Introduction

The South Australian portion of the Nullarbor Plain was part of New South Wales. The reason can be explained by examining the stories behind the development of each of the state borders since colonisation. This blog will initially focus on the creation of the Western Australian, South Australian and Northern Territory border, which is now on the 129 Degrees East longitude (1290E) but was initially further east. It then highlights the problems in trying to accurately survey a border that bears no relationship to geographic features on the ground – a big problem when the border is over 1,800 kilometres long and represents the longest straight line in the world.

Captain James Cook had “taken possession” of the whole eastern coast of Australia in 1770 without giving it a name, nor did he define any western boundary, thus making his claim on behalf of the King somewhat obscure.

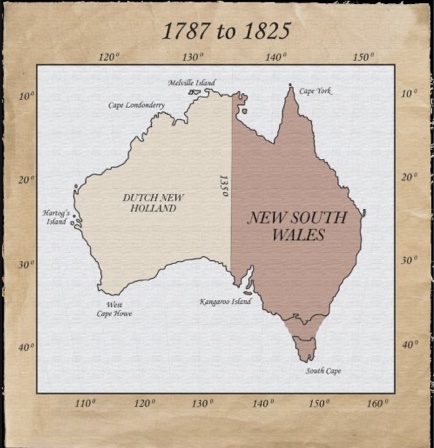

With the first fleet’s arrival on the east coast in 1788, the British Government claimed possession of Terra Australis westwards to the line at longitude 135 Degrees East (1350E) through royal commissions issued to Captain Arthur Phillip. This land was known as New South Wales, and the remainder of the continent became known as New Holland.

Many believe that choosing 1350E was not arbitrary, but there is no agreement on why it was picked. The most plausible explanation I have read concerns the international politics of neighbouring countries to the north of Australia. The Portuguese had been in Timor since 1516, and the Dutch since 1686. Both had rights through their settlement, but it was unclear how far those rights extended on the Australian continent.

The cooperation and pleasant dealings with both Portugal and Holland were essential for the success of the First Fleet and the settlement at Port Jackson. The British were worried that if they defined their boundary too close to Port Jackson, the threats would be harder to defend from every direction.

In determining the western boundary, 1350E was considered more favourable because it was not only the true antemeridian of the Tordesillas Line via a treaty between Spain and Portugal, but it kept the north-south boundary of New South Wales a reasonable distance from Timor. And besides, anywhere further west was considered too close to Timor and could be challenged by resurrecting Captain Cook’s initial and vague claim.

While no claim was laid to the remainder of the continent known as New Holland by any nation, despite several landings by Dutch, Portuguese, French and British navigators, the British feared the likely occupation of the north coast by the Dutch or the French. This prompted them to establish a settlement at Fort Dundas on Melville Island. But the western boundary became an issue because Melville Island was a few degrees west of 1350E and wasn’t within the New South Wales territory.

Consequently, the New South Wales western border was moved to 1290E in 1825 as part of the royal commission associated with the appointment of new Governor Ralph Darling.

The creation of Western Australia

Meanwhile, sovereignty over the continent’s western half was left in abeyance. The Dutch had explored much of the west coast but showed little interest in making any claims over the land. On the other hand, the French had sent several scientific and exploratory expeditions to the area. On one of those expeditions in 1772, Commander Louis Francois Marie Aleno de Saint Alouam claimed the land for King Louis XVI. However, he died in Mauritius before returning home, plus the French revolution removed any serious interest in colonising the new territory.

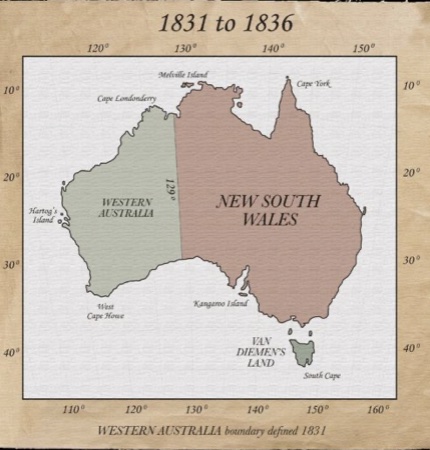

Notwithstanding this, the British were anxious about the intentions of the French in the future. As a result, the British Admiralty was instructed in 1828 to take possession of the western coast of New Holland. The first settlers arrived in the privately financed Swan River Colony the following year, and Captain Charles Howe Fremantle took formal possession of New Holland.

