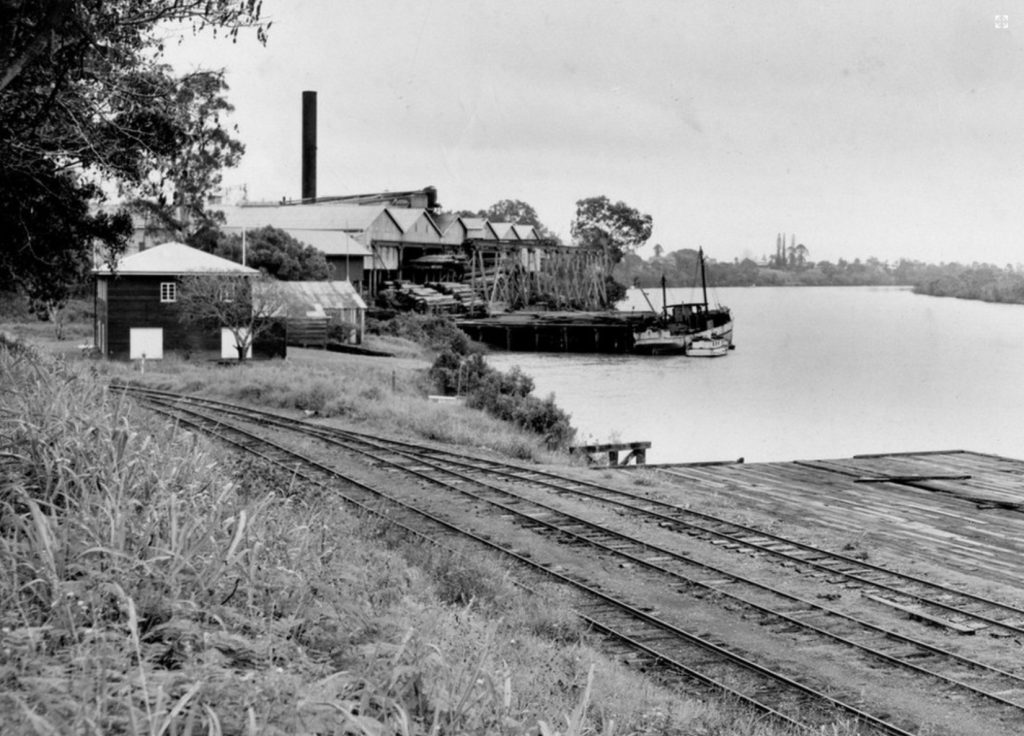

Before four-wheel drives began churning through Fraser Island’s sandy tracks, before tourists arrived and the World Heritage listing was established, the timber industry thrived. Tall, straight blackbutts, satinays, and tallowwoods rose from the sandy soil, destined for sawmills across the strait in Maryborough. The unglamorous, hardworking punts carried the weight of this industry, one load of logs at a time.

Between the early 1870s and the early 1990s, the Great Sandy Strait functioned as the logging trade artery for Fraser Island. With tides as their timetable and weather as their foe, a small fleet of punts and their operators, known as puntmen, undertook the risky voyage time and again. Their lives revolved around tidal strategy, engine grease, bush ingenuity, and fending off sandflies that some claimed bordered on the insane.

