While visiting Cardwell in North Queensland, we enjoyed the forest drive in Cardwell State forest. We stopped to look at Attlie Falls, and as I walked the short distance, my focus was towards the ground. I noticed bark on relatively large trees resembled a Pinus spp (an exotic pine tree). I had a brief but strange thought I was walking through a very mature pine forest until I looked up and realised I was looking at one of my favourite eucalypt trees.

I was first introduced to this tree when I worked at Hyne & Sons’ pole plant in Maryborough during the summer school holidays. Given my father worked for the company, and I was just a scrawny teenager, the job they gave me was what no-one else wanted to do or just wasn’t a high priority. I had to mow and whipper-snipper around the numerous stack of poles. All day, for weeks, I mowed and snipped without any PPE.[1] I can guarantee that the pole yard never looked in better shape when I was working there.

I was excited when I was promoted to help build playground equipment after completing the tidy up. Buyers could order a range of equipment that was pre-built using treated hardwood timber and dismantled for transport around Australia. Most of the playground consisted of a square frame with different configurations around that. We would stand four poles in a concrete-lined hole and drill holes to attach the supporting beams. We built platforms to support slides and steps for children to climb up.

However, the real excitement came when I was asked to do a real job – pole dressing. This job was the pinnacle of pole yard work, and I couldn’t wait to use the drill with the two-inch thick bit to drill holes for the cross-arms; the electric planer to smooth out the knots; and put the metal cap on the top of the pole. I didn’t much like, however, debarking using a shovel. Poles had to be delivered to the yard from the bush debarked, but there was always residual bark still on the poles. Before going to the cylinder to be impregnated with Copper Chrome Arsenic (CCA),[2] we recorded the dimensions and details on the butt end of each pole.

I remember asking what species a particular pole was before putting the species code on the butt end. I was told it Gympie mess, mate. I thought it was a strange name to call a tree – Gympie mess. It wasn’t until much later I realised it was Gympie messmate (Eucalyptus cloeziana). It is a relatively large tree growing over 40 metres tall and is endemic to Queensland. It is very durable and used for heavy engineering, sleepers, poles and scantlings.

At the end of my university studies, I was at home while I searched for a forestry job. I worked with Hyne & Son again, this time in their technical section. My main task was to conduct in-house quality control of treated poles to ensure that the minimum retention levels met the Timber User’s Protection Act 1949-72. I collected small plugs from a sample of treated poles. We used a portable ‘Asoma’ x-ray fluorescence machine to assess retention levels in the ‘analytical zone’ which is the inner one-third of the treatment area in the sapwood. The company avoided the costly and time-consuming process of employing full-scale laboratories to do the analysis. More importantly, if a sample showed minimum retention levels were not obtained, appropriate action could be taken almost immediately after the treatment process.[3] I recall that Gympie messmate had the highest retention levels over most other species, including spotted gum (Corymbia maculata).

When I worked on the NSW north coast a few years later, I came across Gympie messmate again in small plantations on ex-banana sites in Pine Creek State Forest, just south of Coffs Harbour. They were planted in the early 1940s.[4] Pine Creek State Forest is familiar to foresters that studied at The Australian National University in Canberra. Each year, a cohort of students in their later year of study, would spend a few weeks there as part of silviculture training. The very early days had foresters wielding axes, but in our era, the work was a bit more sedate under the direction of our erstwhile lecturer, Dr Ross Florence. We learnt a lot about mixed species and blackbutt silviculture.

The opportunity to manage Pine Creek as a forester was exciting, especially as I already knew a little about it. I worked closely with the foreman, Jack Burke, who had worked in the area for 40 years and followed his father, Sid.[5] Jack knew everything and told me stories about Pine Creek State Forest’s history east of the old Pacific Highway. When hosting an archaeologist for the Environmental Impact Study (EIS) I helped prepare for the district in the early 1990s, he showed us historical sawmill sites and described how the area was originally cleared and farmed. After World War II, farms were purchased by the government and dedicated as State forest. He pointed out old banana growing areas that now support Gympie messmate plantations. He was also a bit of a raconteur and had a dry sense of humour. A favourite I recall was when we were in a swampy wet section near the northern boundary, and we were getting attacked by mosquitoes. Not just ordinary mosquitoes, but much bigger ones that Jack dryly said “were so big you need a rabbit trap to catch them”. I also remember him wielding his brush hook to cut a water vine to prove to me how much water they carried and how nice it tasted.

