“Think of forests of WA and you picture the green south-west; think of Kalgoorlie and you conjure thoughts of gold, not trees. But the green and gold are inseparable. The trees that kept the hearts of the mines pumping were cut from native woodlands miles from the goldfields and hauled along specially constructed bush railways”. Cliff Winfield

Introduction

When I first visited Kalgoorlie last October, I read about the Great Western Woodlands. Based on their distribution and extent, they certainly are “Great”. The Woodlands cover nearly 16 million hectares south and west of Kalgoorlie. They include around 10 million hectares of woodland, 1.6 million of mallee, dominated by multiple-stemmed eucalypts, 3.2 million hectares of shrubland and 1.1 million hectares of bare areas and grassland. Nowhere else in the world will you find so many different trees in such an arid climate. They contain an astonishing one-third or about 300 species of eucalypts. I read that they are the “largest remaining area of intact Mediterranean climate woodland on Earth”.

Until recently, though, the woodlands were known as the Goldfields Woodlands. Why the name change? Well, in the hard-fought state election campaign of 2015, both the Liberal-Nationals coalition and Labor made similar promises to spend money on conservation programs attempting to win over the votes of the city residents. After Colin Barnett became Premier, his government allocated $3.8 million towards a Biodiversity Conservation Strategy for the Goldfields Woodlands. The Wilderness Society came up with the “Great Western Woodland” moniker, and it stuck.

As with many interpretive signs about the natural environment these days, the central theme is protection and preservation. Specifically for the Great Western Woodlands, there was a strong emphasis on “protecting its value as an intact and essential ecosystem”. My interest was piqued because, while the woodlands essentially cover uninhabited country over a massive area, they extend right through the eastern goldfields of the state. Surely, I wondered, the woodlands must have had some disturbance, at least in some areas.

I did a google search on the Great Western Woodlands. The most prominent websites are non-government organisations with a preservation bent and Wikipedia parroting what the former sites claim. For instance, The Wilderness Society uses hyperbole to try and attract donations “to protect the woodlands and combat the impacts of climate change.” They claim the Great Western Woodlands, compared to similar landscapes elsewhere in the world, “remains relatively unspoilt, making the region of both national and international significance” and mining “threatens to fragment” the woodlands. The Wilderness Society says they are working with “First Nations people, local stakeholders and the WA Government to create new economic opportunities…ecotourism trails, community festivals, renewable energy and sustainable land management”.

I thought it was strange to raise a possible future threat of mining, mainly as I believed gold and other mining in the last century already had an impact. But being a professional land manager myself, the final economic opportunity they mentioned caught my attention – sustainable land management. Nowhere in their linked Framework document do they specify any practical land management practices to save the woodlands. There are the usual motherhood statements about maintaining ecological integrity, population viability, recognising the natural environment and using ecological integrity thresholds (whatever that means) to assess and guide economic development options. There is zero discussion on what strategies should be implemented to achieve those admirable goals.

Other web pages have a similar theme – the largest, healthiest intact woodland on earth teeming with wildlife, particularly birds. CSIRO even claim that the incidence of larger, more intense wildfires in recent years has “caused fire-sensitive old growth woodlands to be lost at an alarming rate”.

However, I uncovered a much different narrative upon reading and researching more about this vast landscape. The eucalypt woodlands of the goldfields are a true marvel of nature, but they are not a landscape that has withstood the pressure and impacts of European settlement, and they are certainly not “intact”. Instead, we see today an artefact of 120 years of grazing on pastoral leases, mining, infrastructure development, changed fire regimes, pests and weeds and timber harvesting, including a rapacious firewood gathering spree unsurpassed anywhere in the world during the last century. However, where timber was harvested, it has led to a healthy, vibrant regrowth woodland community that we see and celebrate today, rather than a delicate environment in need of saving.

Indeed, the success of Western Australia’s gold mines would not have been possible without firewood from these vast woodland areas. Without the salmon gums, gimlets and mulga of the goldfields, the miners would have had to find alternative fuel sources or move timber from the south-west forests in massive quantities to support the lucrative gold mines.

