The beginnings

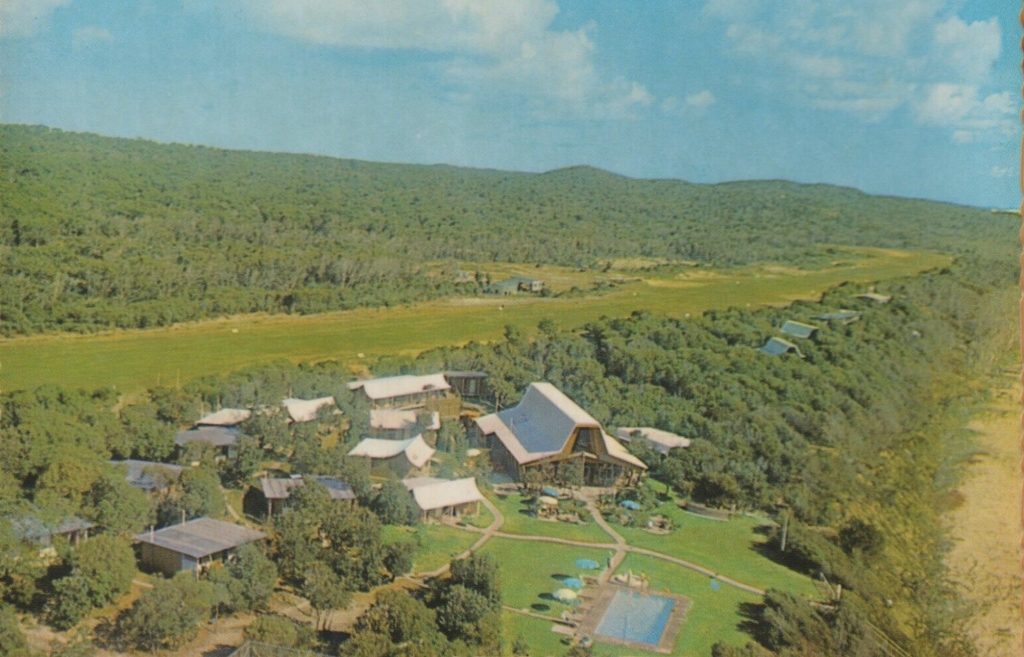

Sir Reginald (Reg) Barnewall’s ambitious dream of developing a resort on Fraser Island is a fascinating chapter in the island’s history. In the 1960s, Barnewall envisioned creating a high-end resort that would attract visitors to the island’s natural beauty, which was then known more for its timber industry and fishing than for tourism.

He chose the idyllic beach immediately north of Waddy Point on the northern side of Fraser Island as the site for his venture. This location offered stunning ocean views, and Barnewall named it Orchid Beach.

Although the area was a renowned fishing spot for local anglers, access was notoriously difficult. To address this issue, Barnewall built an airstrip to offer day tours and a basic A-frame angler’s lodge, flying visitors from an airport at Scarness Heights at Hervey Bay. Over time, accommodations, guest facilities, and infrastructure were added to support a luxury resort experience in this remote environment.

The resort’s design was particularly notable. It was inspired by traditional Samoan fales (or felts, as they were sometimes miswritten). Barnewall, having spent time in the South Pacific, was captivated by the simplicity and harmony of Samoan architecture, which blended seamlessly with the natural environment.

The fales are typically open-sided structures with thatched roofs supported by wooden posts, providing excellent ventilation and natural cooling while offering protection from the elements. Barnewall replicated this concept at Orchid Beach, tailoring it to Fraser Island’s conditions. The resort’s accommodations and communal spaces were designed with open-plan layouts, natural materials, and an emphasis on merging indoor and outdoor living—ideally suited to the tropical climate and the area’s natural beauty.