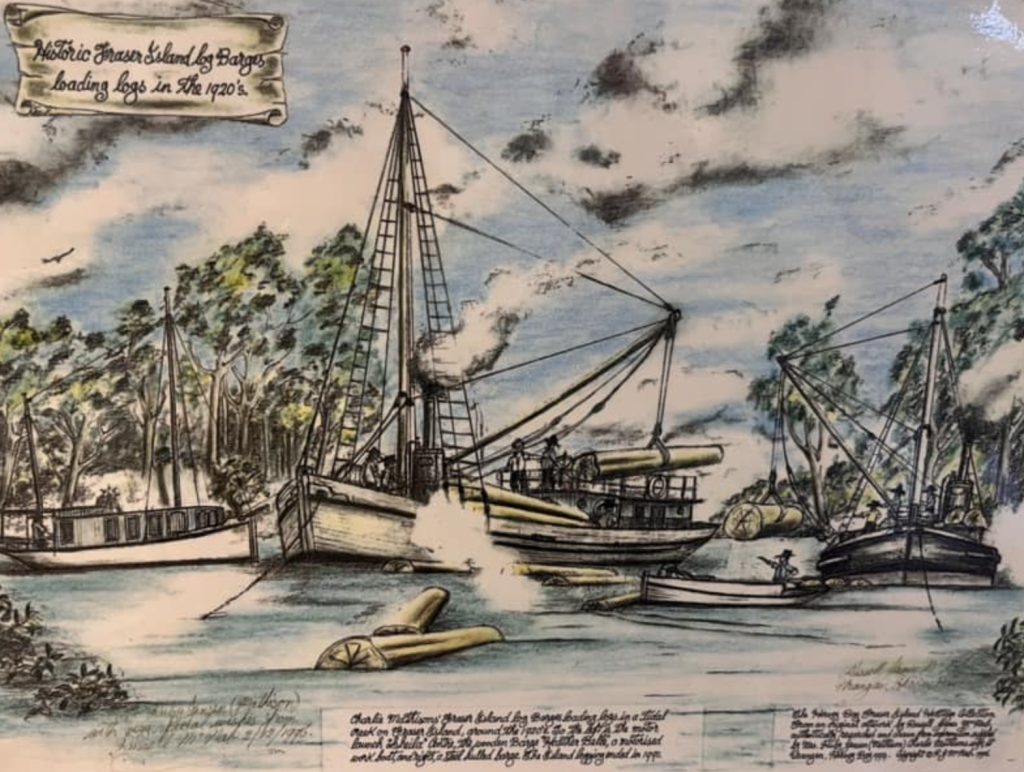

The Silent Barges of the Strait

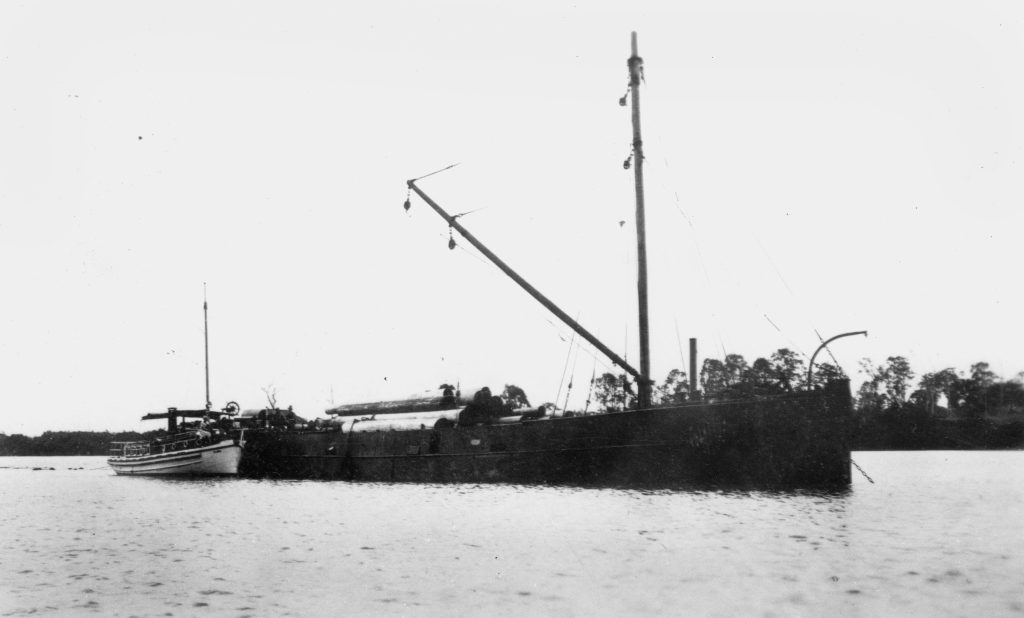

Originally steamers or grain carriers, the punts were often stripped of their engines to comply with a little-known 1902 regulation that prohibited steam-driven boats from transporting logs under their own power. Thus, they became true workhorses of the sea—hulking, engineless barges towed by launches with names like Dagmar, Sheila, Noosa, and Kirawan, Trade Winds and Sylvan.

One of the most storied puntmen, Charlie Mathison, could be seen towing up to three punts at a time, dropping them off at various log dumps along the island’s western creeks, before collecting them again once loaded. He owned many punts, including Muriel Bell, the wooden Maria, the iron Maria, Swordfish, Heather Belle, Friendship, and Palmer.