The truth is many of these non-government organisations, academics and government agencies do not understand or report the true history of the woodlands. They are clueless about how they function, and they are bereft of any idea on how to manage them properly. And I am sure it would be not only a surprise but also an annoyance to these organisations that the original person responsible for highlighting the significance of the Goldfields Woodlands and taking steps to conserve and manage them was a professionally trained forester by the name of George Brockway.[1]

The reality is the woodlands do not need saving. They have never been under threat, despite a history of intense utilisation.

The Woodlines and their impact[2]

The development of the goldfields from the 1890s created a huge demand for timber for mining and fuel. The big company mines needed a source of cheap energy for steam-driven winders that hauled the gold-bearing ore to the surface and to feed the sulphide roasters that processed the ore. They also needed material for mine construction and support in the underground tunnels and shafts. Coal was too expensive, and so timber was favoured. The rapidly growing population also needed firewood for domestic use to fuel the condensers that supplied fresh water to the goldfields and to generate electricity.

By 1900 timber close to Kalgoorlie had been cut out. Over 1,200 tons of wood a day was used at the gold mines and towns.

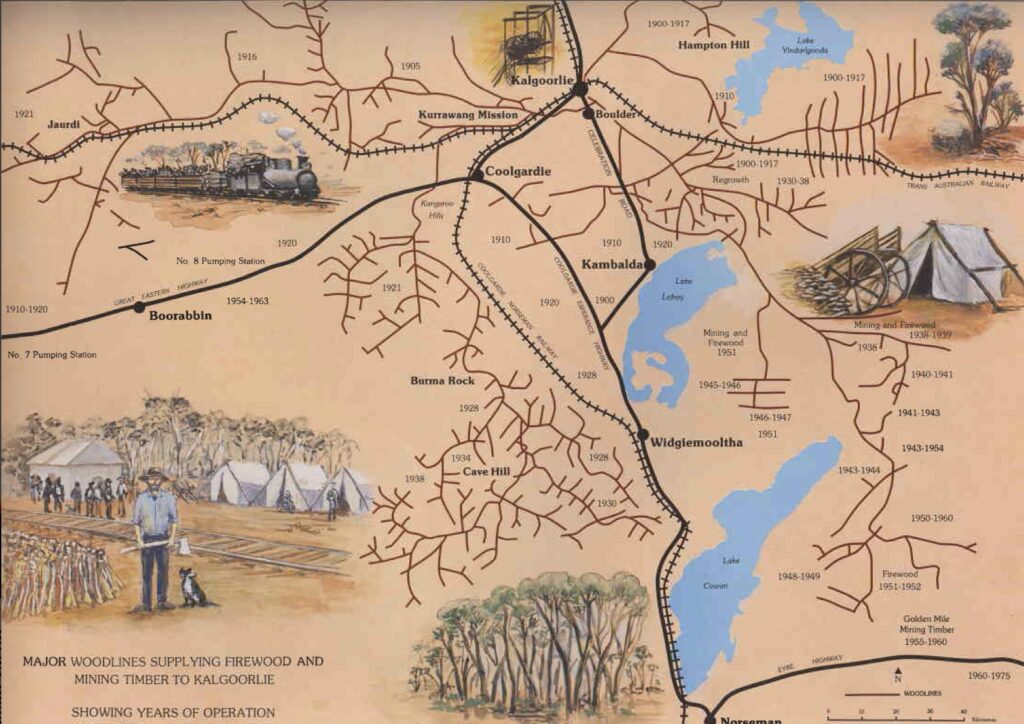

An elaborate light rail network, known as woodlines, radiated out from the Golden Mile to the south and west of Kalgoorlie into the surrounding woodlands to power the mines. In the early years of the Golden Mile, two wood corporations were largely instrumental in developing the timber supply for the mining industry in Kalgoorlie. They were the West Australian Goldfields Firewood Supply Company (WAGFS) at Kurrawang, about 14 kilometres east of Kalgoorlie, and the Westralia Timber Firewood Company at Kurramia, near Kanowna north of Kalgoorlie, which only operated for about 15 years. The former company ran its own self-contained industry and built a small town to support it. It had a well-equipped workshop at Kurrawang to repair and fit the rolling stock, from locomotives to trucks. They ran a sawmill to make sleepers from salmon gum. They also provided stores at branch camps to supply food for the bush workers. They even slaughtered their meat and made their bread.

