While I stayed at Walpole, I read about a local forester named John “Jack” Henry Rate. Jack was the first forester in the area and has a tree, lookout, road and a forest block named after him. I had never heard of him before, and I thought he should be more widely known with that many accolades, particularly in the forestry profession.

John was born in England in 1909. His parents migrated to Australia in 1923 and were placed in one of the first the Group Settlement Schemes to create dairy farms in the Manjimup area. They were in Group #90 along the Channybearup Road between Manjimup and Pemberton. When he was 17 years old, Jack took up Block #10080 next to his parent’s farm. Jack then befriended the Gunson family who owned a Group Settlement farm nearby. After Alfred Gunson broke his leg in a horse and cart accident, and was sent to hospital in Perth in 1929, Jack helped Alfred’s wife, Edith, run their farm.

In 1930, the first family tragedy occurred after Jack’s father was killed when kicked in the jaw by a horse whose tail he was docking.

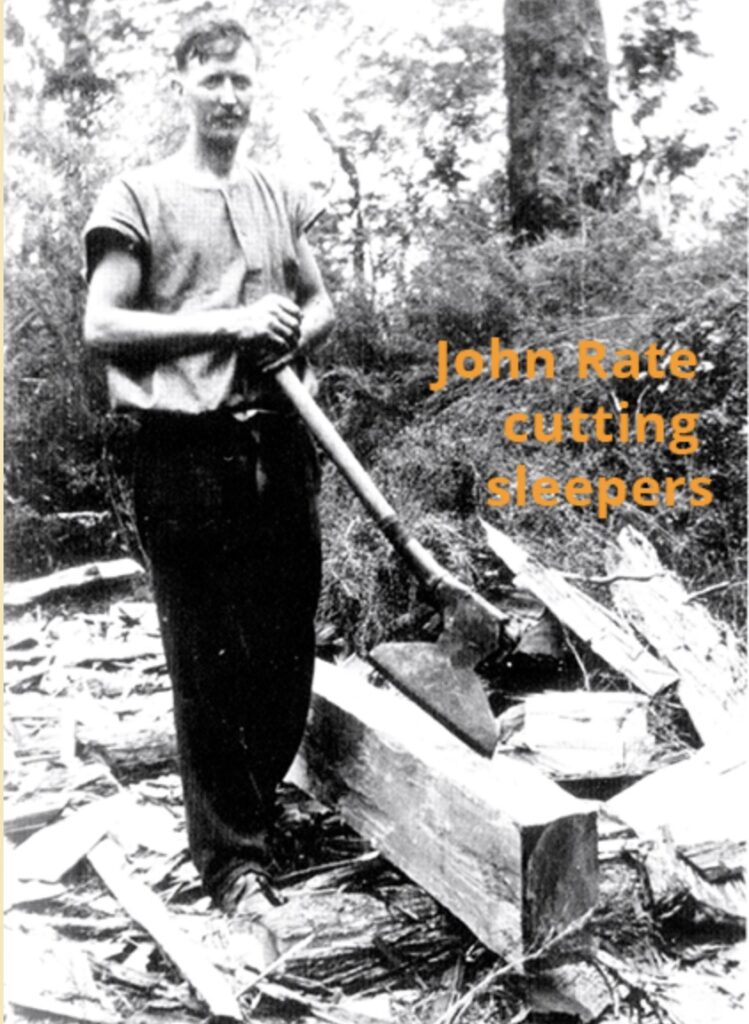

During the Great Depression, and for most of the 1930s, Jack worked as a sleeper cutter using the broadaxe and adze deftly. He camped in the forest and could split up to 12 sleepers per day.

In the 1940s Jack worked for one of the Pemberton sawmills as a tree faller and log hauler and in 1946 he joined the Forests Department, working out of the first Southern Divisional office based at Pimelia, north-west of Pemberton. In the meantime, Alfred and Edith Gunson had become estranged since the early 1940s and were divorced in 1947. In that year Jack married Edith and they moved to the state’s last declared Forestry Division office at Shannon in support of the new sawmill.

By 1950, Jack was back working in Pemberton and the following year was transferred from Manjimup for Walpole district as the district’s first resident forester. He had just returned from a three-month tour of New South Wales with Edith. Walpole was the only district within the Shannon Division.

In addition to his duties as a forester, Jack was appointed Honorary Ranger of Nornalup National Park to replace part-time ranger Tom Swarbrick Snr who had been in that position since 1927. This was an unpaid position. Thanks to Jack, the park got its first full-time ranger, his step-son, Lionel Gunson, who was also the first full-time ranger to be appointed in Western Australia. In addition, the Nornalup Advisory Committee was formed to provide local input into management, resulting in a more strategic approach to conservation management in the park.

