This month’s guest blog is written by David de Little.

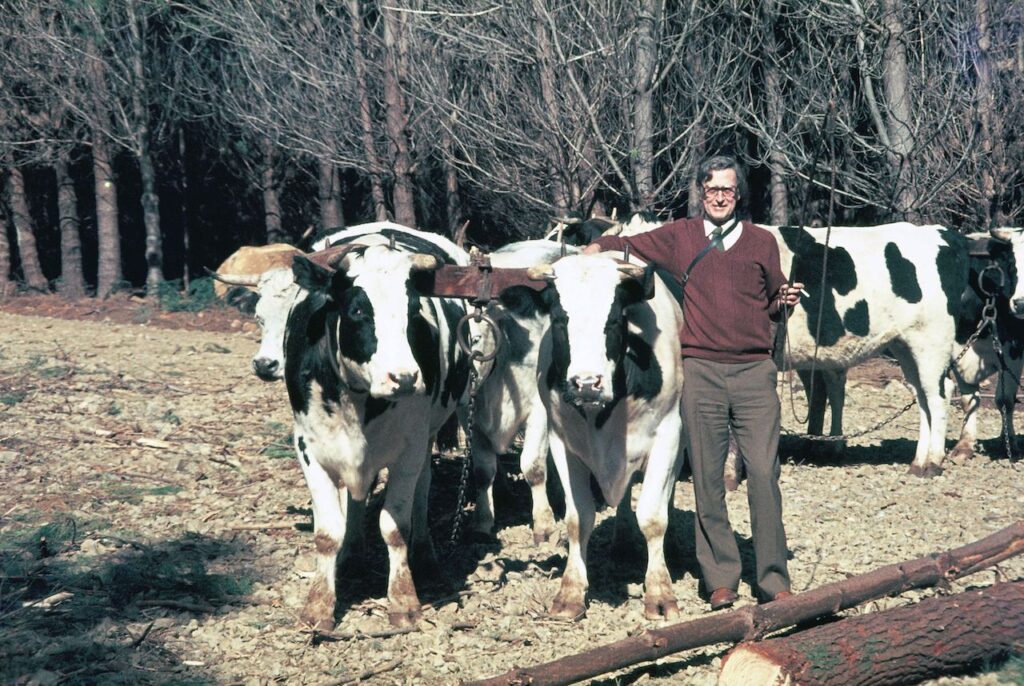

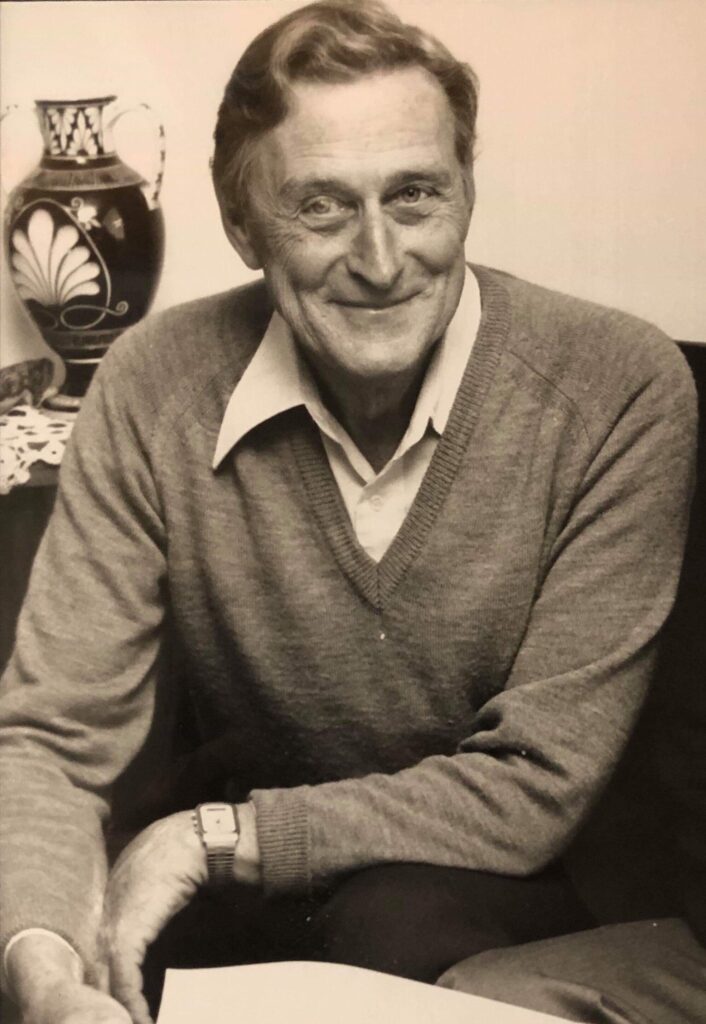

In my book “Fires, Farms and Forests” I outlined the pivotal role Dick de Boer played in the development of eucalypt plantations on Surrey Hills. David was fortunate to work with Dick from 1975 to 1983 and got to know him very well. There was more to Dick than just Plantations Superintendent at AFH, as David outlines below.

David worked at AFH, North Forest Products and Gunns from 1975 until 1985 as Research Officer, and from 1985 to 2002 as Forest Research Manager. He gained his PhD from the University of Tasmania in 1979 for his thesis, “Taxonomic and ecological studies of the Tasmanian Eucalyptus-defoliating Paropsids”, and managed the company’s tree-breeding program from 1983 until 1997.

David would like to acknowledge the assistance of Bernard de Boer and Geoff Dean in writing this blog. Also, thanks to Hans and Nanette Drielsma, and Kaye Green for inspiring him to re-visit old memories.

In 1975 I was half way through a PhD study on gum tree leaf beetles which were in out-break, and a major issue for Tasmanian forestry in the 1970s. The Tasmanian Forestry Commission was interested in my research and looking to appoint a forest entomologist. However, when a newly “doctored” forester was appointed to that position I had to look for an alternative. Dick (Dirk) de Boer of Associated Forest Holdings (AFH) was also interested in my research and, although I didn’t realise it at the time, my agricultural science, rather than forestry, background. I had met Dick while undertaking a state-wide survey of the leaf beetle problem and we had instantly “clicked”. Dick’s background was not that of an orthodox forester as I was soon to discover.

At that time the conventional method of regenerating wet eucalypt forests (mainly Eucalyptus regnans) was to clear-fell coupes, burn the slash and aerially seed the new crop. This worked well for low to medium altitude forests, but most of AFH’s forest estate consisted of high-altitude E. delegatensis forests that did not respond well to this or other disturbance techniques. The result was a slow regeneration of mixed eucalypt and rain-forest species. When it was suggested to Dick, who was by this time in charge of the company’s Pinus radiata plantation program, that maybe eucalypts could be planted in the same way as pines, in order to enrich the poor eucalypt regrowth, he jumped at the opportunity to test the idea and prove that it could be done. Fragments of this story, together with the story of Dick’s amazing life, gradually unfolded as I accompanied Dick around the AFH forest estate early in my employment, and also when invited to his home on many occasions.