Over a vast stretch of the country surrounding Kalgoorlie and Boulder, the woodlands consisting of belts of mulga to the north, salmon gums, gimlet, and many other eucalypt species were the supplier of firewood and props for the mines. Salmon gum was utilised for firewood because of its favourable calorific value. Wherever the cutters went, the removal by clearfelling of vast quantities of timber changed the woodlands, and in some places, severely denuded the landscape of vegetation.

WAGFS was one of the largest woodline companies to operate in the area. They secured a concession over a considerable tract of land, 160 square kilometres, reaching almost as far south as the Eyre Highway (an area 1.2 times the size of England). During its first decade of operation, the company produced over 2 million tons of firewood, averaging 18,000-20,000 tons per month, employing 450 cutters, 30-40 truck loaders, 40-50 horse drivers and 100 horses. In addition, they ran eight locomotives on the woodlines. In that time, they laid over 535 miles of a railway line.

At their peak, the firewood companies delivered around 1,500 tonnes of timber per day to the mines and towns. Between 1899 and 1964, some 30 million tons of firewood was cut by the woodlines providing timber to the Golden Mile. As a result, around 2.87 million hectares of the Goldfields Woodlands were clearfelled.

New main woodlines extended into the woodlands where temporary spur lines were laid off the main railway branch to source all the wood in an area. Once the wood was cut, the whole spur would be lifted, shifted to an uncut area, and relaid.

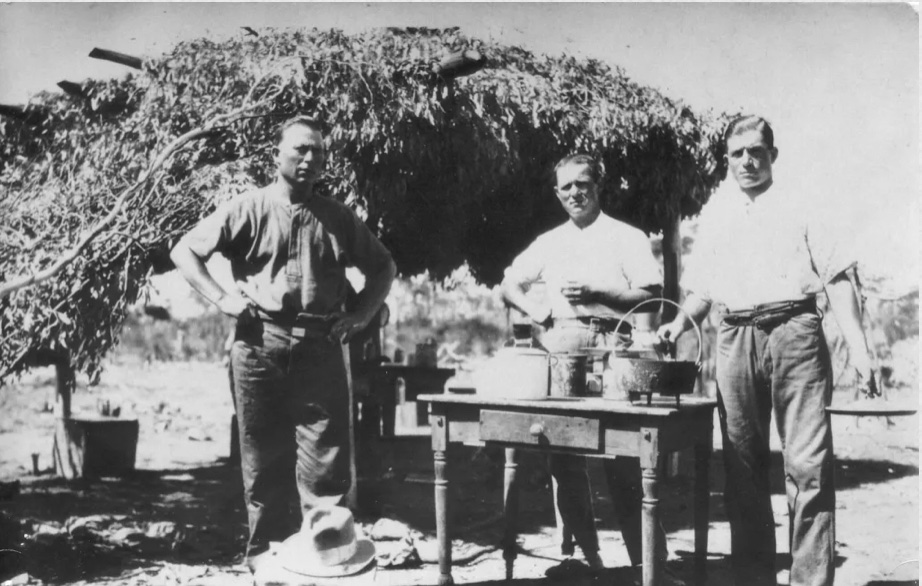

Woodcutters lived and worked in camps at the end of these lines in the most basic conditions. Many were from Italy and the Balkans – Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro – who arrived in Australia to work on the woodlines. They lived in basic camps out in the bush, cutting timber to send to the mine by rail. The camps were very humble and lonely places, situated in isolated locations. They cut firewood that was delivered to the rail line by carters using horses and tipping drays to be stockpiled for manual loading onto rail wagons.