He sourced timber locally, particularly satinay and brush box, renowned for their weather resistance. Pandanus leaves were used for thatched roofs, mimicking the Samoan aesthetic. The result was a resort that offered guests a sense of escape and immersion in nature, aligning with modern eco-tourism principles long before they became popular.

Unfortunately, the resort’s innovative and environmentally sensitive design could not withstand nature’s destructive forces. Cyclone Dinah in 1967 posed a major challenge, but the breaking point came with Cyclone Ada in January 1970, which wreaked havoc on the resort. A year later, Cyclone Daisy compounded the damage. By 1974, a severe low-pressure system further eroded the area, leaving the swimming pool precariously hanging over the edge of the foredune. This once-prestigious feature became an ugly reminder of the destruction until it was finally removed in the early 1980s.

The cost of repairs, combined with the logistical challenges of rebuilding in such a remote location, proved insurmountable. Mounting opposition from environmental activists, even though Barnewall employed the main antagonist’s parents and siblings, added to his woes. The island became a political football as strict restrictions were imposed on the resort’s operation. By 1972, Barnewall decided to sell the property, marking the end of his dream.

While the resort’s legacy of blending architecture with the natural environment remains a fascinating footnote in Fraser Island’s history, no large-scale resort has been successfully developed there since.

A fishing expo is conceived

After the sale of Orchid Beach, the site’s ownership remained unclear for several years until a consortium led by Brisbane car dealer Keith Leach purchased it in 1983.

Leach had a bold vision to turn Fraser Island into a premier destination for recreational anglers. He recognised the island’s untapped potential as a prime fishing destination, with its abundant waters teeming with tailor, whiting, and bream set against a rugged and isolated backdrop.

Leach organised a fishing competition to celebrate the island’s incredible fishing opportunities, promote tourism, and emphasise sustainable angling practices. He aimed to create a community-focused event that would attract anglers from across Australia and eventually the world.

In a masterstroke, Leach decided to host an annual fishing contest in the quiet month of May to attract visitors to the declining resort. The inaugural Orchid Beach Fishing Expo, held in 1984, was a novelty designed to boost bar and dining revenue. More than 100 entrants from south-east Queensland chased $10,000 in prize money, comprising $2,000 for the biggest fish in each category plus $2,000 cash and an extra $2,000 worth of prizes. Strong winds and big seas prevailed for the first two days, but plenty of fish were caught. It quickly became a success, offering substantial cash prizes and attracting 800 participants by 1986.

Leach would invite journalists from motoring, fishing, and outdoor magazines to a long weekend in November at Orchid Beach for a preview and a story to help promote the upcoming fishing event the following May. The first official judge was Dave Bateman, and after five or six years, Gary Howard took over.

Things didn’t go well at the second event. Rain and strong south-easterly winds played havoc. Not only were the fish hard to come by, but the tent holding all the prizes blew down, breaking the weighing machine. Luckily, Leach organised for a replacement machine to be flown up from Brisbane in time for the improved weather conditions and successful catches.

