What has happened in the last few days is the consequence of years of neglect of the bushfire threat in the national park, which in this area is tantamount to malpractice by fire agencies and the land manager.

– Denis O’Bryan on the Mallacoota fire.

On New Year’s Eve 2019, Mallacoota was engulfed in a strange, frightening darkness. As dawn was about to break, the sky blackened, and the town was covered in smoke and ash. Over 4,000 people gathered on the foreshore, waiting to be evacuated by sea. By the end of the day, 123 houses had been destroyed, but fortunately, no lives were lost.

The headlines at the time painted a picture of unstoppable catastrophe. Yet behind the dramatic images and government spin lies a different story — one of squandered opportunities, confused warnings, and a woefully inadequate firefighting response. The evidence shows that this was not an unavoidable disaster. It was a fire that could, and should, have been contained in the days before it reached Mallacoota.

A look at the fire

At 3:24 pm on Sunday, 29 December 2019, a fire was reported near Banana Track, in a remote part of Wingan State Forest close to Wingan River. It was caused by a lightning strike, roughly 26 kilometres east of Cann River and about 24 kilometres west of Mallacoota.

Weather conditions were mild. The Forest Fire Danger Index (FFDI) never exceeded 10. Officially, we are told that one firefighting unit responded to the blaze, although there are doubts about the accuracy of this information. The one unit may have been a fixed-wing aircraft doing surveillance. Reports indicated the fire covered 40 hectares, burning slowly westward under light south-easterly to easterly winds. It remained uncontained.

Even here, confusion clouded the situation. A Country Fire Authority (CFA) scale map indicated that the fire was closer to 400 hectares, suggesting it had been burning unnoticed for some time.

Local resident since 2007, Angie Cooper, said the fire was visible on the Digital Earth Australia Hotspots website the day before, 24 hours before it appeared on the VicEmergency website. She questioned why Emergency Management Victoria didn’t alert the public, especially since the weather forecast predicted it would eventually move towards Mallacoota.

Whatever the proper size, the conditions on the ground offered the best chance to control the fire. There’s no evidence that serious efforts were made to do so. The fire remained small during its first 24 hours after becoming public. Why wasn’t it attacked aggressively on the ground and extinguished? Why wasn’t a bulldozer used to track the fire while it was still small?

What is truly worrying is that dry lightning strikes in the area are common. In one summer in the 1980s, the Cann River fire brigade faced 350 lightning strikes. In the late 2000s, one storm generated 58 ignitions that had to be suppressed. Surely, the firefighting authorities are aware of this risk and prepared to respond promptly.

This is important because Mallacoota is at the end of a 23-kilometre spur road off the Princes Highway. It is surrounded on three sides by dense bushland from Croajingolong National Park, with the ocean on the fourth side. It is very exposed if a large fire comes close to the town.

To the locals’ best knowledge, because the fire response has been kept secret, no work was done to control the Wingan fire. One person at the Incident Control Centre stated that nothing was done because they were not aware of the fire until it had gained a significant headway. By then, with the heavy fuel loads, it was too dangerous to fight the fire on the ground, and the smoke was too thick for an air attack. I call that bullshit.

What is reprehensible is that no effective containment strategy was developed during relatively mild days once the elongated eastern flank became the new front after the southerly wind change.

Panic without fire

While the fire smouldered in the bush, residents and holidaymakers were bombarded with a stream of warnings and orders that bore little resemblance to the conditions on the ground. Around 48 fires broke out in East Gippsland after lightning storms on 21 November. While efforts to quickly contain and control 44 of these fires are commendable, the remaining four fires, located north and north-east of Bairnsdale, defied control efforts for five weeks, despite at least a month of favourable fire weather conditions. It was in this context that alerts and warnings were issued as fire weather conditions began to worsen on 29 December.

At 11:30 am on 29 December, an extraordinary text message was sent:

Everyone in East Gippsland must leave the area today due to the fire danger forecast for tomorrow. Do not travel to this area. It is not possible to provide support and aid to all the visitors currently in the East Gippsland region.

East Gippsland covers 21,000 square kilometres. It takes three hours to drive from one end to the other, passing through forests, farmland, towns, villages, and beaches. Evacuating “everyone” from such a large area was not only impossible but also needlessly alarmist.

