The aviator who dreamed of an island

Sir Reginald Barnewall was a man of the air long before he ever set eyes on Fraser Island. He was born into a wealthy Victorian grazing family whose history went back to the Norman conquest. A baronet, he carried himself with the confidence of privilege but also with the restless ambition of a man who wanted more than land and cattle. Flying was his passion. During World War II, he served in Papua New Guinea with the Royal Australian Engineers, attached to the Allied Intelligence Bureau – the forerunner to Z Force.

His job was both dangerous and technical, involving the handling and destruction of high explosives. He also had a single wartime encounter with Fraser Island, a brief visit to the western shore near McKenzie’s Jetty. It left no mark on him. He described the place in his memoirs as:

A brooding vastness, and its myriads of gigantic, voracious and ubiquitous sandflies.

After the war, Barnewall built an aviation career. He flew with Mandated Airlines across the mountains and jungles of New Guinea, sharpening the bush-flying skills that would shape his life. In 1954, back in Australia, he established Goulburn Valley Air Services, connecting regional Victoria and Tasmania with King and Flinders Islands. Regular flights to Hervey Bay to visit his parents – who had bought a house there in 1956 – brought him close to Fraser Island, but at that time it was merely a sandy shape across the strait.

It was only after a spell in Samoa that Fraser Island started to appear vividly in his mind. In 1958, he and his first wife moved to Apia, where he established Polynesian Airlines. There, he experienced the influence of tropical tourism firsthand. Pan American Airways was then creating resorts across the Pacific, and Barnewall was caught up in the allure and opportunities of it all. Samoa provided him with both a blueprint and a longing. If remote islands in the Pacific could become popular spots, why not Fraser Island?

When his father died in 1961, Barnewall returned to Australia to manage the family properties. But he never lost sight of his dream. He bought a Cessna 182 and flew charters in Victoria under the name Eildon Aviation. When he travelled north to Queensland to visit his mother, he often detoured low over Fraser Island. From the air, it looked impressive, but it wasn’t until he stood on the sand that the island truly captivated him.

Discovering El Dorado

The turning point arrived in 1964. Twenty years after his dusty wartime visit, Barnewall returned to Fraser Island. This time, instead of swatting sandflies, he navigated the outcrops of Middle Rocks and stepped onto the vast expanse of sandy beach north of Waddy Point. What he saw overwhelmed him with awe.

I believe that was the pregnant moment of conception of my long-enduring love affair with this northern part of Fraser Island … I beheld for the first time at ground observer’s eye level the expansive northerly sweeping vista of sea, sky, sand and shoreline solitude. It literally took my breath away. Instantly, I knew I was hooked; here, right before me, lay my El Dorado; my dreamland.