Lieutenant-Governor James Stirling arrived soon after to take control of Britain’s newest southern colony without government support or convict labour. His authority was confirmed as:

“…from Hartog’s Island to 1290 East longitude”.

At this time, no other mainland colony had been created by separation from New South Wales. Of course, as the maps above show, the island colony of Van Diemen’s Land had been established, separate from New South Wales.

The creation of South Australia

But not long after, a group of entrepreneurs called the National Colonisation Society began private negotiations with the Colonial Office in London for a new colony on the Australian continent in 1831. They proposed a social experiment based on the theories of Edward Wakefield and his systematic colonisation that involved land sales, free labour and a concentration of settlement. Like the Swan River Colony, it was approved on the proviso there would be no cost to the British government.

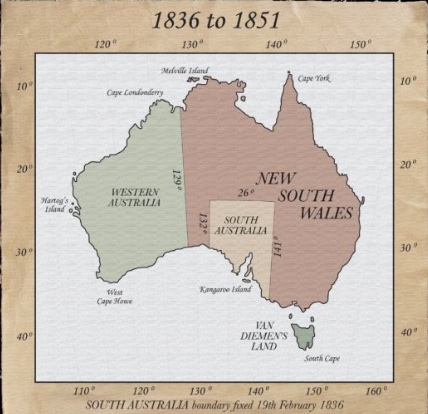

A territory between the 132 and 141 meridians was recommended during the initial discussions. Not much of their proposal was adopted by the British Government, but they agreed on the original proposed east and west boundaries. Mind you, no northern boundary was seriously considered because no-one had any idea what lay in the continent’s interior. It has been suggested the 26th parallel latitude was selected as it was near enough to the halfway point of the continent.

Unbeknownst to New South Wales, the British Parliament passed legislation in 1834 defining a new colony:

“…on the 260 of South Latitude, on the South of the Southern Ocean, on the west the 1320 of East Longitude and on the East the 1410 East Longitude”.

In 1836, the colony of South Australia was proclaimed. However, its western border at 1320E left a strip of land, referred to as “No Man’s Land”, in the hands of New South Wales between the South Australian and Western Australian colonies. It is unclear why 1320E and not 1290E was chosen for the western boundary of South Australia.

It is believed to be connected to the lack of a safe harbour at the head of the Great Australian Bight from Matthew Flinders’ discoveries. Fowler’s Bay lies a little to the east of 1320E, and it was the only anchorage available in the area. The coast at 1290E comprises part of the spectacular and inaccessible Bunda Cliffs. Thus, from Flinders’ journal, the coastline east from Fowlers Bay to the Spencer Gulf provided many more opportunities for shipping and trading.

During the 1800s, there were many epic land explorations as each colony sought to find suitable land to establish agricultural and pastoral bases to support their economies.

The settlers in the newly established South Australian colony soon looked to the west, and in 1840, Edward John Eyre made his infamous trek across the Nullarbor Plain to Perth. However, his pessimistic report squashed any expansion plans westwards until minor exploratory work on the Eyre Peninsular showed promise.