Contradictions quickly emerged. A warning issued on the same day instructed residents to leave Wingan and Tamboon immediately, as the fire was “fast-moving and not under control.” This is despite the FFDI at Mallacoota being zero at both 9 am and 3 pm! The bad weather conditions didn’t eventuate that day. Another warning advised Mallacoota residents that it was “too late to leave” — even though the fire was still many kilometres away. These broad, premature messages spread fear but provided little clarity.

For Mallacoota residents and holiday visitors, it is a remote town situated in an area with some of the most extensive native forests in the country. So, where did many people go when they left? Some hooked up their caravans and headed for the safety of Eden and Merimbula further north, only to be moved on when fires reached those spots. They became bushfire refugees wherever they went.

The inconsistent messaging caused considerable confusion, worry and stress. It led to the premature activation of sprinkler systems, which left pumps without fuel when they were most needed. Many at the caravan park did not realise until it was too late that there was even a fire, let alone a meeting to attend. The park operator faced criticism for its inadequate notification.

In a surprising turn of events, after the initial warning, people felt relieved when three strike teams, comprising 19 fire trucks, arrived in Mallacoota on 30 December. They appreciated having so many resources sent to protect them and the town. Or so they thought.

It was only much later that they realised those extra crews were there by default. They were returning from deployment in the New South Wales fires and couldn’t proceed down the closed Princess Highway. They were seeking the same refuge that the town’s folk had to rely on. Despite these extra resources, over 120 properties still couldn’t be saved.

The missed opportunity

With severe weather forecast for 31 December, the crucial task on 30 December should have been to contain the eastern flank of the fire before it could threaten Mallacoota. This may have involved securing containment lines along the Wingan River, Betka River, or Mallacoota Road, and conducting back burns under mild conditions, particularly as it turned out to be a milder day.

Instead, the record shows inaction. By the evening of 30 December, the fire had spread to 22,000 hectares. The sky glowed orange, then deep red. Conditions remained moderate, with the FFDI around 30, and steady but not strong winds mainly from the northeast. It was, in fact, the last real chance to stop the fire before the forecast change. Yet the firefighting effort stayed minimal and unclear.

The public has never been informed about the tactics that were employed or not employed. What we do know is concerning. The fire escalated rapidly under relatively mild conditions. We are not even sure if any firefighting vehicles were dispatched to confront a fire front that would soon extend 15 kilometres. The Mallacoota brigade members were tasked with patrolling and protecting people who took “shelter” at the Main Wharf and along Karbeethong foreshore. They didn’t play an active role in fighting the fire.

The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning’s (DELWP) operational “Fireweb” website included an instruction stating that no new fires were to be started in the landscape, effectively prohibiting backburning. Gus McKinnon’s bulldozer, stationed at Cann Quarries, was on standby but was never used.

A trusted local source was told, after questioning a Parks Victoria staff member about the fire, not to worry, as it was never going to reach Mallacoota.

The fire spread

At 6 am on New Year’s Eve, the wind shifted to the south-west. By mid-morning, gusts of 35–45 km/h pushed the eastern flank towards Mallacoota. In four hours, the fire travelled 30 kilometres — a typical rate of spread for coastal heath, but devastating in its size.

By then, the only escape route had been cut off. Thousands of residents and holidaymakers were stranded, gathering on the foreshore. Sirens wailed, ash fell from the sky, and day turned to night. As one resident later recounted:

There’s no fuel, there’s no water. You turn a tap, and nothing comes out. And the electricity’s gone.

A mass evacuation took place, first by the Navy ship HMAS Choules on 2 January, followed by air and sea efforts in the days that followed. It was the largest maritime evacuation of civilians in Australian history. The bravery of local CFA brigades, police, and defence personnel at the shoreline is undeniably admirable. But by then, the damage was already done.

For weeks, Mallacoota remained cut off. Roads were damaged, power was out, and supplies were dwindling. Residents saw a landscape stripped bare. One woman recalled:

You come here to live amongst all that nature, and suddenly it’s not even a leaf.