Dick was born in 1922 to Dutch colonial settlers in Indonesia, then known as the Dutch East Indies. His father was an architect who made a study of the Hindu temples of Bali. In 1940, just after the outbreak of World War II, Dick travelled to the Netherlands to study medicine, unfortunately arriving just after Nazi German occupation. A condition of university study was collaboration with the occupying forces. Dick, realising that he could complete a Tropical Silviculture qualification in two years, thought that he might more quickly return home if he undertook this course. However, on his completion of the degree, the Netherlands was still occupied, and this was to continue for another two years. At this point Dick, having agreed to collaborate in order to undertake his study, joined the underground Dutch resistance movement, knowing full well the dire consequences were he to be found out.

As a resistance fighter, in order to arm himself, Dick had to steal a revolver. This was done by entering a barber’s shop where a Nazi soldier was having a hair-cut. He had taken off his holster belt containing his revolver and hung it on a coat hook. Dick placed his own coat over the top of this and waited until the soldier’s attention was otherwise occupied. At this point Dick got up, retrieved his coat together with the revolver underneath it, and vacated the shop. There was also the story of the stolen military motorbike which soon needed refuelling. A likely looking drum was located and the bike refuelled. The only problem was that it was aviation fuel which promptly exploded when the motor was started. During this period Dick was incarcerated on at least one occasion. Subsequently, he was unable to be in a room with a naked light globe. Years later in Tasmania, as AFH Plantation Superintendent, Dick had occasion to call on a neighbour of Germanic background to discuss a boundary issue. The turn of conversation led Dick to suspect Nazi sympathies. At one point this neighbour needed to take his attention from Dick and at this moment Dick’s underground observational training came to the fore with his spotting of Nazi memorabilia in the room.

