Introduction

In September 2021, the Premier of Western Australia, Mark McGowan, made a shock announcement that all native forest logging would cease in 2024, at the end of the current 10-year Forest Management Plan. The decision was made without consultation with the timber industry, public, or government agencies. The reasons for the decision were to save the forests and preserve the carbon stocks. And yet, despite the fact strip mining for bauxite completely removes the forest and its carbon stocks, as well as the soil that the forest grows in, mining for bauxite will continue.

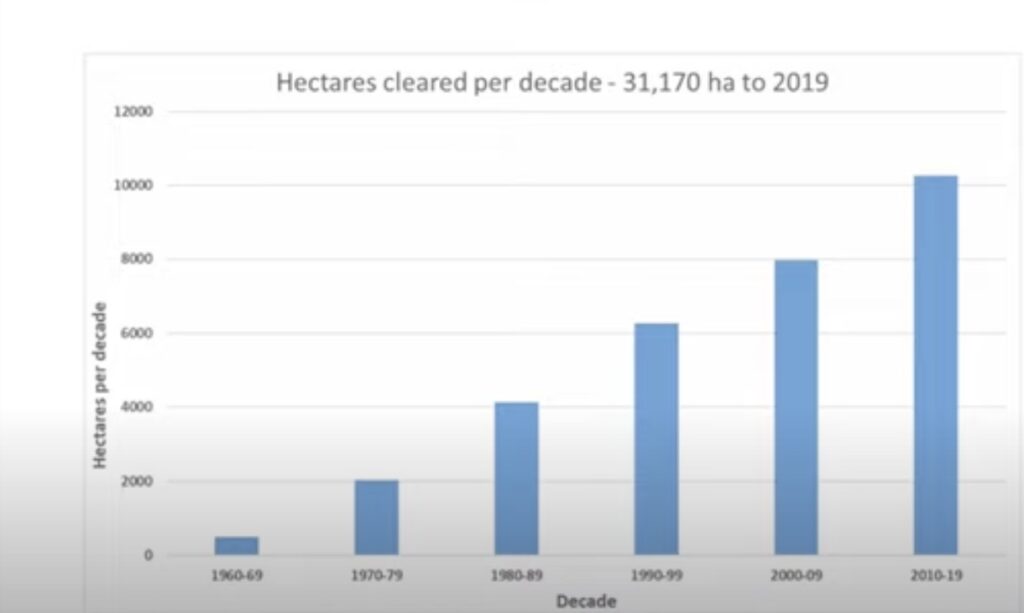

Bauxite mining started in Western Australia near the historic sawmilling town of Jarrahdale in 1963. Agreements were signed by the government and continue to be honoured by subsequent governments. The size and rate of mining were initially estimated to be around 30 acres or 12 hectares per year.

In 1961 when the Alumina Refinery Agreement Act 1961 was first debated in Parliament, the few politicians that questioned the wisdom of allowing bauxite mining in state forest were assured that the area to be mined would not exceed 12 hectares per year. The Minister for Industrial Development, Charles Court (later to be Premier from 1974-82), had this to say in Parliament:

“It is anticipated that the total clearing for the first year would be in the order of 30 acres; and for subsequent years, and so long as the company was on an output of 550,000 tons per annum, 25 acres. I stress these acreages because I think it has been conveyed in the public mind that huge areas will be involved all the time, and we will have ugly scars all over the place from one end of the State to the other”.

However, during the first decade of operations, a total of 490 hectares was cleared for bauxite mining. The Forests Department expressed concern about the mining expansion in the jarrah forests in its 1970 Annual Report:

“The current level of mining activity in forests areas is of major concern. The over-riding powers of the Mining Act in respect of State Forests and timber reserves which date from the early days of gold mining coupled with the marked increase of mining activity, has given rise to the greatest threat the forest estate has experienced”.

The government ignored these concerns as clearing for bauxite reached 2,040 hectares in the 1970s. It represented a five-fold annual increase in production after Alcoa’s second refinery was constructed at Pinjarra in 1972. In a short span of only 15 years, the area of state forest cleared annually for bauxite mining had grown from 12 to 200 hectares per year.

