Gorse was brought to Tasmania in the early 1800s. Its principal use was as an ornamental hedge by settlers hoping to replicate the paddocks of England. The Reverend Knopwood purchased some English gorse at New Town, near Hobart in 1815. Writer, Louisa Anne Meredith, noted the widespread use of gorse for hedges on the east coast by 1841. Her friend, William Howitt, wrote some years later in 1854:

“Splendid hedges of English furze [gorse] enclosed the approach to Mr Charles Meredith’s house, in blossom even at this winter season and diffusing in the sun its familiar odour“.

Its use was not confined to the east coast. Farmers in the Midlands planted it widely in their paddocks. However, the qualities that made it attractive as a hedgerow plant were also those that, in the long run, made it a big problem in the landscape. Louis Meredith wrote critically of her father-in-law who had:

“…cleared the land of trees and planted miles and miles of gorse hedges, which became a very costly curse and ruined much good land“.

The were reports of gorse in the Chudleigh area in 1883. By 1895, the gorse problem was quickly becoming “notorious in this island”. A Campbelltown resident blamed the gross negligence on farmers and “land monopolists” for allowing it to spread over good farming land.

The origin of the gorse that covers the Hampshire Hills estate and surrounding areas was at the homestead site built in the late 1820s by the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.).

The VDL Co. employed Henry Hellyer as an architect and chief surveyor. His first task was to locate agricultural land in the north-west of the state – country that was densely forested, mountainous and unknown. He saw some distant open country near St Valentines Peak when he climbed peaks on the upper reaches of the Mersey River. After a month-long expedition in the summer of early 1827, the VDL Co. selected more than 200,000 acres in adjoining blocks named Surrey Hills, Hampshire Hills and Emu Bay.

Edward Curr, the VDL Co’s first Chief Agent, decided to build a settlement at Hampshire Hills. The Hampshire Hills homestead site was the headquarters for pastoral activities in the Hampshire and Surrey Hills estates. It is the first inland European settlement in north-west Tasmania.

Hellyer supervised clearing the road to Surrey Hills from Emu Bay with a gang of about five men. The road was little more than a muddy track tunnelling twenty miles through dense forest to the Hampshire Hills. Curr inspected the road at the end of September 1827 as part of his visit to Surrey and Hampshire Hills.

(Left) Edward Curr

The original purpose of the Hampshire Hills site was to shelter and secure loads from Emu Bay to Surrey Hills with a yard for yoking the bullocks and enclosing the buildings and a hut for the drivers.

The site didn’t operate for long as the idea of rearing Merino sheep for wool failed spectacularly. However, the VDL Co. built several buildings before its demise, including a Superintendents cottage and garden, a store and office and nine cottages, carpenters and blacksmiths shops, a barn, two stall stables, cattle and calf sheds, pig styes, stockyards and ram sheds. Also, there were 545 chains or 67/8 miles of fencing. They also planted a hawthorn hedge, gorse and many fruit trees. In January 1829, Lieutenant Governor George Arthur visited the site and wrote that the “station presented a beautiful rural scene reminiscent of a substantial English farm”.

The VDL Co. ran some cattle and hardier breeds of sheep after their initial failure. But by the 1850s, they had virtually abandoned the property. The Field brothers leased Hampshire and Surrey Hills from 1858 running cattle herds.

