The Bass Strait submarine cables

In 1859, the first underwater telegraph cable in the Southern Hemisphere and the longest in the world was laid across Bass Strait.

Planning began in 1853 when discussions were held to build an overland line from Hobart in the south to Launceston in the north of Tasmania, extending across Bass Strait to Victoria.

The landline ended at Low Head instead of Launceston to accommodate the planned underwater connection. Initially, estimates were provided for a cable from Cape Grim, in the far north-west tip of the island, across Bass Strait via King Island to Cape Otway at £100 per mile. It was believed then that this route would provide a sandy bottom, reducing the risk of damage. A previous alternative, passing through the Furneaux Islands, was rejected due to rocky sections that risked cable breakage.

Launceston businessman Alexander McNaughton led the effort to connect Tasmania to Victoria. In February 1859, an agreement was signed to lay a cable from Low Head via Cape Grim to King Island and then onto Cape Otway. The cable ships Victoria and Romeo laid the underwater sections, completing the work six months later.

Despite its initial success, the cable failed within two years due to breaks in the line at a rocky section in Victoria Cove, King Island. While there were attempts to repair the damage, the outside covering of the wire was too defective. Also, the section between Low Head and Circular Head (Stanley), along the northern coast, was very shallow and prone to damage from the ship’s anchors. Repairs proved futile, and the cable was abandoned in January 1861.

This was a significant setback for the Tasmanian government and their plans to communicate with the broader world. Parliament resolved that the government, in conjunction with their Victorian counterparts, would “transfer the submarine telegraph to any person or company on the guarantee of it being kept in working order”. Nothing prevailed, and three years later, a Select Committee was formed to enquire about the best way to restore the submarine cable. It led to an agreement between the Tasmanian and Victorian Governments with the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company (TCMC) directors in 1867 to lay a cable for £70,000 in return for an annual subsidy of £1,200 from the two governments until the profits exceeded 100 per cent.

A new cable was laid directly between Low Head and Flinders, Western Port and completed in April 1869 using the TCMC cable ship Investigator, the Navy survey ship Pharos as tender, and the tug Tamar from Launceston Marine Board. Even though there were several breakdowns of the cable where it passed over a rocky reef at the Victorian end, they were located and quickly repaired.

The Hobart Mercury provided details of the installation project:

The 200 miles of cable, including 12 miles of heavy duty for the shore ends, was stowed on the Investigator in a tank 31 feet long, 22 feet wide and 12 feet deep, and fed out of the stern of the vessel over a seven-foot drum, with a braking apparatus to prevent the cable from running out too quickly, which could have caused the line to tangle or kink. The total weight of the cable was 498 tons. The shore ends weighed approximately 8½ tons per mile, and the deep sea section only two tons, one quarter and 19 pounds each mile. Both these sections were considerably heavier than the failed 1859 cable.

The submarine cable proved a great success. The TCMC made handsome profits, and the subsidy was terminated by 1882.

Further cables were laid in subsequent years. In 1885, a duplicate cable was laid between Flinders and Low Head six miles east of the 1869 route. In 1898, a new cable replaced the 1869 cable.

In 1902, the new Federal Government tried to purchase the cables, but no agreement was reached. Instead, it decided to install two new cables owned by the Postmaster General’s Office. These cables ran directly from Flinders to Low Head, known as the east and west lines. A year later, the earlier cables were recovered from the seabed.

In 1936, a sixth cable was laid specifically for use as a telephone line, as there were no phone connections from Tasmania to the mainland. The cable went from Apollo Bay to Stanley via King Island. It was a big occasion for Tasmania, as it no longer had to communicate with other countries by letter or telegram.

The modern and trouble-free radio link replaced the telegraph cables, and they quickly became obsolete. All the cables, including the telephone line, were removed by 1967, ending a colourful and interesting chapter in Tasmania’s communications with the rest of the world.