Up until the mid-1970s, the two refineries were serviced by three mine sites near Pinjarra and Jarrahdale. This soon changed after new legislation in 1976 and 1977 allowed the expansion of bauxite mining with new refineries at Wagerup and Worsley. The Wagerup refinery on its own doubled bauxite production and forest clearing rates. This continued expansion of the bauxite industry in Western Australia led to a report by the Western Australian Division of the Institute of Foresters of Australia (IFA) in 1980. The IFA recommended an upper limit on the forest areas to be cleared and mined and called for the exclusion of healthy jarrah forests from mining operations.

Again these concerns were ignored. In the decade to 2019, 10,260 hectares were cleared for bauxite mining, giving a total of 31,170 hectares, a far cry from what was envisaged initially to ensure there were no ugly scars from one end of the jarrah forests to the other.

The 10-year Forest Management Plan is a comprehensive policy document that governs the forest management activities within the public forests in the south-west. It includes recommendations for conservation reserves, the amount of timber that can be harvested each year, and the conditions under which it is done. It is finalised after extensive public consultation.

Yet despite the early concerns of the Forests Department and the IFA, leases under the State Agreement Act 1961 allow strip mining of bauxite over 47 per cent of the public forests in the south-west of the state outside the auspices of the Forest Management Plan, and thus operate with little public scrutiny or input. Moreover, the comprehensive Forest Management Plan has no control or influence over the mining activities that are allowed to continue under the government’s new policy.

The Western Australian Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) approves mining expansion proposals. In May 1995, the EPA assessed the expansion of production at the Wagerup Refinery to 3.3 million tonnes per year and associated bauxite mining by Alcoa. The EPA made it clear “the purpose of this assessment is to consider the environmental acceptability of the proposed expansion, rather than reconsider whether the existing approved operation is environmentally acceptable”. They claimed the expansion did not increase the mining area, “rather it increases the rate of mining within approved areas”.

In a further EPA report in November 2020, to assess the increase production at the Wagerup Refinery to 4.7 million tonnes per year and associated increases in bauxite mining, there was no mention at all of the forest areas to be cleared, nor the impacts on the forest. The EPA did not consider water “as a key environmental factor for the revised proposal”. Alcoa certainly did, as they had to thin the rehabilitated regrowth in the catchment twice to maintain sufficient water supply for their own operations.

The EPA has a very narrow scope when assessing the environmental impacts of bauxite mining. They simply evaluate whether the vegetation type affected is already represented in reserves. They do not regard expansion as an increase in the mining area since the whole mining lease is already approved. They don’t consider cumulative impacts, nor do they consider water values. In contrast, in the last Forest Management Plan there was a significant focus and debate about soil compaction associated with machinery used in timber operations.

Whereas native forest harvesting operations are under constant scrutiny and continually wound back due to excessive environmental controls, bauxite mining can expand significantly with little environmental scrutiny. As a result, the best and healthiest jarrah forests are targeted without any recompense.

Premier Mark McGowan ignores these contradictions and offers a benign environmental justification to end logging in native forests. But at the same time, his government oversees ongoing clearing and rehabilitation operations in the prime jarrah forests north of Collie with less environmental scrutiny.

What is bauxite, and why is it mined?

Aluminium is the third most abundant resource on Earth in its raw form. The soft, red, mineral-laden rock called bauxite is a raw material used in the commercial production of alumina (aluminium oxide) to create aluminium metal. It is usually strip mined because it is almost always found near the surface, with little or no overburden.

Bauxite is not a mineral. Instead, it is a rock composed of impure aluminium-bearing minerals. It forms when laterite soils are severely leached of silica and other soluble materials in wet tropical and sub-tropical climates.

The first step in producing aluminium is to crush the bauxite and purify it using the Bayer Process. Next, the bauxite is washed in a boiling sodium hydroxide solution, which leaches the alumina from the bauxite. The alumina is then smelted by electrolytic reduction or the introduction of a very intense electrical current in a molten bath of natural or synthetic cryolite using the Hall-Heroult process. The liquified aluminium can then be extracted, cleaned, and poured into solid ingots. Electrolysis is used instead of carbon reduction because the required temperature is too high for economical extraction.

