For centuries, timber has been the backbone of human progress, building homes, fuelling fires, and shaping cities. Few of its many applications are as overlooked yet profound as the humble wooden paver. These blocks of timber, placed beneath the wheels of horse-drawn carriages and later automobiles, not only quieted the clamorous streets of bustling cities but also symbolised a harmonious partnership between nature’s bounty and human ingenuity.

Nowhere is this story more vivid than in Western Australia, where jarrah—known as Swan River mahogany—rose to prominence. More than just paving stones, jarrah blocks embodied the foresight of foresters whose sustainable practices ensured a seemingly endless timber supply for global markets. This is the tale of how wood paving transformed urban landscapes and what it reveals about our evolving relationship with the forests that sustained it.

Take your mind back to the nineteenth century, a time before motor vehicles when horse-drawn carts dominated land transport. The sounds of hooves striking cobblestones were the soundtrack of daily life, but these traditional road surfaces had significant limitations.

Roads constructed from broken stone and overlaid with ironstone, popularised by pioneers like Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam, offered smoother rides but wore out quickly under heavy loads. While cobblestones were durable, they were also noisy and harsh on horse-drawn carriages. Furthermore, dirt roads frequently turned into quagmires during rainy weather and generated clouds of dust during the dry seasons.

As cities grew, engineers sought better solutions for road surfaces. Wooden pavers emerged as a promising alternative, producing quieter, cleaner, and more durable options. Among the various timbers available, jarrah, sourced from Western Australia, distinguished itself with its resilience and longevity, becoming a prized timber across the British Empire and beyond.

Wooden pavers offered a quieter and smoother ride, reduced noise, minimised dust, and were durable and easy to clean. Additionally, they had a more attractive appearance, and Australia had an ample supply of strong hardwood species that could fulfil these needs.

The Global History of Wooden Paving

The origins of wooden paving can be traced back to early 19th-century Russia. In St Petersburg during the late 1820s, engineer V.P. Guryev developed hexagonal wooden blocks for road construction. These blocks were approximately seven inches high and ten inches in diameter. While the specific species used by Guryev is not documented, it is plausible that locally available species, including hardwoods such as oak, birch, and elm, were crafted for the job.

Wood paving gained popularity in England by 1839 and North America a year later, driven mainly by the public’s demand for quieter streets. Early trials in London, such as John Finlayson’s experiment outside the Old Bailey, were inspired by designs from St Petersburg. London’s damp climate shortened the lifespan of less durable timbers, such as fir and pine, that were prone to rapid wear. This led to a poor reputation for wooden pavers, prompting engineers to search for better alternatives. In 1843, granite setts from Scotland became the preferred option for London’s streets despite their noise.

Similarly, the use of softwoods in America also harmed the reputation of wood paving, as unsatisfactory results and poor installation contributed to its failure.

In 1869, almost 30 years after the original wood paving experiments, Threadneedle Street in London was paved with compressed asphalt. This new material quickly gained popularity among the public because of its quiet and smooth ride. However, horse owners dislike it because it is slippery, even when slightly wet. Soon after, most streets radiating from the Bank of England were asphalted. However, due to the high cost of asphalt, granite blocks remained in use despite the complaints about their noise.

