I first learnt about the Bush Church Aid Society (BCA) when I researched a story on pilot John Lindridge, who worked for BCA in the 1960s. While this story mentions the skills of the original pilot Allan “Chaddy” Chadwick, John Lindridge was also a very competent and professional pilot. My blog about John provides more details on his remarkable career and tragic end.

While some people may have strong views on the patronising influence of the church on indigenous communities and their role in converting many to Christianity without recognising their own spiritual beliefs and connection to the land, there is no doubt the BCA played a remarkable and benevolent role in outback South Australia, mainly through their medical services and flying support over vast areas without government assistance. They successfully treated various illnesses and helped save the lives of several people. I am not religious, but I admire the people who lived selflessly in very remote areas to provide much-needed medical service for the local inhabitants.

The BCA still operates, and its main aim is to provide strong support networks by placing Christians in sparsely populated areas to provide teachings of Christ, and giving care and advocacy services. But in some remote outback communities that no longer have missionary zeal and comfort, there are numerous problems.

I am sure many readers may not have heard of the Bush Church Aid Society (BCA). BCA is a Christian ministry that has provided religious education, flying padres and counselling, welfare and medical services across outback Australia for over a hundred years.

Its origins were born out of a vision to provide pastoral and spiritual care for the indigenous inhabitants and new settlers in remote areas of Australia.

It started as an offshoot of the Colonial and Continental Church Society (CCCS), which began in the Swan River Colony in Western Australia in 1836. In 1919, missionary Sydney James Kirkby was tasked to assess further opportunities for missionary work of the CCCS across Australia. In particular, he saw a need for hospital and nursing care in the outback. So, on 26 May 1919, 26 people gathered in Sydney to establish the BCA.

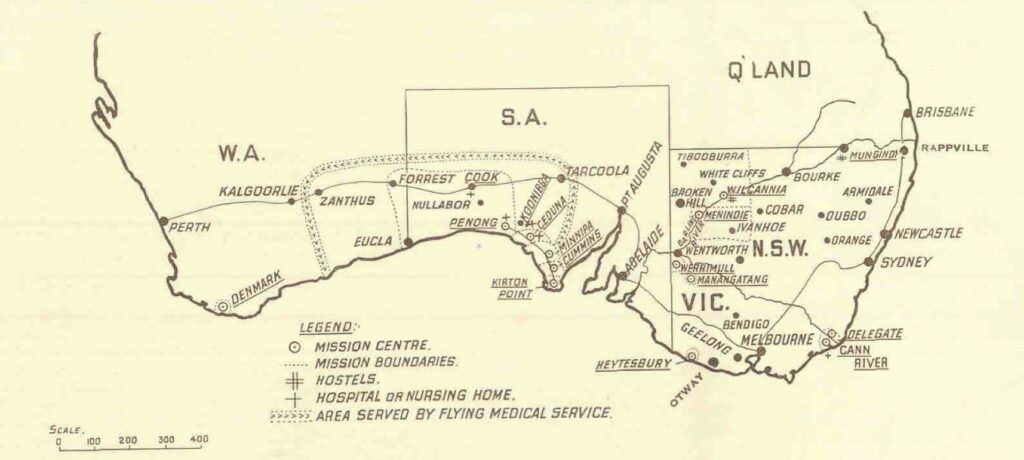

After only 21 years, it had established and staffed 14 missions, four hospitals, two nursing homes, three children’s hostels, a mail-bag Sunday school and a medical air service. It was the largest single organisation of its kind in Australia. What’s more, they funded their operations free from government support.

BCA operated and flourished when over 40 per cent of the Australian population were Anglican. That figure today is only 18 per cent, although the proportion of Anglicans has increased with the population growing from just over 5 million then to now nearly 25 million.

One big focus in the early 1920s was hostel accommodation and support for children who had to leave home for their education.