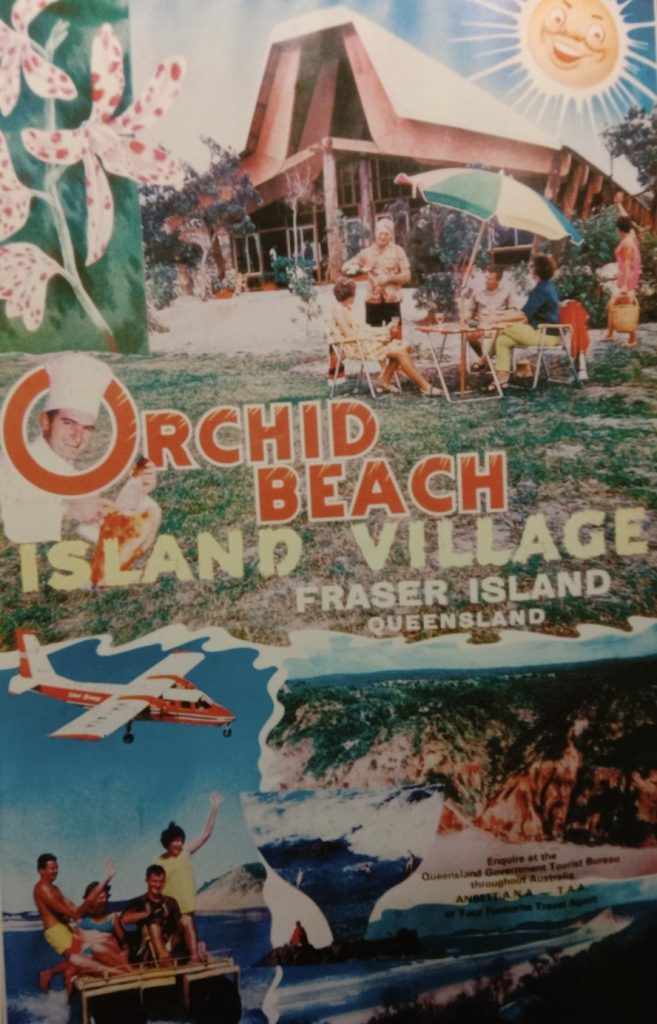

That vision shaped his plans. He intended to build a resort there, a place where guests could arrive by light aircraft, step directly onto the beach, and enjoy a “pristine wilderness” with all the comforts of a holiday.

Barnewall began by scouting the land from the air, looking for flat ground near the beach where an airstrip could be built. He was drawn to the stretch between Ocean Lake and Waddy Point, a spot already loved by fishermen. It had the remoteness he desired, the proximity to good fishing spots, and the beauty to inspire tourists.

Government policy at the time appeared to support his ambitions. In 1962, the Queensland government reclaimed a mile-wide strip of state forest land between Eurong and Happy Valley for tourism development, returning it to Crown land, and the following year, extended the claim all the way north to Sandy Cape. It was the opening Barnewall needed.

He wasn’t alone in his vision. Another aviation enthusiast, Don Adams – a former Childers cane farmer – was also considering the Waddy Point area for an airstrip. The government made it clear it would only support one proposal. Barnewall would need to act quickly and decisively.

Building a resort in the sand

After a few reconnaissance trips to the island to make sure his airstrip location would work, in January 1965, he moved to Hervey Bay, selling up the family’s grazing interests in Victoria, which included the property Crickstown in the Central Highlands of Victoria.

Fraser Island in the 1960s was a long way from the conveniences we have today. There were no barges with hydraulic cranes, hardly any roads and no infrastructure. Building anything substantial meant improvising. The beach was unnamed, and Barnewall named his chosen spot “Orchid Beach” after the blotched hyacinth orchids he spotted blooming in the sand. They are tall stems with pink flowers stained red, growing stubbornly in the coastal environment. Like the orchid, his resort would need resilience to thrive.

To provide quick access to the island, Barnewall needed a suitable airstrip at Hervey Bay. Even though an airport existed at Urangan, it was primitive, too rough for regular landings, miles from anywhere, hard to reach and didn’t provide any security for parked aircraft.

