In the early 20th century, Hervey Bay was not the bustling regional hub we know today. Instead, it was a picturesque cluster of seaside villages along the foreshore, stretching from Urangan in the east westwards to Torquay, Scarness, Pialba and finally Point Vernon. As tourism grew, particularly during the long summer holidays, safe swimming became a serious concern for both visitors and locals.

While modern retellings often focus on shark attacks, the original motivations for building swimming enclosures were broader. Safety from drowning, the creation of designated changing areas, and a push for modesty at the beach were equally significant driving forces. Newspapers from as early as 1899 discuss local debates about constructing floating enclosures in rivers to reduce frequent drowning fatalities.

The idea soon evolved: a well-built netted enclosure would serve three purposes – to protect swimmers from sharks and stingrays, to reduce drownings, and to provide a centralised, modest space for beachgoers to change, putting an end to:

The present indecent method of performing these duties in view of everybody.

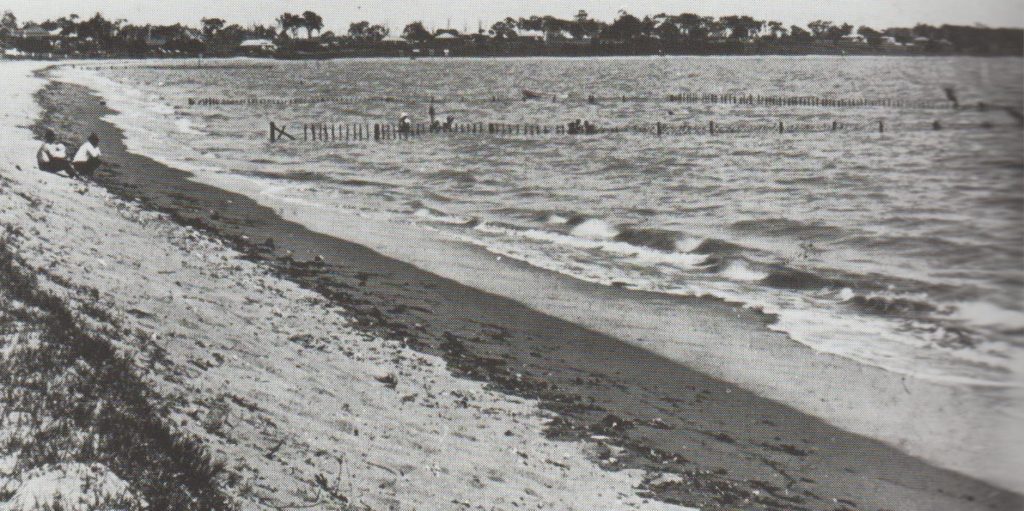

Hervey Bay once had several swimming enclosures along its coastline. These structures were essential to the region’s social and recreational fabric until their decline in the 1970s.

Safety first: the birth of swimming enclosures

Tragedy struck in December 1922 when 19-year-old Alfred Gassmann was fatally mauled by a nine-foot shark in shallow waters at Pialba. His right side was torn away from the armpit to the stomach, and he died after struggling onto the shore. It is Hervey Bay’s only known shark fatality, which shocked the community. Although isolated, the incident and repeated shark sightings spurred urgent discussions about creating safer swimming spaces. Around the same time, Australia’s first ocean swimming enclosure was constructed at Coogee Beach in Sydney, offering a model for Hervey Bay to emulate.

Early ad hoc attempts by hotel proprietors like Mr Hogan at the Hervey Bay Hotel to build small private enclosures were unsatisfactory for public use. However, by late 1923, residents at Pialba and Torquay mobilised to construct more substantial communal enclosures.

At Pialba, an official public swimming enclosure opened just before Christmas 1923, attracting over 400 excited attendees. Posts concreted into the seabed supported tea-tree pole walls bound with wire cables, offering bathers a relatively safe haven, at least during high tides.

The Pialba enclosure was a hub of activity located at the end of Main Street. It became a central feature of the growing township, complete with diving boards, although it was only functional during high tide.