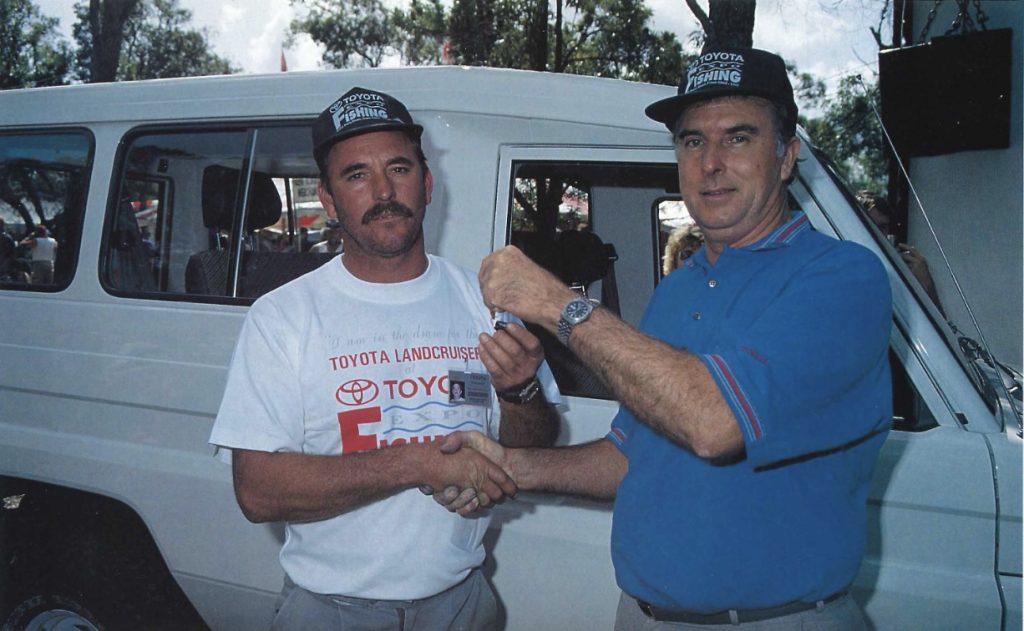

Toyota’s involvement in 1986 was a turning point. As the major sponsor, Toyota elevated the Expo to international prominence overnight, making it the southern hemisphere’s richest and most popular fishing event. Their support included significant prizes, such as a new Toyota 4WD vehicle—ideal for Fraser Island’s challenging sandy terrain—which became highly coveted among aspiring anglers.

A contestant at the 1987 Expo recalled a heated controversy that erupted on the final night. That year, the prize for the heaviest fish was $3,000, with an additional $1,500 awarded for the heaviest fish in each category.

His mates had done well—one was leading with a hefty starfish, while another held the top spot for the heaviest whiting. Confident in their wins, they checked with officials before leaving Happy Valley to collect their prizes.

However, just two hours before the cut-off, an angler presented a flathead and a whiting that overtook both categories. Rumours spread like wildfire—many suspected the fish weren’t caught during the Expo but had been netted elsewhere. Concerned competitors called in the on-site Fisheries officials to assess the situation.

Unfortunately, before any further scrutiny could take place, the new leader took his fish to the beach, promptly cleaning and filleting them. When he later collected his prizes, tensions boiled over. Furious at being labelled a cheat, he threw a few punches, sparking a brief scuffle.

In the aftermath, the Expo organisers were forced to tighten the rules. From that year forward, any fish deemed a category leader became the property of the event to prevent future disputes.

The rise of a global phenomenon

Under Leach’s leadership and Toyota’s sponsorship, the Fraser Island Fishing Expo grew rapidly, earning its reputation as one of the world’s largest and most prestigious recreational fishing competitions. Thousands of anglers flocked to the island annually, competing for prizes, enjoying camaraderie, and immersing themselves in its stunning environment. By 1987, the number of applications was capped at 1,500. Numbers were initially allowed to increase to 2,000, but this proved difficult to manage effectively, so they were reduced back to 1,500 shortly after.

Doug Bell, from Oz Hire, did a lot of background organising for the event, setting up the staging area, tents, weighing area, and prizes, and providing all the necessary equipment.

The Expo also became a major economic driver for the region, boosting local businesses and raising awareness about Fraser Island’s natural beauty. It pioneered sustainable fishing practices, including catch-and-release categories, which protected fish stocks and aligned with conservation efforts.

By the 1990s, the Toyota Fraser Island Fishing Expo had evolved into a cultural phenomenon. It attracted international attention and solidified Fraser Island’s place as a world-class fishing destination. The Expo was a marketing goldmine for Toyota, significantly driving sales of its 4WD vehicles in Queensland.