In 1921, WAGFS switched operations to the south of Coolgardie, lifting and relaying 37 miles of permanent woodline. A timber survey estimated supplies over 500 square miles at 5,000 tons per square mile or well over 2,000,000 tons. The main camp was situated about 87 miles from Kurrawang.

By the late 1930s, WAGFS was hauling timber over 170 kilometres from its main camp near Cave Hill. They were running at a loss, and repeated calls to the government to open reserves closer to Kalgoorlie were resisted by the Forests Department. In 1937, WAGFS moved operations east of Kalgoorlie at Lakeside and reopened the Lakewood woodline to the south towards the Eyre Highway, east of Norseman. In these more modern times, trucks became more prominent in the transport of firewood, with over 300 in operation. While installing new power plants at the mines reduced the demand for firewood, and coal was increasingly being used, they were still cutting and supplying 22,000 tons of firewood per month.

During WWII, the Italians working on the woodlines were interned. It created an acute labour shortage, but the production of gold was essential for the nation’s economy. Finally, the government agreed to open mining timber reserves closer to the mines.

In 1942 the firewood industry was declared “protected” by the government to ease the supply crisis. At the end of the war, WAGFS was only servicing one-third of the needs of its customers. Through an underwritten loan from the state government, a consortium of firewood consumers took over the business via the Power Corporation under the name Lakewood Firewood Company. The new company gradually built its business to peak production in 1952, but soon after, the Power Corporation switched first to coal-powered boilers and then to diesel generators, as did the mines. By 1962 the woodline was only producing 9,000 tons a year, mainly for props in underground mines. But that market was also diminishing, with miners leaving rock columns to support stopes. In 1965, the Lakewood Firewood Company ceased operations, and by 1967, the railway line, engines and rolling stock were sold for scrap metal.

Brockway’s legacy

The cutting of firewood started in an unregulated fashion. While Coolgardie was one of the first places in the state to have a Forest Ranger, they were powerless to do more than just keep the peace between firewood cutters. They barely policed the operators and gave no attention to conserving the resource or managing it to ensure sustainability.

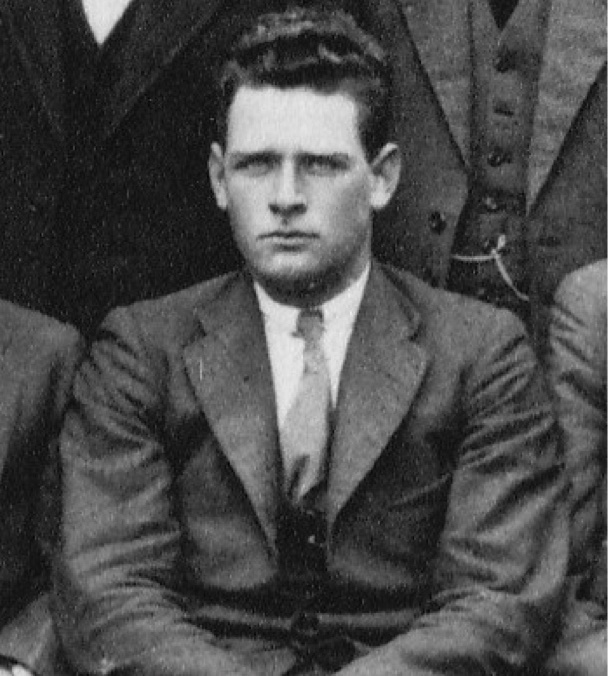

The Forests Act was introduced in 1918, and it formally established a new Forests Department. In 1933, George Brockway, a young forestry graduate from the Adelaide University School of Forestry, was appointed as the officer in charge of the Forest Department’s Goldfields and Wheatbelt regions stationed at Kalgoorlie. He was the first forester to work in these areas.

His main task concerning the firewood cutting was to lay out the cutting areas, make sure good utilisation standards were adopted, and manage the regeneration of the cut-over woodlands. One of his greatest achievements was to regulate the massive and free-for-all firewood industry supplying the gold mines and pumping stations and the regeneration of the woodlands after harvesting.