Transforming bauxite into aluminium is very energy intensive. That is why power plants are built solely to support the aluminium industry. Pure aluminium is very stable, and thus an extraordinary amount of electricity is required to fashion a final product.

Aluminium is favoured because it has a low density, is strong when alloyed, is a good conductor of electricity, and resists corrosion.

There are many standard products made with aluminium that we use every day and take for granted such as laundry detergent, cement, aspirin, roofing, soft drink cans, spark plugs, foil containers, foil wrap, makeup, appliances, fluorescent light bulbs, dishwashers, cookware coatings, chemicals, deodorant, polishing compounds, toothpaste, and all forms of vehicles.

Australia is the largest producer of bauxite, representing about 28 per cent of global production. Australia’s largest bauxite deposits are found at Weipa in Queensland and Gove in the Northern Territory. Those two are some of the highest-grade deposits found globally, achieving 49 and 53 per cent alumina respectively. Other significant deposits are located in the Darling Range in Western Australia, which has the lowest grade bauxite ore mined commercially, at around 27-30 per cent alumina.

There are seven alumina refineries in Australia, with four in Western Australia at Kwinana, Pinjarra, Wagerup, and Worsley. More than 80 per cent of alumina and aluminium production is exported for the transport, packaging, building and construction industries.

There are four primary aluminium smelters in Australia at Bell Bay in Tasmania, Boyne Island in Queensland, Tomago in New South Wales, and Portland in Victoria.

There is no doubt the mining of bauxite is an important resource to produce aluminium products, essential for so much of today’s societal needs. The question is, does it have a much lower environmental footprint in Western Australia that justifies its unfettered continuation compared to the cessation of sustainable harvesting of native forests due to environmental reasons?

A history of bauxite mining in Western Australia

In 1957, one of Australia’s most successful mining companies, WMC Limited, began exploring bauxite in Western Australia’s Darling Range. Within a year, sound deposits had been delineated. Encouraging results prompted WMC to invite two other Australian mining companies, Broken Hill South Limited and North Broken Hill Limited, to join the venture. As a result, a new company, Western Aluminium NL, was formed to develop an integrated aluminium industry.

The undertaking, however, needed enormous capital input and a background in technology not available in Australia at the time. The then Aluminium Company of America was approached, with the Australian companies offering a partnership in exchange for the necessary capital and technology support. Alcoa of Australia was formed in June 1961 and was granted a 1.26 million hectare bauxite mining lease by the Western Australian Government under the State Agreement Act 1961. In 1994, the lease was amended to cover only the bauxite resource, reducing the area to 712,900 hectares.

In July 1963, the Jarrahdale Bauxite mine opened, and Alcoa commenced operations in the jarrah forest, at around 12 hectares a year. The mine operated until 1999. Alcoa currently operates two mines. Huntly began operations in 1976 and Willowdale in 1984. The Jarrahdale mined was classed as fully rehabilitated in 2001. Alcoa’s current bauxite mining operations are encroaching high ground around the slopes of Mount Solus, a popular area for bushwalkers.

A second company, Worsley Alumina Pty Ltd (now owned by BHP subsidiary South 32), began mining bauxite on its lease adjoining Alcoa’s in the northern jarrah forests in 1974. Its Mt Saddleback-Marradong bauxite mining operations have expanded northwards toward Bannister Hill.

Clearing of jarrah forest is required to mine bauxite. Therefore, mine rehabilitation works have been a primary focus. In the early days, rehabilitation focused on establishing plantations of pine and eucalypt species instead of native jarrah. This was because of the threat of dieback killing the jarrah trees. Since the 1970s, Alcoa has committed to improving its rehabilitation work. After analysing a series of field monitoring plots, they decided in 1989 to use only jarrah and marri trees in the rehabilitation works. In the last 15 years, a key objective of the rehabilitation program has been a focus on the full suite of plant species that make up the jarrah forests using some innovative seed collection, plant propagation and soil cultivation techniques.