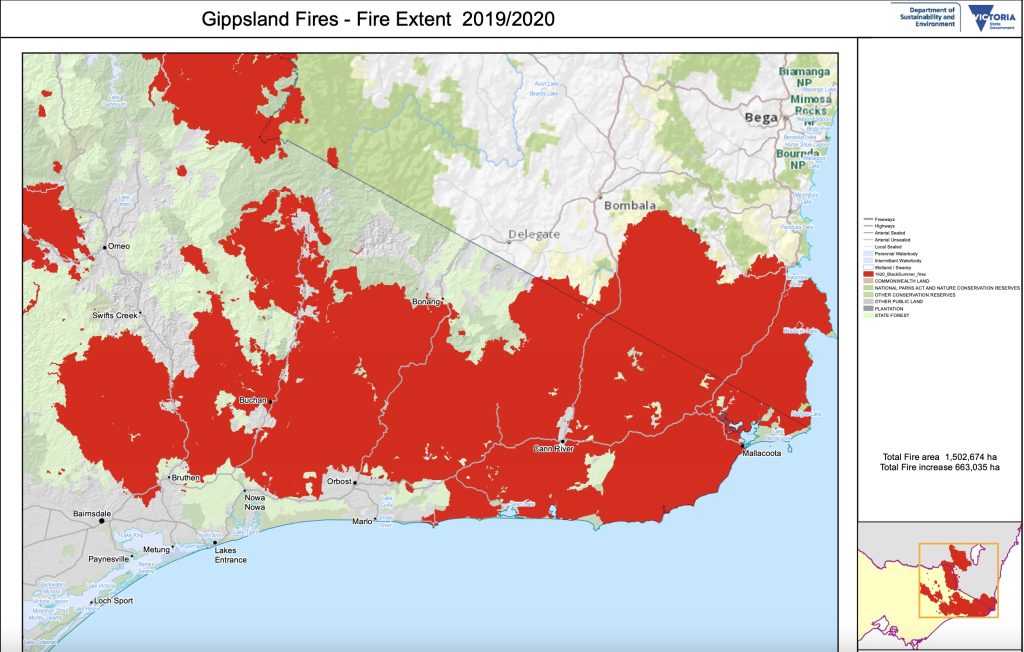

By late January, 1.5 million hectares had burnt across Victoria’s east and north-east. Although heavy rain provided relief, it also introduced new threats, including flooding, landslides, and unstable, fire-damaged forests.

The media narrative: spectacle over scrutiny

On 31 December 2019, mainstream coverage primarily focused on apocalyptic imagery, mass evacuations, and heroism. That focus was understandable at the time. However, it also overshadowed uncomfortable questions about preparedness, fuel loads, initial attacks, and why milder periods weren’t utilised more aggressively to combat the fire when it was small.

Major outlets led with catastrophe and evacuation, not governance and prevention:

- ABC News: “‘Looks like a warzone’ … Mallacoota … woke to blackened skies.” ABC

- ABC News (day-of eyewitness): “sky turning from pitch black to blazing red.” ABC

- 9News: “After red hell, Mallacoota awakens to a scene of devastation.” 9News

- 9News (logistics emphasis): “First rescue ship arrives in Hastings carrying fire evacuees.” 9News

- The Guardian (live blog banner): “Tens of thousands flee in mass bushfire evacuation.” The Guardian

- BBC (via archive): “Navy rescues stranded from ravaged Mallacoota.” Infodecay

- Sky News (UK): “Navy begins evacuating thousands trapped in coastal town.” Sky News

Each of these headlines is accurate on its own. However, taken together, they reinforce a narrative of unavoidable disaster and effective emergency response, while sidelining deeper issues, such as inadequate planning, poor resourcing, and ineffective fuel management.

What this framing did and didn’t cover

Stories repeatedly highlighted the red and black sky and beach refuge scenes — “woke to blackened skies,” “pitch black to blazing red” — which powerfully conveyed fear but did little to examine why the fire was able to run so far and so fast through heavy fuels next to a town at the end of a single road when weather conditions were conducive to an aggressive attack.

Much coverage measures effectiveness by the scale and speed of evacuation — “first rescue ship arrives,” “Navy rescues stranded,” “mass bushfire evacuation” — implicitly shifting the benchmark from prevention and containment to extraction and relief.

Live blogs and rolling updates amplified widespread alerts and a declared state of disaster, often without sufficient consideration of whether warnings aligned with local FFDI or if earlier, milder windows for direct attack or flanking containment had been overlooked.

Follow-ups did occur (community trauma, recovery, climate context), but even retrospective features tended to re-emphasise evacuation heroics (“trapping … people without power or water”) rather than examining fuel management gaps or early tactics around the Wingan ignition.

How this experience shaped public memory

The dominant themes of red skies, beach refuge and Navy rescue became the story. As the fire swept through the town, Australian Navy vessels started rescuing evacuees from the Mallacoota foreshore in what local MP Darren Chester called an “unprecedented mass relocation of civilians”. Images of that desperate evacuation spread worldwide. ABC packages, 9News dispatches and international wires followed in a cinematic sequence that felt inevitable, overshadowing the period before the southerly change when the eastern flank might have been contained and sidelining scrutiny of long-flagged fuel hazards around Mallacoota.