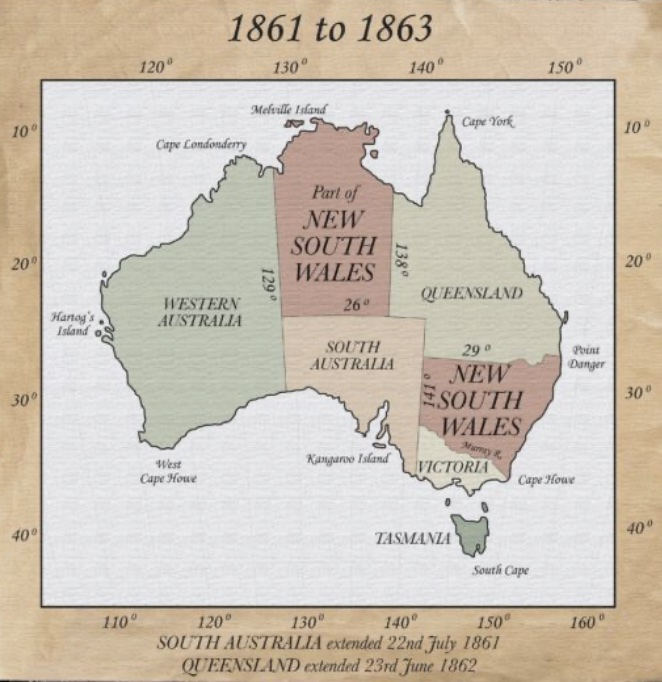

The South Australian government determined that the area towards “No Man’s Land” would be settled by pastoralists, and the nearest ports for shipment of produce from the area would be within South Australia. The New South Wales Government agreed realising that part of the land was useless to them and would only prove to be a financial burden in the future. In 1858, South Australia successfully petitioned to annexe the “No Man’s Land”. It was formalised in 1861.

Early survey work

The next part of the story gets very interesting. Bear in mind geographical features are the favoured means to determine boundaries. The primary reliance on meridian lines of longitude, which are measured from the datum meridian at Greenwich by the British before international acceptance in 1884, and parallels of latitude, which are measured from the equator, in determining the majority of the boundaries between each Australian colony, can probably be explained by the fact the geography of the interior of the continent was unknown at the time, and it was quick and convenient to do so.

However, marking those “celestially-described” straight lines in the field was not an easy exercise.

The first attempt by surveyors to place markers on the South Australia-Western Australia boundary occurred in 1866. They traversed westwards from Fowlers Bay, approximately 330 kilometres, via a chain and prismatic compass survey to the border. In doing so, Surveyor-General Edmund Delisser identified a safe harbour near the Eucla sandhills, which he believed was in South Australia. He recommended a marine survey so South Australia could take advantage of pastoral development.

President of the Marine Board, Lieutenant Douglas carried out a marine survey of the area in May 1867. As a result, he placed a cairn on the border near the cliffs. On the centre pole was the following inscription:

“South Australia. Province Marine Survey – Lat 31041’0.85’’: long 12900’00” East; var 1052’ East. Being the boundary between the Provinces of South and Western Australia”.

A later revisit of the Delisser survey to compare with Douglas’ Cairn put it at 129001’54”E, inside South Australia. It was apparent from this that the potential new harbour at Eucla was in Western Australia.

In 1880, Captain Howard in H.M.S. Beatrice visited the area and claimed the cairn was situated at 128059’58”E, just inside Western Australia. Other readings which varied from these two, and from each other, were calculated using the trigonometrical networks from Perth and Adelaide.

It was becoming quite clear by the turn of the century that the location of 1290E had to be determined in the field. Western Australians were leasing land up to the Douglas Cairn, which the South Australians believed was at least 800 metres inside their territory. Nothing eventuated, much to the chagrin of the pastoralists. There was a similar situation in the north where pastoralists had settled on land as far as 450 kilometres from the coast. They were anxious to fence their properties that adjoined the Northern Territory of South Australia.

In 1907, after Federation, an agreement was reached to construct a Trans-Australian Railway, which attracted surveyors to the area. The Engineers Report to the Federal Parliament referred to a substantial cairn built on the border “which can readily be seen one mile from any direction”. The railway surveyors determined the Douglas Cairn longitude as 128059’37”.

The Deakin Obelisk

While arguments over the exact location of the border in the field dissipated, a decade later, South Australians were still keen to see a permanent marking of 1290E in the field, particularly from the southern coast north to about 80 kilometres north of the Trans-Australian Railway.