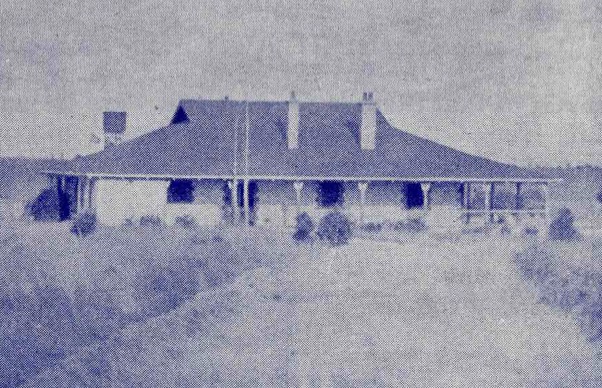

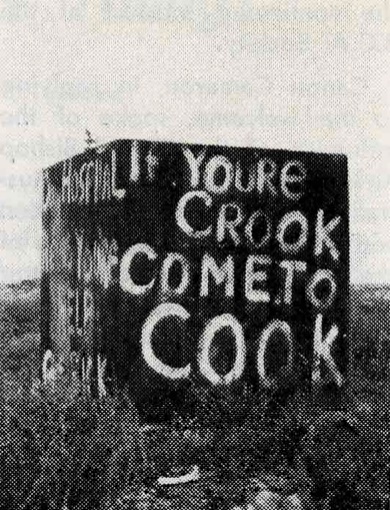

Ceduna was the headquarters for all BCA’s medical work – there were doctors and nurses and a dentist, pharmacist and radio operator. A second hospital was opened at Penong in 1927, a third at Cook in 1937, called the Bishop Kirkby Memorial Hospital, and in 1938, a fourth at Koonibba.

The early population was small, and health services were non-existent. Nurses were provided under the Farmers Medical Society (FMS) as the population grew. The BCA became involved in late 1925 when a small farmhouse in Ceduna became the town’s first-ever cottage hospital. It soon extended its services to Cook on the Trans-Australia Railway, midway between Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. BCA became the primary outback health provider, leading to the FMS’s dissolution. BCA provided a health missionary for over 40 years.

For many nurses, the work was a calling, with some staying a long time. Sister Doris Percival from Sydney was the first to reside in the galvanised iron building, with just one hospital bed, a cupboard made of petrol cases and a primitive stove. The hospital soon had ten beds, four bassinettes, and a small operating theatre within a year. The new Matron was the formidable Florence Dowling.

Grace Hitchcock was a typist in Melbourne when she wrote to Kirkby in 1922 to offer her services. It took her ten years to get her double nursing certificates, and she arrived at the Ceduna Base Hospital in 1933. After that, Grace moved to the Penong Hospital and, in 1938, to the Kooninbba Mission Hospital.

The nurses made the most of what they had living in isolated places on the Nullarbor and beyond. For example, when a high-level party of BCA executives were flown into Cook in the 1960s, the nurses served them a buffet dinner – a remarkable achievement to supply a varied menu. The party were then treated to a large pavlova decorated with a plentiful supply of luscious strawberries from the hospital garden in the middle of the Nullarbor arid plain.

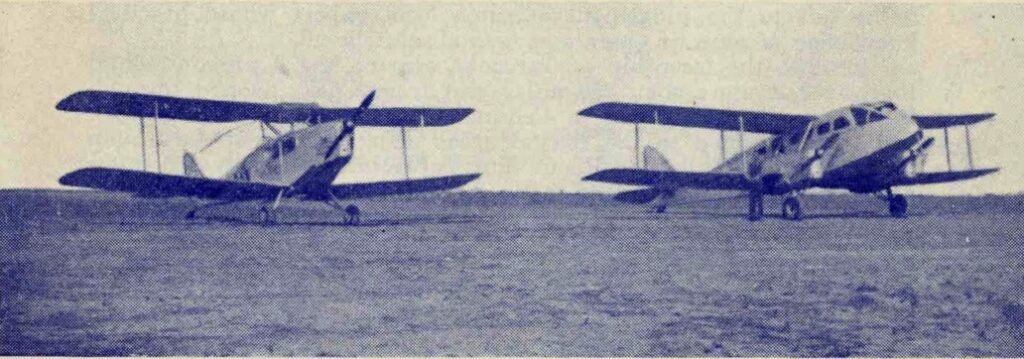

In 1934 husband and wife doctors Roy and Freda Gibson arrived, and they were successful in lobbying for a new bigger hospital and an air service. The struggle to cover the enormous distance to Cook by car over the Nullarbor’s stony tracks quickly became a barely impossible task for Doctor Roy Gibson. Nine years earlier, Australia’s first aerial medical work had started at Cloncurry. For the new Flying Doctor Service base at Broken Hill, the Commonwealth Government ordered a de Havilland 83 Fox Moth. The well-proven Fox Moth could carry a stretcher as well as two passengers. BCA saw this aircraft as the solution to Dr Gibson’s transport problems between Ceduna and Cook.