Unfortunately, controversy reigned during the 1990 Expo, when officials moved to ensure the competition’s reputation was upheld by exposing an attempt to cheat without disclosing the means. However, the event was still a success, and reports said it was the largest gathering of 4-wheel-drive vehicles for a single event anywhere in the world. Lindsay Negus cemented his skill at fishing, winning the tusk/parrot fish category with a 10.9-kilogram parrot fish, his fourth win in four years in that category. Competitors came as far as Thredbo to compete in what was now Australia’s premier beach and offshore fishing contest.

Officials from the Queensland Department of Primary Industries Boating and Fisheries Patrol were present at the 1991 event to provide boating safety services, operating a comprehensive marine radio service. They also verified that the fish caught were within legal size limits and that bag limits were adhered to. As an incentive for boaties to do the right thing, officers offered $500 prizes daily to those who displayed common sense and courtesy.

The Wednesday night of the event saw the weigh-in area transformed into a mini Lang Park as competitors and spectators supported their State of Origin team. Prizes on that night included the Maroons jersey.

Change of management and persistent opposition

The election of Wayne Goss’ Labor government in 1989 dramatically changed Fraser Island’s management. Following this, the 1990-91 Commission of Inquiry into the Conservation, Management and Use of Fraser Island and the Great Sandy Region, chaired by Tony Fitzgerald, played a pivotal role in reshaping the island’s future. The Goss Government initiated this inquiry in response to mounting pressure from environmental activists. It followed closely on the heels of the cessation of sand mining on the island in 1976 and increasing pressure from activists to end logging and prioritise preservation efforts.

The inquiry’s recommendations, released in May 1991, emphasised environmental preservation over wise resource use. These changes indirectly affected the Fishing Expo. The Orchid Beach airstrip was closed, the resort’s remnants demolished after the 1995 event, and the site restored to its “pristine” condition.

Leach was told he could only hold his annual fishing expo at Orchid Beach until 1995, following intense pressure from leading environmentalist John Sinclair and his group, the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO), on the Queensland National Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS).

In 1996, Leach approached the Hannants at Cathedral Beach to host the expo, but they rejected his proposal. Leach then approached Sid Melksham to host the event at Eurong Resort. The ideal location for the nightly weigh-ins, presentations, and entertainment was behind the main buildings. However, Sid was anxious that the foot traffic would damage his precious lawn, so he offered the industrial compound near the rubbish dump, about half a kilometre behind the resort.

Eurong had its advantages, such as less travel up the island and the option of fishing in the Great Sandy Strait if the exposed surf beach was unsuitable. While the location was okay for beach anglers, it wasn’t favoured by deep-sea anglers as they couldn’t launch their boat on the exposed beach. Nevertheless, when Eurong hosted the event in 1996, mixed feelings prevailed, and the number of participants declined. Boat owners preferred to launch on the lee side of Waddy Point instead of directly into the exposed surf near Eurong, with the only safe launching spot located 30 kilometres south at Hook Point. Then, they had to navigate the notorious Wide Bay bar, which had its own issues.

Meanwhile, Leach decided to step back and sold the fishing contest rights to Toyota before the 1997 event. Recognising the potential demise of the event, Toyota carried out lengthy negotiations with the government to allow the fishing expo to return to Orchid Beach, albeit with numerous additional environmental conditions to appease Sinclair.

Sinclair persistently disparaged participants and sponsors alike, describing the event as an:

Orgy of drinking and slaughter of fishing on an unsustainable basis.

In one of his media releases from 1994, he stated:

While some of the ocker males want to go the remotest part of Fraser Island to escape the publicity and attention while they are overindulging, World Heritage areas are not intended to provide remote refuges for orgies.

In his Moonbi newsletter, Sinclair wrote:

Toyota continues to be dedicated to sponsoring the orgy of drinking under the guise of the Fraser Island Fishing Expo and is apparently not concerned at the image of drinking and driving Toyotas.

He also claimed there was unacceptable environmental damage at Orchid Beach each year that the event was held and attempted to discredit sponsors by asserting:

It is unlikely that any reputable sponsor would want to be associated with such an environmentally unfriendly and socially ugly event in the future.