One memory of Pine Creek that I will never forget is walking through a coupe one day by myself, as part of planning a logging operation. I came across a person sitting under a blue tarpaulin completely naked playing the guitar. Middle of nowhere, not near a road or track just sitting there, starkers. I saw an old blanket and a large container of water. I tried to talk to him, but he just looked at me with glazed eyes. I left telling him he had to move on as it was illegal to camp in the forest. A hippie commune was nearby at Bundagen, and I spoke to one of my contacts. He told me about a dispute, and the squatter was kicked out of the commune. I wasn’t exactly told what the disagreement was over, but it is a fair chance it had something to do with a recreational smoking habit.[6]

In recognition of forester’s management skills over nearly a century, the forest east of the highway is now a national park. In a daring example of re-writing history, or just plain ignorance and hubris, the management plan for the newly created Bongil Bongil National Park shows utter contempt towards the Burke’s family legacy by claiming the rest area was created by the Roads and Traffic Authority and not the Forestry Commission. Nor is there any recognition given to the old sawmill sites, which are publicly available in the Environmental Impact Statement, as well as separate archaeological studies. Interestingly, the management plan boasts, in its historical section, that the creation of the national park was due to local ‘conservationists who campaigned extensively against logging operations and the likely impacts on the local koala population’. There is no acknowledgement that the environmental values that exist at Pine Creek were established from only 60 years of forest cover after the area was previously cleared for farming. It supported sawmills, dairy and banana farms, a school, several houses, many logging events and intensive silvicultural operations such as timber stand improvement and snagging, which removed large trees near roads to avoid the chance of embers or trees falling over the road during a fire. Despite being subject to these despised forestry management practices, the forest still supported populations of powerful owls, koalas, yellow-belied and greater gliders. The question is, are they still there under the current management of benign neglect? One only has to replicate the fauna studies carried out for the EIS in the area to find out.

The tragedy is a rich forest utilisation history has been arrogantly obliterated from the records. Unfortunately, such brainwashing of real history to fit a narrow ideology is all too prevalent in our society today.

[1] I am convinced my current hearing problems stem from this experience.

[2] From the late 1960s eucalypt species used for transmission poles throughout Queensland underwent a preservation treatment process to protect the non-durable sapwood. Hyne & Son used a vacuum pressure impregnation system with a preservative solution containing salts of copper, chromium and arsenic (CCA). Because of the high degree of variability in the structure and the density of eucalypts, different species required different CCA treatment levels to ensure the minimum requirement set under the legislation was met.

[3] A summary of this work, and issues faced, is in an unpublished paper I prepared in 1987 for Hyne & Son called ‘Problems associated with the quality control of treated hardwood poles’. I can provide a copy to anyone interested in reading it.

[4] Gympie messmate is a popular plantation species overseas, particularly in Zimbabwe. But like most eucalypts in Africa, they are voracious in their use of water and interestingly, display strong allelopathic tendencies. What this means is they inhibit the growth of native flora nearby.