Jonno, the deep-sea diver

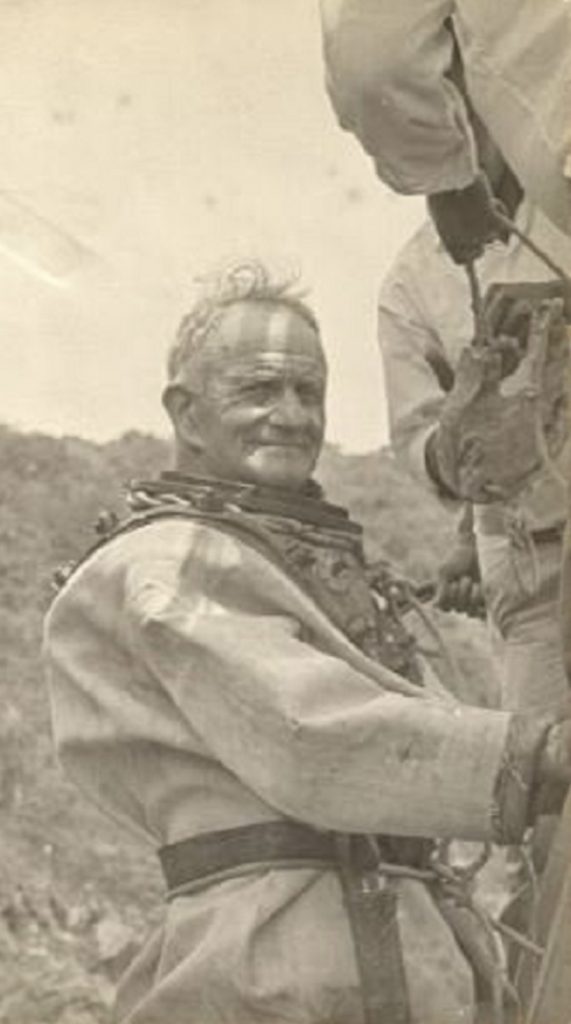

John “Johnno” Edward Johnstone’s life was an extraordinary blend of skill, courage and innovation. They include being trapped under a sunken ship, held prisoner by a groper, salvaging ships with Japanese bombers overhead, and retrieving half a million pounds in gold bullion from a wreck sunk off the coast of New Zealand.

Born in Liverpool, England, Johnno wanted to be a sailor in his youth, but his mother wouldn’t let him. After failed office jobs, he apprenticed as a shipwright in a ship repair yard at the Birkenhead. He signed as a carpenter’s mate aboard a cargo steamer destined for Australia, arriving in New South Wales in 1911 as a broke nineteen-year-old.

Johnno completed his apprenticeship in a shipyard at Coopernook on the Manning River near Taree (after walking from Sydney after missing his train!) before returning to England to enlist in the 17th King’s Liverpool Regiment in 1915. When volunteers were called to train as divers, he did so immediately.

After being discharged from the army to assist the war effort as a shipwright at Portsmouth Shipyards, he became a Diver’s Assistant. He was sent to Invergordon in northeast Scotland to start a formal deep-sea diving course. Although Johnno’s instructor wrote that his prospects as a diver were not good after his training, Johnno was introduced to the American invention of the underwater gas blowtorch. He mastered the device and became a skilled operator, patching holes in torpedoed British ships and working off the Orkney Islands.

After World War I, Jonno returned to Australia with his wife and baby daughter. They had twins in 1922, but sadly, his wife died two weeks later. His wife’s best friend became a carer for the children and later married Johnno.

Meanwhile, Johnno built his career as an adventurous deep-sea diver, advertising his services as a freelance diver. He worked for Lloyds of London salvaging copper from the cargo steamer SS Katarine in the Bass Strait. He also pioneered underwater diving techniques during projects like the Eildon Weir reconstruction, cutting girders at 122 feet, the greatest depth at which a blowtorch had been used.