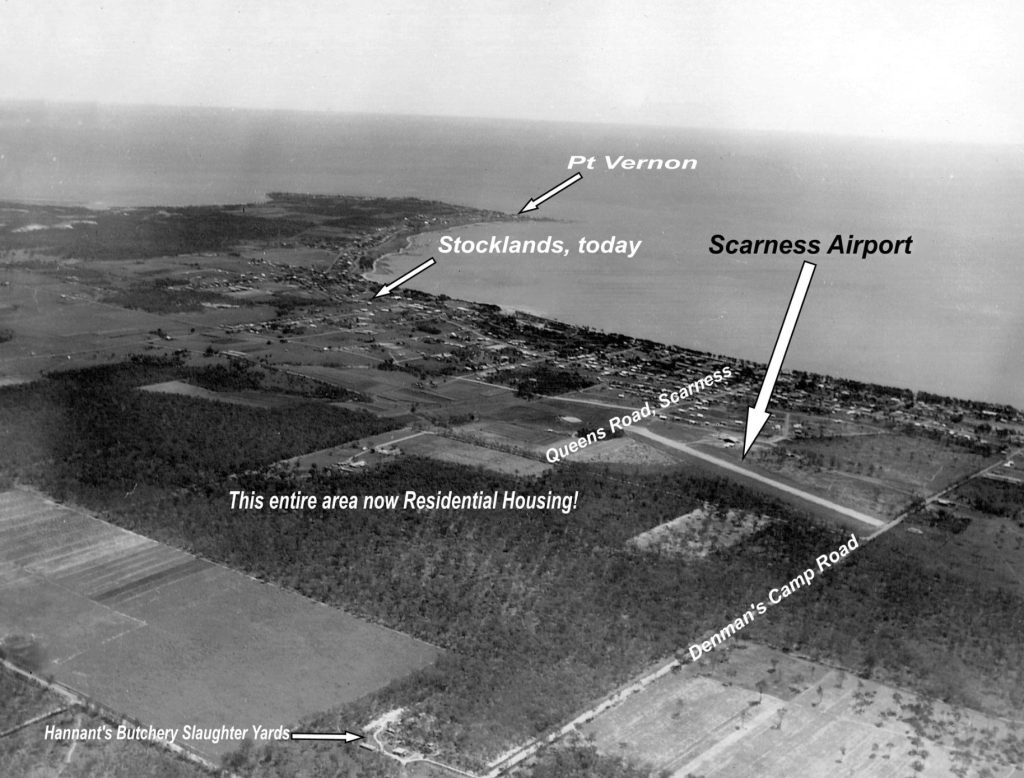

In February 1965, Barnewall bought 60 acres of land at Scarness Heights to build an airport behind Scarness and provided air charters to Fraser Island. The airstrip ran adjacent to Boat Harbour Drive between Hillcrest Avenue and now Frangipanni Avenue, and Denmans Camp Road and just past Queens Road. Adams and Barnewall formed a charter airline partnership, calling it Island Airways, to operate out of the Scarness airstrip, taking guests to the island.

Trials and tribulations building the resort

Things moved quickly. He met many people willing to help him achieve his dream, including Jack Pashley, Donnie Tyndall and Percy Wiedon. But only two people could get his building materials to Orchid Beach: timber cutter Joe Cunningham and Sid Melksham.

Having them work for him was a bit of a shock to poor Barnewall, who was used to being treated with great respect.

Barnewall first decided to build two rudimentary huts to provide self-catering accommodation to fishermen and Melksham agreed to transport the materials from Maryborough, across the Great Sandy Strait to Wathumba Creek, to then be hauled overland to Orchid Beach.

Melksham bought a second-hand 60-foot wooden trawler, but it was a cruiser, not a cargo barge. Without a derrick or crane, every heavy load had to be broken down into manageable pieces and carried aboard by hand.

The first trip did not start well. Barnewall had ordered pre-cut timber planks, each weighing half a tonne, from Hynes sawmill. When Melksham went to load them, he found they had been strapped tightly into a bundle, a far bigger bundle than he could manhandle onto the trawler.

It took Melksham ages, with a bit of finger-biting and foul language, to cut off the strapping, split them up piece by piece and then load the planks by hand onto the boat. This delayed the voyage by two days and missed the crucial spring tide. Such setbacks were common.

It was a long haul, and Melksham had to work the tides. When he finally reached Wathumba Creek, he was running late and had to unload quickly to catch the tide back to Maryborough. Barnewall and a couple of chaps were waiting for him with a small truck. It was a sloping beach, so Melksham had to moor out, and the Orchid Beach trio had to form a line out to the boat to pass the planks to the shore.

Barnewall, being the tallest, had to stand out in the deepest water to be confronted with, as he described:

This giant of a man passing planks of wood at me at high speed, far faster than I could pass them along. I had never heard such language in my life, as he kept urging me to hurry up so he could catch the tide home. We piled all the planks on the beach ready to load them on the truck, while he just took off in a hurry. We were still loading up into the night.