But what the public and news media conveniently ignored was that firefighting authorities did so little to combat the fire when they could, and nothing was done when the threat to Mallacoota became clear, except call a meeting of community and holidaymakers on 30 December at the oval about 10:30 to warn them about the approaching fire.

Over 4,000 visitors on holiday thought it was safe to stay, even though by then they had no choice. The meeting instructed them to leave within the next few hours, despite being informed the day before that the road out was already closed! They were left to fend for themselves as outside help couldn’t reach the town.

What was missing or under-reported, and the role of fuel management

Fuel profiles and treatment history near the ignition and town interface were overlooked in favour of focusing on evacuation imagery saturation. There was limited detail on numbers, tasking, or containment efforts on 29–30 Dec when the FFDI and winds still permitted more proactive work on the critical and exposed eastern flank of the fire.

Few outlets questioned whether region-wide alerts (“leave all East Gippsland”) may have increased anxiety while reducing actionable detail. Most importantly, the media rarely compared emergency response investment with the much smaller, piecemeal planned burning footprint in East Gippsland leading into the 2019–20 fire season.

Despite claims by some academics to the contrary, we know that broad-scale fuel management outside the fire season is vital for giving firefighters more options in tackling fires, like the Wingan River fire. Experienced fire researchers John Cameron and David Packham analysed 12 major Australian bushfires that affected urban areas from 1967 to 2019-20. Their study showed that human deaths were linked to fire intensity, not FFDI. Both fire intensity and FFDI account for weather, but only fire intensity considers the forest fuel load. Forest fuel levels can be managed, but the weather cannot.

For example, lessons from the March 1983 Cann River fires highlight the importance of fuel management for protecting Mallacoota. These fires were part of the Ash Wednesday major fires, which followed a prolonged drought, similar to the dry conditions experienced in 2019-20. It was reported that connecting areas recently fuel-reduced, along with aggressive initial attack and back burning to establish containment lines, were vital and effective control strategies in such dry conditions. Earlier fuel reduction burning to the west of Mallacoota in 1979-80 had a significant benefit in protecting the town.

Another analysis of town and city bushfire protection case studies by experienced forester John O’Donnell reveals that adaptive fuel management and mitigation have helped limit the impacts of bushfires on communities across Australia and the USA.

Other recent evidence about the efficacy of fuel management comes from an experiment set up to assess the effectiveness of prescribed burning and mechanical thinning in a forest near Mallacoota. The experiment included four treatments, each replicated in three blocks: thinning with residues left, thinning with residues burned, prescribed burn, and an untreated control.

The burning and thinning treatments were carried out from 2016 to 2018 and were impacted by the 2019-20 wildfires. As there were no suppression efforts near the study site, the resulting burn pattern and severity were determined by the interaction between landscape fuels, weather and the fire.

A post-fire analysis revealed that sites that were only thinned and those that were untreated experienced the most intense burns. In contrast, the prescribed burn areas (both high- and low-intensity) did not ignite from the approaching wildfire. This clearly supports the conclusion that the benefits in reducing fire hazard last for at least three years after fuel modification treatments in these eucalypt forests.

Following the 2019 fire, Victoria’s veteran fire scientist, Kevin Tolhurst told a gathering during a tour of the high country organised by The Howitt Society, that legislation limiting fire was a tragedy:

We can’t ever remove fire from the landscape, it’s a natural part of the environment just as much as sunlight, wind and rain, and that’s what is not well understood because the politicians keep telling us that ‘we can protect you, put your trust in us’ and the government agencies want to be in control. So, what is happening in this idea that we can control these things has been proven to be a falsehood.

We’re trying to control fires, but there’s a limit to what we can control, so the only fires that end up burning the landscape, the megafires, they’re the ones beyond our control, they’re the most damaging – both to the environment and all the human life and property

We really need to change our whole philosophy of having fire in the landscape.

Yet, despite the overwhelming evidence, CFA chief officer Steve Warrington, in the aftermath of this tragedy, believed calls for more fuel management burning were not a silver bullet:

Some of the hysteria that this will be the solution to all our problems is really just quite an emotional load of rubbish, to be honest.