In 1932, the SS Casino sank with the loss of 10 lives at Apollo Bay in Victoria. As he had done much repair work on this ship, Johnno was called to inspect the cause of the sinking and found that the ship holed itself on its anchor in a large swell. Johnno removed the brass propeller using 28 specialised hacksaw blades. He donated the propeller to the Port Fairy Community, and today, it is part of a monument in Port Fairy to commemorate the lives lost.

In 1938, the French Government engaged him to demolish the wreck of the Julette at Thio, 180 miles from Noumea. Using explosives and underwater cutting gear, he removed the wreck within 12 months and raised her cargo of 3,000 tons of nickel and cobalt ore.

Walking the Bass Strait

One of Johnno’s most famous feats was walking 43 kilometres along the Bass Strait seabed to find and fix a damaged section of the submarine cable between Tasmania and Victoria.

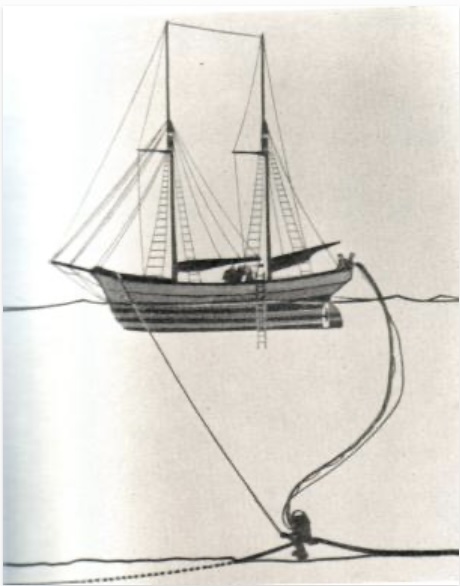

In 1938, amidst the looming threat of global war, Johnno was asked to locate a fault in the submerged telephone cable in the Bass Strait, the only communications link Tasmania had with the mainland. The cable had deteriorated due to large swells on the sea floor. He called on old friend Harry Burgess, skipper of the crayfish boat Julie Burgess to assist as his mothership. An engineer installed a phone system that ran cables from Johnno’s helmet back to the boat to provide real-time communication.

They sailed to Naracoopa on King Island, roughly halfway between Tasmania and Victoria. The engineer in charge of the booster power station on the island told Johnno that the cable had a fault somewhere between the island and Victoria. Johnno was shown where the cable entered the water, but nothing was said about its location below the ocean.

Johnno had to improvise to find the cable and the damaged section. They dragged a large hook over the sea bottom while the boat moved at a slow speed back and forth where they hoped the cable was lying. Fortunately, they picked it up relatively quickly. Johnno climbed down the grapnel rope to ensure they snagged the telephone cable, which, according to the engineer, was a copper wire completely covered in gutta-percha rubber solution and wrapped in waterproofing material.

Johnno recognised it immediately and lifted the cable about 20 feet above the seabed. The water was surpassingly very clear. He sat on the hook, hanging on tightly, for the tide was very strong, and surveyed the cable as it disappeared towards the bottom in two directions, then returned to the boat to discuss the best way to find the fault.

They sent down a large pulley block and fitted it under the cable. A wire rope from the pulley was attached to the boat. Johnno returned underwater, tied himself to the block, or held onto the wire rope. The Julie Burgess towed him along as it travelled ahead, and Johnno examined the cable while the pulley rolled under it.

This method worked well in fine, calm weather, but it was uncomfortable when the boat rose and fell due to a swell. Johnno was lifted and dropped as much as six to eight feet; the rope jerking nearly pulled his arms off. Occasionally, he had to let go and frantically swim back to the hook against a strong tide.

Johnno walked at a depth of 70 to 100 feet under the Bass Strait for six weeks, starting in September 1939. A replica deep-sea diving suit worn by Johnno is displayed at the Bass Strait Maritime Centre in Devonport. Johnno took Australia’s first underwater photographs during the work, further solidifying his reputation as a trailblazer in maritime engineering.

