“The only fence in the world that cuts a continent into two mighty paddocks”. Ernestine Hill

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, rabbits began eating their way towards Western Australia. They were known as a serious threat to the environment and ruined profitable farming land in the eastern states. They were difficult to control which required labour-intensive work. As rabbits began to be noted in new locations and in greater densities, their movement came to be characterised as “the advancing menace” and “the grey invasion”. The Inter-Colonial Rabbit Commission offered a £25,000 reward to anyone who could demonstrate a new and effective way of exterminating rabbits. There were reports of rabbits in neighbouring South Australia and soon after it was reported that they had crossed the Nullarbor Plain in 1894. The Western Australian government, however, responded rather slowly to the oncoming threat.

In 1896, they instructed surveyor Arthur Mason to lead a group from Coolgardie eastwards to the border to study the likely incursion of rabbits into Western Australia. He reported that “rabbits are travelling and at the rate they are moving will soon overrun the southern portions [of the state]”. Accordingly, he recommended that a barrier fence be erected to stop the rabbits from entering Western Australia. He optimistically speculated that “it would not take long with the assistance of boundary riders, poison, cats etc., to eradicate the pest”.

Five years later, a Royal Commission was held to inquire into the rabbit question in Western Australia. Its report in 1901 recommended the construction of fencing at once.

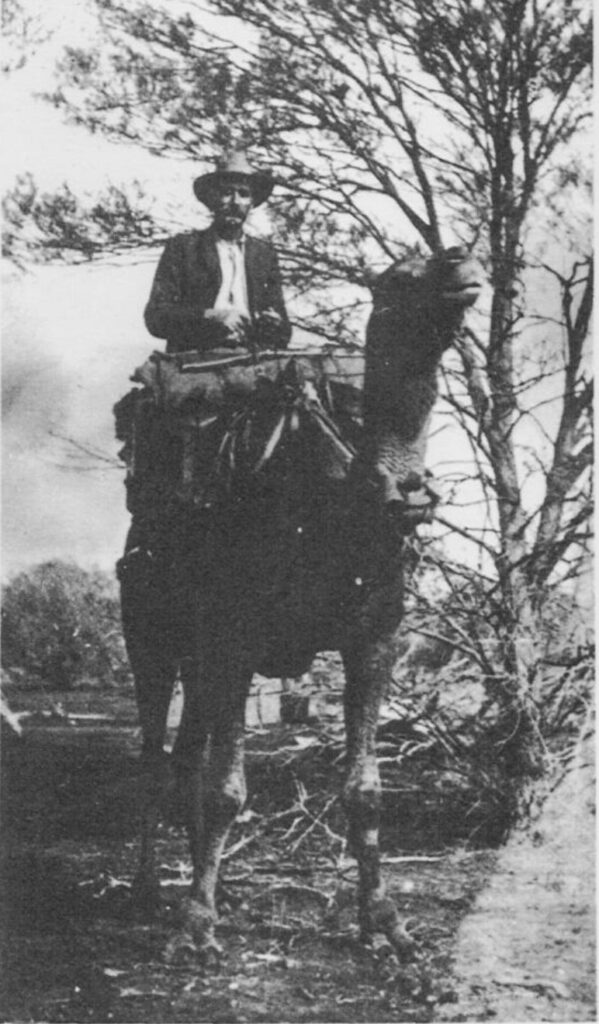

In September that year, surveyor Alfred Canning was commissioned to survey the location of a fence to cut off the invading rabbits. He was tasked with assessing the unfamiliar landscape, the availability of timber, the stability of the ground to hold fence posts, and the accessibility of water and feed for animals during construction. Canning took three years to complete his exploratory survey with Hubert Trotman, Afghan cameleer Hassan, and eight camels. It was a tough job. The survey party navigated their way through remote, challenging and often unmapped territory, dealing with heat and unknown water sources. It was fortunate that Canning was a meticulous man with a marvellous sense of direction and unwavering fortitude.

Still dragging its feet a few years later, the Western Australian government was forced to start a fence to protect the agricultural areas in the state.

