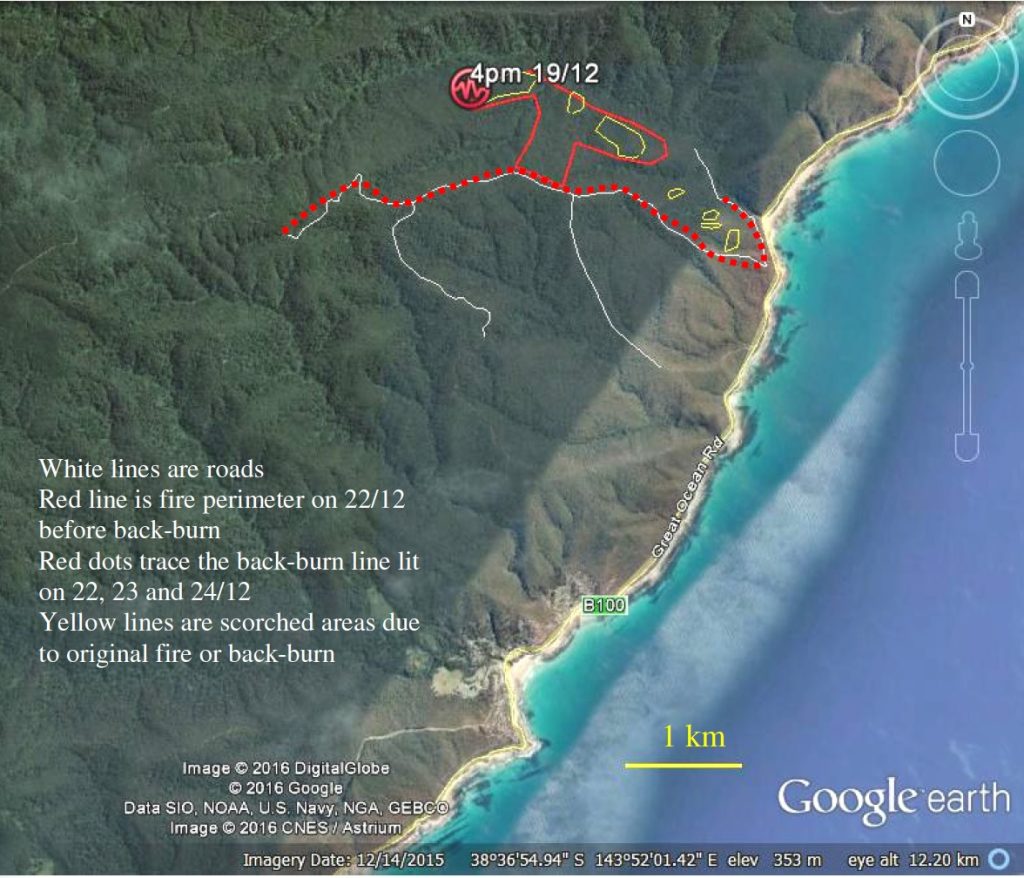

There was also significant discussion about the ill-timed backburn carried out on Jamieson Track to the coast on 22 December. Apparently, it was delayed because of the need to obtain Ministerial permission before lighting. This highlights the centralised, arms-length decision-making that sidelines on-site fire controllers, who are in the best position to determine the most effective containment and control strategies.

As a result, the control approach shifted from constructing a six-kilometre control line to contain the fire with a direct attack involving three bulldozers to an indirect method using a backburn just two days before the forecast severe fire weather. This adjustment changed the fire from a narrow front of a few hundred metres near Jamieson Track to over 4 kilometres, with forecast northerly winds expected later in the week.

Back burns can be an effective firefighting strategy, but their success isn’t solely determined by how deeply they penetrate. Emergency Services Commissioner Craig Lapsley regarded the Jamieson Track back burn as successful because it burned into the fuel at depth, creating a sufficient break. However, this overlooks the equally vital tasks of resourcing patrols and conducting mop-up operations on the lit edge. Unless hotspots are fully extinguished, smouldering logs and stumps can send embers across the break into unburnt fuels, effectively making the back burn ineffective and forcing firefighters to fall back to another containment line.

Official records show that only limited resources were allocated to patrol and mop-up activities on Christmas Day, a poor fire weather day. This shortfall caused seasoned observers to wonder whether the back burn might have actually increased the danger to Wye River and Separation Creek. IGEM dismissed these concerns, repeating Situation Reports without providing any independent or critical analysis.

While firefighting authorities claimed the backburn was successful, all we know is that at 11 am on Christmas morning, spot fires were reported south of Jamieson Track, and field reports raised doubts about whether the fire could be contained. A new strategy was quickly devised to focus on air attack to slow the fire’s spread, which now had a free run to the two settlements in its path, and to prepare for evacuation. By 12:45, the focus shifted to asset protection.