In contrast, former Department of Sustainability and Environment chief fire officer with 40 years of firefighting experience, forester, and East Gippsland local Ewan Waller called for clear direction and policies, focused mainly on prevention rather than response:

How will the backcountry be handled? No one is answering that. It needs a sensible but large burning program. It has to happen fairly soon — the regrowth is happening now. Within three-to- five years there will be a massive fire scape that we have to manage, or we will be back to where we were. People have got the answer, but have we the fortitude to do it?

Waller is also highly critical of the undue influence of academics and green activists in fire management policy, arguing they ignore evidence-based answers from scientific work and cherry-pick arguments that only serve to confuse governments about which policies to adopt.

What evidence was there of being prepared?

In the months leading up to the 2019–20 bushfire season, Victorian fire agencies and government spokespeople kept repeating the familiar mantra:

We have never been better prepared.

The reality on the ground at Mallacoota proved otherwise. Mallacoota avoided disaster in 1983, which bred complacency. For years, both authorities and locals turned a blind eye to the growing fuel hazards surrounding them. It was a town encircled by plenty of fuel.

In December 2019, the bush around Mallacoota was bone-dry after three years of drought.

Residents knew it. Larry Gray, a long-time local, summed up the concern:

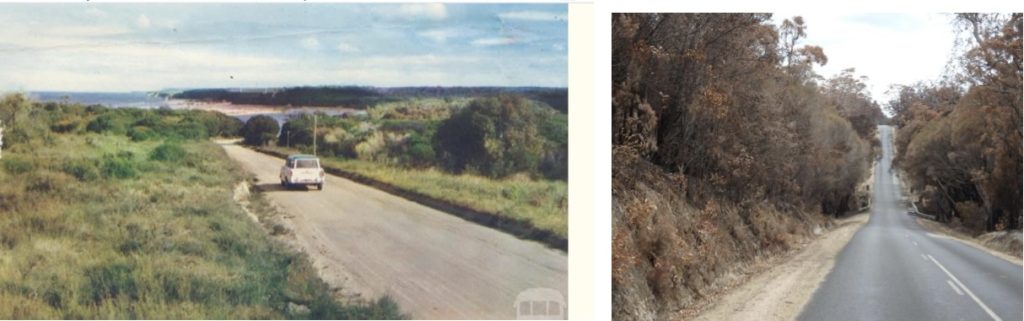

When I was a kid, you could ride a dirt bike down trails all through the bush. Now they’re overrun with trees and scrub. It’s just thick with fuel.

He wasn’t exaggerating. Records show that the last major prescribed burn near Mallacoota was in 2014, and another occurred further west in 2010. Since then, there have only been a couple of small burns on private land. The most recent severe wildfire happened in a relatively small area in 2009. That left a decade of uninterrupted fuel growth.

By 2019, the surrounding forests had built up surface fuel levels of 20–25 tonnes per hectare — equivalent to almost 9,000 litres of petrol per hectare.

The results were predictable. When the fire finally arrived, it created pyrocumulonimbus storms — a phenomenon where fire plumes are so intense they generate their own thunderclouds. This only happens when fuel loads are allowed to build to disastrous levels.

For decades, Victoria managed fire risk using quantitative targets, which were a specific number of hectares to be burned each year. After the Black Saturday Royal Commission in 2009-10, a five per cent annual prescribed burn target was introduced. However, this was soon replaced by the “residual risk” model, which claims to measure the percentage reduction in statewide bushfire risk based on the burns that have been completed.

On paper, Forest Fire Management Victoria (FFM) claimed that the “residual risk” had remained below 70 per cent for three consecutive years. In reality, it meant very little in terms of burning where it mattered.

In Mallacoota, the only action taken was some mulching earlier that year, which was introduced on a “large scale” behind the town’s water reservoir on the western edge of Mallacoota as an alternative to fuel reduction burning. Supporters claimed it was a great success. However, it was the wind-driven burning piles of mulched material that directly contributed to the increase in flying embers when the Wingan fire struck Mallacoota.

The figures are stark. In the four years before Black Summer, only 0.6 per cent of the forest in eastern Victoria was fuel-reduced each year. Eighty-one per cent of those treated patches were so small that even moderate spotting could easily ignite them. Around Mallacoota, prescribed burns were nearly non-existent, meaning a fire could run for 10–50 km before hitting anything recently treated.

“Residual risk” gave the appearance of action but silently lowered accountability standards. It was a statistical distraction hiding a harsh truth that the bush around Mallacoota had not been adequately prepared for a significant fire in years.

