Some say Australia runs on prawns, and during our travels around Australia, I saw a hint of truth to that statement.

The prawn has come a long way from humble beginnings in the shallow waters of Sydney Cove to vast aquaculture farms in Shark Bay and bustling trawler fleets off Karumba. My own journey retracing this crustacean’s commercial legacy took me from Queensland’s Gulf to Western Australia’s Indian Ocean shores, finishing on the familiar rivers of northern New South Wales. And somewhere along the Pacific Highway near Ballina, a giant fibreglass crustacean reminded me that the prawn isn’t just a popular food, it’s a national icon.

Where it all began: Sydney Cove and hauling nets

Australia’s prawn story began in the late 1700s, shortly after the arrival of European settlers. Fishing in the brackish waters of Sydney Cove, early colonists used scoop and hauling nets to catch king prawns from sandy bays and smaller “school prawns” in tidal rivers. By 1886, Port Jackson was reportedly “at its climax,” with over 100 boats engaged in prawning.

Still, these were small-scale operations. Without reliable ice or cold storage, the trade remained largely local. In fact, prawns often played second fiddle to more resilient species like crayfish, which performed better in Sydney’s early fish markets.

The Clarence and the cold chain revolution

The real leap forward came not in fishing techniques but in logistics. Before 1900, prawns from the Clarence River, which would go on to become the heart of New South Wales’ school prawn fishery, had to be iced with blocks transported from Sydney, limiting their shelf life and market reach. Hunter River prawns were shipped by steamers, with anglers making two horse-and-cart trips to move their catch to the wharves.

That all changed with refrigeration. As ice became more widely available in the early 20th century, prawns could be kept fresh for longer and shipped over greater distances. Suddenly, small regional fisheries had a pathway into Sydney’s expanding markets.

A net full of controversy

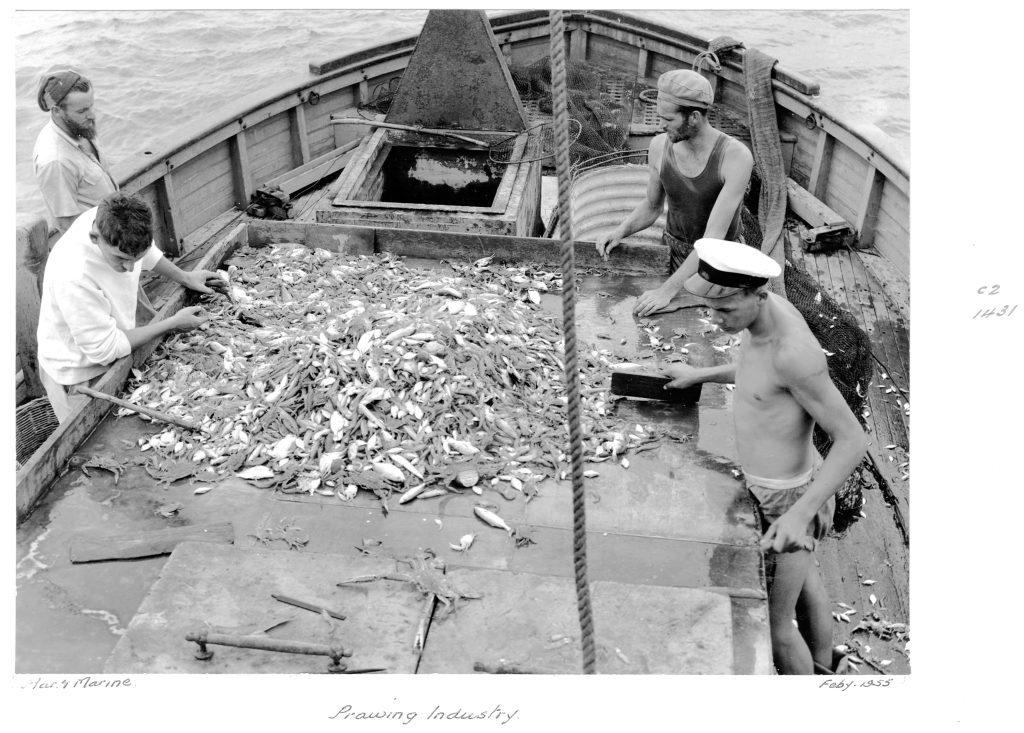

A game-changer arrived in 1926 with the introduction of otter trawling. Introduced into Port Jackson amid significant controversy, trawling opened up deeper fishing grounds offshore. Critics—especially traditional net fishers—protested that trawlers damaged weed beds and spawning areas while also interfering with commercial shipping. Despite the backlash, mechanised trawling quickly gained popularity and spread to Botany Bay, the Hunter River, and eventually, the Clarence.