It is clear to any reasonable person that choosing to back burn was a key factor in the fire spreading southwards to Wye River and Separation Creek when it wasn’t properly monitored. This is supported by the fact that the fire breached Jamieson Track at various points and times. By 15:10 on Christmas Day, houses in Mitchell Grove at Separation Creek had been impacted by the fire. Local firefighters say only a small number of CFA crews were sent to these areas when needed because their leaders believed it was too dangerous. However, IGEM’s report shows a different story, praising the fire control team for their procedural response.

Underlying these criticisms is a broader frustration with how bushfire agencies present their failures. Inexplicably, Lapsley tried to describe the fire as being in a “deep gorge,” attempting to blame the terrain and weather for the lost back burn. Critics argued that blaming the terrain, the fuels, or the weather shifts the focus away from decisions made by those in responsible positions. Wye River was not an unavoidable victim of the Christmas Day weather; it was a town that could have been spared if the fire had been extinguished earlier.

Accountability denied

In January 2016, the Victorian Coroners Court announced it would investigate the fire because it was in the public interest. However, more than 18 months later, the coroner, Judge Sarah Hinchey, decided not to hold a public inquest, stating that one was not necessary because:

There is already sufficient evidence about the fire’s cause and spread” and “there is no legitimate coronial purpose that is likely to be served by holding a public hearing in this matter.

By choosing not to hold an inquest, the coroner removed the only chance for an independent review of how the fire was managed, ensuring those responsible avoided the scrutiny they deserved.

The Victorian Coroner’s handling of the Wye River fire was essentially just a rubber stamp on the Inspector-General of Emergency Management’s politicised review. By stating there was already “sufficient evidence” and refusing to hold a public inquest, the coroner heavily depended on IGEM’s account and the testimony of Lapsley. Essentially, the one forum capable of providing independent scrutiny was shut down, protecting the reputations of government agencies and senior officials rather than testing them.

That decision left serious contradictions unexplored. Firefighters on the ground argued that the terrain wasn’t too steep, pointing to an old spur track that could have been reopened for vehicle access. Crews were willing to tackle the fire directly on the first night, when conditions had eased, but were overruled by distant managers who overstated the location’s difficulty and the fuel hazard. Weather records clearly disprove the claim that suppression was impossible on the day of ignition. Still, none of these issues were publicly discussed, and no independent analysis was done. The refusal to hold an inquest robbed the community of its right to answers and made sure that no one in authority would be held responsible for a disaster that could, and should have been, prevented.

A pattern of avoidable disasters

The tragedy at Wye River wasn’t an isolated incident. It reflects a worrying pattern of bushfire disasters across Australia, where small, manageable ignitions are allowed to smoulder until they escalate under harsh conditions. Each time, the same excuses are made, such as rugged terrain, extreme weather, and heavy fuel loads. However, when looked at collectively, these fires expose a systemic hesitation to intervene early and a bureaucratic culture that prioritises process over results.

The 2003 Canberra fires are still a well-known example. A cluster of lightning strikes smouldered in the Brindabella Ranges for over a week before spreading into the suburbs during a spell of severe weather. Authorities had multiple chances to put out the fires while they were still small and manageable, but they chose to wait. When the wind change became unavoidable, four people lost their lives and nearly 500 homes were destroyed.

A decade later, the 2013 Wambelong fire in western New South Wales followed a similar pattern. A blaze that began in Warrumbungle National Park under relatively mild conditions was not contained when firefighters were allowed to go home at nightfall, despite repeated warnings from local firefighters who knew the terrain and recognised the danger. When a decision was made to carry out a back burn the next day during a total fire ban, the fire quickly spread into surrounding farmland, destroying homes, stock, and livelihoods. Once again, official reviews emphasised the extreme conditions rather than the failure to contain the fire on the first night, when it was still small.

The 2018 fire at Tathra on the New South Wales south coast followed the same pattern. A blaze that started on the outskirts of town was allowed to grow unchecked. Meanwhile, disputes simmered between Rural Fire Service command and professional Fire and Rescue brigades over jurisdiction and tactics. The result was sadly predictable, with more than 60 homes lost and a community left shattered. Later that year, the Yankees Gap fire in the Bega Valley told a similar story of bureaucratic inertia.

Each of these disasters, like the Wye River fire, was later portrayed as unavoidable — the tragic cost of living in a dry, fire-prone landscape. However, critics argue the pattern shows a different story. They see in these events the marks of a risk-averse bureaucracy reluctant to take responsibility for decisive suppression efforts, instead blaming nature’s fury. In doing so, the authorities protect themselves from accountability, while communities bear the brunt.

In each case, the recurring pattern involves failing to address small ignitions, bureaucratic deadlock, and investigations that blame nature rather than the decisions made.

