When the Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.) owned and opened up their land grants in north-west Tasmania, the Emu Bay port was crucial in developing the area and the company’s fortunes. In my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, I focussed on the development of the VDL Co.’s estates, principally Surrey Hills. This blog focuses on the development of Emu Bay as a major shipping port on the north-west coast. Despite having natural advantages for a prosperous shipping port, there was only rudimentary infrastructure built by the VDL Co. Significant funding from the government and non-partisan management by the harbour authority, early in the twentieth century, eventually helped create one of the best shipping ports in Tasmania.

There are a number of images of the Emu Bay port during the construction of the second breakwater which I have used in this blog. They are credited to “The Advocate” multimedia, 25 June 2013, and are beautifully presented on a great web site that commemorates the pioneers of Tasmania’s northwest – see them at http://www.tasmanianpioneers.com/blog/perils-of-the-deep

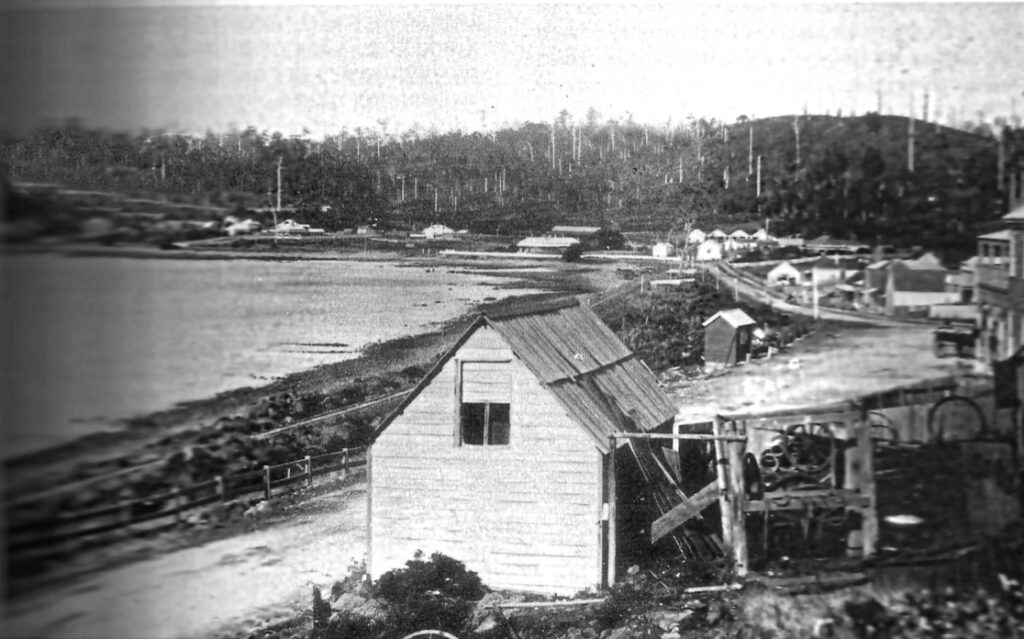

On a small coastal strip in north-west Tasmania, at a location first described as “unfit for habitation”, and as “an entirely wretched, dreary and desolate tract”, was born the town of Burnie. The early settlers eked out a meagre existence splitting palings and shingles and growing barely enough food to sustain their living. The VDL Co. was granted land and sent the first permanent residents on the brig “Caroline” which arrived at Circular Head in January 1828. A month later, they arrived at Emu Bay in a 27-ton cutter, “The Fanny”.

According to Government Assistant Surveyor John Helder Wedge, Emu Bay was one of the few areas on the north-west coast where there was a potential for a deepwater port. Edward Curr, Chief Agent for the VDL Co., instructed Henry Hellyer, in October 1827, to establish an area at Blackmans Point as the supply port for the hinterland farm settlements at Hampshire and Surrey Hills. A few months earlier, Hellyer arrived at the mouth of Whalebone Creek (Oakleigh) and began to mark out a trail inland towards Hampshire. Further inland towards Oakleigh Park, a few slab and bark huts housed VDL Co. employees, including chief surveyor and architect Henry Hellyer and the indentured servants.

