Another Spring Carnival in Melbourne has come and gone. I wasn’t born a racing man. While I went to school with guys steeped in the Sydney scene at Royal Randwick Racecourse, I was never hooked. I have a couple of mates in Hervey Bay, Dave from “the Shire” in Sydney and Macca from Alice Springs. They regard Saturday afternoons as sacred. Each Saturday, they assemble in their fortress at home, newspapers spread out, form guides open, tips debated, and gambling pools assembled. They had or have part-shares in horses, ran gambling groups, and both live for the theatre of it.

Dave’s kids grew up knowing Saturday afternoon was race day. Even his eldest daughter had to reschedule her wedding from the long weekend in June, affectionately known to racing purists as Stradbroke Day. As the eldest daughter, her true love for her father shone through.

I listen, amused and bemused. On one level, I understand the colour, the sound, the spectacle. On another level, it simply isn’t me. My own hard-earned pay went to groceries, bills and the next writing project, not to a punt on a filly’s maiden or a mate-of-a-mate’s “best tip”.

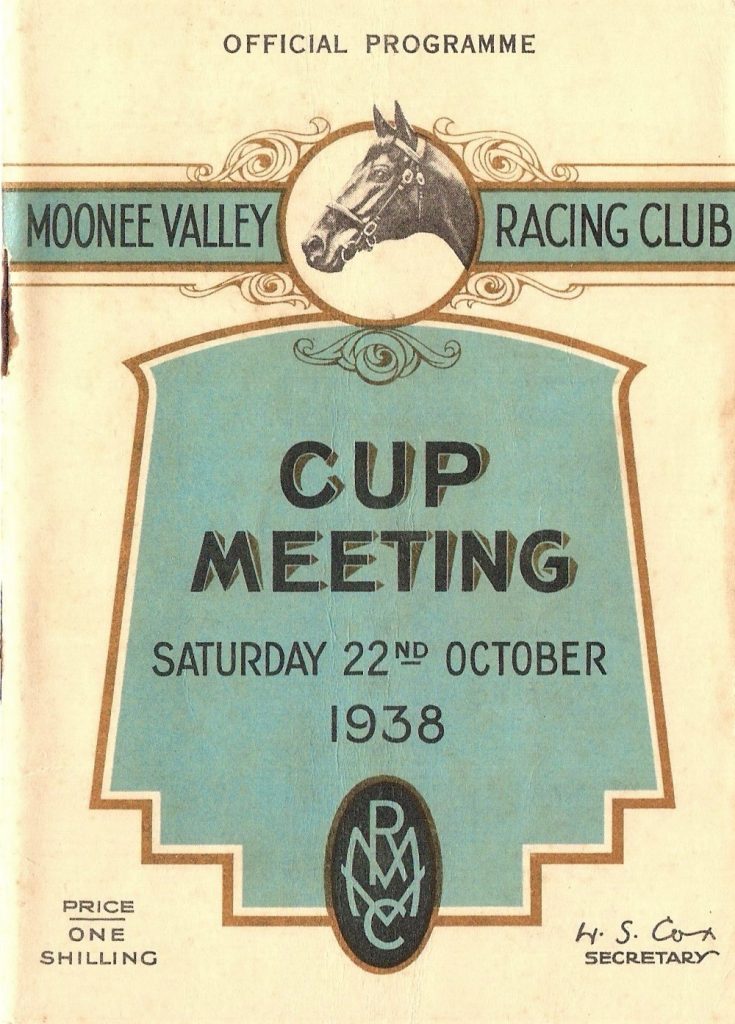

Yet their nostalgic rants — the “you should have been there” moments, the stories of brilliant come-from-behind wins, the heartbreaks of near misses — started to pique my interest. And as I researched an earlier piece on the remote Landor Races in 2021, when staying in Geraldton, Western Australia, I realised that what mattered wasn’t the bet but the story. The place, the memory and the ritual. This year saw the last running of the Cox Plate on the original Moonee Valley racetrack. The Valley’s looming transformation seemed especially poignant. It is not just a racetrack being updated, but the possible loss of a particular kind of racing soul.

The theatre of the Valley

There’s no venue quite like Moonee Valley. It is compact, intimate and electric. The track winds in a tight saucer, almost like a velodrome for thoroughbreds, with the grandstand so close you feel you’re part of the action rather than observing it.

The layout is distinctive. It has a short home straight, a highly cambered turn into that straight, and jockeys scramble for position before the real duel begins. The 400-metre marker — the so-called “school” — has traditionally been where the brave make their move, where legends are born. This track shape demands something different from horses, jockeys and trainers. It isn’t just speed, but nerve, timing, the ability to launch at just the right moment and overtake before the bend tightens, the short straight ends, and you’re on the line. It is high drama.

And the atmosphere holds you. The crowd is tightly packed around the rails and the air vibrates with anticipation. The Valley hosts one of the country’s iconic races – the weight-for-age Cox Plate in spring each year. It’s the last race on the card. One writer described it as:

The championship … your life changes if you win a Cox Plate, you are a champion forever.