Melksham got appendicitis in the middle of all these back-and-forth trips to Wathumba and had to go to hospital. He got his mate Jack Pashley to skipper the trawler for him but forgot to foreworn Pashley about the quality of help he would get from Barnewall and his workers. Barnewall recalled:

I thought Sid’s language was bad enough, but that was before Jack started shouting at me to hurry up.

Subsequent trips were no more successful until Melksham approached Barnewall and, to the latter’s relief, suggested he use his own trucks and blokes to get the materials from the boat to the resort site, which proved more successful.

However, getting the big generators to Orchid Beach was a different story. They were too big and heavy to be manhandled on and off the trawler. Melksham had them loaded on his truck and drove up the island surf beach with Max Williams as a helper.

All went well until they came to Middle Rock, which at the time was called the goat track and was really rough and rocky, with a sharp dogleg halfway up.

Melksham set off in low gear up the track, but there was no way he could get the heavily laden truck around the dog leg without island ingenuity. Mleksham got Williams to hop out and throw rocks at the front wheels to turn them. They made it to Orchid Beach, still shaking with nerves at their experience.

Barnewall asked timber cutter Joe Cunningham to supply him with big satinay logs with the bark on for the portico of the fale fono. Cunningham and Melksham chained the two massive logs to Cunningham’s truck and got them up Middle Rock in the same manner.

Barnewall, with absolutely no understanding of the effort it had taken, came out to look at his logs. He found some of the bark had been rubbed off one and complained bitterly to Cunningham.

Well, that did it – poor Barnewall got another ear-bashing of language he had never heard before.

The resort takes shape

Despite the significant challenges of getting materials on-site, by Christmas 1965, the first huts were finally completed. Inspired by Samoan fales, they were simple open-sided shelters with cooking facilities, intended for self-catering groups of fishermen.

The following year, Barnewall decided to advance his grand plans and move from the small self-catering units to a larger resort. This meant Barnewall wanted out of the airline’s business and set up a separate company, Orchid Beach (Fraser Island) P/L, to run the resort.