Curr believed Emu Bay was more sheltered than Table Bay further to the west. He wanted a wooden jetty built to discharge cargo quickly and safely in moderate weather, with the jetty built “so as to present little surface resistance to the sea but allow the water to wash clear through it with the least possible obstruction”. Almost immediately, Henry Hellyer supervised the construction of a primitive 200 foot log crib jetty at Blackman’s Reef. The VDL Co.’s 1828 Annual Report referred to “a small but substantial wooden pier or jetty”. There was also a store and cottage built from timbers sawn in a sawpit in the forests of the nearby Brooklyn Valley.

The township was carved out of the tall eucalypt forests and ti-tree swamps lining the bay. The first survey of the town was in 1840, and Burnie received its name in honour of William Burnie, the inaugural Governor of the VDL Co., and the only place in the world with this name. The only semblance of any street were the sandy tracks through scrub and fallen trees. It wasn’t until the formation of the first Road Trust in 1859, that any creek was bridged, but even then, they were foot bridges with no access for wheeled vehicles.

Sea trade was necessary for the fledgeling town. From the early days, the shipping facilities were crude. Initially, small sailing ships were beached at Oakleigh to load timber. In 1840, the wooden jetty was extended to 400 feet to provide better protection from the prevailing winds. It was built of massive logs firmly bolted together and filled in with stones. According to Curr, there were six to seven feet of water at low tide and nearly 20 feet at spring tides. Bigger ships anchored in the open roadstead and longboats handled cargo to and from a flat rock at Blackmans Reef on which a crane was erected in 1868, with a swinging basket to hoist passengers ashore. Until the 1880s, heavier loads were hauled up a timbered slope to a level above the waves breaking on the reef.

In 1850, the efficient operation of shipping operations at Emu Bay was still an issue. Burnie was bypassed in favour of other ports on the Inglis and Cam Rivers. VDL Co. Chief Agent James Gibson believed the harbour would benefit from a breakwater or jetty opposite the store. It was crucial for the VDL Co. fortunes after they had decided to sell up and abandon their farming pursuits because of the lack of revenues, and the inadequate port facilities hampered the sales of land in town and the surrounding Emu Bay Estate.

A committee of local identities, however, were the ones that had to push the VDL Co. into some form of action. They managed to raise funds to construct a breakwater pier from Blackmans Point to replace the existing jetty and called on the VDL Co. to contribute monies. The VDL Co. directors felt “quite disposed to promote in every way in their power the success of the project and hope to see it accomplished; being sensible of the immense benefit that would be derived from it”. Despite the rhetoric, the VDL Co. didn’t provide any funds towards the project and it lapsed. Passengers and cargo continued to disembark on a flat area of Blackmans Reef while neighbouring ports prospered.

In 1855, the Emu Bay Crane Company was formed to purchase a one ton crane and they installed it on Table Rock. Using a tripod frame, it proved to be a great asset to shipping at the port. Sadly, the crane was completely damaged during a heavy easterly swell a few years later. John Alexander was a local farmer and he leased a small section of the foreshore just north of Table Rock in 1859 from the VDL Co. to build a wharf. He built a frame for a pig-sty wharf (rectangular wooden structure filled with stones) on the foreshore. Before he could float it into position, a storm damaged the structure and in doing so, took the existing, damaged crane into the sea where it was totally destroyed on the rocks nearby.

After Gibson was given twelve months notice in 1858, the affairs of the VDL Co. were managed by Charles Nichols from Launceston. The VDL Co. by this time was not actively farming and were trying to sell or lease its holdings. Alexander successfully gained another lease from the VDL Co. in January 1862 to build a jetty from the foreshore to Table Rock in front of the VDL Co. store, that was leased by James Munce. Alexander was faced with financial difficulties even though he had been given assurances that he would be reimbursed for his work. However, after being forced to wait over a year from the VDL Co. for any reimbursement he began charging an additional wharfage toll after effectively possessing the wharf facilities, which were not yet fully completed. The local farmers were irate at a new imposition and charge. Alexander relinquished his lease to his son-in-law, Captain John Jones, who revised and increased the wharf charges. He successfully prosecuted anyone that refused to pay his fees. Most settlers sent their produce to Cam River instead to avoid the wharfage fees.