Today, nearly 1,000 hectares of jarrah forest is strip-mined each year. Bauxite leases cover the prime jarrah forests north of Collie and almost all of Perth’s water supply catchments.

The government has approved the expansion of mining to two million tonnes of un-refined bauxite for direct export. The genesis for this began in 2014 after the Indonesian government banned the export of unprocessed minerals, squeezing the world’s supply of bauxite into the market. It meant that the Chinese alumina refineries had to look elsewhere for bauxite, and the bauxite price rose. This saw changes in the Australian bauxite industry, with Rio Tinto closing the Gove refinery and switching that business into a simple dig-and-deliver exporter of bauxite. What followed was the start of unprocessed bauxite exports from south-west WA. While the bauxite price remains high, shipping unprocessed Darling Range material is an economic proposition.

Therefore, with no value-adding refining into alumina, it is now questionable what benefit is provided to West Australians from this practice apart from the export earnings of raw material.

Ineffective protests against bauxite mining

In the 1970s, conservationists led an ultimately unsuccessful campaign against Alcoa’s significant expansion of bauxite mining. The Campaign to Save Native Forests (CSNF) was primarily set up to oppose woodchipping operations. They broadened their campaign against bauxite mining impacts when Dr Syd Shea, a senior employee of the Forests Department and the future executive director of the Department of Conservation and Land Management, outlined the ecological damage to forests from bauxite mining was much more damaging than woodchipping operations.

CSNF produced a four-page broadsheet that warned of “an impending threat to Western Australia’s water supply” through increased salinity. Before legislation allowing the new bauxite mines at Wangerup and Worsley, CSNF began a campaign opposing mining expansion. They even held a “salt assault” by placing salt on the steps of Parliament. The inadequacy of the environmental protections associated with this expansion was based on data provided by the mining companies without any scrutiny associated with an Environmental Impact Statement process. The bauxite mining process started in the 1960s as a limited venture covering only 30 acres of forest annually. It changed dramatically without any public input, which meant that Alcoa needed more independent scrutiny of its operations.

CSNF held “non-violent” disobedience protests in 1978, culminating in a “Darling Range Parade” where various environmental groups marched with placards calling for a public enquiry into bauxite mining. Protests escalated with the occupation of Alcoa’s Wagerup refinery site in February 1979 (that was subject to an Environmental Impact Statement process), which stopped operations over a weekend. Protesters were arrested, and new legislation was introduced to make protesters who hindered or obstructed activities liable to fines or twelve months’ imprisonment.

After brutal political attacks against the protesters by politicians backed by favourable media coverage, the protests against bauxite mining fizzled out. They realised they were against very substantial, sophisticated and powerful investment interests. Instead, the environmentalists went after an easier target and spent the next 20 years in a concerted effort to halt logging in “old growth” forests, create more national parks, and eventually force the cessation of logging in all forests. While they have been successful on those fronts, they don’t exhibit the same level of zeal in opposing the continued expansion of bauxite mining in state forests.

Only recently, forest activists demonstrated their perverse focus on native forest harvesting while totally ignoring bauxite mining in the jarrah forests nearby. For example, in late February this year, the Jarrahdale Forest Protectors Group opposed plans by the Forest Products Commission to log jarrah forest near the Serpentine Dam claiming they will “chop down mature jarrah trees which are some of the last remaining in our state”. Yet right next door, they choose to ignore the wholesale clearing of mature jarrah trees for more bauxite mining which will continue for another 40 years at least, even though the much more benign selective logging operations will cease in two years.

Putting the impacts of bauxite mining on the jarrah forest into perspective

Mining starts by clearing all vegetation, salvaging any timber, and burning the debris. Next, topsoil is removed and stockpiled. Finally, up to five metres of soil containing bauxite is removed. Jarrah trees grow in this part of the soil.

Purely on a numbers basis, it appears the impact of bauxite mining on the jarrah forest estate is relatively minor after continuous operations for the last 59 years. Official figures up to 2019 show that 31,170 hectares have been cleared, which represents about 4.4 per cent of the northern jarrah forest type.