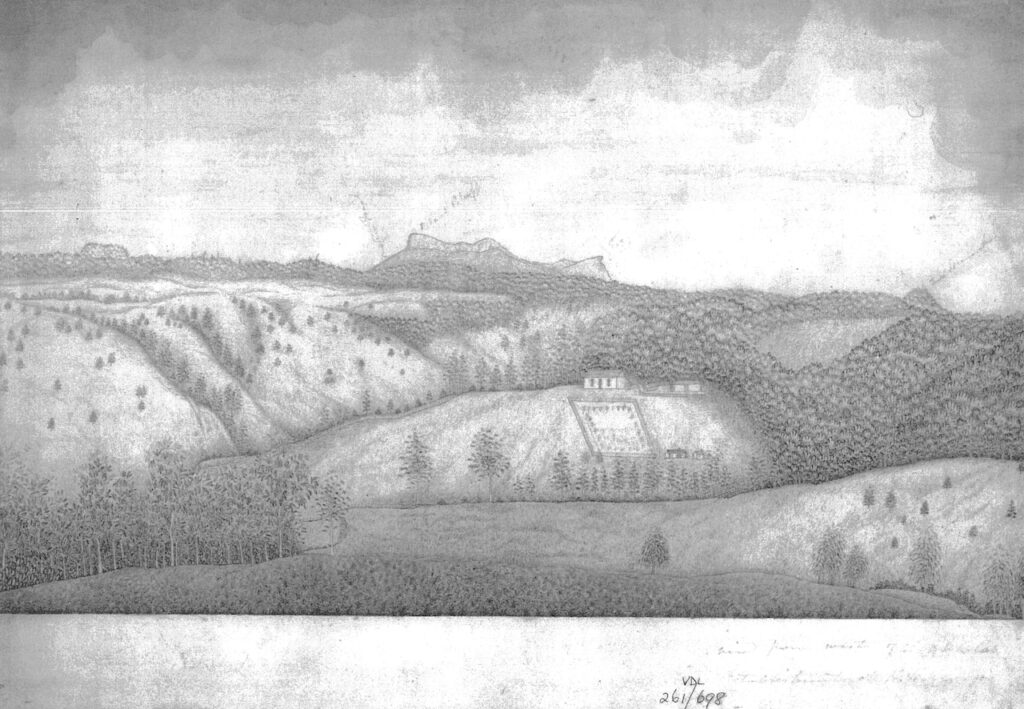

(Right) Drawing of Hampshire Hills, looking east, by Dr John Hicks Hutchinson in 1830. Copy gratefully supplied by Brian Rollins. TAHO VDL 343/261/698.

By the end of the 1860s, the VDL Co’s old stations were in a state of dilapidation. However, one of the Fields’ stockmen, Harry Shaw and his wife Bridgett and a cook lived at Hampshire Hills.

Richard Hilder passed the area in 1873, saw the abandoned settlement, and noted, “English gorse, hawthorns and a few Kentish cherry trees grew luxuriantly”. Another visitor to the Hampshire homestead site recorded seeing:

“…a deserted station which possessed a melancholy interest with its ruined huts, its splendid hawthorn, hazel and elm rows and its multitude of apple, cherry and peach trees all in blossom”.

It was a rather flattering description for a site that revealed an exuberant and rank growth of fruit trees, gorse and wild briar.

The first reference to gorse in the Hampshire Hills, Upper Natone area, after abandonment by the VDL Co., was a newspaper report in 1864. Gorse was promoted as winter food for dairy cattle. One farmer didn’t have to rely on hay while using gorse, while another argued that 31/2 bushels of crushed gorse with some hay and swedes were a good nutritional feed for a cow each day.

Gorse was reported as making “splendid fences” as it “thrives well and grows fast and makes a good protection for cattle against the wind”.

(Left) Richard Hilder.

But by 1895, gorse was seen as a problem. The local Road Trust called for tenders to grub the gorse on the Burnie to Waratah Road.

Then, in 1909, Andrew McGaw, the Chief Agent of the VDL Co., wrote to London that the gorse at Hampshire had spread to nearly one-half of the estate and would need to be grubbed at a very high cost.

At its meeting in March 1921, the Emu Bay Council recognised the spread of yellow gorse and decided to proclaim it as a noxious weed. Table Cape Council did the same in October 1923. This pleased a local Hampshire resident who claimed that over 1,000 acres of the best land at Hampshire was covered in gorse. He wrote that gorse was spreading at a “rate of hundreds of acres every year”, threatening to crowd out the settlers.

An Australian entomologist in New Zealand, Robert Tillyard, claimed in 1927 to have a biological remedy to control the spread of gorse. Because gorse was recognised as a valuable nitrogen fixer and a fodder crop for sheep, his work focussed on finding an insect that would control the prodigious seeding ability of gorse by eating or destroying its seeds but not eradicate the plant.

(Right) Robert Tillyard

However, it wasn’t until more than a decade later that the gorse seed weevil was released in Tasmania after first being released in New Zealand. Unfortunately, its impact was limited because larvae fed only on seeds during spring and early summer but not during the second period of seed production during autumn and winter.

By 1936, the sight of gorse in flower in the Hampshire/Upper Natone area was considered a tourist attraction. On his visit to the district, Mr Gawlor was “impressed with the sight of hundreds of acres of the most wonderful display of gorse flowers he had ever seen”. He thought it worthy of bringing to the attention of tourists in the area. Another visitor to the grave sites at Hampshire Hills remarked, “they are simply mounds, covered with gorse, the wooden crosses having long ago perished”.

At the same time gorse looked splendid in all its flowering glory, politicians were debating the introduction of a Noxious Weeds bill in an attempt to arrest the spread of many weed species, including gorse.

Even when forestry activities began in the Hampshire area, particularly the establishment of plantations from the 1970s, gorse posed a significant problem. While the machinery associated with the plantation operations helped spread the gorse, its impact was already present.