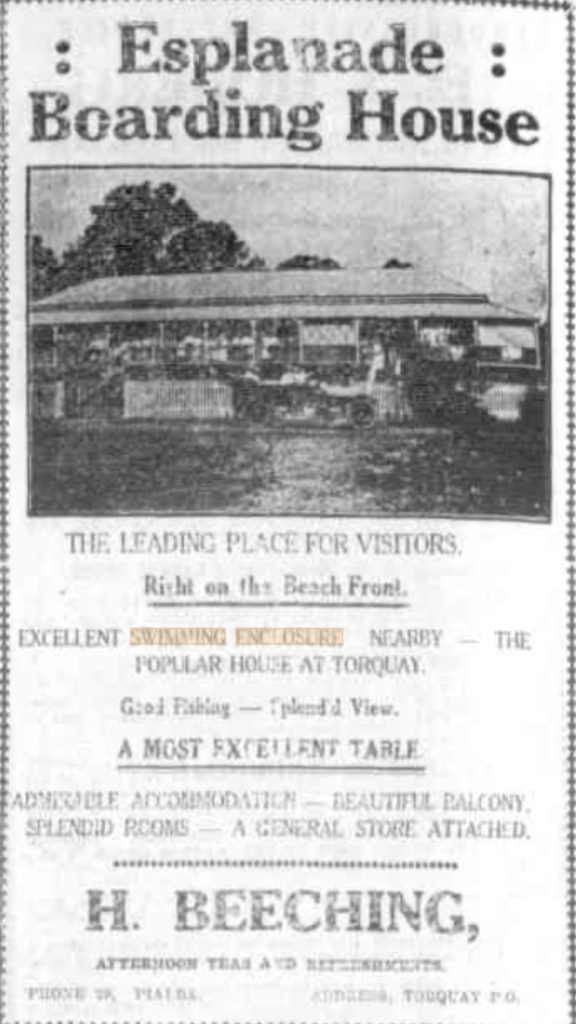

Similarly, Torquay soon boasted a swimming enclosure across from the Torquay Hotel, serving as a significant draw for the increasingly popular holiday destination. However, after two early failures in which enclosures were washed away, Torquay residents constructed a more permanent structure at what is now Bill Fraser Park.

Expanding the safety zones

By 1925, Hervey Bay had swimming enclosures at Pialba, Scarness and Torquay. Advertisements from boarding houses proudly listed “nearby swimming enclosures” as key selling points.

The initial, hastily built swimming enclosure at Scarness soon fell into disrepair. Not to be outdone, the residents pushed ahead for a better swimming enclosure during the mid-1920s. By 1927, the Scarness Sports Club, rallying local support, undertook a major fundraising campaign to rebuild the facility. Posts were driven into the sand and bound with galvanised wire to create a sturdier, safer enclosure. It became a point of pride for the community.

Meanwhile, a different type of swimming enclosure was taking shape at Point Vernon — one less reliant on timber and more integrated with the natural landscape. Around the late 1920s, Andrew Dunn, the influential owner of the Maryborough Chronicle and a prominent local figure, constructed an enclosure that cleverly utilised the existing rock formations. Additional rocks were moved to stabilise the area, and timber rails were installed to secure the swimming space. Dunn’s private boatshed overlooked the site, solidifying the enclosure as a unique blend of human design and nature’s architecture.

Although smaller and more rugged than its timber-and-wire cousins to the south, Dunn’s enclosure would prove to be the most enduring of all, with its skeletal remains still visible today at very low tides.

Talk of a swimming enclosure at Urangan began in 1927 as part of a broader plan to enhance Urangan and make it more appealing to visitors. An enclosure was constructed east of the Urangan Jetty at Dayman Point. Not much, however, is known about the establishment of this enclosure and its history.

Beach changing sheds

Hervey Bay’s unique beach bath houses, known as “beach change sheds,” have a rich history. These privately owned structures dotted the foreshore from Point Vernon to Urangan, allowing ladies to change before and after swimming. The sheds, numbering at least 60 between Point Vernon and Urangan, were a distinctive feature of the Hervey Bay foreshore and were a unique feature on Queensland’s beaches. They became a significant part of the social fabric of the community, with some sheds even including amenities like slides and lighting.

The tragedies that shaped the enclosures

The 1930s heralded a new wave of construction and improvements. In 1930, the Torquay Progress Association proudly unveiled a much larger and more permanent enclosure. Built with durable cypress pine posts and galvanised fencing wire, it featured a 90-metre beachfront span and an 80-metre extension into the sea. A four-foot-wide timber jetty graced its western flank, allowing swimmers easy access to deeper water without wading across tidal flats.