Foresters argue that a lot more forest has been affected. According to retired forester Jack Bradshaw, 90,000 hectares of the best jarrah forest has been mined or is fragmented by mining to the present time. This is because the total area affected by mining is three times the amount that is cleared and strip-mined. A visual impression of the extent of mining is provided in this YouTube video produced by Jack in December last year.

The graph below shows that bauxite mining in the jarrah forests continues to increase every year, and further expansion is proposed.

Much of the jarrah forests and wandoo woodlands of the northern Darling Range are destined to be eventually strip-mined for bauxite or aluminium ore. The bauxite ore is recovered from below the thin, laterite caprock covering most hilltops and low ridges. The mature forest and laterite “pods” are removed during mining, often with their fringing “breakaway” landscape, before the area is rehabilitated with young replacement forests.

Mining will continue for at least another 44 years to 2066 under Alcoa’s lease terms and probably for as long as the low-grade ore remains profitable to mine. It is abundantly clear that by granting mining leases for such an extended period, the State has little bargaining power.

While the legal framework can control the rate of mining, and hence the rate of forest clearing, it does not control where and when mining and clearing takes place within the Mining Leases. The bauxite companies must provide six months’ notice of their intention to enter state forest to cut and remove forest products and overburden, but it cannot be stopped in any way.

In contrast to the clearing of nearly 1,000 hectares of jarrah forest each year, around 6,000 hectares (0.8 per cent of the jarrah forest available for harvesting) are currently harvested to achieve the sustainable yield of first-class sawlogs. So why is it that the sustainable harvesting of native forests on that relatively small scale which does not entail any clearing, is seen as bad for the environment when unfettered clearing of prime jarrah forests is allowed to continue?

A report prepared in 2017 for a Commonwealth Senate inquiry into the rehabilitation of mining projects outlined a history of reserves in the Alcoa lease area. It included 22,000 hectares of high conservation value areas in the northern jarrah forest under the RFA process in the late 1990s. However, the reserves were not gazetted until much later in 2001 because the government had to negotiate with Alcoa where the reserves could be located. As a result, Alcoa maintained access to areas of significant mineral resources, regardless of their conservation status or old growth characteristics, raising doubts about the quality of the agreed reserves.

Meanwhile, the forest industry didn’t have any say in the dedication of numerous reserves that added 151,000 hectares to the reserve system under the RFA process and a further 500,000 hectares in the southern forests in 2001 when plans for the new Forest Management Plan began.

The real impacts of bauxite mining in the jarrah forests

What is not fully appreciated beyond the “official disturbed figures” is that the fragmented envelopes have limited access and contain a mixture of heavy fuel and vulnerable regrowth.

According to the Bushfire Front, dense regeneration in the rehabilitated areas prevents any prescribed burning:

“…for at least 15 years which means that the fuel loads in the adjacent, unmined forest also increase. As a result, very large sections of forest have dangerously high fuel loads, predisposed to a wildfire event”.

Even though only about 25 per cent of the “mining envelope” is mined, the overall impact of clearing jarrah for bauxite mining is great – 120,000 hectares currently and 300,000 hectares in 50 years. This means that forest managers are left with a challenging and costly forest to manage. In addition, the variable nature between fuels in older mine pits and the native forest will create hot burns in some areas and too cool in others. The Bushfire Front advocates the immediate thinning of rehabilitated mine pits to reduce the fire hazards.

The dense, young, rehabilitated forests after mining use much more water than the forests it replaces. The streamflow lost to these unthinned stands costs the State $100 million per year to desalinate. Silvicultural management of the forests in a drying climate is a critical issue. A drying and warming trend in the south-west since the 1970s has led to a significant reduction in streamflow from the forest, at least partly due to heavily stocked regrowth forests. Silvicultural options such as thinning play a pivotal role in addressing this issue to maintain growth and restore streamflow. Without a market such as biofuel to allow for the economic thinning of the trees, the cost of thinning bauxite rehabilitated stands is about $40 million. If ignored, it will further compromise efforts to achieve ecologically sustainable forest management objectives.