These seabed-hugging funnel nets, held open by angled “otter boards,” have transformed coastal prawning into a significant industry. Ocean trawling surged after 1947, following the discovery of rich prawn stocks off Stockton Bight near Newcastle and further north off Evans Head.

Gulf gold

Fast-forward to our travels through Queensland, and we found ourselves in Karumba—the dusty end-of-the-road town where the Gulf of Carpentaria meets the sea. Karumba was buzzing during our visit, and the end of the wet season brought boats in and locals out to swap stories.

Karumba is known for its prawning activities, even though it was the last major prawn fishery developed in the state. When the whaling industry ended in the early 1960s, the CSIRO suggested that the Gulf of Carpentaria could serve as a valuable source of prawns. A survey of the Gulf was conducted between July 1963 and August 1965, revealing large schools of banana prawns approximately 32 km offshore.

Today, Karumba is where prawns are more than just a meal – they’re a livelihood. What began as exploratory fishing in the 1960s quickly evolved into one of Australia’s most productive and largest prawn fisheries. With their sweet meat and quick turnover, banana prawns are the region’s crown jewel. They are so named for their curved shape and yellowish hue – they represent big business up here. However, tiger prawns have increasingly become important due to the significant fluctuations in the banana prawn catch.

Here, the industry revolves around seasonal pulses. When the monsoonal floodplains empty into the Gulf, tens of millions of prawn larvae are flushed into coastal waters. It’s a boom-and-bust cycle that the locals know well. During good years, trawlers push out into the Gulf, pulling tonnes of banana prawns in just a few weeks, returning with loads that head straight to processing facilities or are trucked out frozen. It’s a tough life that has sustained Karumba for decades.

There’s a rugged charm to Karumba, and the prawn fleet gives it a unique pulse.

The rise of aquaculture

From the dusty tropics, we travelled back down the coast of Queensland to Victoria and then moved up through the centre to the Northern Territory. We continued across the top until we reached Western Australia. It is no slouch when it comes to prawns either. They have spearheaded the advancement of prawn farming as wild stocks approach ecological limits and environmental pressures increase. The CSIRO and industry stakeholders have collaborated to enhance hatchery techniques, manage water quality, and control diseases.

Eventually, the coastline led us to the turquoise waters of Shark Bay. Denham offers stunning coastal scenery, and it has become a hotspot in the next wave of prawn production, known as aquaculture. It is the kind of place where the sea laps at the edge of a slow-moving town, and seafood features heavily on every plate.

Carnarvon, located further south, has emerged as a key site for aquaculture. The waters off Exmouth and the Pilbara coast are teeming with tiger, king, and endeavour prawns. The prawn industry is high-value and tightly regulated, with the Exmouth Gulf prawn fishery recognised internationally for its sustainable practices. Carnarvon’s aquaculture ventures are a recent development, providing hope for a stable, farm-based supplement to the wild catch.

It’s a high-tech operation, yet it remains in tune with the rhythms of the land. Salinity levels, temperature variations, and even lunar phases affect growth rates. The result is premium-quality prawns that have a low environmental impact and are available year-round.

Aquaculture now accounts for approximately 50 per cent of Australia’s prawn production—an astonishing feat for a country that once relied almost entirely on wild-caught prawns harvested by trawlers.

South Australia’s hidden treasure

From the wilds of Western Australia, our journey led us across the Nullarbor to South Australia, where we spent time on the Eyre Peninsula, and what a revelation that turned out to be.

While Port Lincoln is renowned for tuna, it is also home to one of Australia’s most sustainable prawn industries. The Spencer Gulf prawn fishery, based out of Port Lincoln, Cowell and Wallaroo, targets the western king prawn. This fishery operates during short, carefully managed seasons in autumn and spring. Trawlers venture into the Gulf and return swiftly with their catch of flash-frozen prawns that are primarily exported to markets offering top dollar.

What impressed us most is the fishery’s approach. Strict quotas, seasonal closures, and a commitment to protecting marine habitats are hallmarks of this industry. The Gulf St Vincent fishery is closer to Adelaide than a smaller West Coast fishery that taps into the Eyre Peninsula’s remote waters.

The prawn industry here doesn’t promote itself loudly. However, it’s a subtle success story of clean, green prawns full of flavour.