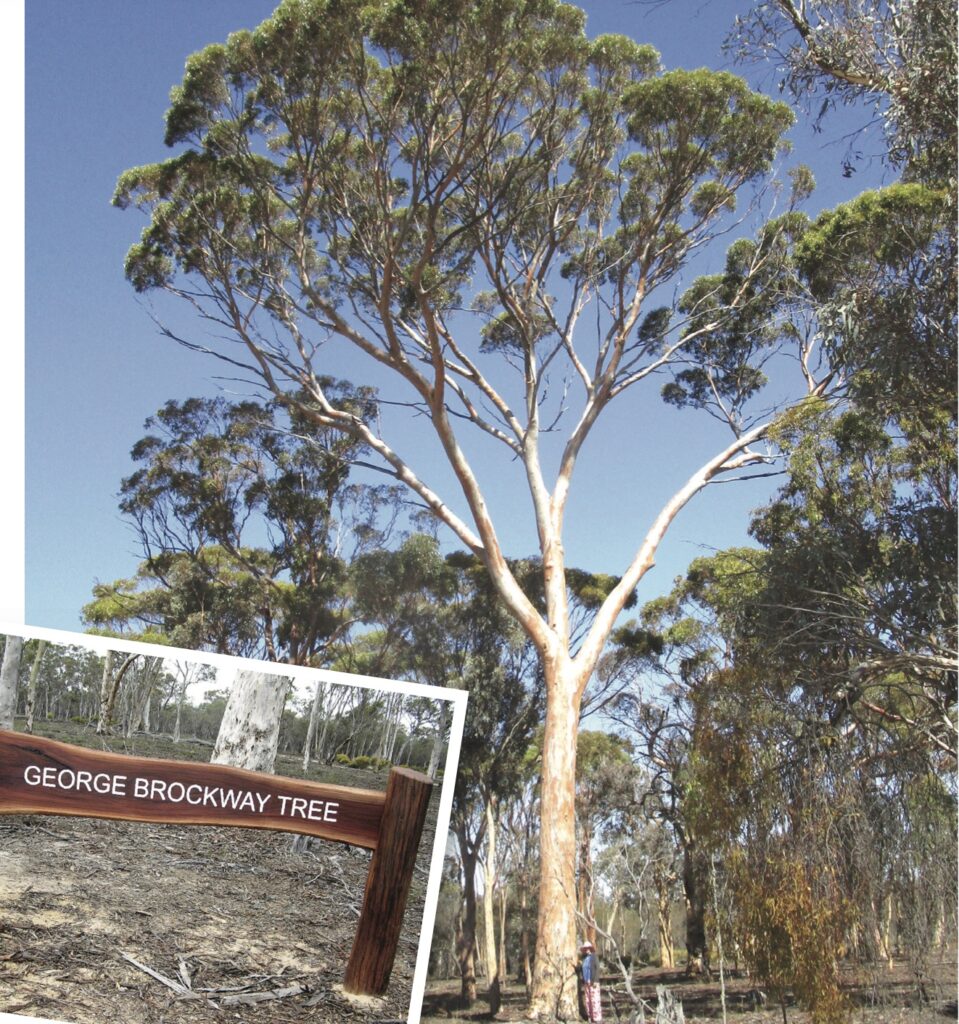

Nearly all the cut-over areas regenerated prolifically. The woodland eucalypts carry large seed crops nearly all the time, making them dependent on disturbance to regenerate. For over 60 years, the former mature and over-mature trees of the Goldfields Woodlands were clearfelled, and the disturbance encouraged prolific regeneration. The magnificent regrowth woodland is admired today for its beauty and conservation values, despite a long history of utilisation that is often forgotten or ignored.