Sinclair sent numerous threatening letters to government ministers, Toyota executives and senior bureaucrats, trying to exert influence he never possessed. In response to his relentless negative campaigning and accusations, the fisherfolk humorously dubbed Orchid Beach “orgy beach.”

Despite overwhelming community support, strong environmental safeguards, and widespread goodwill, Sinclair’s relentless campaign against the Fraser Island Fishing Expo came across as little more than vindictive badgering. Unable to control an event that didn’t align with his narrow vision—and perhaps frustrated that he wasn’t in charge—Sinclair seemed determined to shut it down, regardless of the facts or the positive outcomes. His ongoing attacks said more about ego and control than genuine environmental concern.

In 1994, Sinclair arranged for an “independent” journalist to attend the Fishing Expo, presumably expecting a damning report. Instead, the journalist found no evidence to support Sinclair’s claims. Campers were respectful, vehicle behaviour was cautious, and there was no sign of environmental damage or reckless conduct. Even the nightly gatherings—attended by over 1,000 mostly male participants—were orderly and good-natured, with none of the so-called “orgy of male drinking” or environmental vandalism that Sinclair loudly claimed year after year. His persistent negative portrayal simply didn’t stack up against reality.

Traditionally, the event was always held at the end of the landing strip. Still, with the resort gone, Toyota established a new staging area west of the airstrip, where marquees and pavilions were erected.

Toyota was also committed to ensuring the event was run sustainably and had minimal environmental impact.

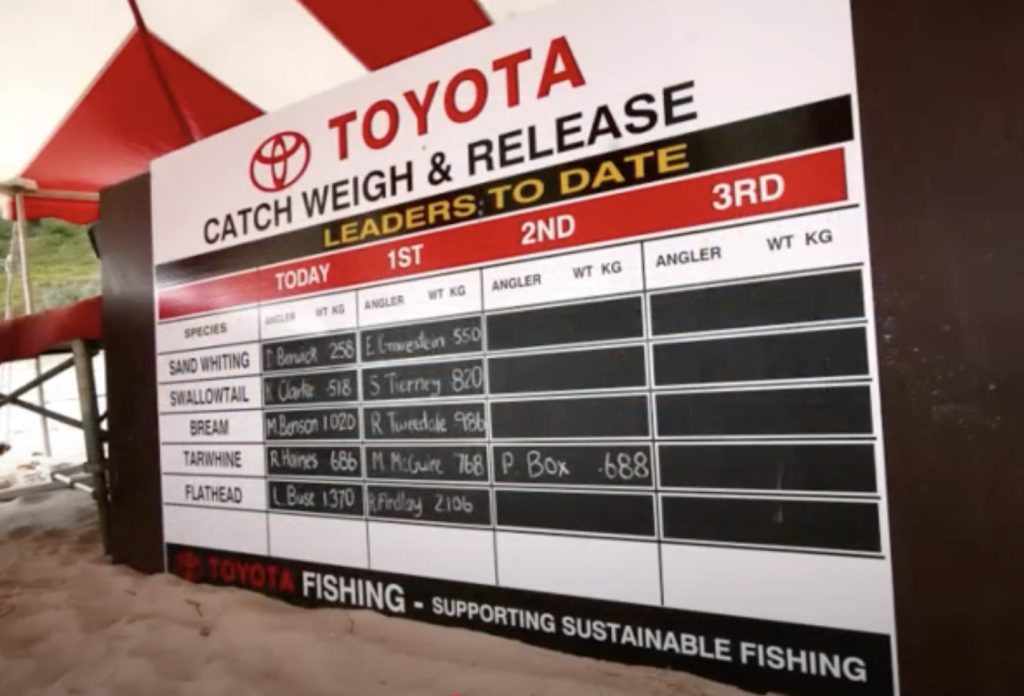

As part of the new stringent environmental conditions imposed on Toyota, extensive programs were initiated to educate anglers about preserving the island’s natural features for future generations. These initiatives complemented the tournament’s original and unique initiative—the “catch, weigh, and release” category, designed to minimise impacts on the fishing stock and assist government agencies in monitoring the growth of various fish species. After being caught and weighed, the fish were kept alive in holding tanks until the end of the day, when they were released.