The Palmer had a somewhat celebrated career. In 1935, the Burrum Shire Council decided to seal the Esplanade between Urangan and Point Vernon. The gravel deposit along the western beach of Woody Island (unlike Fraser, it is not a sand island) was identified as suitable for the road base, as the stones were already cemented together by the acids that percolated through the gravel bed.

Mathison won the contract to supply gravel from Woody Island, using the Palmer and the iron Maria. The former was an ex-passenger mail and cargo ship based in Townsville. Built in 1884 in Scotland, she was originally a twin screw, 267-ton steamer, measuring 43 metres in length. The Maria was an ex-navy vessel from World War I.

When that roadwork contract was completed in 1937, Mathison turned to transporting logs from the island and taking vehicles and horses there. Mice and rats were a menace, particularly when they came aboard using the mooring ropes. Mathison had a pet python on board to keep the rodents under control.

The Palmer ran until World War II, when the navy decided to use wartime powers to take control of the boat for its own purposes. Mathison, however, would have none of that, so he beached the vessel in Deep Creek and holed her hull with an axe. The remains are still hidden in the creek, surrounded by the march of the mangroves. Mathison continued his business using the Essex.

Each punt carried not only logs but also firewood, water tanks for the winch boilers, and enough provisions to withstand delays caused by tides or inclement weather. Punts were steered into mangrove-choked creeks during high tide, where they would wait for low tide to rest on the creek bed. Only then could the steam-powered winches begin hauling the massive logs aboard. If a punt remained afloat while being loaded, the shifting weight could cause it to list dangerously, making the operation both risky and exhausting.

Pioneers and Personalities

Charlie Mathison’s father, Christie, and his brother Matthias were pioneers of the Fraser Island punt scene, starting in the 1870s. They transported logs from the island using sturdy, flat-bottomed wooden barges propelled by long oars known as sweeps, the primary one being the Slave.

They also mined sand at Deep Creek to supply mouldings for Walkers Limited in Maryborough. The sand was ideal for casting iron, steel, bronze and aluminium mouldings as it set hard when dry. The sand was mixed with linseed oil and bentonite, placed into a mould, and baked to dry and harden. Each mould could only be used once, as it was necessary to break it to remove the casting. The broken mould was processed through a machine to grind the sand so it could be retrieved and reused.