Conclusion

Bauxite mining and alumina refining have played an important role in the economic and industrial development of Western Australia. However, what is not easily measured is whether the benefits that the government and the companies claim are commensurate with the depletion of a significant mineral resource, its impact on alternate land uses and the industry’s rate of consumption of a valuable non-renewable resource.

Alcoa’s mineral lease in the northern jarrah forest is protected by an act of parliament that provides excellent long-term security. As a result, they have been able to expand operations without developing an integrated plan to use the entire jarrah forest resource for forestry, recreation, water resource and conservation.

The sustainable harvest of native forests doesn’t have that long-term security. Operations are guided by a 10-year Forest Management Plan that outlines the policy framework for managing the native forests in the state’s south-west in that period as required by the Conservation and Land Management Act 1984.

The current Forest Management Plan ends in 2023, and the McGowan Labor government announced that the new Management Plan 2024-33 would not allow the harvesting of native forests. Instead, from 2024, timber taken from native forests will be limited to “forest management activities that improve forest health” and “clearing for approved mining operations”.

The government, however, is silent on just how much clearing occurs within the northern jarrah forests for bauxite mining. The dispersed clearing pattern required for bauxite mining creates a radical intrusion into the forest. After mining and rehabilitation, the Darling Range consists of a mosaic of small areas of healthy natural forest, mine sites that have been revegetated, dieback infected forest, rehabilitated transport and service areas, and access roads. As a result, the value as a continuous area of native forest is greatly diminished and creates management hurdles, particularly concerning fire management.

The best bauxite is under the best jarrah forest. This is because the bauxitic laterites of the Darling Range tend to occupy the gentle slopes of the upland areas, where the jarrah grows best, and it is where the rainfall is highest in the ranges.

The question that needs to be answered is why does Premier Mark McGowan think the prime jarrah forests need saving from logging when they can continue to be cleared and strip-mined for bauxite at an ever-increasing rate?

Excellent question Robert, but I doubt you’ll ever get an answer from the Premier though.

Remember this nonsense when you vote in 2 weeks.

Send a message to the ALP and their lying gren mates who have buggered native forest management in most states and then, after the cessation of fuel management, blame the fires on climate change.

It is amazing there are so many stupid people in Australia.

Excellent summary of the history of bauxite mining in WA. There is also a position paper by the Institute of Foresters (2018). Strangely, while minor forest products and honey are discussed in the Forest Management Plan, bauxite mining and its negative consequences over large areas of the forest are not.

A very good, factually accurate assessment of the ludicrous rationale to end sustainable timber harvesting in WA’s native forests on the false premise that it will ‘protect the forest’, while allowing the continuation of unsustainable bauxite mining in the forest.

Clearly, the decision to end logging is purely political – designed to win votes of the chardonnay socialists of the western suburbs, the small L Liberals, it is a ‘sop’ to the Labor left and the Greens, and internationally, it projects the WA government as having ‘green’ credentials, off-setting the environmental destruction and CO2 emissions caused by bauxite mining, in particular.

I suspect their is a strong vanity element here as well – McGowan wants to go down in history as the Premier that ‘saved the forest’. Closing the timber industry down will only impact a couple of thousand workers and their families – nothing compared to the wealth, royalties and jobs generated by the (unsustainable) bauxite mining, and the votes he will gain for the decision. Mining will cease when there’s no more forest available to mine.

Timber harvesting, which has been occurring virtually since European colonisation (almost 200 years), could continue indefinitely because today it has to comply with ecological sustainable forest management principles – tight environmental regulations controlling what, how much, where and when timber can be harvested, and the requirement to regenerate cut over areas. Not to mention that about 60% of the extant native forests are excluded from logging being in formal and informal reserves (e.g., national parks etc.), old growth forests cannot be logged, etc.

What an excellent failure in public policy….

Please note:

1. The increase in bauxite mining goes straight overseas…not even local processing to alumina

2. Mining rehab is a failure…about 3 species prosper

3. Drink your beer from glass

Mr McGowan appears to be a very naughty boy.