George Woodward was a lighterman before Burnie Harbour possessed good piers. He recalled with pride the Sunday morning in 1868 when a small schooner named the “Sylph” came ashore from her anchorage under a strong south-westerly wind. He managed to rescue a seaman and dog on-board before the “Sylph” broke up. This episode prompted the businesses at Burnie to seek assistance from the Tasmanian Government to construct a pier because trade was being diverted to the Cam River. In 1869 an iron girder jetty was built with a mobile crane that withstood the heaviest easterly gale.

The opening of the tin mines at Mount Bischoff in 1871 significantly increased trade at the port. Chief Agent James Norton Smith pushed for a new jetty. Contracts were issued in 1872 to widen the 12-foot jetty instead of the more significant cost of replacing the old one at the same location. The new set up was sufficient for shipping lighter materials such as grain, tin and palings, via a punt, to boats at anchor. However, the port authority could not handle the greater volume of tin ore and large timber logs.

In 1879, Norton Smith reported that the government accepted a tender for the construction a wharf beyond the current jetty. The difficulties of shipping timber logs proved to be a hindrance in attracting buyers of timbered land at Emu Bay as they couldn’t get the timber to market profitably on the mainland.

In 1880-81, there was talk of building a breakwater or extending the existing jetty 100 metres to improve the Emu Bay small jetty. The jetty was described as a “rickety and jim-crack structure which was erected at considerable expense some years since afforded a moderate amount of accommodation in fine weather, with the wind from the west or south”. The jetty consisted of light cast-iron scaffolding of hollow columns tied together by wrought iron horizontal and diagonal rods. It was poorly exposed to the east, where at high water, the sea covered the jetty. The government employed Charles Napier Bell to design a better operating facility. He recommended the construction of a concrete breakwater extension to the jetty, 650 foot in length and 26 foot wide, using the sloping concrete block system. The cost to do this was prohibitive, and instead the iron jetty was again widened and extended.

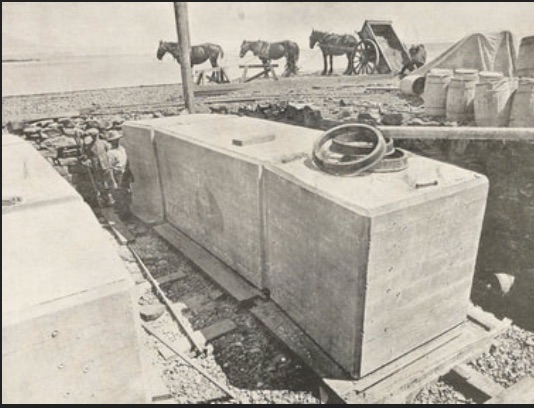

The initial contract work was heavily criticised. It was reported that a considerable amount of coarse stones, dumped into the sea to form the foundation for concrete work, was washed onto the beach and also created a dangerous shoal around the jetty, making it more difficult for boats to approach and passengers and goods to disembark. The Works Department took over construction of the breakwater. The first section of the work extended the current jetty by 40 foot. A large caisson, 40 foot long, 12 foot wide and 12 foot high and partially filled with concrete, was launched and floated to its intended position at the head of the jetty. It was then filled with concrete and stone and sunk to form a foundation. Weighing over 200 tonnes, it was deemed sufficient to withstand the violent storms. Initially, there was no consideration to filling the gaps under the iron jetty between the shore and the jetty’s concrete head. After months of heavy weather in winter, it was decided to build concrete blocks, weighing up to three tons, to stack in these gaps.

At the height of competition with other ports on the north-west coast, there were scurrilous reports from Burnie locals about the ports’ inadequacy and an exaggeration of damages. This criticism increased markedly during the initial upgrade at Emu Bay in 1882. In one case, a newspaper reported that the Emu Bay jetty had been destroyed during strong easterly winds. What happened was that the 200-ton stone and concrete caisson at the head of the jetty had started to disintegrate. Things were not helped when the works took so long to complete and disrupted shipping services. The main legitimate criticism of the jetty was that it did not protect vessels at all time, particularly during heavy easterly winds.