After the flying pastoral ministry’s success, BCA set up a medical missionary plane in 1938. Alan “Chaddy” Chadwick was employed as BCA’s first pilot. He took delivery of a de Havilland Fox Moth in Sydney and flew it to Ceduna to start services.

“Chaddy” learnt his way around South Australia outback in goggles and helmet in the open cockpit of the Moth, using a school atlas. He was a perfectionist, and his insistence on flying safely became legendary.

In his first year, “Chaddy” flew over 13,000 miles with 1,017 patients treated. It began South Australia’s extensive Flying Medical Service network, which eventually was incorporated into the Royal Flying Doctor Service’s operations in 1968.

Initially, the medical service operated between the BCA hospital in Ceduna and the outlying hospital in Cook. By 1944, the reputation of this service spread, and medical services were established across outback South Australia. It soon became an efficient operation in western South Australia, servicing five hospitals spread over hundreds of square kilometres.

“Chaddy” told one of his many experiences in the excellent BCA newsletter called “Real Australia” in 1951 and is an example of the sort of work the BCA carried out as part of its Flying Medical Service in isolated places in South Australia.

A major burning incident occurred at Mt Eba. The wife of the air radio operator suffered severe burns on her face, arms and legs.

After a floor mop had been cleaned in petrol and hung out on the line to dry, she decided to complete the cleaning process by boiling it up in the copper. As the mop was immersed in hot water, the strands spread out and released some particles of petrol that must have been held at the base of the mop. As they broke the water’s surface, the copper fire ignited the vapour, and the flash severely burnt her.

“Chaddy” flew the doctor to Mt Eba to find the patient heavily bandaged and so severely burnt about the neck that she had almost lost her voice. The doctor carried out emergency treatment on the spot, and then making her comfortable on the stretcher, they flew back to Ceduna, where skilled hospital treatment was available. Even though more than forty per cent of her body area was affected by the burns, her progress was remarkable, and at the end of a month, she was convalescent and ready to return home again.

The Fox Moth was fitted with a single Gypsy Major four-cylinder engine which drove a six-foot diameter propeller and developed 130 horsepower for take-off. Petrol was carried in a 20-gallon tank in the centre section of the upper wing and piped to the engine under gravity. Three passengers somehow squeezed into the tiny cabin – two hammock-like seats and a third “dicky”-type seat facing the rear, but the pilot had to brave the elements by himself in an open cockpit behind the cabin.

The late 1930s saw the beginning of radically new designs. The successful all-metal monoplanes were the death knell for the familiar old wood and fabric, wire-braced biplanes.

After WWII, there were many opportunities to purchase surplus aircraft at a price much less than their original cost. Consequently, a second medical aircraft, an ex-RAAF twin-engine de Havilland 84 Dragon, was purchased in 1947 to replace the Moth. Its principal advantages as a medical service aeroplane were its carrying capacity, roominess, twin engines and operating range which allowed return trips from Ceduna to Cook without refuelling at an outback centre. The Dragon flew 30,000 miles and saw 1,600 patients each year. But for the pilot, gone was the open cockpit, helmet, goggles and flying suit.

Remarkably, both were biplanes whose era was popular up until the commencement of WWII.

During take-off, the passengers had to lean well forward to ensure the aircraft’s correct fore and aft balance. Nevertheless, it held pride of place on the Australian Civil Aircraft Register as VH-AAA.

The growing network of medical assistance was extended to include several station properties, the Coober Pedy Opal Fields, the AIM hospital the Reverend John Flynn had founded at Oodnadatta in 1912, and the other bush hospitals at Penong, Tarcoola, Wudinna and the Koonibba Aboriginal Mission. Although the BCA hospitals could treat most ailments, particularly in Ceduna, patients were transported to Adelaide when speciality treatment was needed.

Tragically, Doctor Roy Gibson died in 1948, aged only 43. Dr Merna Mueller initially arrived as the locum to replace Roy. Fortunately, she stayed with Freda and the nursing staff, and they provided a reliable and excellent medical service until 1968.

One great example of the service provided by the BCA flying medical service involved the sheep stations surrounding Tarcoola. Station workers and families had to travel long distances to Tarcoola to see the doctor on their visiting day, leaving early in the morning.

The doctor was flown from Ceduna, but the weather was always a hindrance, particularly dust storms and strong winds. As a result, the flights were cancelled several times at the last minute. Station folk then made their trip in vain because they could not be contacted once they left the stations. To avoid all the uncertainty about travelling to Tarcoola, the BCA negotiated with the Mulgathing Station, which had an excellent landing strip near the homestead, to provide a monthly visit as part of the outback rounds.