Kingsbury Drive near Serpentine now carries the scars of bauxite mining, an area which until recently was a pleasure to drive or ride.

The Pilbara carries big scars too, but reforestation is not part of the equation. Many WA industries are sustainable like pine, blue gum, rock lobster, wine etc but not bauxite extraction.

The reason this mining gets away with rape is the dollar and because they are not digging up your park or street. Oh yes and I nearly forgot, because there are far more creative spivs and money in corporates than in government. Not forgetting jobs, the reason so many fictitious futures are based on.

The hypocrisy of the WA Labor government is clearly set out in this article. What is the position of the Labor Environment Action Network (LEAN) in this environmentally criminal undertaking?

LEAN is a group of Labor members and supporters that celebrate Labor’s environmental legacy and campaign to ensure the environment is central to its future.

In 2018, with the backing of 500 local branches and party entities, LEAN delivered a commitment to rewrite the failed federal environment laws. These laws are failing to stem the decline of Australia’s natural environment and Australia’s terrible record of species loss. New laws will force greater protections and institutions to underpin strong policy making and delivery.

Across the states and territories, LEAN campaigns on state-based issues, ensuring Labor has climate and an environment policy to give us a safe future.

The national co-convenor of LEAN is Felicity Wade, ex-manager and campaign director of the NSW branch of the Wilderness Society.

The hypocrisy of the activist movement and green labor knows no bounds.

Robert, another succinct article that makes great sense. J

Tasmanian greens supported expansion of the dairy industry, involving permanent land clearing, over continued native forest logging, where clear fall is followed immediately by regeneration.

In central Queensland, the mining industry consultative group, ignored my suggestion of establishing Rosewood forests on reshaped mined areas, mainly due to the green propaganda that all forms of native forest harvesting are bad. Rosewood forest is logged for fence posts every five years in established forests.

Greens are now claiming that carbon sequestration only occurs in forests that are excluded for any harvesting.

I wonder if there will ever be an end to their nonsense.

Many thanks, Robert.

This is one of the saddest reports I have read on forest land management.

It fills in the gaps between my memories of the early developments at Jarrahdale and my remote acquaintance with mine site rehabilitation in the last two decades. It shows the overriding authority of legislation promoting mining, the deliberate exploitation of that power by the mining industry, the willing acquiescence of governments to that power and to the royalties that flow, the uninformed pressure by sectors of society that oppose scientific and sustainable land and water management, and the acquiescence of governments to that pressure.

Professional foresters can feel proud that they called for the long-term costs and benefits of alternative land management options, but it does not lessen the pain of realising that the government has been dazzled by the ephemeral income produced by mining bauxite and has been persuaded by political interest groups that the best land management is no land management.

What scale of disaster will be required to alter that perception? Khartoum and Mariupol, perhaps?

The hypocrisy of the McGowan Labor Government is breathtaking, as is the silence from the leftist green anti-logging brigade.

No cost benefit analysis has, or ever will, be undertaken by this or other WA governments, as they don’t want the taxpayers to discover the horrific environmental damage that bauxite mining companies are doing. Nor do they want the downstream cost to the taxpayer disclosed.

The net result from mining our jarrah forests is that no income is being generated, a situation now made worse by the export of the raw material, further reducing any opportunity to create employment here.

On the other hand, they are quick to close down the sustainable timber industry to feather their own nest and egos. Stuff the people in the bush, the votes from the metro area are far more important.

Further, the Labor Government was quick to stop and rehabilitate the Roe Highway extension in Fremantle to appease the local and vocal green minority there. This is in complete contrast to the Bunbury Outer Ring Road southern section which will destroy a vast swath of critically important marri forest and banksia woodlands when a far better option exists. The alignment should have followed the mostly already cleared areas a short distance to the east.

Where is the EPA in both these issues? Missing in action and under instruction from the government to do their bidding!!!

Evo.

If the mining can’t be stopped, at the least the mining companies must be compelled to undertake silvicultural management of the regenerated areas, such as thinning and prescribed burning, in cordination with the surrounding unmined forest.