The two minutes it takes to run the Cox Plate at Moonee Valley turns some thoroughbred stars into legends. Punters aren’t just watching their horse win. They feel the crescendo, the surge off the bend and the roar of the crowd as the horses reach for the line. It’s theatre at its purest.

Champions often use the Cox Plate as a lead-in to the Melbourne Cup (though the reverse is rare). Weight-for-age means no extra kilos to compensate, the field is always strong and the pressure is immense.

The ritual of the day, the crowd, the known benchmarks all combine to form the myth. Trainers will say: get position at the 400m, commit or vanish. Jockeys will say: stay in touch into the turn, keep momentum, don’t get hemmed in. The track’s geometry favours horses with tactical speed, courage, and a turn of foot.

Unlike more sprawling venues such as Flemington, with its long, sweeping straight, or Randwick, with its majestic setting, the Valley is compact, with the crowd, the horses and the track all close. The short straight means a leader emerging early has a chance. The camber and turn mean that those who are sucked back and wide often struggle. Tactics matter immensely. A miscalculation around the turn at Moonee Valley can cost a champion. The Valley rewards precision and punishes hesitation.

Sunline’s failed bid for a third consecutive Cox Plate in 2001 is a perfect example. The mighty Kiwi mare had led for most of the race, but as she rolled a touch wide at the home turn, Northerly pounced, slipping through on her inside to steal victory.

Makybe Diva, the three-time Melbourne Cup queen, also found The Valley’s bends too sharp for her long, rolling stride. It is a course where her famous finishing burst could never quite unwind in time. This is what makes the track both maddening and magnificent. A champion can be undone not by lack of courage, but by a moment’s misjudgement on that unforgiving camber.

The Cox Plate: the race of champions

First run in 1922, the Cox Plate — the Group 1, 2040-metre contest — has come to be regarded as Australia’s premier weight-for-age middle-distance race. Because it is not handicapped, the very best horses tend to feature. The sort that are capable of bedding down in history, not just a number on the tote board.

The list of winners reads like a who’s-who: Phar Lap and Tulloch and Saintly; the three-time winner Kingston Town (in 1980-82); Might and Power roaring home in record style; and, of course, Winx’s four consecutive wins (2015-18) in one of the most dominant weight-for-age performances in history.

Winx was almost equine perfection, and The Valley amphitheatre was her own stage.

But no Cox Plate has embedded itself in racing folklore quite as much as that of Bonecrusher and Our Waverley Star in 1986. As the two Kiwis peeled away from the pack, jockeys Lance O’Sullivan and Gary Stewart went stride for stride down to the wire, a spectacle that will forever be immortalised in racing history. The crowd roared as they locked horns, the tension mounting with every bound. And in that tight, heart-stopping finish, race caller Bill Collins gave us one of the sport’s most unforgettable lines:

Bonecrusher races into equine immortality!

It was the perfect summation of a moment that captured not just a result, but the spirit of The Valley itself.

A few years earlier, another champion had already written his name into Cox Plate folklore. Kingston Town completed the first Cox Plate trilogy in 1982. In doing so, he also prompted a rare mistake from “the Accurate One” himself. The champion galloper was niggled at the 450-metre mark, prompting Collins to declare:

Kingston Town can’t win!

But the slip-up made the moment even better. The champion picked himself off the canvas halfway down the straight. He stormed home, forcing a humble correction and one of racing’s most memorable redemptions:

He might win yet, the champ… Kingston Town is swamping them!

But amid those immortal victories lie stories that break the heart. None more so than Dulcify’s record seven-length romp in 1979. Set alight by Brent Thomson near the school, Collins famously called:

Dulcify has won by a minute, and that’s the way he might win the Melbourne Cup.

Yet fate had other plans. Ten days later, in that very Cup, Dulcify fractured his pelvis and had to be put down. Forty-six years on, the memory still jars the traditionalists. It serves as a reminder that the pursuit of greatness and glory can run in the same stride as tragedy.

The redevelopment and the end of an era

And now comes the sad turn. The Valley, as we know it, is about to change. A 21-month, approximately $220 million redevelopment project will relocate the grandstand to the northern boundary, freeing up the land for residential, retail, and commercial development. That is, big money from big land deals. The track itself will be widened, the straight lengthened and more runners accommodated. The iconic “school” at the 400m mark will become the winning post. For a track whose identity has rested on the tight turn, the short straight and the surge from that school, this is seismic.

What will remain of the theatre? The camber will be retained, they say. The proximity of the stands will be improved, they say. Yet the layout will change. The straight will run longer. The geometry will shift. The tactics will change. The old markers — the 400m school, the bend into a short straight — will no longer be. Future winners won’t have that same marker. They will invade a new space.