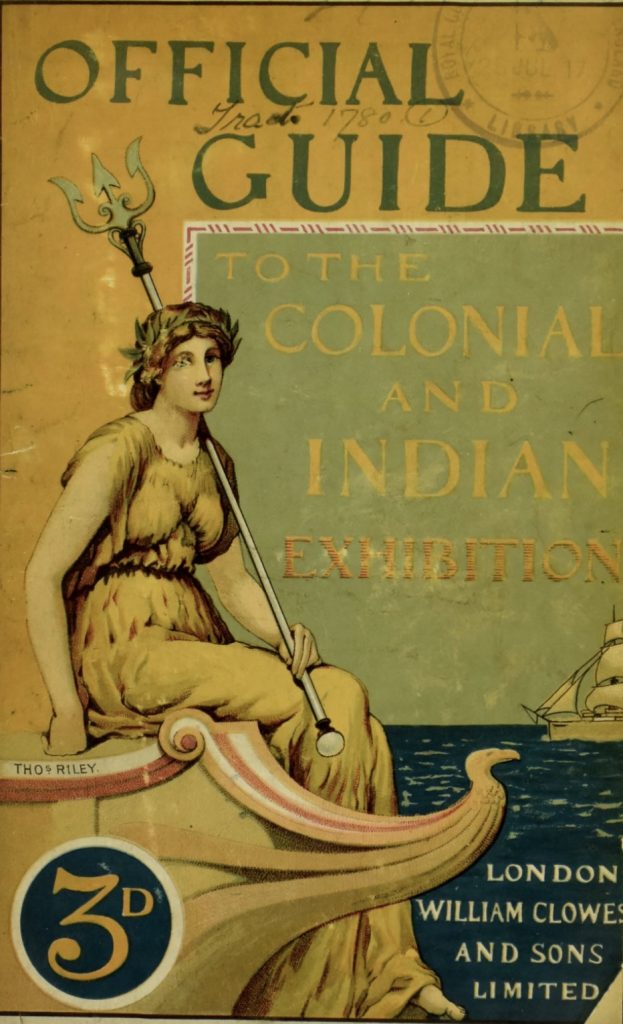

A breakthrough occurred in 1886 at London’s Indian and Colonial Exhibition, where premier timbers from Western Australia, such as jarrah and karri, were showcased. Jarrah’s exceptional durability impressed engineers, and within a decade, jarrah pavers were widely adopted in London boroughs such as Camberwell. Other Australian hardwoods, like river red gum, were tried but did not perform well over time and were replaced by jarrah. After years of heavy traffic, many jarrah blocks remained serviceable, reinforcing their reputation as a world-class material.

The Rise of Wooden Paving in Australia

Wood paving was first considered in Australia in the early 1840s, but substantial use didn’t occur until 1867 in Echuca, northern Victoria. Using locally abundant river red gum, these early efforts addressed the challenges of providing durable, low-maintenance roads for horse-drawn traffic. However, detailed records confirming this early use of wood paving are scarce and may not be reliable.

Years later, as Sydney and Melbourne expanded, engineers sought better road surfaces to accommodate increasing traffic. The number of buggies and horse-drawn carriages surged, and their steel shod shoes required a firm and stable surface for good traction. Residents and shopkeepers disliked the noise, dust, and mud associated with cobblestone and macadamised roads. However, the primary concern for engineers was the frequent wear and tear.

In 1880, when Sydney’s Improvement Committee requested a report on laying some streets with wood pavers, the city’s engineer, Adrien Mountain, initiated trials of wood blocks on King Street, between George and Pitt Streets. Mountain used Australian hardwoods such as river red gum, blackbutt, and Tasmanian blue gum. Some softer imported woods like cedar, brown pine and Baltic pine were also tested but proved unsuitable for heavy traffic. Although the durable ironbark species seemed an ideal choice, it was limited in availability and supply and cost 20 per cent more to procure. Tallowwood, grey gum and turpentine were later added as test species.

Two years later, samples of wood blocks were assessed for wear and tear, revealing that river red gum, Tasmanian blue gum and blackbutt were the most durable. Over the next three years, George, William and Castlereagh Streets sections were paved with various experimental wood block layouts.

Mountain’s method involved laying the wooden blocks on a concrete base, initially with ¾-inch joints. Over time, the gaps were reduced to ½ inch and eventually to 3/8 inch to prevent the blocks from creating a noisy corduroy surface under horse hooves. By 1882, woodblocks proved their durability and reduced maintenance costs compared to macadamised roads.

Melbourne followed suit, trialling wood pavers on Spencer Street and Collins Street in 1881. Favoured species included Tasmanian blue gum, Gippsland grey box, and river red gum, all known for their strength and durability. Kauri pine was also used. While not a hardwood, it formed an excellent roadway, making it more durable than the softwoods used in Europe and America.

A report from 1892 on the streets of Sydney found that blackbutt and tallowwood were the most durable wood blocks. It was observed that blocks laid with their ends butted together produced less noise from horse hooves, and there was no advantage in laying angled patterns over square blocks aligned with the road axis. Moreover, wood-paved roads were at least ten per cent cheaper than macadamised roads. Their main advantage was their minimal maintenance, with a lifespan of at least 30 years.