The unique tingle eucalypt trees are only located in the wet forests surrounding Walpole, between Deep and Bow Rivers, over approximately 6,000 hectares. There are three separate tingle species.

The main one is red tingle (Eucalyptus jacksonii), and it is undoubtedly an interesting and unique eucalypt. It grows on laterite soils overlying a relatively shallow granite bedrock. While it is named for its distinctive red wood, and has the typical morphological characteristics to identify it as a eucalypt species, it doesn’t have a taproot, which is critical for eucalypts to find and tap into water underground. Instead, it has a shallow root system that spreads as it grows to cause the tree to buttress, a very unusual feature in eucalypts. Red tingle trees have massive trunks that can be up to twenty metres in circumference. They can also grow to 75 metres in height and are known to live for over 400 years.

One other feature of red tingles is the hollow butts on the larger older trees caused by fungi, insects and fire. If you visited the tingle forests before the 1990s, you probably drove your car inside an old and iconic tingle that had a large hollow at the base for a great photo opportunity. But unfortunately, the tree eventually died and fell over.

One somewhat quirky feature is red tingle doesn’t start to flower until 32 years old, when it produces small white flowers in the late summer and early autumn. After that, it does so every four years.

The other relatively familiar tree is the yellow tingle (E. guilfoylei) which is not as tall and does not buttress. The timber is a rich yellow colour, straight-grained, dense and durable. They grow to around 35 metres in height. It is taxonomically unrelated to red tingle being in the subgenus Cruciformes (red tingle is in subgenus Eucalyptus). It differs in having terminal inflorescences or flower arrangement, buds with an operculum scar and ovules in four to six rows on the placenta (you need a microscope to detect the last feature).

In the late 1960s, Jack noticed what he believed to be a different tingle species from the two already known and described. He collected botanical specimens from this other tree to aid in identification using a homemade slingshot to shoot down fresh leaves, fruits and buds.

The samples were sent to the Western Australian herbarium to see whether it was a different species. The news came back that it was indeed a new species. Foresters requested that the tree be named to honour Jack. World-renowned eucalypt expert, Ian Brooker, who declared it a new species, unfortunately named it Eucalyptus brevistylis after its short styles. It was a kick in the guts to Jack and the forestry profession where a diligent forester went to all that trouble to identify a new species and was proven correct. As a consolation, Roger Underwood suggested that the common name be Rate’s tingle, which stuck.

Rate’s Tingle is not easily distinguished from red and yellow tingle. It can grow as tall as red tingles, but to differentiate it, you have to find the waxy looking leaf stalk, heart-shaped young leaves and wrinkly looking gumnuts. It grows in small groups or as a single tree, north-east of Walpole.

During the 1960s, Jack played his part in the development of a new fire management system that grew out of the ashes, inquiries and soul-searching that followed the devastating Dwellingup fires in January 1961. Western Australian foresters pioneered aerial prescribed burning as a means of covering large areas that were required to be burnt across the landscape to manage fuels and fight the inevitable wildfires.

According to retired forester Noel Ashcroft, Jack was a strong supporter of prescribed burning and was directly involved in developing and planning the aerial burning program in the district. He didn’t fly during the burns as that was left to trained navigators and bombardiers. Noel recalls working with Jack:

“When conditions were right, and I was in the district, the two of us from time to time did some edging in the North Walpole area, an area of high forest interspersed with farmland and difficult to burn once the grass had cured. We made safe several heavy fuelled pockets adjacent to private property in this way at the time”.

In the late 1960s, Noel was responsible for transferring the Shannon River forestry settlement into Walpole to consolidate resources in one area and create a new Divisional office based at Walpole. The Shannon River karri mill had closed, and mill houses sold and removed. Noel and Jack worked closely together to develop a new housing area, new office and operations yard and workshop in Walpole.

Jack was described as a gentle, humble, and quietly spoken man who had an excellent knowledge of the south coast forests. He had the respect of the timber industry that he oversaw in the Walpole, Denmark and Albany areas, along with the Walpole townsfolk and the farming community. With the latter, his skills were greatly needed, particularly with land classed as “Private Property Timber Reserved” (PPTR) to the Crown. Farmers could clear or ringbark the trees, but they could not sell them. That was the domain of the Forests Department. The sawmill at Walpole was primarily set up to cut timber on PPTR land. PPTR conditions had a sunset clause and were due to expire around 1970. The Forests Department was keen to access as much of this timber as possible. This created conflicts with farmers who owned that land, and the Department’s image was tainted for many years.