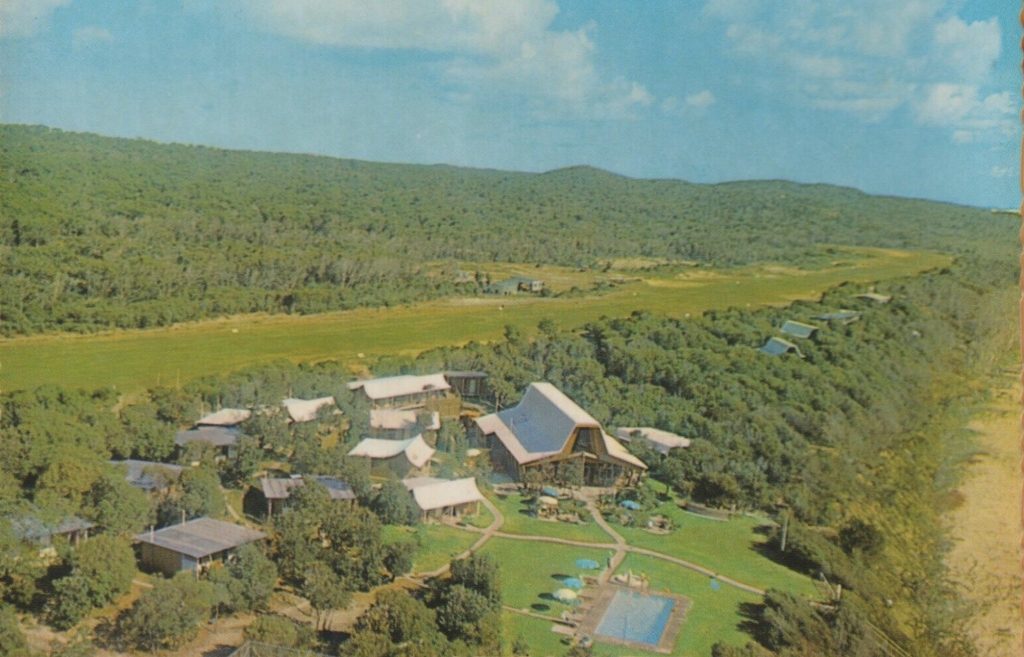

The enterprise expanded. Barnewall constructed the Angler’s Lodge—accommodating eight people—and even added a swimming pool overlooking the beach, an adventurous luxury in such a remote location. He imagined a whole village of Polynesian-inspired buildings, including a central “fono fale” to serve as a dining area and bar, surrounded by huts and bungalows, all set against the vast backdrop of ocean and dunes. Orchid Beach Resort officially opened in June 1969. For a short while, it seemed as if Fraser Island had its own tropical retreat.

The new resort received a timely boost in business after Cyclone Ada struck the Whitsunday Island resorts in January 1970. Many holidaymakers were rebooked into Orchid Beach by travel agents. Within 24 hours of the disaster, bookings increased by 25 per cent for the following two months, and further rises were anticipated. They secured a significant share of the Hayman Island bookings.

The beginning couldn’t be better for Barnewall’s dream.

The storm years

Unfortunately, Barnewall lacked experience with coastal formations, and he did not seek professional advice. One day, he walked Melksham out to look at his view from the top of the exposed foredune and proudly asked what Melksham thought of it. Melksham shook his head and pointed out to sea to the wrecked remains of the Marloo and said:

The Marloo was washed ashore. Now it is about half a mile out to sea. The Marloo hasn’t shifted, but the cliffs have eroded that far back.

Sure enough, as Barnewall found out the hard way, nature had its own plans. Fraser Island lies squarely in the path of tropical cyclones, and in the early years after the resort was completed, they came with brutal regularity.

Cyclone Edith brushed the island in early 1967, causing minor damage. But in January 1967, Cyclone Dinah roared down from the north as a Category 4 monster. Winds of 200 kilometres an hour ripped through Orchid Beach, tearing roofs from buildings, flattening vegetation, and ruining the settlement’s well. Barnewall, who had seen storms in Samoa, said no cyclone he endured in the Pacific:

Held a candle to what Dinah was dishing out to us that day.

The punishment didn’t stop. Cyclone Dora in 1971 stripped fifty metres from the foredune. Daisy followed in 1972 with 160-kilometre winds. Then came Wanda, Pam, and Zoe – three cyclones in three months in 1974. Wanda alone dumped a metre of rain in two days. Each storm carved away more of the beach, battered the buildings, and tested the patience of staff and guests.

The showpiece swimming pool, perched at the edge of the dune with a panoramic view, became a symbol of the resort’s fragility. As erosion ate into the sand, the pool was left hanging precariously over the edge. For a year, it clung there, a bizarre sight, before finally collapsing onto the beach below.

The cyclones coincided with a shift in politics. In 1971, the government declared a national park in the northern part of Fraser Island, wrapping around Orchid Beach. Environmentalists were beginning to rally against large-scale development. Barnewall, caught between natural forces and political ones, was losing ground.

Decline and disputes

By this time, Barnewall had had enough. The resort had never delivered the financial success he had hoped for. He sold to a syndicate around 1972–73. But the new owners fared no better. Mismanagement set in almost immediately. Children tobogganed down the steep banks of the foredune beside the steps, gouging out scars that hastened erosion. Maintenance lapsed. The dream began to fade.

Enter Snow Richards, a Toowoomba entrepreneur with aviation interests. He took over Island Airways in 1975 and acquired the Orchid Beach lease. Richards saw opportunity in land. In 1969, Barnewall had arranged for the first option on the only freehold land – a 160-acre block at Wathumba, but never exercised it. Richards did, and then engineered a swap with the government, trading the swampy, mosquito-ridden Wathumba block for nearly 70 hectares of prime land adjoining Orchid Beach. It was a shrewd move that angered environmentalists, who saw it as a sweetheart deal.