In the official inquiry into the fire, the Inspector-General for Emergency Management (IGEM) praised “briefings, training and exercises” as evidence of preparedness. However, he did not address the main hazard of fuel build-up. Instead, he offered excuses such as unfavourable weather preventing burns, models having limitations, and community concerns about fuel loads reflecting “fundamental differences in values.”

This bureaucratic doublespeak is insulting. Locals weren’t just talking about abstract “values”; they were pointing at the bush around their homes and saying, “This will burn.” And it did.

Many understood the threat was real. They wrote letters and made representations to Parks Victoria, DELWP, FFM, local councils, and local politicians. A group called the East Gippsland Wildfire Taskforce was formed, which later evolved into The Howitt Society. However, its efforts to advocate for increased fuel reduction work were to no avail.

For example, a block behind Karbeethong, where 11 houses were lost, is bordered by Karbeethong Road, Genoa-Mallacoota Road and Mullet Creek. It last burned 19 years ago and had been planned for a prescribed burn for ten years before the fire. It was prepared for a burn from 2016-17, advertised for a burn in 2017-18, but was finally cancelled in 2019 due to objections raised by some residents over the presence of a flying fox colony in nearby Mullet Creek. Ironically, the strongest objections to the fuel reduction burn came from residents who lost their houses along Karbeethong Avenue.

The East Gippsland Shire Council was also quite complacent, for instance, refusing a private landowner’s request to clear hazardous tea tree and black wattle scrub just a couple of weeks before the fire because a vegetation overlay protected it. Ironically, it was bulldozed by DELWP a day after the fire in preparation for further potential impact!

Local MPs, in opposition, recognise and acknowledge the problem but, unfortunately, have been ineffective in convincing the government to take action to protect people and assets. Sadly, the IGEM inquiry mainly focused on response and recovery, ignoring the deep-rooted deficiencies within governments and their bureaucracies regarding preparedness and mitigation. A more independent coronial inquiry could have uncovered these significant failings, but unfortunately, the coroner chose not to hold one.

Preparedness is not a press release. Nor is it a “residual risk” model. It involves the tough, unglamorous tasks of keeping fuel levels low, maintaining access tracks, training crews, and positioning resources where they are most needed. On all these fronts, Mallacoota was overlooked and woefully underprepared, and still is.

Operational failures and culture of spin

Even once the fire started, the idea of preparedness was shown to be a myth. Cameron heard concerns from CFA volunteers who reported delays in deployment and tasking. Crews waited around for hours. There were no incident plans, so incoming crews began their shifts without maps or clear objectives. Briefings and handovers were often inadequate, and information was either incomplete or arrived late. Resourcing was consistently low. At Mallacoota, six firefighting vehicles faced a 15 km fire front.

These are not the signs of a system “better prepared than ever.” They reflect what appears to be a dysfunctional bureaucracy more concerned with optics than results. It is alarming and concerning that in 2019-20, after the state had faced a series of fire disasters in 2003, 2006-07, 2009, and 2012-13, these issues still persist in Victoria.

What is more alarming is that in September 2017, more than half of the volunteers in Mallacoota’s fire brigade resigned due to wrongful accusations of misappropriating funds at a successful community engagement and education event. A reliable local source also informed me that the district headquarters had launched a campaign to cull “dead wood” from the brigade, making it easier to achieve a quorum at brigade meetings. Immediately after the mass resignations, the CFA erected banners advertising for recruits.

Since then, the CFA has participated in a few small DELWP burns around town, aiming to provide brigade members with fire experience and support for understaffed crews, thereby helping the burns to proceed. However, they were hardly effective in protecting the town when a large fire broke out.

Mulching became a convenient substitute for the CFA, as many of the newer Mallacoota fire brigade members had limited experience with fuel reduction burns – an alarming reality considering the town is entirely surrounded by forests carrying high fuel loads.

The neighbouring Cann Valley brigade nearly fell apart. Local sources reported internal conflict within the brigade, including disciplinary disputes that had a profound impact on morale. Tragically, one member later took their own life. During the 2019 fires, Cann River had just two active members.

The most damning aspect of all is the culture that led to these failures. Government agencies have become skilled at media management through warning campaigns, red-alert texts, and fear-driven messages to show their vigilance. However, while they put effort into communication after the fire started, they invested much less in hazard reduction or operational planning outside the fire season when conditions are favourable.