Building the fence was an ambitious, arduous and slow undertaking. Construction started in late 1901 and was initially carried out by private contractors working in stages and section by section. Delays were common. In 1904, the responsibility for the completion of the fence shifted to the Department of Public Works, under the supervision of Richard Anketell, a surveyor and builder of the Western Australian railways and the Kalgoorlie pipeline. He had 120 men employed in gangs, 350 camels, 210 horses and 41 donkeys.

The starting point was Burracoppin, about 300 kilometres east of Perth, working north to Point Kerauden on Ninety Mile Beach (north-east of Port Hedland) and south to Starvation Bay, west of Esperance. Posts were of whatever local timber was available, or iron standards were used where timber was unavailable. Mulga (Acacia aneura) was mainly used for posts but for example, the Ravensthorpe section used saltwater paperbarks (Melelaleuca cuticularis). Near Hyden, they used the hard-wearing jam tree (Acacia acuminata).

The posts were set 12 feet (3.6 metres) apart with strainers every five chains (100.5 metres). The wooden posts were no less than four inches (10 cm) in diameter and stood four feet (1.2 metres) above the ground, and sunk about one foot nine inches (54 cm) below the ground. There were three 12.5 gauge plain wires at 4-12-36 inches (10-30-90 cms) above the ground. They were threaded through holes bored into the posts. A fourth barbed wire followed by another plain, then another barbed wire was added to make the fence dingo and fox proof. Finally, wire netting was fastened three feet (90 cm) above and six inches (15 cm) below to prevent rabbits from burrowing under the fence. This portion was dipped in coal tar first.

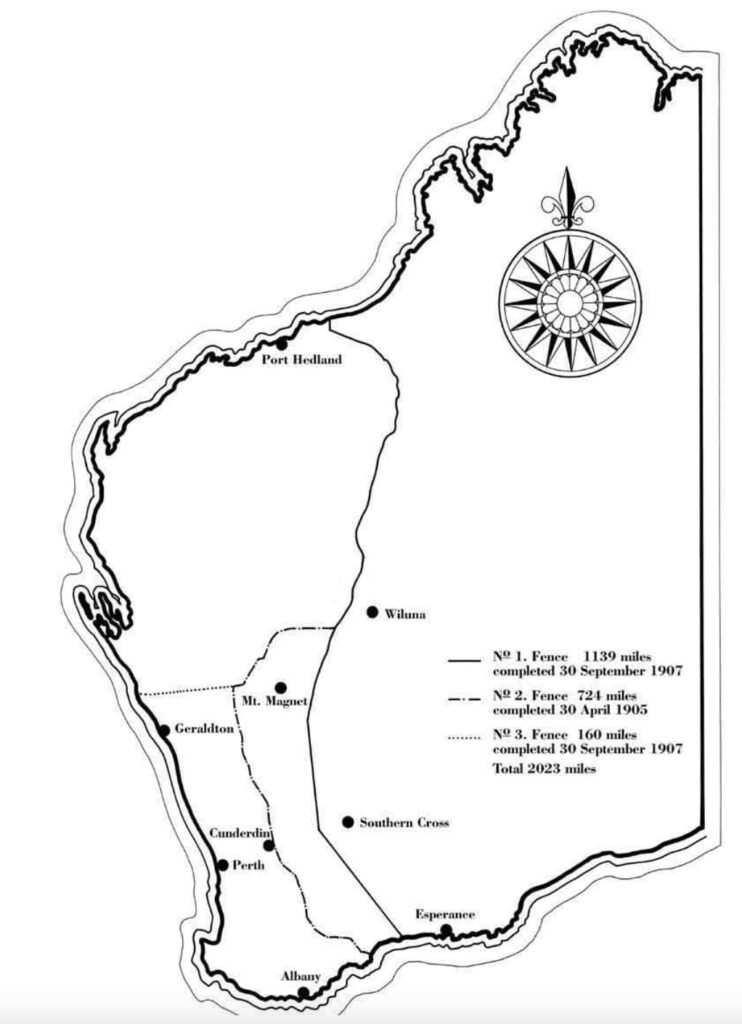

The whole project was completed in 1907. It ran through some of the most inhospitable terrain of the continent. There were three fences. Before the original No. 1 fence was completed, rabbits were hopping into regions the fence was intended to protect. They were sighted near Cordingup Gap, about eight kilometres east of Ravensthorpe, in December 1904. The No. 2 fence was built in 1906 and ran from Point Ann on the southern coastline, west of and roughly parallel to fence No. 1, which it joined at Gum Creek. It was 1,165 kilometres long and was completed in 1905. The No. 3 fence, completed in 1907, ran a short distance of 257 kilometres west from its junction with the No. 2 fence near Yalgoo to meet the coast north of Geraldton.