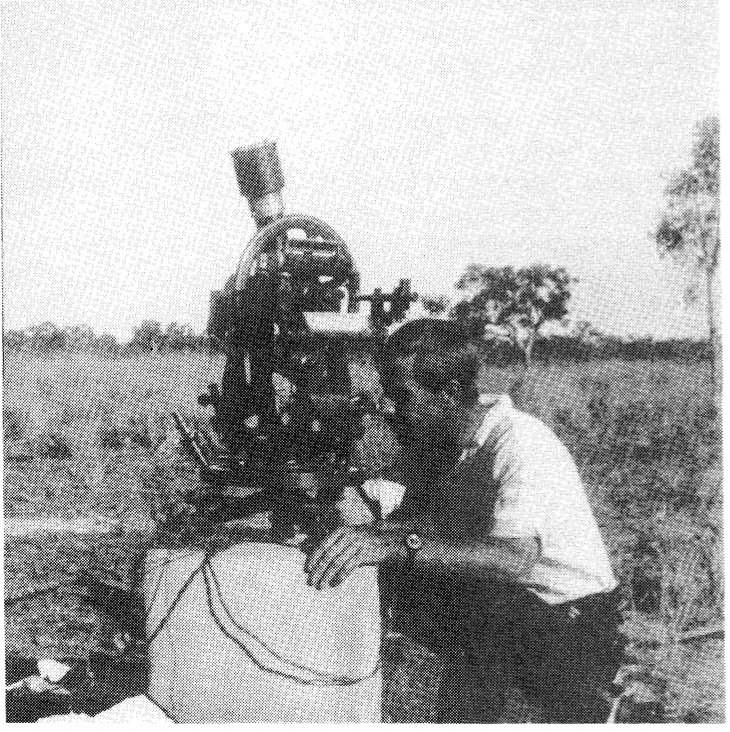

After a trial which enabled the successful transmission of radio-telegraphic longitude signals directly from Greenwich, the South Australian astronomer George Dodwell and surveyor Clive Hambidge went to the Deakin siding closest to the border in October 1918.

They set up three observing pedestals to take astronomical observations to fix longitude using three different methods. It proved successful, and more extensive observations were carried out in April 1921 at the Deakin siding. The value of the East longitude of the pedestals was calculated to be 128058’00”.63, making them about 2.8 kilometres west of the border.