(Left) Gorse in plantation area at Hampshire Hills.

Today, gorse is a significant and widespread infestation at Hampshire Hills. The only way to deal with the problem is to contain its spread and rely on biological control to dampen its prodigious seed production.

In 1998, the gorse spider mite was released. It forms colonies on the plant by spinning a tent-like white web, feeding and web spinning as it moves around the gorse. The colonies feed on the leaves of mature gorse plants. Unfortunately, while the spider was widely established in Tasmania by the spring of 2001, its impact was affected by other mites and insects which fed on it and destroyed entire colonies.

The gorse thrip was first released in 2001, and while it was successfully established, its spread was very slow, hardly impacting the gorse. So entomologists reared another thrip of Portuguese origin for release, hoping it would spread faster.

(Right) Spider mite colonies. Photo Peter Martin.

The gorse soft shoot moth was first released in Tasmania in the spring of 2007, including at Hampshire and Guildford. Early results were not great as the moth was not found at nearly 50 per cent of the release sites. It is now believed that the soft moth is unlikely to establish in the inland regions of north-west Tasmania, such as Hampshire, where the mean annual rainfall is above 1,500 millimetres per year.

In the past, Gunns carried out some gorse control work, mainly focused on mapping infestations and eradicating outlier areas. However, funds were limited, and the program was sporadic and uncoordinated. They successfully received a $25,000 grant through the Cradle Coast Authority about 12 years ago for much-needed work in the worst areas around the Fingerpost and to attack various outlier infestations.

In recent times there has been a more concerted and active program implemented by Forico to contain the spread of gorse and broom at its worst locations and eradicating outlier infestations. Forico favour mulching, burning and regular follow-up weed control in some of the more heavily infested outlier areas. Burning promotes seed emergence and makes it easier for follow up weed control activities.

Areas that have been targeted include Muddy Creek, near Guildford, and the Fingerpost on both sides of the highway on Surrey Hills; Sugarloaf, between Kingsclere and the Natone turnoff and areas near the woodchip mill, both on Hampshire Hills. The Sugarloaf area had been mulched several times in the past 30 years but was allowed to regrow without any follow-up work. Forico more recently mulched the site in 2016 and have continued to conduct regular follow up weed control since. All sites show signs of a successful and persistent recovery program to a more natural environment as long as follow-up monitoring is maintained.

Photos Adam Crook.

Machinery used in plantation harvesting and site establishment operations in the broader Hampshire/Upper Natone core infestation area must be thoroughly cleaned and inspected before leaving the site to prevent the spread of gorse. To minimise the risk of gorse spreading, Forico has a program of keeping the same contractors working in the core infestation areas, rather than a machine leaving for another job and a different machine accessing the site.

Under the State government’s Weed Action Fund (WAF), Forico has partnered with Cradle Coast Authority, State Roads, TasNetworks, TasRail, Crown Lands and private landholders and identified the corridor along the Ridgley Highway between Highclere and the Fingerpost as a significant weed infestation area. Under the stewardship of the Burnie City Council, a considerable amount of funding has been provided over three years by the WAF for a joint program of mulching, burning and spraying to get on top of the weed problem. Under the agreement, all participants are required to spend the same amount as the grant money each year.

While gorse was seen as a nice ornamental plant and farmers thought it was beneficial for their properties, it became obvious the aggressive weed simply took over areas where it was allowed to proliferate. While it is now nigh on impossible to eradicate it from the worst infestations, including at Hampshire, it is good to see there is a longer term concerted effort to contain it from spreading further. Hopefully that work can complement a new round of successful biological control that may eventually eliminate, or at least get on top of the current eye sore and impact of dense thickets over large areas.

The Gorse was very bad in Waratah a few years ago, but its nearly all gone now due to some hard work by a few people.

Pre Gunns and Forico we had some focus on gorse. We sprayed with a mix of chemicals, burnt, tilled the soil to promote seed germination that I understood could remain viable for 80 years. We were patient as we were with getting on top of white grass and lilly grass.

White grass removal was important at higher altitude because once dead it reflected the sunlight, impacting soil warming in areas of limited growing seasons. It needed to be killed and then burnt. The stuff is so full of cellulose that incorporating into the soil would seriously deplete soil nitrogen.

I remember discussing all this work with some company directors in front of David Bills and I commented that much of our plantation programme was a large experiment developing new techniques to allow us to successfully establish productive first rotation plantations in a challenging environment. Billsy nearly fell off his chair with the thought of such an expensive experiment. It was well worth it.

I heard some stories that gorse was also used around the convict road area around compounds … for convict workers? Maybe old wives tales.