Jack did his best to deal with aggrieved farmers who had timber on their property allocated to the PPTR system. It was essential to maintain cooperative arrangements with the farmers, especially for joint burning programs.

Unfortunately, Jack died in a horrific accident while at work on 23 December 1969. Noel recalls the events of the day that lead up to his death:

“In the course of our association, Jack had casually mentioned to me that he had never seen his district from the air.

Fortuitously, on the day he died, we had been doing an aerial burn in the Broke Inlet area, and I was in the aircraft with Mike Rowel and Gerald Van Didden. We had concluded ignition, and I recalled what Jack had said and arranged for them to give Jack a bit of time in the air so he could look around the area. That proved possible, and I radioed Jack to get the Shannon airstrip where I was to be dropped off, which he duly did. He was given a good look around, and when he returned, he was most pleased to have achieved that long-held desire.

I then returned home in Shannon River (where I was to receive the tragic phone call), and Jack returned to the burn at Broke inlet where his crew was working on a hop over between the South West Highway and the western end of Broke [on Woolbale Road].

When he arrived back at the burn, he found Alan Hatfield on the 4×4 bladed tractor clearing scrub around a tree alight in the crown. He was standing alongside the machine giving Alan instructions to achieve a safe situation when, in a split second, a branch came down and killed him instantly. As Alan was talking to him, he was felled before his eyes!

Contrary to reports in the media and interpretive signs, it was not a karri branch that killed Jack. Instead, it was a large marri branch from an old gnarly tree that had caught fire in its crown. The Walpole gang subsequently felled the tree, and, using a chainsaw, they inscribed into the bole the initials JHR as a memorial to Jack.

This was a tragic end for a man who was passionate about the forests. Sadly, his wife Edith had died only a month earlier.

As a result of this terrible accident, and as I mentioned previously, several local forest features were named after Jack. Apart from Rate’s tingle, the lookout is probably the most widely known of his memorials. It was built soon after Jack’s untimely death and is located about five kilometres west of Walpole on the South West Highway. While the lookout did offer superb views of the Walpole and Nornalup Inlets Marine Park, sadly, these days young regrowth trees intrude on the view.

Thank you Robert

What a tragic end to a man who loved trees and dedicated his life to the forests.

Thanks Robert for highlighting his life.

Very interesting, I am his grandson.

Interesting read, thanks Robert.

I can’t help wondering what will be the fate of these forests in SW Western Australia and in Victoria when sustainable harvesting of native forests ceases in the near future.

Thanks for all your blogs Robert. I was married in Manjimup where my wife was born and have visited the area many times before and after her death until the death of my mother in law. I have always wondered about Jack Rate and now I know. Thanks, George.

Glad to read this story. I am his grandson living in Manjimup.

Another great story, worth telling and told well.

The mention of Jack using a “ging’ (slingshot) reminded me of the way items can have different names in different places. Having married a West Australian I learnt that what I (NZ born) called a shanghai was called a “ging” in WA. I might be wrong but suspect it is very specific to there.

Interesting story, Robert. When I grew up in the 1930s near Proserpine NQ, shanghais were called “gings”.

Peter Kanowski Sr

As a kid growing up in NSW we called them slingshots. My Victorian sources said they called them a shanghai but occasionally a slingshot or a catapult.

A quick google and dictionary search reveals other names such as beanshooter (American), kettie (Sth African), gulel (Indian), pachoonga, gonk and dong-eye!

I can see a future blog on this topic!

What a great story, thank you so much for taking the time to put this together. Amazing how much more there is to the story than what we’re commonly told.

Thank you for sharing this story. Never have I seen these photo’s before! For context, I am the granddaughter of Lionel Gunson.

Thanks for sharing the story Robert.

Very interesting to know more of the backstory of his life. My Grandfather Nick Powley worked for the Forestry Dept in Walpole at the time.

I used to spend many of my school holidays in Walpole with my grandparents and I remember Mr. Rate getting killed, although I am not sure if grandad was at the same site when the accident occured. Sadly Grandfather Nick passed away in 1970 and Grandmother Jean moved back to Denmark. I am pressuming she had to leave the house that was provided by the Forestry Dept.

Thank you for sharing this story on Jack Rate. Really enjoyed reading his life’s story and see the photos. He was my Uncle. Eric Rate was my father and Jack was his brother.

Thank you for the great story. My father was Alan Hatfield, and I do recall this happening. He was very emotional about it.