However, by 1954 the demands on one pilot and one aircraft at Ceduna meant a second pilot and plane were required. The BCA purchased a Percival Proctor Mark III. Like the Dragon, it had been built during the war for service use, initially as a training machine for aircraft-carrier flying techniques and later as a light transport aircraft for VIPs.

While the Proctor was a good plane for pilots, it was not popular for passengers. It was never stable in calm conditions, bucking and tossing violently in any turbulences and constantly tested the propensity of passengers to withstand air sickness.

Even though the Dragon-Proctor partnership worked well over four years, with the Dragon taking on most of the longer regular medical flights to Cook, Tarcoola, Coober Pedy and Kingoonya, with the Proctor on stand-by for the urgent emergency call, the ageing Dragon was replaced by a Lockheed 12A in November 1957. The Dragon proved to be a magnificent high-performance aircraft that almost doubled travelling times. Both aircraft carried out 200 flights, covering 45,600 miles with over 2,500 patients treated.

In March 1960, the Lockheed was extensively damaged in a crash at Ceduna aerodrome. The accident occurred when the aircraft’s starboard undercarriage leg collapsed immediately after landing.

The port leg also gave way, and the plane crashed down and skidded on its fuselage, coming to rest on its nose with the tail in the air. The undercarriage mechanism, port engine mountings, support bulkheads, and propellers were damaged. No one was injured.

Due to its age and increasing demand for replacement parts, BCA investigated a replacement option.

The Cessna 210 was purchased as a modern plane that could accommodate stretchers loaded through a separate luggage hatch without modifying doors or its structure.

With the increased demand to service the vast outback, BCA decided to employ a second pilot in 1961 and purchase a second Cessna. While the area serviced initially extended as far west as Cook and north to the trans-continental railway, it now stretched north to Oodnadatta, west to Forrest and south to the lighthouses near Kangaroo Island. The new pilot, John Lindridge and the original pilot, “Chaddy”, were flying 10,000 kilometres a month.

In 1966, BCA carried out investigations to replace the Cessnas. John researched and recommended the six-seat Beechcraft Baron B55, which had proved its worth in medical flying with the Royal Flying Doctor Service in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. Financing was covered by the trade-in of the Cessnas and a generous legacy left to the BCA by a supporter. In addition, the Baron was much faster, reducing the flying time from Ceduna to Cook from one hour twenty minutes in the Cessna to one hour.

By late 1967, a Special Meeting of the BCA Council had to consider a report regarding the Flying Medical Service. Their remaining doctor, Dr Mueller, took some time off from the arduous and demanding task for over 15 years and then decided to resign and take up the Ceduna medical practice full-time. While this allowed BCA to give more attention to the remote areas in its network, BCA struggled to retain the services of a full-time doctor. They faced a serious situation when the temporary replacement stayed for one week after virtual inactivity whilst responsible for attending to remote work only. This, coupled with the dramatic drop in radio work following the installation of a PMG radio phone at Coober Pedy, meant it was unlikely the BCA could justify maintaining their service.

BCA claimed that the pioneering work it had set out to do in 1937 had been achieved. Moreover, the Port Augusta Base of the Royal Flying Doctor Service, established in 1955 as a radio base, was now equipped with modern aircraft and could cover the network the BCA had served for so long. Accordingly, they decided that the whole BCA flying network would be transferred to the Royal Flying Doctor Service early in 1968.

The BCA still operates today in its missionary working recently celebrated 100 years in service. From small humble beginnings, it has a network of charitable services across the whole continent and Tasmania. Why this important Christian organisation is not recognised for its important work by historians, governments, the media and bureaucrats is a mystery.

Another interesting historical record of a group of very dedicated Australians.

Thank you Robert. A most interesting article! BCA is involved in several parishes in Tasmania and remains a key support in Gippsland following the bushfires of a couple of years ago. https://www.bushchurchaid.com.au/content/bca-reconnects-with-croajingolong/gjkqol

Thanks. I am Peter Job, the son of Mac Job (as he was known) who you mention in the photo. Dad flew as a BCA pilot from 1955 to about 1962.

I remember Alan Chadwick quite well from my childhood. Although the family left Ceduna when I was very young, Alan and dad used to catch up a lot. The name John Lindridge certainly rings a bell too, and I think I met him as a child, although not as often as John Chadwick.