Locals claim that some Parks Victoria staff expressed concern that visitors dislike seeing a blackened landscape after burns. Unfortunately, they are easily influenced by opposition from some residents — voiced on social media and local outlets — which contributed to the cancellation of the first planned burn since the 2019 fires. When I drove into Mallacoota last January, I was horrified by the lack of any fuel reduction works since the fire.

A preventable disaster that left a town exposed

When the fire hit Mallacoota, the outcome was not surprising. It was the expected result of years of policy drift, complacent management, and ignoring the obvious. Residents had pleaded for burns. Long-time residents can’t recall any fuel reduction burns on the southeast side of town, certainly none in the last 20-30 years. They warned of a thickening coast of tea tree so close to the town. Instead, they received assurances that the system was “ready.”

Before the dedication of Croajingalong National Park in 1977, the tea-tree was almost non-existent due to regular burning and grazing as far as Shipwreck Creek. According to Cooper, in a bizarre twist, new green residents complain about the removal of tea tree as if it were a rare native plant that needs protection.

The government wants you to believe that the Mallacoota fire is a story of nature unleashed. Instead, it is a case study in how the abandonment of practical, measurable fire management left a community disastrously exposed.

The record tells the story:

- For two days, weather conditions were mild, and the fire was small.

- Little effort appears to have been made to secure containment lines or attack the fire.

- When the weather change came, the firefighting response was utterly inadequate.

- Warnings were excessive, contradictory, and poorly targeted, creating unnecessary panic and reflecting panic within the control centres.

Ultimately, Mallacoota was left to burn due not only to natural forces but also to human failings. Denis O’Bryan’s words at the top of the blog strike a chord – years of neglect, poor land management, and panicked firefighting efforts turned a controlled fire into a national spectacle of fear and loss.

Just a decade after the Royal Commission into the devastating 2009 fires, it’s upsetting to see how poorly Victoria was prepared for another major bushfire, despite the rhetoric from government agencies and the government.

The Mallacoota fire wasn’t an unprecedented event; the 1983 fires show that. As a submission from a Mallacoota resident to the 2019-20 Royal Commission stated:

Unprecedented is a word used by Governments or Authorities to defend against their lack of willingness to accept responsibility for proactive behaviour with planning, preparedness and action.

Mallacoota was far more than a victim of the 2019-20 bushfires. It served as a stark example of folly – a careless display of poor fire management that must end, and those responsible must be held accountable.

Well done again Robert!

Sadly, this tale could be repeated across the country during every major drought. Lack of management due to academic and political ideology, allowing fuel loads to build unchecked and fire trails to fall into inaccessibility. Then centralised, back-footed, risk averse fire fighting control shying away from any tough decisions.

Mallacoota was but the most dramatic of the many avoidable disasters that occurred that summer and many times before during recent droughts.

Well done Robert.

It is worth noting that there are other Victorian fires that have been able to grow from controllable small fires to uncontrollable conflagrations due to failures to take advantage of lengthy periods of benign weather immediately after they were detected. The Deddick-Goongerah fires in 2014, the Wye River fire of 2015, and the Snowy River NP fire of 2019-20 spring to mind. The latter fire grew to threaten the towns of Orbost and Cann River at around the same time as the Mallacoota fire.

Undoubtedly, lack of fire-fighting resources was a factor in the Mallacoota fire, given the other fires simultaneously occurring in East Gippsland, and further exacerbated by the politically-forced downsizing (and since the ultimate closure) of the timber industry which was previously a major source of fire-fighting equipment and expertise.

I am familiar with the coastal forests west of Mallacoota having been formerly posted to Cann River Forest District, and having spent 6 weeks working on the 1983 fire which also started north of Wingan Inlet and spread to Mallacoota. The fuels are hard to cool burn in a controlled manner due to their thickness and flammability, with dense and impenetrable wire grass prevalent throughout. It is also such a large area, that it needs a huge commitment to prescribed burning, which the Victorian parks bureaucracy is now ill-resourced (and ideologically lukewarm) to undertake.

Just a small point. Ewan Waller was formerly the Chief Fire Officer of the Department of Sustainability and Environment, not the CFA. Also, Mallacoota has water on about a third of its perimeter with the ocean to the south and south east and the extensive wide estuary of the Mallacoota Inlet to the east and north east.

I am familiar with the Croajingalong.

I have a similar analysis of the Wye River fire for next month. Thanks for the correction on Ewan Waller.