This category only applied to surf fish such as whiting, tailor, bream, and flathead, not offshore fish. Gary Howard collaborated with Leech and his business partner, Gary McDonnell, to establish the concept. They carried out a few trials before introducing it to the competition to ensure its feasibility.

It proved to be highly successful in educating anglers on how to handle fish properly, both when keeping them alive and releasing them. Under the supervision of the Boating and Fisheries Patrol and marine biologists, they assessed what worked and what didn’t, including the fish’s reaction, among other factors. They even observed that some fish could dislodge the hooks by themselves, teaching anglers that they were better off cutting the line and leaving the hook in, especially if the fish had swallowed it, rather than trying to rip it out.

One popular scheme involved an annual cleanup during the Australia Day weekend to remove litter and attack weeds. More than 20 four-wheel-drive clubs participated, and in 2008 alone, volunteers removed more than 40 cubic metres of rubbish, 60 bags of noxious weeds and over 3,000 harmful plants.

Competitors were also urged to adopt “minimal impact camping,” which emphasised recycling, waste reduction, and installing an environmentally friendly sewage treatment plant that used an aerobic sand filter, providing natural treatment without chemicals. Additionally, a “ban the bag” scheme aimed at eliminating harmful plastic bags from the island.

Various initiatives such as “bin the butts” and “pick up your ring tops” highlighted the environmental programs flowing from the annual Toyota Fraser Island Fishing Expo. Portable ashtrays were included in competitors’ start-up packs for use while fishing. Another environmental initiative involved using an offal machine to mince fish waste, which was then released one kilometre to sea. Another involved cordoning traffic from tern roosting areas.

The anglers fully embraced the ideas, and during the camping competition, QPWS noticed that some campers had left their sites in better condition than they had found them. Lots of children attended with their parents, and they were well catered for. They were taught various bush skills and safety lessons from Surf Life Saving and the paramedics who were present, making it a valuable learning experience for them.

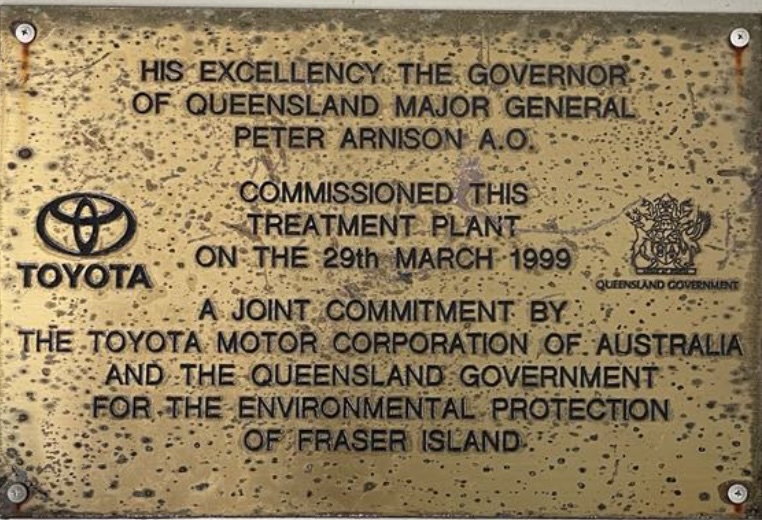

Toyota also funded the construction of a modern septic system at the expo site in 1999, which was opened by the governor of Queensland. It is still there unused, just filled with fresh water.