All three fences stretched a combined distance of 3,256 kilometres. According to former boundary rider and historian Frank Broomhall, the No. 1 fence, at 1,833 kilometres, was “the longest line of unbroken fence in the world” when it was completed and could be seen from space. However, the construction cost was enormous at £167 per mile ($250 per kilometre) and controversial.

The living conditions for the labourers were harsh. They worked in the outback with little or no contact with the outside world and depended on teams of camels travelling 10-12 miles per day. The constant presence of flies, heat in summer, biting easterly winds and frosts in winter tested their resolve.

The regime of maintaining the fences was extensive and costly. Wind storms, sand drifts, flash floods, bush fires, insects and animals (termites, wombats, kangaroos) regularly caused damage and created breaches in the barrier. Also, the provision for gates created a weakness to the integrity of the fence system. The fence was maintained by boundary riders who patrolled 240 kilometres stretches alone with camels, horses and carts, and later even bicycles. Their work was crucial in repairing breaks in the fence. The isolation and the silence in the vast landscape must have been very eerie.

The rabbits bred and multiplied rapidly, and although the fence proved a worthwhile barrier, that ended in 1927 when large numbers of rabbits hit the rabbit-proof fence north of Murchison. By the 1930s, they had spread all over the agricultural areas inside the fence, driving farmers off their land because the rabbits had eaten the crops and the pastures they had planted.

Due to WWI enlistments and the difficulty obtaining materials, the government seriously considered abandoning the No. 1 fence. However, this was avoided, and by 1920 the first motor vehicles were used to monitor the fence. Grids and rabbit proof gates were constructed where the fence crossed roads. From the 1940s, the riders began using machinery to help them patrol their sections. They designed and built ingenious permanent water holes and huts at regular intervals of about 48 kilometres, gates every 32 kilometres and trap yards for foxes and dingoes as well as rabbits every 16 kilometres.

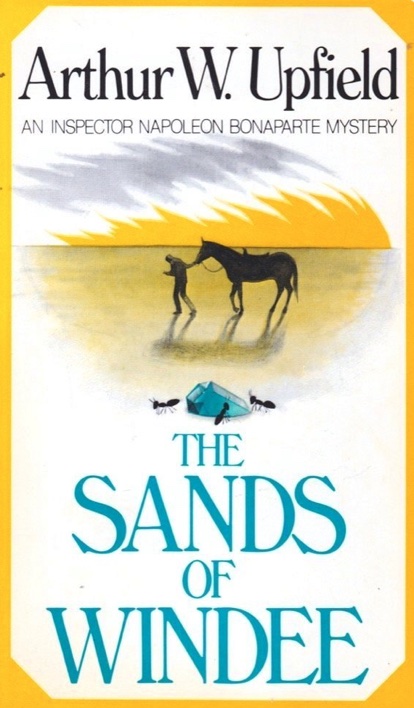

The No. 1 fence has had a colourful history. Former fence rider and renowned Australian author Arthur Upfield wrote a novel of murders in the desert called “The Sands of Windee”. The plot of his book was based on committing the “perfect” murder. Upton discussed his ideas with fellow boundary riders. He based the story of his novel on getting rid of the bodies by burning and crushing the bones in a dolly pot. One of his colleagues was John “Snowy” Rowles. He used Upfield’s ideas to commit three murders and dispose of the bodies whilst working in the area. George Lloyd and James Ryan disappeared from a fencing camp a short distance from the Camel Camp. They were last seen near the Challi out camp on 9 December 1929, and it was initially thought they had moved away to another job.

Not long after, in the New Year, Louis Carron left Fountain out camp with Rowles and was never seen again. His disappearance was reported to the police, and his burnt remains were found in a campfire at the 183-mile gate. Upton’s book was published around the time of the murders and was hugely controversial. Rowles was convicted of the murders after a trial and hanged in Fremantle goal in 1931. A two-part series on the ABC called “Blood in the Sand” is based on the story of these murders.