Yes! 2018/19 was a meeting of many issues that could have lessened the impact of a terrible drought and a huge fuel load. Your comprehensive investigation does talk about the nationwide issue of the need to carry out controlled burns when the opportunity is there. Sadly, the many agencies involved struggle to be able to do what they know needs to be done in total frustration. Another factor is that the total bureaucracy and impenetrable layers to get things done means that brigades lack the opportunity to carry out the meaningful work that they know needs to be done. And as a result people lose interest and leave.

And we stand in our brigade headquarters as I did last weekend looking at the bush that surrounds us in the most vulnerable brigade in Sydney and we can’t do a thing. To do a burn requires negotiation with Aboriginal Lands Council , Council, NPWS and the RFS. To date there has been one in memory and a stuff up it was because in the end it happened after rain and was an abject failure because we couldn’t get it to burn! But it had to go ahead after all the effort that had happened to get permissions.

In terms of fighting fires, with respect, bushfires can only be guided with good management and favourable conditions, to avoid harming people as the first priority and property where possible. If luck prevails with wind and weather the very best outcome is to be able to burn them back on themselves. In the fuel load conditions that existed and the panic nationwide, what happened in 2018/2019 was exceptionally bad. It was a multilayered disaster. The people on the ground did the best they could with the resources they had.

The failures come from the top, from the governing bodies that do not work together.

Please remember your emergency service personnel put their lives on the line to help where they can and many are volunteers.

As long as inexperienced personnel can achieve nebulous qualification as “Incident Controllers” and “career” staff are promoted into critical operational management positions the continuing mismanagement of fire incidents will continue and escalate. Unfortunately, the emasculation of land management agencies and the loss of personnel with the skills to light fire and fight fire has contributed to this sad state of affairs. The centralised control is necessary for the effective and efficient marshalling of resources; however, the front-line decisions should be left to the on-ground controllers.

As always, I urge people to revisit the Stretton Report and consider the details and the recommendations therein and critically review the current situation and every event since 1939…

Hi Robert. Good overview. If you email me I will give you a copy of my report that as I recall I provided to the inquiry. It supports your work but contains a bit more detail.

This blog highlights a problem we are facing with managing our “natural” environment. Our environmental movement has gained such influence in the community at large, that they now have an overbearing influence. If you try to do something like hazard reduction there is every chance you will be criticized for what you did or how you did it. Much easier to wear criticism for doing nothing than to be accused of doing something that a well-practiced critic chooses to attack.

If you do nothing and the worst eventuates it can usually be blamed on the circumstances at the time.

Having experience of NSW north coast and tablelands it has always amazed me how here in Victoria the dense undergrowth comes right to the edge of major roads. Hence, major roads are vulnerable to early closure due to wildfire. Hazard reduction not only reduces the immediate threat of fire but also ensures that trees threatening to fall and close vital communication roads have already been removed.

On the north coast fires were often believed to have been lit by a “scoah” ( some chap on a horse). Down here in Victoria the most convenient culprit is “dry lightning”.

The 2019 – 2020 fire season is a classic example of Harry Lukes “March of the Fire Season”.

To escape the Canberra cold in August, I booked a week in Port Douglas. On 20 August, en-route Canberra to Brisbane, QF 1546, I observed a fire in the forest between Grafton and Glen Innis and thought, “that’s a reasonable sized control burn”; there were roads around it that I surmised would be boundaries, but no sign of burning out from aloft.

A week later, we flew back (27 August) and the fire was still burning but had expanded to around 3 times the size again with little evidence of control. A couple more smokes were visible to the south. Fire outbreaks continued over the following months in the NSW forests, marching south with the fire season and burning large areas which, apart from a couple of severe days, were under relatively mild weather conditions.

In late November, I drove around Gippsland with Vic Juskis. On 27 November, we observed the smoke of 3 fires, presumably the result of lightning the day before, in the forest between Buchan South and Bruthen. There was no sign of suppression activity.

I was familiar with the area because it was the site of my research, Project Aquarius, where I evaluated the limits to suppression by handtools, bulldozers and water-bombing aircraft in 1984-5. I said to Vic, “These fires should be suppressed overnight”.

We drove past 5 days later, after mild weather and a little rain. The southern perimeter had reached the highway between Bruthen and Nowa Nowa, burning quietly, but still no evidence of suppression activities.

It appears as though these, and other fires, were allowed to burn for more than a month before extreme weather on the 31st December.