From there, a bitter struggle unfolded. The Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO), led by John Sinclair, fought every rezoning application in the courts. Every time the Hervey Bay Council approved developments, FIDO appealed. Minister for Local Government, Russell Hinze, intervened with ministerial rezonings. Allegations of political favouritism swirled. The courts oscillated between dismissals and upholding objections. Orchid Beach became as much a battleground of lawyers as of bulldozers.

Island Airways, weighed down by debts and legal costs, was wound up in the early 1980s. Once again, Orchid Beach was sold, this time to a Brisbane car dealer, Keith Leach.

Reinvention: the fishing years

Leach understood something his predecessors hadn’t. Fraser Island’s strongest asset wasn’t swimming pools or Polynesian fales – it was fishing. The island’s surf gutters and estuaries teemed with tailor, whiting, and bream, drawing anglers from across the state and the country.

In 1984, Leach launched the Fraser Island Fishing Expo. The first event attracted just over 100 entrants and offered $10,000 in prize money. Strong winds marred the opening days, but the fish were biting, and the concept was sound. Within two years, the Expo had 800 competitors. In 1986, Toyota came on board as a major sponsor, and the Expo exploded in scale. With prizes including new four-wheel drives – perfect for Fraser’s sandy tracks – the event became the richest fishing competition in the southern hemisphere.

The Expo breathed new life into Orchid Beach, filling the bar and dining room each May. It created a festive atmosphere that echoed across the island and drew national attention. For a time, it seemed Leach had found the formula to keep Orchid Beach afloat.

Politics and closure

But the tide was turning. In 1989, the newly elected Goss Labor government established an Inquiry into Fraser Island’s land use as per the pre-election promise. Its 1991 report recommended stronger preservation, emphasising preservation over development. The following year, the island was inscribed on the World Heritage List.

The new status was a death sentence for Orchid Beach Resort. Its airstrip was closed, cutting off the quick access that had been its lifeline. Environmentalists pushed relentlessly against its continued operation, and government officials saw it as incompatible with World Heritage values.

In 1993, the government quietly purchased the resort for $6 million – a sum that raised eyebrows given the property’s dilapidated state and poor viability. Two years later, in 1995, the bulldozers moved in. The last trace of Sir Reginald Barnewall’s dream was reduced to rubble.

The Fishing Expo survived, but by then it had been relocated to the Orchid Beach settlement itself.

Epilogue: a paradise lost

Today, Orchid Beach is no longer a resort, but a settlement of shacks and houses tucked behind the dunes. It is now the largest settlement on the island. Fishermen still launch from its beaches, families and holidaymakers still visit, and the name lives on. But the resort is gone, swept away by storms, politics, and shifting tides of history.

Sir Reginald Barnewall’s vision was flawed, perhaps doomed from the start. Yet it was also audacious. He imagined something no one else had. He believed that Fraser Island’s wild north could host a resort to rival the Pacific. For a brief, shining moment, Orchid Beach seemed to prove him right. Then the sand shifted, the waves rose, and paradise slipped away.

When Barnewall sold his island dream, he bought an avocado farm on Mount Tamborine in the Gold Coast hinterland.

With all the stresses of developing on Fraser Island behind them, Sir Reg and Sid became close friends. After Sid retired on the Gold Coast, they met up at least once a month for Sunday lunches.

Sir Reg died in 2018.

Just finished reading your book Paradise Preserved Robert, a great and easy read. Now planning a trip to the island with your book in hand and also now the Orchid Beach Resort tales to follow up on.

Question – When would be the best time to visit re least busiest?

Malcolm, the least busiest, is in winter or late November and December, before the holiday season. If you don’t mind the cooler nights if camping, winter is best.

I take a group of guys over each August when the Taylor fishing is on, but we generally go to non-touristy places, or if we do, visit them early. That time of the year is usually the best weather-wise (although last year it pissed down the whole time!)