At the conclusion of the War, Dick returned to the East Indies which had been under Japanese occupation. His father had been killed, but his mother and younger brother had survived in a Japanese Prisoner-of-War camp. Dick commenced work establishing rubber and coffee plantations in remote areas of Borneo and Celebes. This sometimes involved travelling up rivers by boat. At one remote village his party was only the second party of white people seen by the indigenous inhabitants. The first party had made an impression because their images had been carved into totem poles. It was while in Borneo that Dick had a profound experience that led to his respect of and compassion for workers under his supervision. Prevailing colonial attitudes were of white supremacy and authority, and Dick was no exception until taken aside by a local chief and lectured on the importance of respect and empathy for all people.

Around this time Dick married Elize Wyker, who with her family had also been imprisoned by the Japanese. Their eldest son, Edward, was born in 1949 as the Indonesian independence movement was gathering momentum. It became necessary for Dick and family to leave the future Indonesia rather hurriedly. Although initially deciding to settle in New Zealand, they met and were befriended by Terry White of the Australian Diplomatic Service, who was originally from Devonport. He persuaded them to visit Tasmania first, resulting in them staying, and in Dick finding forestry employment on the North West Coast.

Dick secured employment with the forestry arm of the Burnie Paper Mill, specifically to initiate a pine plantation program in order to supplement the short fibred eucalypt pulp with a source of long fibres. At this stage, what later was to become Associated Forest Holdings, was based at Guildford Junction near Waratah in the centre of the forest estate. This settlement, which no longer exists, has been described as having the most miserable climate in Tasmania – quite a contrast to the tropics! When Dick tried to light an indoor fire by holding a struck match to logs from the damp outdoor wood-pile, he was surprised that it did not ignite spontaneously. On another occasion, Elize was asked to “bring a basket” to a social function. She thought this a strange request but did so anyway, only to find out that the basket was supposed to contain scones or cakes! Over the next few years Dick and Elize’s family grew with the addition of three more sons, Richard, Bernard and Leonard.

Around 1960, AFH moved its headquarters from Guildford to Ridgley in the hinterland behind Burnie. Dick and Elize built a lovely home overlooking the Pet River Reservoir with a view to St Valentines Peak in the distance. Not long after this, tragedy struck with the death of their eldest son, Edward, on a school excursion at Cradle Mountain. A few years later their second son, Richard, also died tragically in a car accident.

The idea of taking the trouble to raise eucalypt seedlings in a nursery and plant them in the bush seemed nonsensical to Australian wisdom of that time. For the past 150 years settlers had been trying to clear land for settlement and farming, and the almost instantaneous regeneration of eucalypts was often seen as a nuisance. As mentioned, by the 1950s this

regeneration phenomenon had been harnessed by the forestry industry to restock depleting forests. However, the forests of “Surrey Hills” presented a unique situation and required thinking “outside the square”. Due to extremely small seed size, eucalypt seedling germination and nursery treatment had to be very different from that for Pinus radiata. Dick

had already shown his unconventionality and put his job on the line by successfully transplanting one-year-old pine seedlings directly to the field. This was to become standard practice, instead of the conventional practice of transplanting two-year-old, hardened stock which suffered more transplantation shock.

Dick and his team developed a system of “pricking out” the tiny eucalypt seedlings from germination trays and individually transplanting them with tweezers into paper pot cells filled with sieved forest soil. The one-year-old seedlings were then planted into the field when about 15 centimetres tall. Initial attempts to establish eucalypt plantations were beset with the problems of weed competition, animal browsing and insect defoliation. Even if seedlings of the local cold-adapted species, Eucalyptus delegatensis, established well, they just stopped growing after a couple of years giving weeds a chance to take over. It wasn’t until much later that it was established that this “arrested development” was part of the natural growth habit of this species. Despite these set-backs Dick persisted. Even when instructed to stop “wasting money” on his research, Dick built himself several fictitious miles of road to provide himself with a clandestine research budget.