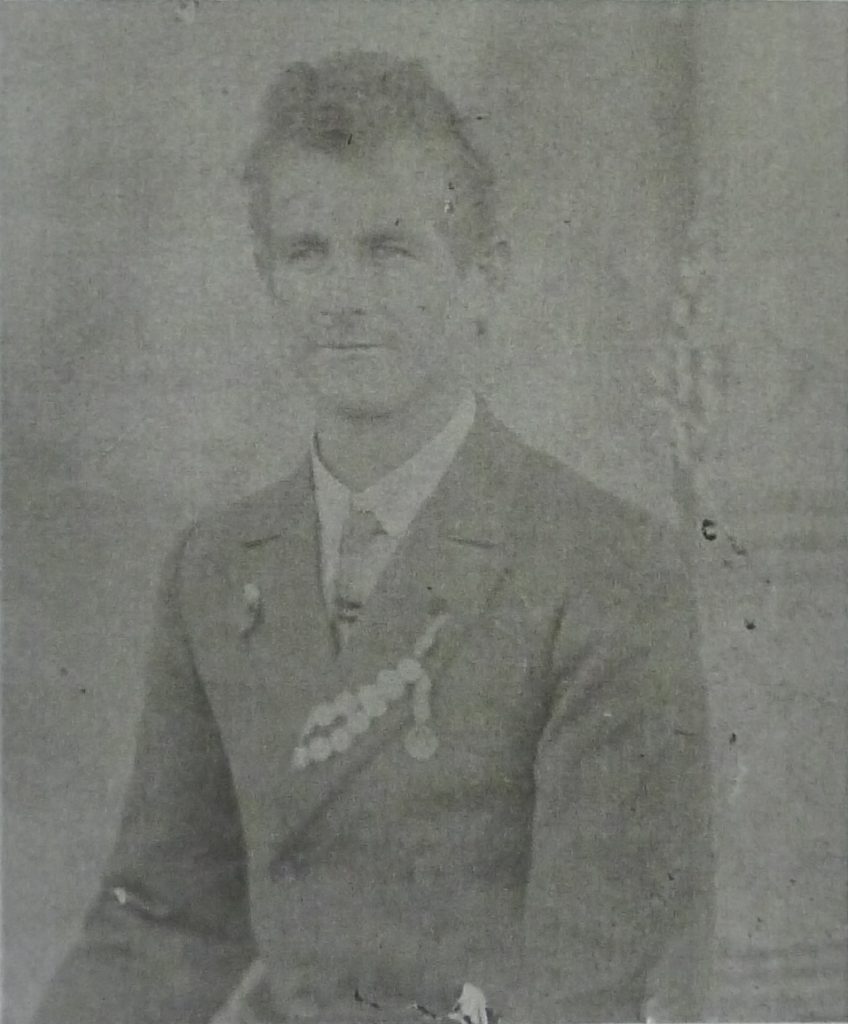

One of the earliest characters in this maritime world was Edward “Ned” Armitage. By 1905, Armitage was skippering a punt called Geraldine, carting timber from Fraser Island to the mainland with the help of his deckhand, a wiry local named Frank “Bendy” Webber. The Geraldine was no pleasure boat—wooden-hulled and stubborn, she required constant attention. She ran until 1911, when she was lost near North White Cliffs. Undeterred, Armitage joined forces with Webber to commission Geraldine II—a larger, tougher vessel for a trade that demanded nothing less.

Armitage belonged to a generation that navigated not only tides and creeks but also the early, lawless days of the industry, where extracting timber from the forest was half the battle—and transporting it across the Strait was the other. He embodied the resourcefulness of early puntmen, who made repairs on the fly, cooked in oil drums, and navigated as much by instinct as by chart.