Denis O’Bryan quite rightly points out that the Wye River fire clearly demonstrates:

The dichotomy between what people wanted (i.e. no house loss) and what the government wanted – a high priority to defend its actions in the media, to secure people’s obedience for evacuation and reconstruction policies, and to promote its concept of resilience after disasters.

Sadly, bushfire protection often depends more on government spin. Framing this fire as narrowly avoiding a disaster caused by Mother Nature, and suggesting it could have been much worse, while implying the outcome was out of their hands, only shows that Australians can expect more calamities.

David Packham and Tim Malseed believe the media share the blame for the issues impacting contemporary firefighting.

In the days that follow each and every bushfire disaster, the media also stakes its claim to a share of the blame. Largely ignorant of the ways of forest fires, unschooled in fighting them and prone to parrot green nostrums and nonsense, reporters become at best stenographers and, almost as often, cheer squads for the same politicians they should be calling to account.

The template for stories is as shallow as it is familiar: confused and distraught victims, people who have lost homes and kin, are pressed to find the upbeat side of avoidable tragedies. They are prompted to speak of community spirit, our brave firefighters and individual acts of heroism. Meanwhile, questions about politicians’ responsibility go largely unasked. And when they are raised, they are ridiculed as manifestations of “the blame game” — as if there was no blame whatsoever to be apportioned!

The politics of fire

At the heart of these failures is the influence of green politics and bureaucratic culture. As the Timberbiz piece stated:

Foresters who once carried the knowledge and the bulldozers are gone. Instead, we have a conservation ideology that values untouched parks over safe communities.

Professor Mark Adam’s family built their holiday house at Separation Creek. While it survived the fire, he still hopes each year that at least once, a fuel reduction burn will be carried out in the forests along their vulnerable northern and western edges.

Instead, because of inaction, governments have become adept at shifting responsibility. Premier Daniel Andrews dismissed suggestions that improved fuel reduction could have made a difference at Wye River, calling it a “simplistic” view. However, his own Emergency Services Commissioner had earlier acknowledged that fuel loads directly affected fire intensity.

For some inexplicable reason, the Incident Control Team did nothing from 21 December to organise the defence of Wey River and Separation Creek settlements in case they couldn’t contain the fire. It was left until well into Christmas Day, just hours before the fire hit the town, when the only option available was to issue an evacuation order.

Dismantling the excuses

The official explanations for the Wye River fire rely on familiar reasons. They mention the tough Otway terrain, the buildup of fuels, and the weather on Christmas Day. Yet, upon closer look, these claims fall apart, exposing incompetence.

As John Nicholson rightly asks:

Was the fire considered inaccessible if it could not be encircled by a bulldozer and tankers?

Yes, the Otways are steep and heavily forested, but they are not unique in that regard. Across Australia, firefighters have successfully carried out aggressive suppression efforts in much tougher terrain. Helicopters, bulldozers, and backburning strategies are well known to Victorian fire managers. The idea that this fire was “too hard” to attack strains credence, especially considering the mild conditions in the days before Christmas. During those times, crews could have worked hard to contain the blaze. That chance was missed, not because the terrain made it impossible, but because the will to take the risk was lacking.

The issue of fuel is just as irrelevant. Everyone knew that the forests around Wye River had long remained unburnt, and everyone understood what that signified during a hot, dry summer. If anything, this should have strengthened the resolve to extinguish the Jamieson Track fire before it could spread. Instead, the state of the fuels was later used as an excuse, as if their presence were an unavoidable force of nature rather than the clear result of years of neglectful management. Hazard reduction on Crown land is a responsibility of the government, and its neglect cannot be spun as a simple excuse.

And then there was the weather. Indeed, the hot, dry winds of Christmas Day played their part. But extreme fire weather is not surprising in Victoria in late December. It’s a certainty. To treat it as the main cause of the disaster misses the point. The Jamieson Track fire should never have lasted long enough to meet that weather. Once again, critics argue, the fire’s duration was a management decision, not a natural inevitability.

The final pillar of the official story—that decisions were sound because firefighter safety and community protection were prioritised—is the hardest to accept. Of course, firefighter safety must come first, and no one advocates reckless risk-taking. However, this principle is often used as a shield against scrutiny too often. It lets agencies portray inaction as prudence and retreat as wisdom.

Meanwhile, communities like Wye River bear the brunt of the consequences. The destruction of more than a hundred homes was hardly an act of “community protection.” Instead, it was the predictable result of a strategy that failed to extinguish the fire while conditions remained favourable. Firefighter safety is rarely compromised when a fire is small and burning during relatively calm weather.