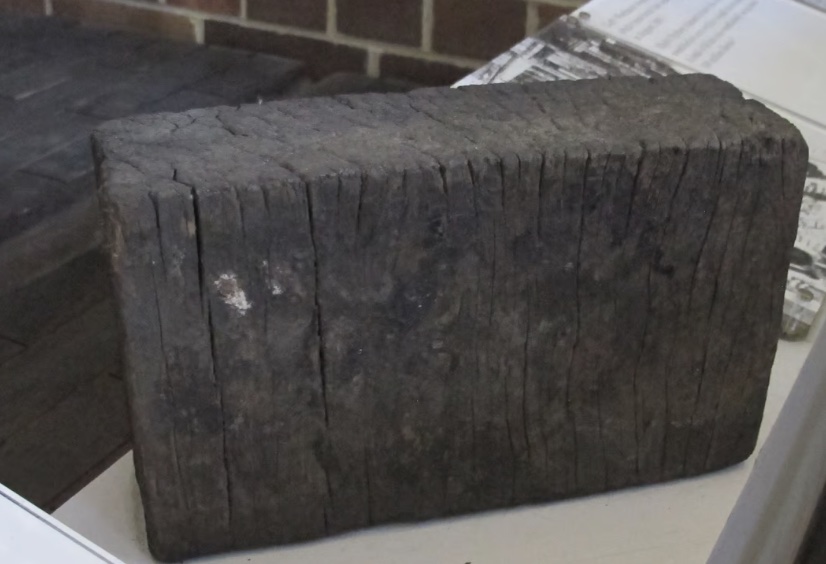

The wooden blocks were shaped like bricks and laid in a stretcher bond pattern. The surface was treated with tar, pitch, and pea gravel and sand to create a firm surface and enhance traction.

Each wooden block was sawn into six-inch lengths from 9 x 3-inch planks. While four inches would have sufficed, six inches was preferred because when the tops of the blocks wore down, they could be cut down to four inches and re-laid.

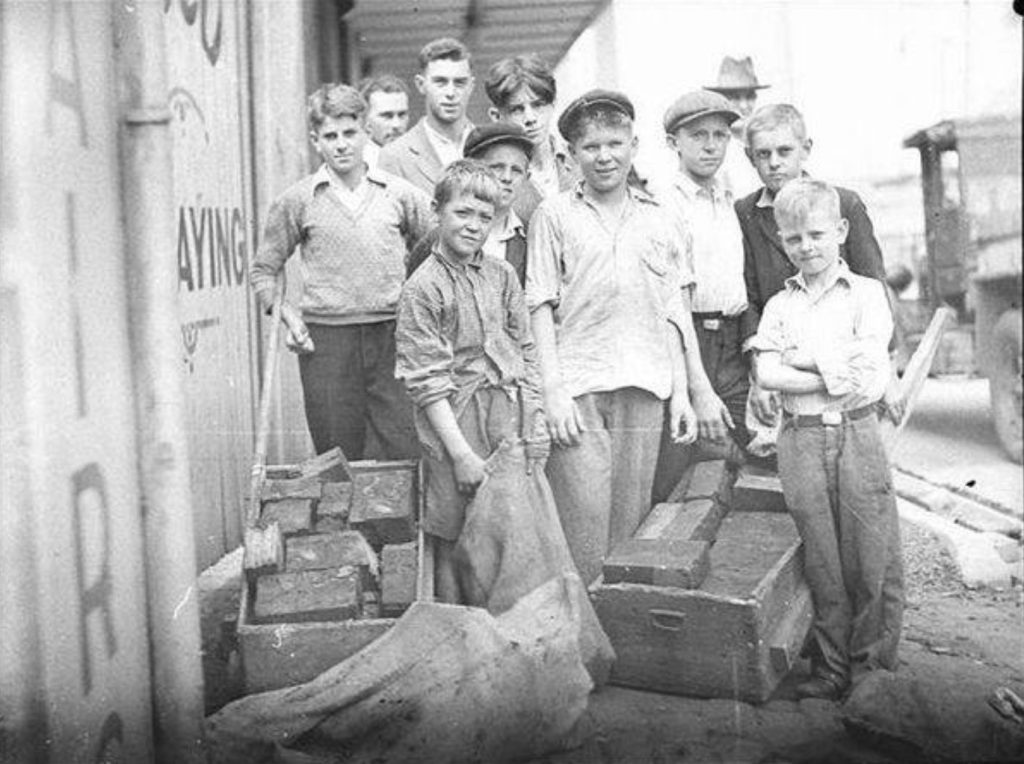

Each night, the wood blocks were washed down with disinfectant to reduce the risk of disease. During the day, “block boys” were employed to pick up rubbish and horse droppings to also keep the streets clean.