The local community was angry that the enclosure was built about 150 metres east of the Torquay Hotel! Nonetheless, the new site was much better than the previous one because it provided more sand to stabilise the posts and prevent the enclosure from washing away, as it had on two earlier occasions

The permanent Scarness enclosure, constructed in the late 1930s and connected to the dilapidated jetty, was the grandest of all enclosures. It featured diving platforms, slippery slides, and other attractions. A higher, broader, and more durable jetty was built opposite the infamous and iconic Scarborough Hotel (on the same site as the current Beach House Hotel).

But tragedy soon overshadowed the community’s optimism. On Christmas Day 1936, disaster struck at Scarness when two teenagers were fatally electrocuted while playing on the diving board of the enclosure early on Christmas morning. The enclosure had recently been fitted with electric lighting to allow for night swimming — a novel luxury at the time. However, dangerously close to the diving board, a poorly installed live wire transformed festive excitement into heartbreak. Overnight, a strong northerly had blown, causing one of the wires to hang dangerously low.

The seventeen-year-old stood to dive and swung his arms above his head. As he did so, his hands came into contact with the live wire. Clutching the wire, he was hurled forward, dragging the wire with him so that it struck the other boy across the nape of his neck. Both were electrocuted and fell into the sea.

While the elder boy’s body was rescued immediately, the other boy’s body was not found until 20 minutes later when it washed up onto the beach.

The incident rocked the region. Legal battles followed all the way to the High Court of Australia. The Burrum Shire Council was liable for damages, forcing them to impose a levy on ratepayers to cover the court-awarded costs and payouts to the two families affected. In the aftermath, public confidence in the enclosures wavered. Diving boards were removed, and debates flared about whether the entire concept of swimming enclosures was worth the risk, given that, ironically, more deaths had occurred within their fenced boundaries than from shark attacks themselves.

Shark tales and wartime mesh

Despite the tragedies, the community’s love for the seaside endured. In 1937, Australia introduced shark nets at some popular beaches, and Torquay was among the first in Hervey Bay to trial this innovation. However, maintaining the nets was a constant struggle, with reports of large sharks swimming nonchalantly along weakened barriers.

Not long after, the shark net was in poor repair, and two swimmers were in four feet of water when they sighted what is believed to be a 12-foot shark that was not attempting to get through the hole but was merely swimming slowly along the barrier.

Colourful shark encounters became almost legendary. In 1939, a visiting fisherman from Victoria proudly hauled a bizarre two-headed, 11-foot tiger shark from the waters near Torquay’s enclosure. The newspaper reported rather cheekily that the shark was the first of its kind:

Born with two heads owing to its father having swallowed a double-headed penny when the coin rolled over from a launch on which a two-up game was in progress.

On another occasion, a nine-foot shark was caught regurgitating a smaller grey nurse shark right onto the beach, much to the fascination (and horror) of the onlookers.

This was a popular pastime in the Bay, where fishermen proudly showcased their large catches for the curiosity of visitors and residents. As in the picture below, the sharks were often displayed at the Torquay foreshore, and they consistently generated considerable interest.