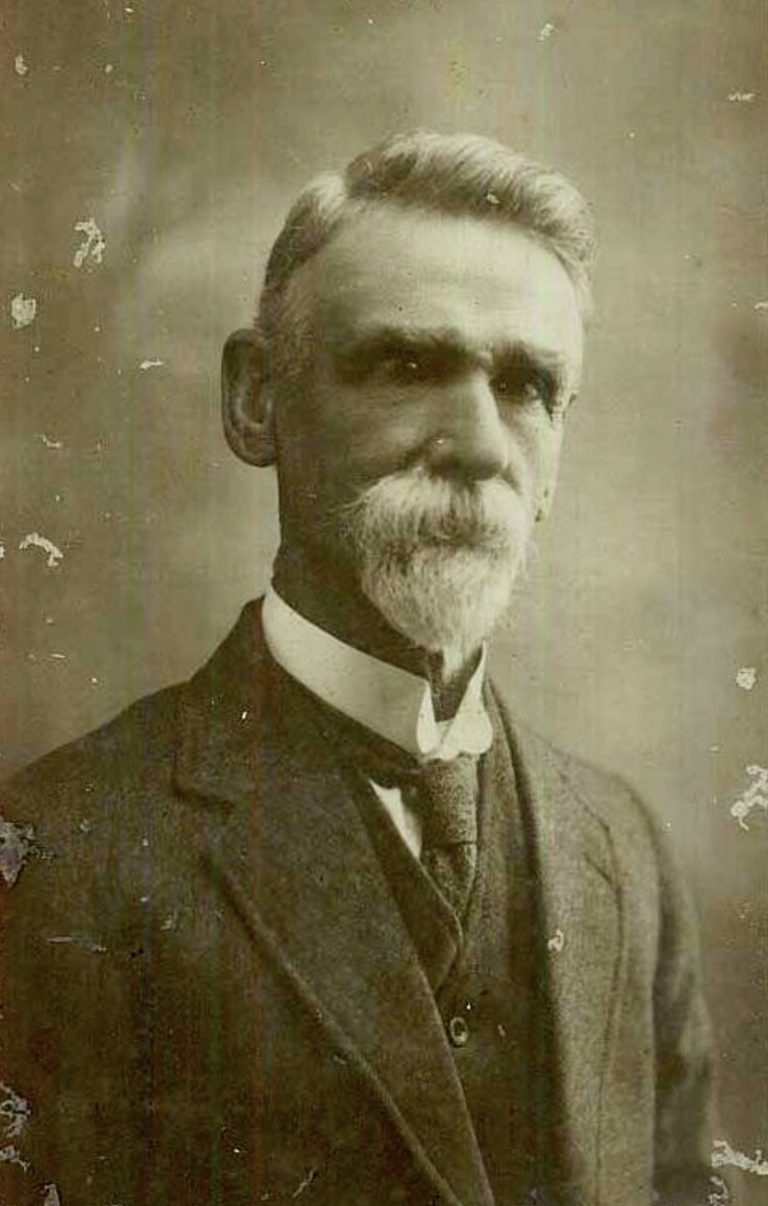

On the other end of the era stood Allan Shillig—one of the last puntmen. Allan delivered logs to the Hyne and Son mill, starting on K’Gari in 1965 and continuing until its retirement in 1976, spending his last year as skipper. He then captained the Hopewell, a purpose-built steel-hulled punt launched in 1976 that could carry 300 tonnes of logs and was the largest of all the punts. Unlike the timber and iron relics of earlier decades, the Hopewell was a modern workhorse constructed in Brisbane for nearly half a million dollars.

Yet, even modern engineering couldn’t ease the hardships of the job. Shillig recalled the relentless sandflies that plagued the mangrove creeks. He wrote in his wonderful book, The Last Fraser Island Puntman:

On some bad days, you swallowed them by the mouthful every time you breathed in.

In the early days, there was no repellent, just smoking pots of cow dung or old rope, and a desperate hope that the wind would change. His descriptions echo those from the 1920s when men at North White Cliffs doused themselves in kerosene at night to fend off fleas.

Shillig came from a family of mariners. His father, Des, was the skipper of the Pelican, a self-powered but smaller punt that plied its trade across the Great Sandy Straits. His brother, Larry, also worked with him on the punts.

Shillig persisted and was truly the last of the puntmen. Hopewell transported its massive loads across the Strait until the final weeks of the Fraser Island timber trade. On a muggy day in late January 1992, Shillig oversaw the last shipment of logs from Fraser Island. It marked a quiet, understated end to over a century of maritime industry. There was no ceremony, just another tide caught and another crossing made.

A Floating Fleet

The names of the punts are just as memorable as the blokes who worked them: Josephine, Lass O’Gowrie, Otter, Goori, K’Gari, and Island Trader.

The steam-driven Otter, built in 1923, was originally known as Gartmore and later as Goondi. When she became unfit for coastal trade, Wilson Hart removed the steam engines after they acquired her in 1949.

She was fondly remembered by families connected to her. Lynnette Comfort recalled standing in the wheelhouse with her grandfather, skipper Frank Fushs, in the 1950s, her eyes barely reaching the helm.

The twin-hold vessel Lass O’Gowrie was purchased by Wilson Hart in 1938 and operated until 1967, when she was beached in the mangroves on the southern side of Bogimbah Creek until her removal in 1973.

K’Gari, like many of the punts, began her life as a naval vessel or sugar carrier. Built in 1897, she served in the navy during World War II. In 1954, she was purchased by Hyne and Son, converted into a logging barge, and skippered by Cliff Sanderson. She was remarkably industrious, transporting 839 loads of timber from the island in her 22-year tenure. Hyne and Sons’ smaller vessels – Pelican and Kundu – provided support for her.

The former was owned by the Berthelsen brothers – Tom (Jnr) and William. They bought it from the Adelaide Steamship Company in 1941 and sold it to Hyne and Son when they dissolved their partnership and finished logging on the island around 1944.

The latter, co-owned with Wilson Hart, was originally the supply vessel for the Moreton Bay Lighthouse and was briefly used by Walkers Limited to transport moulding sand from Bun Bun Creek on Fraser Island. Barry Seymour and Vince Knott skippered her during her short time as a timber punt from 1967 to 1976.

Boral began operating a sawmill in 1986 on Pulgul Street, Urangan, after acquiring Wilson Hart’s quota following its demise. Initially, they transported logs from the island, but their punt wasn’t large enough to carry a sufficient load. Nick Schulz was given a twenty-five-year contract to transport logs to the mill. He purchased the twin-hold ex-bulk carrier Skode and converted it to accommodate the changing tides in Pulgul Creek, renaming it Island Trader. With Dennis Christopher as skipper, she carried logs from Garry’s Camp, Puthoo Creek, and Poyungan Creek for four years until logging on the island ceased at the end of 1991. Boral also operated the single-hold Stockton as a punt, both towed by the tug Sylvan.