Even after the recent work on the Emu Bay Jetty extension, there was no doubt a substantial amount of work was required to upgrade the port to service the bourgeoning sea trade. In 1885, the government finally agreed to fund Bell’s improvements as long as an equal amount was provided from private sources. Works on the new breakwater pier started in 1886, including the quarrying of the basalt from Blackmans Point. Works were completed in 1889.

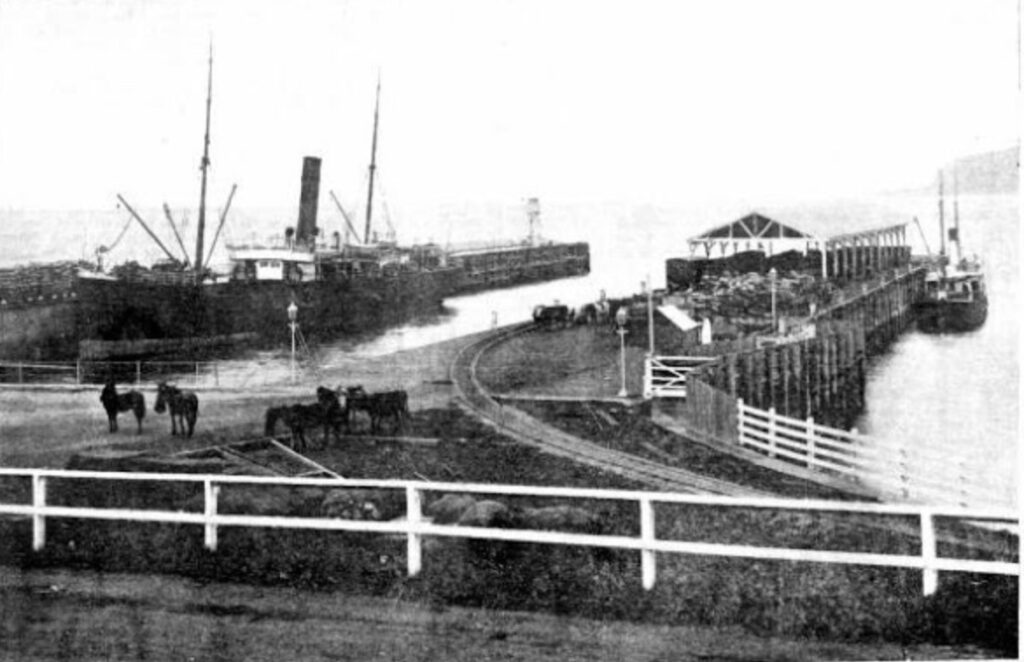

Burnie’s shipping trade was greatly improved, and business advanced at a rapid rate. The Marine Board had to deal with the perpetual problem of accommodating ships. In 1901, a 500-foot long, 60-foot wide, wooden structure was built of turpentine (Syncarpia glomulifera) and Tasmanian hardwoods. It was named the Jones Pier after the late Captain William Jones, a pioneer of the district. Captain Jones was a pioneer sawmiller, hotelier and shipping company owner who also served as the first Harbour Master and was the long-time Warden of the Marine Board. He earned the title “King of Burnie” in recognition of his hard work towards Burnie’s development. Most notably he built Jones’ Hotel (later the Bay View) in 1875 and the mansion “Menai” in 1878.