Mountain’s book titled Wood Paving in Australia, published in 1897, indicated that Melbourne had 112 acres of wood-paved streets compared to Sydney’s 103 acres. However, by the early part of the next century, Sydney had surpassed Melbourne. By 1912, it boasted the world’s largest area of wood-block roads, covering 148 acres and utilising an estimated 100 million blocks.

Nearly all the principal streets in the main central city were wood paved as well as heavily trafficked streets in Ultimo, Pyrmont, Surry Hills, Redfern and Camperdown.

While there is no evidence that Sydney streets were paved with Western Australia’s jarrah among all the timbers chosen, jarrah and red gum were the favoured blocks in Melbourne.

Jarrah’s Role in Fremantle and Beyond

In 1891, when Sydney was paving its streets with river red gum and “some lighter woods obtained from Queensland”, Perth was using an inferior combination of rotten mud and unsightly shells from the Swan River for its streets, neglecting the much superior timber available from the nearby forests.

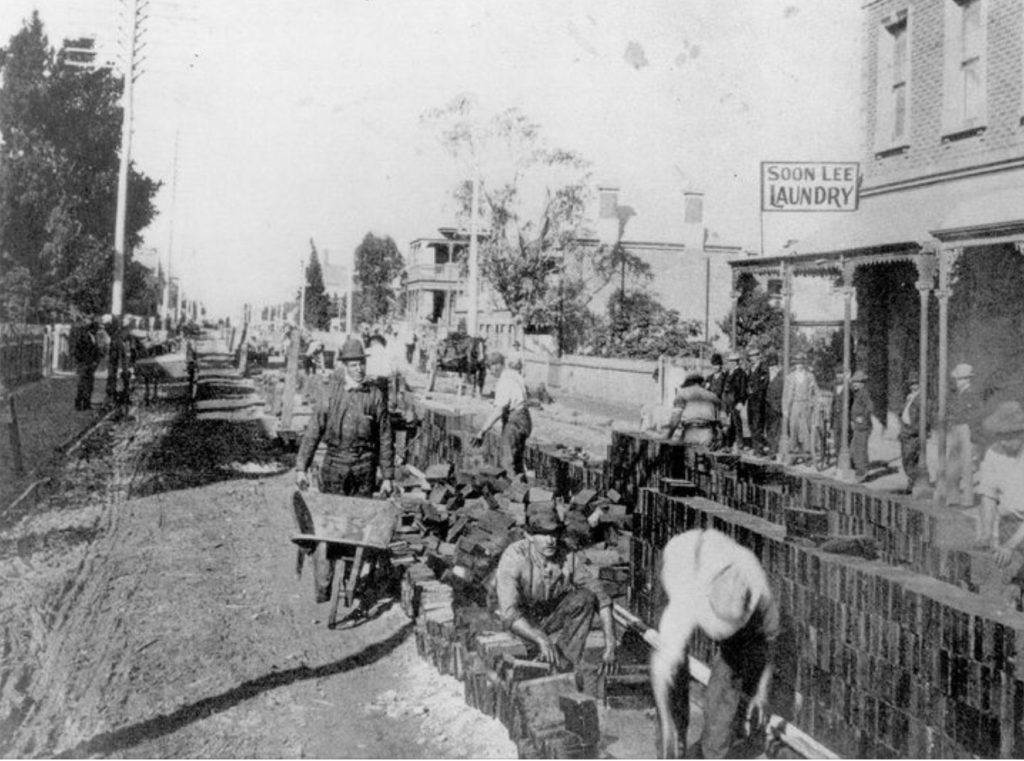

Perth began using jarrah in 1898 when Fremantle began paving streets, such as High Street, with jarrah blocks. Due to its proximity to timber sources and jarrah’s remarkable durability, it became an economical choice. Fremantle’s early adoption showcased the timber’s potential, and the port city became a hub for exporting jarrah blocks worldwide.

The laying of jarrah blocks in Fremantle wasn’t merely roadwork – it was a precise art. Workers meticulously arranged the blocks in stretcher bond patterns, ensuring durability and visual harmony. Each block carried the promise of decades of service.

Before the end of the nineteenth century, jarrah quickly became one of Western Australia’s most significant exports. This dense hardwood was used in road construction, railway sleepers, bridges, and wharves. The jarrah export boom coincided with the expansion of the British Empire, which required durable materials for its global infrastructure projects. Timber mills in Western Australia worked tirelessly to meet the demand, processing logs into uniform pavers for shipment.