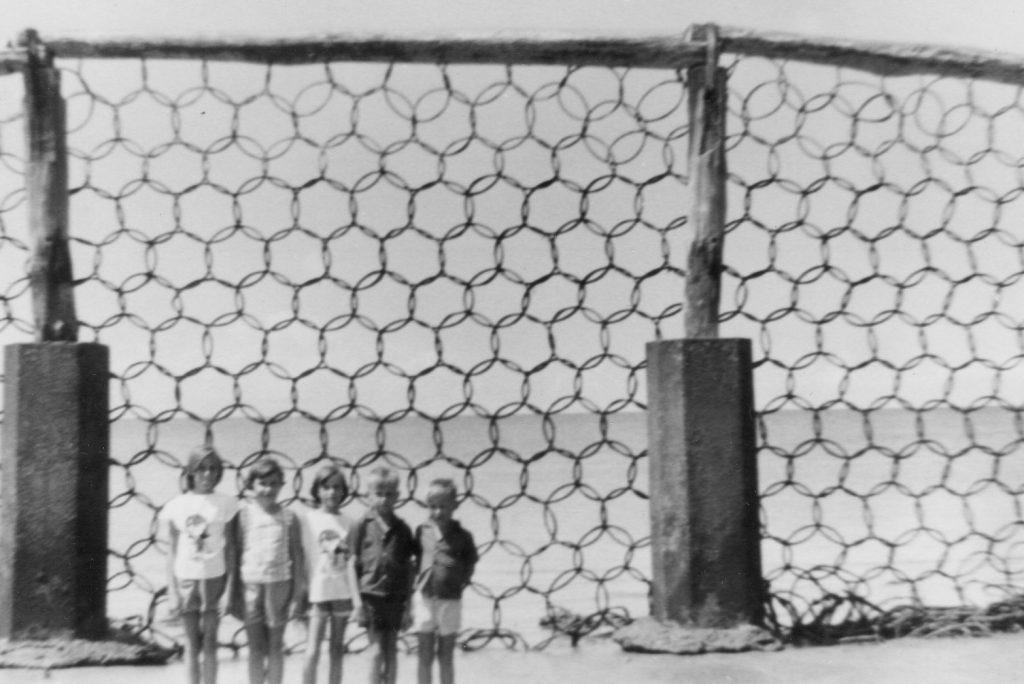

The Second World War brought unexpected upgrades. In 1952, the Scarness enclosure was reinforced with heavy-duty mesh salvaged from Sydney Harbour’s wartime defences—netting originally designed to keep Japanese submarines out of Port Jackson.

The gradual decline of the enclosures

The Scarness and Torquay enclosures were the best known, but nothing remains of them apart from the upgraded jetties, which signal the location of each. They boasted nets, diving towers, slippery slides, electric lights, and even public amenities at their peak. For decades, they were a hub for fun, family outings, and seaside picnics.

However, by the 1970s, time and tide had taken their toll. Shifting sands, storm damage, increasing maintenance costs and heightened public liability risks made the enclosures increasingly difficult to sustain. Changing public attitudes also played a role: improved swimming skills, enhanced lifesaving services, and a greater acceptance of open-water swimming led to a decline in interest in enclosures, resulting in the gradual dismantling of the structures.

Remnants of a bygone era

Today, only Point Vernon’s rock enclosure is visible, a quiet testament to a bygone era when protecting swimmers meant rallying the entire community.

Occasionally, ghostly remnants of the Pialba swimming enclosure appear in front of today’s Water Park, stirring memories for those who know where to look.

Local lore speaks of up to eight swimming enclosures across Hervey Bay, including a little-documented one at the end of Zephyr Street. However, little is known about that one and others beyond those covered in this story. Hard evidence of these has faded like footprints in the sand.

Some great reading here Robert.

Great story. Enjoyed it — big difference from then to now.

When I was a child visiting on holidays, I swam at the Scarness beach enclosure early 1970’s. I would of been about 10 years old. The poles were still in place even though the netting had perished over time. Every year we came here for holidays at my Aunty’s. One year after seeing the movie Jaws we came to visit. Dad and I walked the the front for a swim at high tide and to my horror there was no enclosure, only the jetty!

As a new resident of Hervey Bay, I really enjoyed reading of its beach history. I now have a new lens to look through when at the beach. Thank you.

Another interesting read thankyou Robert.

Very interesting.

I’ve lived in Hervey Bay since 1954 (except for a period from 1965 to 1971) and visited from Maryborough before that.

I remember swimming in the Urangan and Scarness enclosures in the 1959’s and 60’s.

As a teenager, it was a challenge to dive from the top rail of the Scarness jetty. Not a recommended activity, as I found out when diving into shallow water. Fortunately, I hit the sand with my outstretched hands and not my head. I was very cautious after that.

The photos are very interesting, particularly in the contrast between the beaches then and now.

These days, we don’t have the wide stretch of beach at high tide that there was prior to the marina being built.

Could you give me a better idea of where Dunn’s enclosure at Point Vernon was, or where I have walked it many times, but I’m not sure exactly where.

Thank you

Hi Brid, without being able to attach a map, I can describe it as being about 100 metres south of the boat ramp at the Gables (opposite Aplin St). If you look at Google Maps, you can see the outline of the rectangular shape from the rocks. Best viewed on-site at low tide.