The fence was also a guide for the two Craig sisters, Molly (14 years) and Daisy (8 years) and their cousin Gracie (10 years). They absconded from the Moore River Aboriginal settlement and followed the No.2 fence north until Gracie tried to catch a train. Molly and Daisy continued until they came across the No.1 fence, which they followed north back to their home at Jigalong. The amazing journey took nine weeks and covered about 1,200 kilometres. Their journey is featured in the book “Follow the Rabbit-proof fence” by Doris Pilkington (1996) and the film “Rabbit Proof Fence” directed by Philip Noyce (2002).

Since the decline of the rabbit population in 1950, due to the impact of poisoning and myxomatosis, the No. 1 Fence has been linked up with the former No. 2 and No. 3 fence. The Murchison Regional Vermin Council was established in 1963 to rehabilitate and maintain the old No. 1 fence, now referred to as the Vermin Fence or State Barrier Fence. It was also known as the Emu Fence. The Council rangers look after the fence from the 80-mile peg in the south near Lake Moore to the 426-mile peg in the north near Neds Creek.

There is an extraordinary periodic history involving emus and the rabbit-proof fence. It first started in 1932, following a long hot summer and drought conditions. This sparked a migration rampage of wild emus from the pastoral region in the Murchison district to the farming areas. They were drawn to the fence to seek food from crops and pastures on the other side. Farmers feared for their crops. In a bid to stop the advancing emus overwhelming the rabbit-proof fence, farmers enlisted the help of the army. Major Meredith of the Royal Australian Artillery led a party that were armed with Lewis machine guns and 10,000 rounds to try and quell an estimated 20,000 emus. However, they spectacularly lost the “Emu War” against the defenceless and flightless birds!

The problem was that there was so much food available for the emus they were gathered in small groups. The first attempt by Meredith’s men was to use beaters to herd the small groups into firing range. At a distance of about one kilometre, the first burst of fire landed short, with the second burst killing only a small number as the emus raced for the cover of the nearby trees. The army decided to change tactics and resorted to ambush. Guns were set up at a dam, and close to sunset, a hundred emus approached the dam within 100 metres. The gunners opened fire only to see the emus scatter and disperse. The next day a flock of about 1,000 emus headed for the water in the dam. Again, the emus scattered after the machine guns opened fire, aided by the jamming of one of the guns. The army and farmers were amazed at the emus’ ability to sustain injury and keep running. Major Meredith was quoted as saying, “if we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world. They could face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks. They are like Zulus…”

Less than a week later, the Defence Minister ordered an embarrassing withdrawal of the troops after their unsuccessful mission. The Prime Minister, Joe Lyons, told Parliament the Defence Department would not pay the bill for hunting emus with machine guns. This prompted a question from the floor, “Is a medal to be struck for this war”?

In 1976, another similar emu event occurred where it was reported more than 100,000 emus came south searching for food and water and were concentrated against the rabbit-proof fence.

The three fences have been modified and realigned into one fence. Close to the south coast and in the north of the State, it has fallen into a state of disrepair. Today, the fence is much shorter, running from the Zuytdorp Cliffs near Kalbarri to Jerdacuttup in the Ravensthorpe area, where abutting farmers and graziers use it as a boundary fence. In 1964, it was decided to maintain the fence from intermittent invasions of dingoes/dogs from the northern regions. Today, it is mainly used as a barrier to aid in managing migratory emus from pastoral lands into agricultural land.

The fence went through many transformations in its lifetime, reducing the encroachment of rabbits, wild dogs, emus, kangaroos and other feral animals. Global events such as WWI and the 1930s Depression limited the availability of men and materials, which threatened the viability of the fence to act as an effective barrier.

However, it remains a significant cultural legacy and I leave the final words to The West Australian journalist A. D. Boulger who wrote:

“…the rabbit-proof fence, the work itself, at least, stands as a monument of what human ingenuity and perseverance can accomplish in the face of many and great difficulties”.

As an aside, Alfred Canning, the surveyor of the fences, is better known these days for a project he did not long after the rabbit fences’ surveys. He surveyed the 1,800 km long stock route from Halls Creek in the Kimberleys to Wiluna in the mid-west and about 550 km north of Kalgoorlie. The Canning Stock Route is a popular challenge for 4WD expeditioners these days.