When the excuses are stripped away, what remains is stark. This was not an uncontrollable act of nature, but a small fire left to smoulder until it could no longer be managed. Terrain, fuels, and weather may have influenced the conditions, but it was human decisions and indecisions that sealed Wye River’s fate.

A culture of unaccountability

The tragedy at Wye River should have been a wake-up call. Instead, it became just another case in the growing list of fires where inquiries protect institutions rather than the communities they serve.

No bureaucrat lost their job. No politician took responsibility. Instead, residents were told to accept their fate as the cost of living in a fire-prone landscape.

The reality is more brutal because the fire was not unavoidable. It stemmed from choices. Choices to prioritise park values over community safety, choices to neglect fuel reduction, choices to avoid aggressive initial attack, and choices to protect bureaucratic reputations instead of facing uncomfortable truths.

Until this culture of unaccountability is addressed, Australia will continue to face preventable bushfire disasters. Wye River was not an act of God; it was an act of human neglect, and because these lessons are ignored, we see similar disasters happening again.

In summary, we have gone a long way in the wrong direction since CFA officer, Stephen Petris, under the guidance of John Nicholson, prepared a report on the response to major fires between 1939 and 1994 and outlined the standard procedure in the country at the time was:

An effective suppression strategy when weather and fuel conditions are conducive to a major conflagration is to extinguish outbreaks of fire quickly, before they become too intense to control.

Excellent article. And I don’t think it’s a case of being wise in hindsight.

Why decision makers are risk-averse, in this case, not launching an aggressive suppression effort when the fire was small, is multi-factorial.

In addition to the points raised by Robert, inexperienced leadership in firefighting may have fed the risk aversion.

Thanks for this detailed explanation Robert. Sad reading.

We should all hope that change brings accountability, before the shared knowledge of living with fire among foresters and bushmen and women is lost over time.

In 1968 I was a forester in far north NSW. We had no reliable 2-way radios or mobile phones. We had trust in our small one- and two-man forestry gangs. When they detected a fire, they got someone to phone the office, and they got on with it. They chipped fire breaks with McLeod tools and, if a back burn was necessary, lit it.

I can remember chipping McLeod tool breaks at night by the light of the fire we were containing. You started where the fire began and gradually pinched it out, making sure all the fuel was burnt on the fire side of the break. Then you mopped up, which involved ensuring nothing was burning or smouldering within 20 metres of the edge.

One employee near retirement age was an expert. He carried a bucket of water, not a knapsack. If he could pick it up, he dunked it. Otherwise, he sparingly poured the water to ensure it was really out and not hissing. When he said his sector was safe, there was never any question.

If this approach had been used on the “Jamieson Track” fire, it could have been declared safe on that first night.

We need to have faith in our first responders to get on with it without requiring approval from remote superiors.

Sure, there may have been storms about that day, but where, and when it started, it could just as easily have been lit by someone who thought “it needed a bit of a burn”. The arsonist may even have been the person who first reported it.

Once again, was this the result of “benign neglect”?

Well done Robert.

The genesis of over-the-top risk-averse fire-fighting in Victoria appears to be the Linton fire tragedy of 1998, where five CFA fire-fighters were killed while attending a forest fire in unfamiliar territory far from their home base. Wikipedia describes the ‘Linton fire tragedy’ as “marking the beginning of a new era of fire-fighter safety”.

A very painful, months-long Coronial Inquest found that these volunteer fire-fighters inadvertently drove their tanker down an overgrown bush track into the teeth of a fire whipped-up by strong winds and were unable to turn-around before being overwhelmed.

Understandably, no fire agency or bureaucracy would want to revisit such an inquiry, and so it heralded-in new protocols that prioritise fire-fighter safety over and above all else, including the need to quickly contain fires to small size where-ever possible, even though it is patently obvious that risks to fire-fighters and the broader community are minimised when fires are prevented from becoming large and uncontrollable. Unfortunately, these priorities and risk averse protocols typically constrain the capability to quickly suppress fires.

In reality, fire-fighter safety has always been a very high priority. But fire-fighting was traditionally conducted by an experienced workforce able to take calculated risks to safely achieve quick suppression when opportunities arose. Such opportunities are now often being lost, not least because fire fighting experience has also declined.

An interesting footnote to the Wye River fire was that the then IFA’s Victorian Division call for a public inquiry into the fire-fighting strategy was reported on the front page of The Age newspaper several days after the Wye River and Separation Creek communities had been decimated. The Division Chair at the time, Gary Featherston, had signed the IFA’s media release. Within days, Gary’s permanent part-time job at the Australasian Fire and Emergency Services Authorities Council (AFAC) had been forcibly terminated at the direction of Victoria’s most senior emergency services bureaucrat, arguably in accordance with a political directive to silence critics. Sadly, the state Labor Government which orchestrated such a Soviet-style attack against freedom of speech remains in power today, albeit with a different leader.