The Austral Pillar

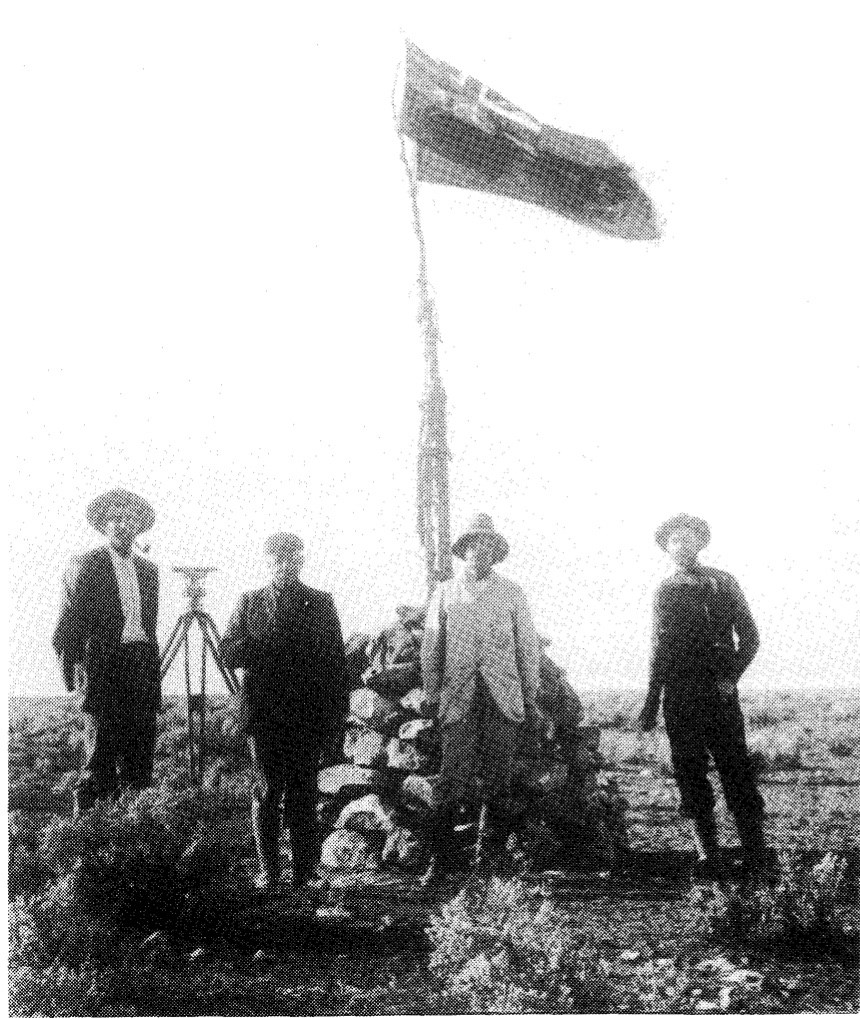

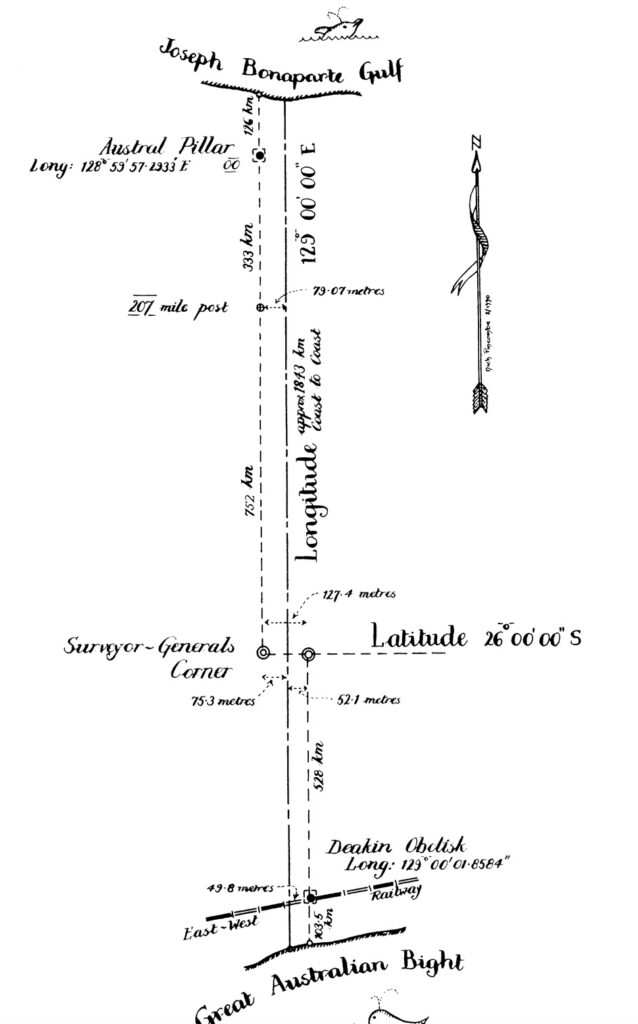

After his work at Deakin, Hambidge travelled to Wyndham with Western Australia’s astronomer, Harold Curlewis, in June of that year. On the Durack station at Argyle, they set up wireless masts and aerials, which they considered close to 1290E, and astronomical observations were made. Preliminary results showed that they were about 11/2 miles east of the border. The Austral Pillar was installed at a longitude now accepted as 128059’57’.2933E.

The 1922 Agreement

Following this work, an agreement between Western Australia, South Australia and the Commonwealth, which had taken over management of the Northern Territory from South Australia, later that year agreed on a process to determine the accepted legal position of the border separating them.

The agreement included permanently marking on the ground, to its best ability, the position of the 1290E. This was done via the Deakin Obelisk and Austral Pillar. The object of the agreement was to use these two markers as being on the 1290E and to run lines true north and true south to the 26th parallel South latitude. This meant, in practical terms, since neither monument sits on the true 1290E meridian, the straight line connecting them calculates about 02” from true north.