But of course, this didn’t stop Sinclair from hurling accusations without proof and writing a barrage of letters to QPWS and government ministers. He continued his tirade in his Moonbi newsletter, referring to the fishermen as “yobbos” and accusing them of engaging in degenerate behaviour.

However, the reality differed significantly from Sinclair’s obsessive and spiteful denigration of the event. As Gary Howard shared:

There are not too many sports that pull together a wide diversity of people, such as doctors fishing next to labourers. They are all equals regardless of their profession.

Reg Barnewall summarised the environmental success of the event each year when he wrote in his book:

Toyota takes away from Orchid Beach nothing but photographs and memories; they leave behind them only the wheel marks in the sand – soon to be erased forever by wind and tide.

A mini revival

Despite Sinclair’s relentless campaign against them, the fisher folk embraced these environmental initiatives, resulting in renewed interest as the event returned to Orchid Beach. In 2007, over 700 fish were released as part of the “Catch, Weigh and Release” category. Prizes worth more than $200,000 were available, highlighting the strong interest from sponsors. Lucky winners drove away with incredible prizes, including a Hilux V6 Manual SR, Yaris 3-door hatch and Haines Hunter 470 Breeze equipped boat with a Yamaha 80 hp outboard motor.

That year, nightly entertainment featured Tania Kernaghan, and the off-road Toyota evaluation drive track proved extremely popular with more than 300 test drives in Hilux, Landcruiser 70 and 100 series, Rav 4 and Prado vehicles.

To Sinclair’s dismay, the Queensland government revelled in the success of this world-renowned event. Unfortunately, all good things eventually come to an end, and such was the fate of the Fraser Island Fishing Expo, which held its last event in 2009.

The end

Just before the 2009 Fishing Expo, Toyota announced it would no longer renew its right to host the event. This marked the end of 26 years of the expo and Toyota’s long-standing involvement, including an 11-year period as the rights holder.

Despite the criticism and hostility directed at the event by environmental activists, nothing embodied the community spirit it promoted more than the funds raised at the last expo for Just4Kids, a charity focussed on teaching life skills to young kids in rural and remote Queensland – something Sinclair did not seem to value, as he consistently launched negative attacks against the event.

Leach’s vision, combined with Toyota’s strategic involvement, transformed a simple fishing competition into a global celebration of angling and adventure.

Beyond its community contributions, the Expo was a powerful marketing tool for Fraser Island. It showcased the island’s unique beauty and bolstered its premier fishing and 4WD destination status. Thousands of visitors left with lasting memories, reinforcing Fraser Island’s global reputation as a must-visit location for recreational anglers.

The end of the Expo also marked the conclusion of an era where large-scale events played a central role in Fraser Island’s tourism narrative. While anglers continue to fish on Fraser Island, the Expo’s legacy is a testament to the impact of visionary leadership and strategic partnerships in shaping regional tourism.

Even though the Expo is gone, its influence endures in Fraser Island’s identity. The island remains a cherished destination for those who experienced the camaraderie, excitement, and natural wonder that defined the Toyota Fraser Island Fishing Expo for over two decades.

Its legacy is long-lasting, as there has been nothing like it in Australia before or since.

What a great article. (46 year FRASER veteran)

Fair analysis of an event that was to leave lasting memories on my life. I was lucky to bring my sons, brothers, nephew, mates, and finally my grandson for the last two years to fish in this competition. All up, our group would account for approximately 90 to 100 members over 22 years from 88/09. Thanks for the memories.

I went to 23 of those fishing competitions and had a ball, meeting some wonderful people from all over the place. I never saw any evidence of what Sinclair was on about. It’s a shame it finished in 2009. We all used to look forward to those 10 days or so on the island.

Well researched Robert.

You lifted a scab. A Sinclair scab.

These gurus gather a mob of hand-out do-nothings and pester a marshmallow pollie cohort. Ditto Keto with the forest industry. Ditto Bowen with the coal industry.

A great story Robert, thankyou.