The Valley’s uniqueness lies not just in its layout but in its memory-scape. The spatial intimacy, the whip cracks, the fleeting moment between bend and straight. Those things may survive, but they will do so in a different way. Will the roar be the same when the straight is longer? Will jockeys ride the bend the same way if there’s room to change tactically? Will the crowd feel the same wall of noise if the course opens out more?

When racetracks undergo facelifts, the track itself often remains intact: think Flemington and Randwick. But The Valley is different. Here, the track is being redesigned. A change to the layout is a change to the very DNA of Moonee Valley. Sadly, it will be a change to where champions are born.

I, who have never been a committed punter like Dave and Macca, feel a pang of loss. I’ve grown to appreciate the cultural artefact that is the ritual of the Saturday card, the majesty of these weight-for-age champions, the way the crowd leans into the rail as the field turns. And now we risk losing the nuance.

Victoria vs New South Wales: the race for racing’s soul

But this story is not just about one track or one race. It’s about the broader shift in Australian spring racing. Victoria has long dominated the Spring Racing Carnival with its Melbourne Cup, Caulfield Cup and Cox Plate. They sit in the collective psyche. New South Wales, meanwhile, has made its move. The Everest is just nine years old, offering a $20 million purse, drawing a 50,000-strong crowd at Randwick, and smashing betting turnover records. It is flashy. It is big. It is commercially aggressive. But does it carry the same heart? The same soul? The same history?

Melbourne’s advantage has always been more than the money. It has been the layers of meaning. The many decades of great horses, the drama, the rituals, the pundits, the callers, the stands that echo with stories, and the markers that matter. Yet, this year, Channel 7 commentator Bruce McAvaney was at Randwick for The Everest rather than the Caulfield Cup. A moment that felt emblematic as the commercial race overshadowed the traditional one (yes, I’m aware there are other dynamics at play, but symbolism matters).

There is a tension between spectacle and soul. The Everest is a spectacle. The Cox Plate has soul. Sydney may riches-rattle and build big prize-money races, but the question is, can you buy nostalgia? Can you manufacture the uneasy hush of a packed grandstand as the field rounds the turn at Moonee Valley, the crowd holding its breath before the surge? Perhaps not. If the Valley’s layout changes, and the Melbourne-Sydney battle shifts further into commercial overtones, then we risk raiding the tapestry of history for a ledger of numbers.

The changing track of memory

So here I am, not a habitual punter but an observer who has grown to appreciate racing’s deeper story. I’m not wagering the money, but I’m invested in the memory. I’m hoping that when the new Valley reopens in 2027, with the grandstand relocated, the straight longer, and the field bigger, it still feels like the Valley. I hope the two minutes it takes to run the Cox Plate still makes stars out of thoroughbreds. I hope the crowd still leans in, the bend still bites, the surge still murmurs through the rails, and the noise still pushes you.

Because Dave and Macca will still be in their fortress on Saturday afternoons, watching the form, still checking their tips, still remembering the battles of Bonecrusher, Winx and Might and Power. But will it feel the same for them? Will the markers of the past retain their meaning in a new layout? For Dave and Macca, therein lies both the grief and the hope.

Racing is, at its root, about time, space and myth. Change the time, widen the space, and the myth must adjust. The question for the Valley and for racing generally is: will it adapt, or will we bid farewell to the old magic? I lean toward adaptation, but I reckon Dave and Macca will miss what was. No doubt they’ll be watching. Because in the end, it’s not the bets that matter, it’s the stories. And if the Valley loses its story, we lose something deeper than a racecourse. We lose a stage where our champions became legends in just two minutes.

Exquisitely written. Meticulously researched. Superlatively presented. Robert Onfray, your prose carries a reader from ambiguity to revelation with relentless momentum. Like being on a horse at the races…

Like any sport, it’s not always the game, the action, or the race, but the history that’s been formed over many years.

What you have written in this article is a reflection of history that has been slowly built up over many years , which is the other side of this great sport quite often overlooked by the modern day race goer and punter.

Let’s just hope that the history, mystery of this classic WFA World Championship continues the W.S. Cox Plate tradition for many years to come.

Thank you Robert, and hopefully you’ve reminded your readers that this industry is not all about the punt.

Great story. Racing again brought to life.

Finally, a racing article written with genuine knowledge and feeling. So much so, that even though I didn’t have time when it arrived in my messages sent to me by a good mate, I couldn’t stop reading it until I got to the end!!

You may not have ever been “hooked”; however, your research and writing suggest that you “get it”. Thanks, Robert.

Unfortunately, I belong to that much-maligned group of industry participants who still remember all the good (and not-so-good) old days. Those of us who lived through it, worked through it, and remember fondly most races as if they were yesterday.

History. What history?

Today’s so-called racing journalists could learn a lot from your article.

Great job.

Well written. It will be interesting to see how the Valley is redeveloped.

The Valley, as it is universally and affectionately known, pioneered racing under lights in Victoria. With other racing complexes being developed in Melbourne, it will have to become more than just a racecourse hosting the Cox Plate to maintain its popularity. But the memories and stories will always be there.