Johnno was warned about sharks and large octopi but never encountered any. He spent so much time underwater that he befriended a family of locals. On one shift, he was joined by three seals—his parents and their pup, who adopted him. Each day Johnno descended, they waited to welcome him, fascinated by this helmeted stranger in their waters. At the end of each day, they accompanied him to the surface, waiting until the crew flung them fish. One day, only the pup appeared, and the parents never returned. Johnno named his new friend Percy, and they had a great time together, including moments when Johnno stopped to decompress on his way up, and Percy would come close enough to have his nose tickled.

Then suddenly, Percy failed to appear. Later, while strolling along a beach on the island, Johnno found the body of a young seal washed up at the water’s edge. It had a deep gash in its side, and half its head was gone. Johnno wasn’t sure if it was Percy, but he thought it looked like his playmate.

Johnno’s career

Johnno’s fame grew after the Bass Strait project. He quickly became renowned for his skill and innovation. He contributed significantly to marine salvage operations, and perhaps his most ground-breaking and dangerous dives followed.

Some argue Johnno’s Bass Strait feat was overshadowed by his work during World War II. In June 1940, the passenger liner Niagara struck a German mine and sank in 134 metres of water off New Zealand. It had been on a regular run between Sydney, Aukland and North America. No lives were lost, but it carried 555 gold ingots from South Africa to pay for the British war effort.

Later that year, Johnno helped salvage £2.7 million worth of gold ingots. As the Niagara lay some 50 fathoms, regular diving suits could not be used. For the salvage, an enclosed chamber was designed and built at the Thompson Foundry in Castlemaine, Victoria. Today, the ‘Bell’ is on show in the Castlemaine Museum.

He travelled to Darwin in the Northern Territory and was working on American ships in Darwin Harbour on 19th February 1942 when the Japanese bombed Darwin. He was pulled out of the water, hid under a wharf and watched the bombs dropping.

In May 1942, Johnno and a couple of associates established the Commonwealth Salvage Board. Johnno was the chief diver and shipwright surveyor. They worked with the Australian Navy on wrecks in Darwin and Melville Island.

The following year, Johnno, accompanied by his young son Jack, refloated the Bantam, a Dutch vessel sunk by Japanese bombing in Oro Bay, New Guinea. He worked from an ammunition barge amid constant threat from enemy bombers overhead.

In 1943-4, Johnno assisted in raising the two Japanese Mini Submarines that had blown themselves up in Sydney Harbour. These submarines are on show at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

After World War II, Johnno salvaged Japanese wrecks around New Guinea and the Solomon Islands while working for a Japanese company. In 1953, he again worked on the Niagara and assisted a British salvage firm retrieve another 30 bars of gold. During this time, the Iron Man Suit was used.

Johnno took his last dive at age 73. After retiring, he moved to Frankston, on the outskirts of Melbourne. In his retirement, he restored and made furniture, did fine French polishing work, and was a perfectionist in every aspect of his work.

In 1968, Johnno was appointed a Member of the Civil Division of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) and passed away in October 1976, leaving a legacy of innovation and adventure in maritime history.

His indomitable spirit, unconventional approach, and relentless drive ensured his name would endure in the annals of diving history. Despite the immense endurance and fitness required for deep-sea diving, Jonno was a chain smoker of cigarettes and cigars—a fascinating dichotomy that added to his mystique. He wasn’t just a remarkable character; he was the man who walked the Bass Strait and a pioneer who transformed challenges into achievements, leaving behind tales that continue to inspire and captivate.

That’s awesome. I enjoyed this story, thanks.

A very interesting story about a very, very interesting person!

Great article Robert, Johnno achieved a great amount in dangerous conditions throughout his great diving career,

Great tale, a bit of history worth remembering. Thanks Robert

What a wonderful story about an amazing man. It should be made into a movie. Thank you for sharing this remarkable piece of history.

A great story, a true legend till this day.

Thanks for the article.

A real Australian pioneer. I can’t believe I haven’t heard these stories before.

Thank you Rob.

That was a great read, and kudos to his courage.

Really good read, thanks Rob!

Well done. A fascinating piece.