The prolific natural regeneration made Brockway’s task of managing the woodlands easier. So much so that he diverted his energies to the extensive clearing occurring in the Wheatbelt region. He believed too little attention was given to retaining shelterbelts, woodlots, and shade trees. He established a nursery in Kalgoorlie in 1946 designed to propagate the native dryland eucalypts for distribution in the Wheatbelt. It was the first nursery in Australia that focused entirely on raising seedlings of native trees. Many seedlings raised in this nursery now adorn the streets of Kalgoorlie – an inland, dryland city with arguably the finest local native street trees in the world! In addition, he ensured the protection of hundreds of timber reserves scattered throughout the Wheatbelt. Today they are known as nature reserves.

Brockway was undoubtedly a guiding leader in woodland conservation and land management in Western Australia, and he leaves a proud legacy. To ensure that legacy is not forgotten, a little ceremony was held in September 2020 at Yilliminning, where a magnificent salmon gum tree was dedicated as “The George Brockway Tree”.

Fires

A large bushfire that started in December 2019 and continued into 2020 raged through the south-eastern woodland region near Norseman. It burnt over 200,000 hectares. The fire made headlines for the simple reason that the Eyre Highway was closed for twelve days cutting the Nullarbor Plain connection between the Western and South Australian states. What was alarming was the commentary on the fire that emphasised it was “ripping through old growth forests”. The fires impacted both old growth and regrowth woodland and large areas of sandplain vegetation, further highlighting the disconnect between current managers and the land they are supposed to manage. It is also tiresome to read the standard cop-out of blaming these fires on human-induced climate change. Nowhere in the discussion was there any admission of the lack of proper land management.

In recent years, there has been an increase in large, intense wildfires in parts of the Goldfields Woodlands. However, rather than linking climate change with a nebulous concept without any verifiable data, it would be more productive if accountability was taken for what is not happening and active fire and fuel management practices were introduced.

However, it is not as simple as introducing prescribed fires in forests. The wheatfield areas of regrowth are even-aged, carry a different fuel structure and are potentially more flammable than the virgin stands. The focus in preventing fires over broad and variable areas should be on managing the pockets of sandplain kwongan country to prevent big runs of fire spread. This requires strategic planning and a management priority.

Conclusion

From the figures I have supplied above, it is evident that around a third of the Goldfields Woodland was extensively used by the intensive firewood cutting operations. As a result, a vast landscape was denuded of trees over 60 years through one of the most significant industrial uses of timber for fuel anywhere in the world in the twentieth century. But it is a testimony to the resilience of the woodland that 60-120 years later, most travelling through the area would be none the wiser to those historical operations as they witness majestic regrowth trees.

Healthy eucalypt woodland extends as far as the eye can see to Kalgoorlie’s north, south and east. The old woodline cutting areas have regenerated back to their former glory. Only the trained eye of foresters and botanists can recognise the youth of today’s replacement forests. It is reported that trees are more numerous on many sites than before European settlement.

The one area that has changed dramatically is the broad drainage lines or flats to the east of Kalgoorlie. These areas supported a salmon gum woodland, and while it did regenerate, it was severely affected by competition from the long-lived drought-resistant shrubs. These flats now support saltbush and bluebush shrubland. Similar areas of salmon gum woodland to the north of Kalgoorlie that were not subject to similar competition pressure have successfully regenerated back to salmon gum and saltbush woodland.

Sadly, misguided preservation groups and scientific institutions often ignore this history or deliberately portray the woodlands as old growth and intact. They do so to try and push a narrative of a remnant, delicate landscape in dire need of protection and saving, rather than acknowledging the evidence that shows just how resilient the Goldfields Woodlands are. An example of their warped logic is found on the interpretation signs about the Great Western Woodlands. They claim these woodlands are a “refuge for many threatened wildlife species found nowhere else on the planet”. And yet there is no recognition of the vast clear felling of firewood for over 60 years that created this important refuge.

When reading about the history of the goldfields, stories of rich gold finds, deep mines, lucrative profits and booming towns dominate the storylines. However, none of this was possible without timber and, particularly, firewood available to power the mines.

Travelling through the Western Goldfields today, you will see majestic trees. Small, hidden clues remain of the firewood cutting operations. While the concept that we should let nature do its thing has broad appeal, the reality is the purity of the environment has been and will continue to be distorted by human presence. We have no option but to apply active land management principles to sustain these unique ecosystems.