Jarrah’s global reach reflected its unmatched qualities as cities in Europe, Asia, and North America experimented with jarrah road paving. Its reputation for longevity and resilience ensured steady demand, making it a cornerstone of Western Australia’s economy as it became the timber of choice for not just streets but also railway sleepers that spanned empires.

The demand for jarrah was so immense that London firms decided to buy the timber companies in Western Australia that held logging rights and already possessed the necessary infrastructure. These timber companies were financed by capital out of London, and recent price cuts had affected their profits and the continuation of the industry.

Millar’s Karri and Jarrah Forests Limited was a public company incorporated in July 1897, and its shares were listed on the London Stock Exchange. The directors noted the sizeable profits made by those supplying nearly 50 miles of jarrah paving on London’s high-end streets: Baker, Oxford, Regent, Bond, and The Strand. They organised the amalgamation of nine timber firms in Western Australia to focus on harvesting jarrah.

Millar’s were determined to ship every jarrah stick they could obtain to London. By controlling the supply of jarrah in Western Australia, they could meet the demand and reap significant profits.

The decline of wood paving

Wooden paving began to wane in the early 20th century as motor vehicles replaced horse-drawn transport. Increased vehicle speeds and heavier loads caused significant wear and tear on wooden blocks. Additionally, wooden streets absorbed stains and odours, particularly from horse urine, despite regular cleaning and disinfecting. These drawbacks, coupled with the advent of asphalt and concrete as cheaper and more durable alternatives, marked the end of wooden pavers.

In Sydney, wood paving ceased by 1932 during the Great Depression, although wooden blocks remained in use for some roads until after World War II. Many old blocks found new life as firewood, particularly during economic hardships when young boys scavenged them to heat homes and cook meals.

Jarrah’s legacy

The story of jarrah pavers reflects the ingenuity of 19th-century engineers who developed practical solutions for urban development. From Fremantle to London and even Berlin, jarrah’s global reach underscores its unmatched qualities as a durable and versatile hardwood. Today, remnants of these streets serve as historical artifacts, reminding us of an era when timber paved the way for modern cities.

While softwoods like pine crumbled under the demands of bustling streets, jarrah blocks held their ground, enduring decades of relentless traffic without losing their shape or integrity. Today, remnants of jarrah-paved streets whisper stories of a time when Western Australia’s forests fuelled the ambitions of an empire. These blocks, weathered yet resilient, remind us of the bond between human ingenuity and nature. This bond was sustainably managed by foresters, whose professional care ensured a timeless supply of timber for the market.

It is not surprising that jarrah is held in such high esteem. It is a beautiful and versatile timber with many applications. Jarrah has been used in house framing, flooring, weatherboards, fences, piles, and decking on wharves and jetties. Additionally, it has served as railway sleepers, dance floors, parquetry, fruit cases, wooden ships, window frames, balustrades, decking and furniture, including desks for parliamentarians in the new Parliament House.

Experienced Western Australian forester Roger Underwood notes:

Polished jarrah has a deep inner glow, superior to mahogany and as good as red cedar in my opinion. The dark red and brown colours survive in jarrah kept indoors.

Looking back, jarrah’s contribution to infrastructure emphasises the value of timber and its environmental benefits. Its use in railway sleepers is a prime example, as these durable wooden components not only supported transportation networks but also sequestered carbon for decades – an ecological benefit unmatched by the concrete that replaced them.

Tragically, this dual legacy has been largely disregarded by many in Western Australia, where the battle to end native forest harvesting was won at the cost of opportunity. The chance to manage hardwood forests sustainably, balancing innovation with preservation, now seems lost perhaps forever. With the forests locked away and timber utilisation curtailed, a vital connection between people and their natural heritage risks being forgotten.

It doesn’t have to be forever. The common sense, beauty and sustainability of the industry will make plain sense in the future.

Thanks Robert for another fascinating essay. Timber, with its many uses, was and can be a truly sustainable product. Pity politics (not science) has seen the demise of the native forest timber industry.

Thanks Rob for this article.

I had not known that this was an early day practice, but I am not surprised that timber pavers were used in road construction considering the durability and hardness of these timbers.

Another well-researched article.

Wonderful story, Robert. It’s tragic that sustainable jarrah harvesting was stopped in WA by the McGowan Labor government, purely for political expediency.