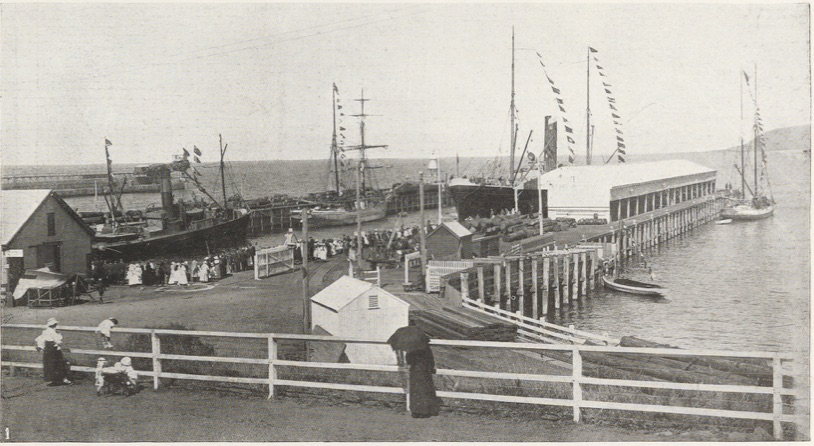

The Marine Boards of Burnie and Table Cape were amalgamated in 1910, and this allowed a greater focus on appropriate shipping facilities for the north-west coast, free of partisan politicking. A year later, the new Board borrowed £120,000 to construct a second breakwater from the extremity of Blackmans Point. Precast concrete blocks, each weighing 60-70 tons, were used. The wall extended in a north-east direction across Emu Bay for 1,250 feet and was completed in 1919 at a total cost of £220,000, aided by government loans. A total area of 10 acres was reclaimed on the outside of the old breakwater. A good summary is provided in The Burnie Advocate. The construction works were aided by the introduction of electric power to Burnie in 1912.

There was a significant increase in the timber trade which coincided with the establishment of a large sawmill in Burnie in 1905, and the formation of the Burnie (Tasmania) Timber and Brick Company Limited in 1908, both by the VDL Co. Chapter 3 of my book “Fires, Farms and Forests” provides a detailed account of the development of the timber trade by the VDL Co. from 1881. To accommodate the increased shipping, a 400-foot wooden pile jetty, known as Emu Pier, was built in the more sheltered waters alongside the breakwater.

After the concrete block breakwater was completed in 1910, a new wharf at 500 feet was built and opened in March 1920. It was called the Ocean Pier. The following year, the wharf was extended by a further 140 foot and was connected to the shore via a concrete viaduct. Divers that were used to help build or repair underwater structures reported undersea wildlife encounters. Joe Hodgson, while repairing the apron of the breakwater, encountered an octopus “which he estimated weighed 1 cwt with 125ft tentacle. He saved himself after a gigantic struggle and repeated thrusts of his 9-inch knife blade” – see page 24 http://www.maritimetas.org/sites/all/files/maritime/maritime_times_issue_58_autumn_2017.pdf

In 1930, the Emu Pier was widened to accommodate passenger and mail ships. It was renamed the McGaw Pier in honour of the VDL Co. Chief Agent and long-time Master Warden at the Marine Board Andrew Kidd McGaw.

The growth of the port in the first half of the twentieth century was greatly enhanced by deep water alongside the piers, which allowed sizeable overseas mail steamers to berth on all tides. This was improved by dredging work which produced a depth of 50 feet at low tide.

Despite a lack of proper funding required to build a wharf and jetty to withstand the vagaries of inclement weather and support the ships brought in transport goods from the Emu Bay port, it continued to operate and eventually improve substantially in the first quarter of the twentieth century. This enabled the VDL Co. to trade out its financial woes and set itself up for the eventual sale of its lands.

The fortunes of the VDL Co. were indeed tied to the successful operation of the Emu Bay port.

Good read Robert. Where can I get a copy of your book?

Cheers Mick Rawlings

Mick try the local bookstore in Burnie “Not Just Books”. They had copies and they can order in more if they are out of stock. Alternatively, you can buy direct from the publisher via my home page on the website.

Cheers

Robert

What a great article.

My grandfather’s sister and her husband, a master mariner, had the hotel at the Cam in 1881. I can see now why it looked to be a better investment than it turned out to be. Burnie was beginning to win the battle of the wharves.

My grandfather came to Burnie from Waratah and worked on the breakwater. He then worked on the wharf all his life as did my father.

As usual Robert a very interesting read.

Very good read, thanks.

Great article Robert. Thank you.

Dear Robert,

I’m pleased to hear from you so promptly.

I belong to the Blackwells of Blackwell Road Oonah, and writing a book on Tarkine Myths, listing all the mining of the North West, also the subsidiary roads of Blackwells Road, the chalet, etc. I wondered how much you knew of Wiff Campbell’s involvement, when he introduced Mack trucks and anything else of road development. How big is the quarry on Quarry Road? Do you have a digital map of the subsidiary Roads in Blackwells Road? (I have a list of about 30)

Cheers

Rex Blackwell