We cannot manage the landscape without acknowledging the past and recognising the resilience of nature and its ability to recover from a massive disturbance. We should not allow ourselves to be drawn into a false “environment is in peril and needs to be saved by doing nothing” mantra. The truth is the Goldfields Woodlands are a truely resilient environment. They should be allowed to continue to thrive under active management, and not wither under benign neglect.

[1] You can read more about George Brockway in Roger Underwood’s book “The Forgotten Conservationist: the story of George Brockway, Western Australian forester and pioneering conservationist” and can be ordered direct from the author via email yorkgum@westnet.com.au

[2] In this section I don’t mention the Mundaring-Kalgoorlie water supply scheme where all the pumps were steam driven up until the 1950s, with boilers driven by timber taken from the Goldfields Woodlands. I touch on the scheme in next month’s Forestry blog. I also provide a more detailed story of the scheme in a Travel blog titled “Liquid Gold” that will be published next week.

If you want to read more about the fascinating history of the Goldfields Woodlines, don’t rely on Google. Instead, there are a number of books on the topic:

Early Woodlines of the Goldfields The untold story of the Woodlines to WW11 by Phil Bianchi

Timber for Gold: Life on the Goldfields Woodlines by Bill Bunbury (Out of Print)

Rails Through the Bush – Timber and Firewood Tramways and Railway Contractors of Western Australia by Adrian Gunzberg and Jeff Austin

Lakewood Woodline 1937 to 1964 : its origins, operations and people by Phil Bianchi

Woodline: Five year with the woodcutters of the Western Australian by Larry Hunter (Out of Print)

Remarkable and intriguing story Robert.

And so true that in today’s woke world where everything is about the evils of humanity trashing the environment rather than if nature’s resilience is understood and land managers work with it, then ecosystems such as these magnificent woodlands are sustainable in perpetuity.

Excellent article.

Once again reinforcing the use of unsubstantiated hyperbole by people/organisations to stifle the application of appropriate management to our forests/woodlands/scrublands.

My father (whose father was an accountant at the Mine) told me stories of his first job working as part of the firewood team (this would have been at the end of WW11).

I regret I never sought more information about this time in his life.

Another very interesting article Robert.

Once again you expose the flaws in the “lock it away is the only way to conserve it” attitude of the self appointed custodians of our environment.

The resilience of our natural environment is obvious to those who genuinely care, but we can’t ignore the fact that our society is inseparably intertwined with it and it is irresponsible to suggest that we should not practice sensitive active management.

I always enjoy reading your articles and the emphasis you place on resilience and management.

The western woodlands were also subject to extensive exploration, basically by clearing hundreds of kms in parallel lines with a dozer so that sampling could occur. I worked on Phytophthora research with F D Podger in 1967 and was then involved in developing and implementing quarantine and hygiene procedures.

Phytophthora spread really took off in mid 1940’s when we had consecutive years of very high rainfall, and again in 1963/64. Jarrah is very susceptible to waterlogging and the combination with Phytophthora was lethal on wet sites.

The climate change hysteria and drought threat have been blown out of proportion. The death of 26 per cent of trees on shallow soil sites over 0.15 per cent of the forest has the IPCC in Geneva declaring the jarrah forest in “imminent threat of collapse”, and with a HIGH degree of certainty!!

Often our time horizon is far too short, especially when dealing with a tree that lives for hundreds of years.

My dad worked in Kurrawang with his dad, who had been there for a while. Dad came to Australia in 1937 and spent two years cutting wood. He was 18. It was hard, hard work. Fresh supplies arrived once a week from Kalgoorlie/Perth. He told us many men didn’t last and would leave after a couple of weeks.

A big reason was the verbal abuse from the English managers. European labourers were treated like second-class citizens, sadly. Dad was thick-skinned and turned a blind eye and lasted 2 years.

I wish I’d listened more to his stories when he was still with us. He passed away 13 years ago, aged 94.