The Big Prawn

Our coastal loop concluded on familiar territory – the north coast of New South Wales. I had lived and worked here in the early ’90s, and while revisiting the region, I passed by the iconic Big Prawn in Ballina once more. Towering over the old Pacific Highway like a crustacean colossus, the 9-metre-long concrete and fibreglass prawn has always been more than just kitsch.

Built in 1989 as a roadside attraction and a local tourism drawcard, the Big Prawn symbolised the significance of the regional seafood industry, particularly the Clarence River prawn fishery to the south. In its heyday, the complex featured a seafood market, souvenir shop, and restaurant. However, as the years went by, the Big Prawn lost its lustre.

Locals erupted when the local council approved plans for its demolition in 2009. This prompted a wave of support for the prawn, and the “Save the Prawn” campaign gained momentum. A petition circulated, and the national media covered the saga.

Ultimately, the prawn triumphed. Bunnings came to the rescue by agreeing to host the prawn at its new warehouse site. The restored, cleaned-up, and proudly re-erected prawn opened in 2013, complete with a massive new tail (the original was bizarrely tailless).

While Ballina itself never dominated the industry like Yamba or Iluka, the presence of prawns on the highway reminds every passerby of what the north coast represents with its rivers, seafood, and a strong sense of local pride.

From plate to export

Modern-day prawning blends traditional and contemporary methods. Traditional estuarine trawlers still operate in the Hunter and Moreton Bay, harvesting school and king prawns for the domestic market. Offshore fleets in the Gulf and Exmouth Gulf target banana and tiger prawns for both Australian and international buyers. Meanwhile, farms in Queensland, Western Australia, and northern New South Wales contribute more annually, supported by research and development, as well as consumer demand for traceable, sustainable seafood.

Prawn exports today exceed $300 million annually, with Asia being a key market. However, local demand remains strong, especially at Christmas, when Australians consume over 40,000 tonnes of prawns. That’s roughly two prawns per person each day for the entire month of December!

In recent times, things aren’t so bright for the prawning industry on the Clarence River. For much of the 20th century, the river supported a thriving prawn industry. Estuarine trawlers harvested school prawns while aquaculture farms produced tiger and banana prawns for the domestic and export markets. But in recent years, that legacy has hit a significant snag. In 2022, the white spot virus, a contagious disease affecting crustaceans, was detected near Palmers Island, prompting a biosecurity lockdown. As of 2025, the entire Clarence River remains closed to the sale and movement of uncooked prawns, and most fishing operations are suspended while the government conducts long-term surveillance and risk assessments.

Despite this, Clarence’s history as a key link in the cold chain revolution remains undisputed, and there’s strong hope among locals that one day, the nets will be back in the water.

A thread that ties the coast

What unites the Karumba, Carnarvon, Port Lincoln, and Yamba regions is a shared respect for the ocean and a reliance on both wild and farmed prawns. The industry has faced its share of challenges, including outbreaks of white spot disease in Queensland and on the Clarence, and environmental concerns regarding trawling. Yet it persists.

Modern prawn fisheries in Australia are among the most regulated in the world. Quotas, gear restrictions, marine park zoning, and aquaculture licenses are part of an ever-increasing regulatory management system. Yet despite these growing challenges, the industry benefits from coastal communities that have a deep connection to prawn fishing in their heritage.

We followed the trail with curiosity and anticipation, coming away full of admiration and, let’s be honest, prawns.

A national crustacean

As I sat by the river in Iluka on the final leg of my trip, watching a trawler cruise past in the fading light, I reflected on how far this little creature has come. The nets may be idle on the Clarence for now, but the legacy of prawning in these waters runs deep. From hand nets in Sydney Cove to aquaculture ponds in Shark Bay, from Ballina’s fibreglass monument to export terminals in Karumba, the prawn is woven deeply into Australia’s culinary and cultural fabric.

This story is more than just about seafood. It’s a tale of innovation, resilience, and identity. Whether grilled on a barbecue, incorporated into a curry, or served chilled with cocktail sauce, Aussie prawns are a national treasure.

My preference is served cold, accompanied by a squeeze of fresh lemon juice, a side dish of aioli and a cold beer. When I feel a bit adventurous, I enjoy purchasing raw prawns and grilling them on the barbecue with garlic and chilli, complemented by that cold beer.

What’s your preferred way of eating prawns?

Raw prawn meat cooked a minute each side in olive oil, garlic and dusting of chilli.

Many thanks for your well written, interesting and well researched article. Nice to see something online where the pictures actually illustrate the content, too, instead of being mere decoration.

Thanks Katy. I think some of my best blogs are in my Travel series, but sadly, I don’t get as many readers as I do for my more controversial and political forestry stories.