We go August or September every year for tailor season. Last year we went just before QLD school holidays and had the best weather and the best fishing we have had in a long time.

This year, however, we had quite a bit of wind and rain, and the fishing was ordinary. It’s funny how one week can be so different to the next. We always camp in zone 7, it’s close enough to Cathedral/Maheno if that’s where the fishing is and not too far from Waddy either, if that’s where they are.

I was always led to believe they gave the land of the former resort site to the indigenous (BAC). Do you know how accurate that is?

Julie, I have heard something similar. However, the title remains in the Crown as far as I know. They may have been given the resort lease when it still existed and did nothing with it. But if anyone knows, let us know.

Hi, great read, just a note that it’s Percy Wieden, not Wiedon. Percy is my grandfather, whom I never had the privilege of meeting.

Thanks, Kent. I just checked my book, and I spelled it Wiedon. The first error I will have to fix for the next reprint!

Very interesting. Thanks a lot.

I remember Orchid Beach well. Often flying over there with Telecom to repair and/or install communications cables. Sel Hewitt, if my memory serves me well, was the pilot who flew me over there to do the work.

I also have fond memories of the island, having spent time working over there as a forester in the 1980s.

Sel Hewitt also flew us over regularly and was a great old bloke.

I still remember one of his quotes, “there are old pilots, and there are bold pilots, but there are no old bold pilots.”

A great and interesting read for me. I stayed at the resort on occasions, using it as a base for QNPWS management matters.

Telecom workers also based themselves there during their ops, including throwing aerosol cans onto their rubbish fire, which started the major fire that blackened much of the northern end of the island down to the ‘A’ road, where it was contained by QNPWS, Forestry and Happy Valley brigade personnel.

My mum and dad (Stan and June Schulz) were volunteer gardeners at the Orchid Beach Resort when owned by Kieth Leach. We spent Christmas 1988 at the resort. They built a new pool after losing the first one to a cyclone. All the furniture in the resort was sold off. Some of it still remains in our family.

Good read. When Scarness Airport was established, Boat Harbour Drive was named Signboard Rd and stopped at Scarness.

The failed shark processing plant at Wathumba wasn’t the only freehold area, as mentioned. Only a couple of weeks ago (Dec 25), old RJ Bagnell passed away, who owned one half of the original Moonbi station at Moon point – after his father and McLiver had it, and only quietly relinquished to the state govt a few years back after having been a horse then cattle station since the 1800’s, and abandoned post WW2.

QNPWS tried to gate the Moon Pt Rd off after the 2011 floods, but were soon reminded of the legal easement that existed to the property. That family (GP Dickens) also held the Eurong lease, along with Aldridge’s, as a horse property from the 1880’s, and various forestry leases.

They are mentioned numerous times in Ike Owen’s oral history submission, who worked for them at various times on the island. They also donated the land on which the current Dundowran Hall stands and have a private family cemetery nearby. Hope this helps with your research on island/bay history.

Thanks, Cam. Some great information about the island’s history. I discuss the various leases in more detail in my book “Paradise Preserved”.

I thought the Nielsens donated the land for the Dundowran Hall? They farm the land and grow pineapples alongside the Dundowran Rd cnr with Lower Mountain Rd.

Hi Sue, at one stage, between the Bromileys and the Bagnells, they owned most of Dundowran. Their cemetery plot is on an easement out the back of Baldwin’s Farm, which is on the other side of Neilsen’s, so I’d guess they had the lot of it at some stage. I’ve read in a couple of places that Bagnell donated the land, but I’m happy to be corrected. I’m no expert.

Thanks and yes.

Thanks for documenting the island’s history. I had no idea there was a resort that once existed there, so it was really interesting to read all about it.

We spent many Christmas holidays there. My Grandparents were somewhat caretakers in the 80s, Roy and Val Jacklin. Christmas time was amazing, big trips to get there, but so much fun.

Your grandparents and my Mum and Dad were good friends😊. They loved Roy and Val !