After their working lives ended, many punts were beached or scuttled. Otter, Goori, Pelican, and Lass O’Gowrie now lie beneath the waters of the Roy Rufus artificial reef, the subject of a future blog. Goori was the last to be scuttled on the artificial reef in 1990. The ageing hull had been stuck on a mudbank inshore behind the Brothers Islands on the Mary River about halfway between Maryborough and River Heads. It had been the centre of an ownership wrangle for more than three years.

Josephine was owned by Webber and is thought to have originally served as an ice or grain carrier. Her iron hull was lined with concrete, wooden slats, and straw to cushion the cargo. Webber abandoned her in the mangroves of Poyungan Creek in January 1940, where rust and sand slowly claim the iron hull.

The Last Tide

By the late 1980s, the end was in sight. Yet, even with improved technology, the tides—and environmental momentum—were turning.

At the end of 1991, logging on Fraser Island officially ceased. The final voyages of the Hopewell and Island Trader marked the last loads by the end of January 1992. With that, the punts vanished from the Strait, and an era concluded not with a splash, but with the silence of the last wake fading behind the stern.

Terrific story. Written so well, I shed a tear at the end.

Is it the Josephine or the Auburn in Poyungan Creek? I think it’s in Fred Williams’ “Princess K’gari” book as the Auburn.

Andrew

My notes indicate that the Auburn, also owned by Frank “Bendy” Webber, was scuttled in Poyungan Creek along with the Josephine. I don’t have much information on the operation of the Auburn.

Robert. A most excellent blog. Always enjoy the read. John

My dad, Cliff Sanderson, and his father, Joe, operated the Lass O’ Gowrie towed by the Trade Winds for the Wilson Hart sawmill. Joe Sanderson owned it, and later my father. I do have some of its earlier history and photos compiled by my brother Marshall before his passing.

The Lass O’ Gowrie was sold to Wilson and Hart in 1956. My dad then went on to operate the K’gari towed by the Elma. I had many school holidays spent on these vessels. My dad passed away in 1965.

Another great read Robert – people don’t appreciate the hard work and perseverance that underpins a lot of the wealth of the baby boomer generation. And the resistance to Govt dependency which is sadly lacking now in any sort of rational sense.

Thank you!

A very interesting read, Robert.

As my parents and grandparents were involved in the logging and making of the roads over Fraser, it was heartwarming to hear of old, familiar friends who have passed away now.

I look forward to reading more.

Thankyou,

Narelle Luck (Evans)

Was the new name of the island taken from this boat?

Gary,

The current name originates from the Butchella name for the island, K’gari, meaning ‘paradise’. It is most likely the other way round – the name of the vessel came from that.

Ok that makes sense

Another interesting read Robert, thankyou.

Hi Robert, My Dad’s name was Allan Kuskie. You mentioned a couple of his boats.

Geraldine – Dad bought Ned Armitage’s Geraldine (sometimes known as Geraldine II) in 1937.

She was anchored at Boonooroo at the time. There were 2 vessels named Geraldine, the other a log punt.

Dad used to bring white sand from Deep Creek to Walkers for use in the Moulding shop. There are many photos of the extended family loading sand at Deep Creek and also aground in the river with all the family on the shovels loading sand.

The Geraldine was very well known in Ned Armitage’s day.

When war broke out, Dad and crew patrolled the Sandy Strait looking for Japanese submarines. They had one gun.

Essex, another of Dad’s. I have a licence dated 1945. I don’t think Dad used Essex much, as he did not speak of her as much as the others. The register closed in 1956 after the ’55 flood. The remains of the Geraldine II and Essex lie in the Mary River at Brisk St, where Dad had his sand and gravel business.

He also punted logs in the Endeavour around 1934 from Poverty Point. He would have been 22.

Best wishes, Rita Stephensen

Robert, congratulations on another well-researched article, which captures some of the 150 years of logging and forestry on Fraser Is.

Unfortunately, National Parks and the Government seem bent on hiding the logging history. Central Station’s history is barely mentioned.

Norm Clough

Excellent potted history.

Thanks Robert.

Another excellent and valuable historical account Robert, complete with lots of great photos I have never seen before. Can I sense another book in the writing?

Thanks, Ian. If the book sells well and there is genuine interest in my stories about Fraser Island, I can definitely look at collating them into a book.