A major breakthrough came around 1970 with the discovery of Eucalyptus nitens (“Shining Gum”) a native of the alpine regions of mainland south eastern Australia. Although the seed size was even smaller than E. delegatensis, this species did not suffer from arrested growth and after a couple of years quickly dominated plantation sites. The fact that the first kilogram of E. nitens seed purchased cost more than a kilogram of gold was an off-putting factor until it was realised just how many potential trees it contained. When seen how spectacularly successful the growth of plantations of this species was, other forest enterprises quickly followed suit in establishing shining gum plantations.

Despite his dedication to pioneering successful eucalypt plantation forestry which subsequently spread to many regions throughout Australia, Dick was a keen observer of all aspects of the natural forest environment. When, not long after I had met him, he wanted to show me the “platypus in the myrtle trees” I wasn’t at all sure what I was going to see. In fact, the “platypus beetle” is a tiny wood boring beetle that attacks myrtles (Nothofagus cunninghamii), introducing a pathogenic fungus that eventually kills the trees – a discovery made by Dick. He took a great interest in the eucalypt defoliating beetles I was studying, introducing me to specialised photography with his own skilfully executed images. It was a great sadness and frustration to Dick that due to his work commitments he was unable to take his scientific studies further in a formal sense. Despite this personal disappointment, Dick encouraged contact with CSIRO and universities, leading to many collaborative research projects, one resulting in my employment by AFH.

Apart from his employment commitments, Dick was heavily involved with his sons’ school, preparing and executing the landscape plan for Parklands High School. He also served on the Burnie Municipal Council. An indication of his sensitivity to the local cultural landscape was evidenced by his devastation when the remains of the early nineteenth century Van Diemen’s Land Company station at Hampshire were bull-dozed in an act of wanton destruction, after he had given an undertaking that they would be unaffected by plantation development in that area.

In recent months, I was contacted by a mutual friend of a family whose parents had known Dick and Elize de Boer in Indonesia. A death in that family had resulted in the finding of a copy of the eulogy that I had the privilege of being asked to give at Dick’s funeral in 1994. This was very fortunate as subsequent moves had resulted in me having lost my own copy. This fortuitous finding has given me the opportunity to refresh memories and reflect on the many aspects of this great mentor in my career. It is sobering to reflect that I am now nearly the same age that Dick reached, and to realise just how much life and achievement, despite devastating set-backs, Dick packed into those three-score and ten years. I hope this small contribution has helped to perpetuate his memory.

This story about Dick was too good not to be recorded for prosperity. Thanks for doing that.

Thanks Ian for your comments. Hope you are keeping well.

Cheers Dave

My family lived in Guildford 1950 – 58. My father worked with Dick at times. I remember Dad telling me of Dick learning our Aussie speech and behaviours. I was in the same grade at school as Edward. We were young mates. Mrs de Boer was an excellent seamstress. I enjoyed this story. Thank you.

I started work at Ridgley AFH in 1977 at the age of 18. After washing the trucks we would go for drive out to the Granites. Together with his moody dog, Scamp.

What he accomplished might have only been possible because he was a gentleman from Holland who sidestepped large, loud men that were predominant in Forestry at the time.

I remember Dick de Boer well, I met him a few times. I was astonished to read about his time as a resistance fighter. He seemed to me always a more quieter man.

Thanks for the writer of the story, it had to be written.

Some of my fondest memories of my time at AFH/NFP were when I started back in 1973 working with Dick and later Dave de Little on the eucalypt program.

I still remember going out each week to the trials to measure beetle eggs, larvae & adults.

Would bring back the results and Dick would often make the comment “Cor Bloody Hell” we have a problem!

Great man.

An enthralling account of a life well lived. My special thanks to David and Robert for perpetuating this piece of family history and also to the people whom have responded with kindness and respect toward Dad’s memory.

Hello Bernard. I was a friend of Edward while my family Strudwicks, lived in Guildford.

We did come and visit your family a few times when you moved to Pet Dam house. It was fun there as all us kids used to go across and play on the empty spillway!

I went to Burnie High School and Edward went to Parklands and it was sad indeed when he died on the school trip. Your dear parents had tragedies in their lives.

Your mother helped my sister Faye, make her wedding dress in about 1965. I hope life is good for you.

Regards Wilma Aherne, Devonport.