But as any surveyor would appreciate, this was a problematic surveying exercise and very much dependent on the accuracy of survey equipment in 1922.

By 1990, marking on the ground had been carried out for 333 kilometres south of the Austral Pillar to the 207 Mile post and 126 kilometres north to the coast. Because fixing of the survey south from Austral Pillar was carried out true south and not towards the Deakin Obelisk, the 207 Mile post is about 26 metres west of this line, while the survey north places the fence about 10 metres east of the line at the Joseph Bonaparte Gulf.

Surveyor-Generals Corner

In 1963, it was decided to mark the 260S parallel of latitude representing the South Australian-Northern Territory border, with the termination of the survey at 1290E, shown by a permanent obelisk on that meridian.

In 1967, the Director of National Mapping was concerned that because the longitudes of the Deakin Obelisk and Austral Pillar were not the same, “there would be a permanent reminder of the inaccuracies of early surveys”, much the same as the problems with the South Australian-Victorian border.

His concerns were rejected mainly because nearly 300 miles had been marked and adopted at the northern end as the boundary and improvements had been erected, and the boundary fenced. In other words, they were very reluctant to try and fix the problem where the boundary on the ground was not in the exact spot it was supposed to be.

Therefore, it was decided to place two marks at Surveyor Generals Corner at the 260S latitude – one due north of the Deakin Obelisk and the other south of the Austral Pillar.

By doing this, a 127.4 metre step in the eastern boundary of Western Australia was defined.

Conclusion

The Western Australia, South Australia and Northern Territory border line on 1290E meridian longitude is 1,843 kilometres long. It is the longest “surveyed straight line” in the world, beating the next longest line separating the border between Alberta and Saskatchewan in Canada at just over 1,200 kilometres long. However, on the ground, it is not straight and can only be explained by a surveyor who understands the complexities of trying to fix a celestial line on the ground.

I understand that GPS surveys were carried out in 2012 at the Deakin Obelisk and Austral Pillar to determine the accuracy of the two original surveys. Regardless of what they found, if the principle of the 1922 Agreement still stands, and both markers represent the 1290E in the field, then the borderline, which is represented on a map as a straight line following a particular meridian longitude, is not a straight line in the field.

Bear in mind, this is not unique. No measurement is perfect, whether it’s the calculation of longitude at a specific point, or the marking out of a line of longitude or any other boundary, once it’s marked on the ground and accepted by both parties on either side, it becomes the boundary. It’s a matter of legal precedent and that is what the 1922 Agreement achieved. But I thought this story would highlight how difficult it is to mark lines in the field that represent straight lines on a map, as well as providing some interesting history about our state borders.

Thank you Robert, now I know why my road line on Woolnorth never worked out.

Informative and borderline entertaining.

I think we are seeing the emergence of the Southern Hemisphere’s “Simon Winchester”!

I often wondered how the borders were set. This does explain the great difficulties they have had.

Very interesting, thank you Robert.

Great post Robert.

I celebrated my 60th birthday at Surveyor Generals’ Corner because of its interesting but little known background.

Three other foresters were with me. Perhaps this reflects foresters’ broad interests. The nearby community of Wigellina/Irruyuntu was very hospitable.

There are rich nickel resources in the Peterman Ranges so far protected by remoteness.

You are correct to mention the Tordesillas Line Robert – according to men in tights and wielding swords, in any civilised world we Western Australians should be pledging our allegiance to the King of Portugal and the rest of you people on this continent need to bend your knee to the King of Spain.

Anyone who wonders about Westralian secessionist tendencies needs to know it has a VERY long history. Splitting (Portugese) Brazil from the (Spanish) rest of South America has surprising resonances half a globe away.

To make another ‘Westralian point’, the change from 135 degrees to the current 129 degrees comes as no surprise – you’ve pinched our GST for years; so hearing about our land previously being nicked as well is hardly an earth-shattering revelation.