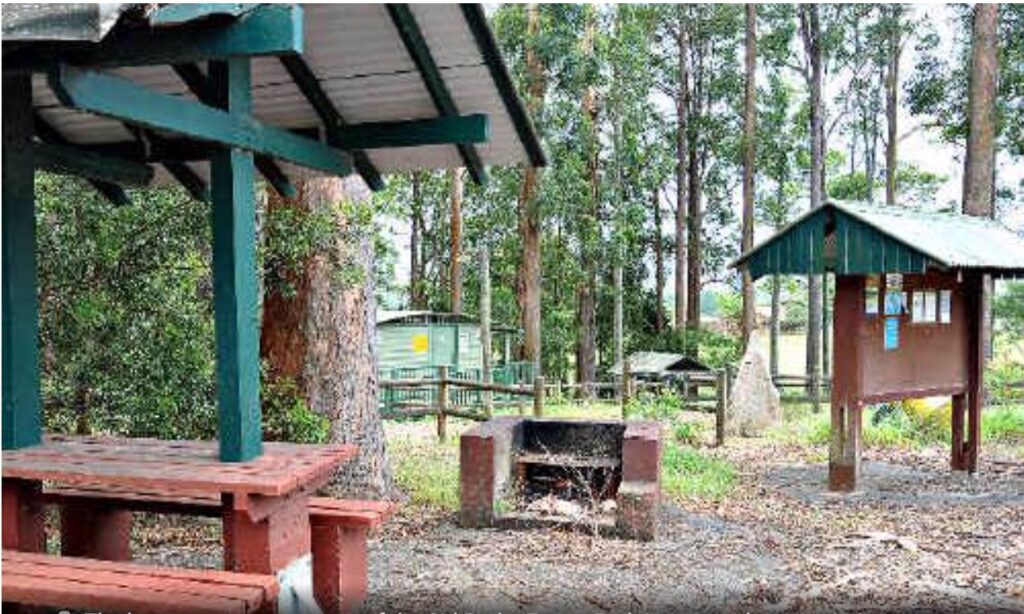

[5] In 1978, The NSW Forestry Commission dedicated a small rest area in memory of the late Sid Burke. For 25 years he was the foreman at Pine Creek and was well known to numerous students who took part in the annual study trips. The Rest Area has been a popular rest stop on the Pacific Highway, some 16 kilometres south of Coffs Harbour. It attracted over 50,000 visitors a year. It is now part of Bongil Bongil National Park, and responsibility for management was transferred to the National Parks and Wildlife Service in 1995. I understand, however, that management responsibility was subsequently transferred to The Roads and Traffic Authority. The rest area was closed in 2006 as part of the highway upgrade and the highway now by-passes it. The Rest Area is still there and is a popular gathering point for local road and mountain bike riders. But its future is uncertain. It must be disappointing for the Burke family and their friends that an area dedicated as a memorial for Syd Burke’s achievements at work and his contributions to society, including service in World War I, can gradually lose its significance, be forgotten, and treated with disdain by uncaring bureaucrats.

[6] Bundagen is a commune established in 1981. It came about when a development company planned to buy some freehold land at Bundagaree Headland for tourist development. Environmentalists formed a company and raised funds to buy the land, and the legal structure was set up as a co-operative.

In 1991 Forestry Commission research established that koalas on the north coast were strongly associated with dense regrowth forests created by intensive logging and plantations. There were three times as many as in unlogged forests. In 1995 the National Park was created to save koalas. Koalas are now in plagues throughout the forests young and old because they are sick from lack of mild fire. They are turning over soft young foliage all the time.

Keep documenting these stories Robert.

There were trial stands of Gympie messmate in the copper belt region of Zambia when I worked there for UN FAO. They did not grow as fast as Flooded gum but they both were both prodigious users of water as you say. Plantations had a very strict thinning schedule – missing the required schedule by a year could result in the whole plantation dieing of drought stress during the prolonged dry season.

Thanks Phil. When I went back to South Africa in late 1993, I was surprised at the amount of eucalypt plantations (in fact on my travels to different places in Europe and Asia, I have always seen the ubiquitous eucalpyt). They were mainly planted on the foothills of the eastern ranges in variable climates. The foresters I met at Franshoek told me that they were heavily criticised for planting water-hungry trees in a savannah landscape. They referred to them as ‘thirsty invasive plants’ drawing water from the high rainfall areas on the ranges before they got to the drier savannah plains below. E. grandis was the main species they mentioned. I recall they mentioned impacts on the Kruger National Park and how it was a big conservation issue at the time. The foresters were surprised when I told them the situation was the opposite in Australia – you were criticised for cutting down trees and there were government-funded schemes to promote tree plantings, after a century of government encouragement to clear and ‘improve’ land east of our Dividing Range.

G’day Phil and Robert,

Gympie messmate is an extremely efficient species that can grow well on a wide range of sites from sand over clay or water to highly fertile deep red basalt soils at Toonumbar. There was a plot at Tabbimoble near Little Italy that towered above the native blackbutt woodland. But like all eucalypts it can’t tolerate deleterious soil changes in the absence of mild burning. I think that the photo of the plantation near Gympie at the start of the article illustrates declining trees with crowns of epicormic foliage. I suspect that the plantations in Zambia could have survived drought without thinning if they were maintained with mild fire.

Best regards,

Vic

My Favourite Australian poet sums up our Eucalypts

Eucalypts in Exile

They’ve had so many jobs:

boiling African porridge. Being printed on.

Paving Paris, flying in her revolutions.

Supporting a stork’s nest in Spain.

Their suits are neater abroad,

of denser drape, unnibbled:

they’ve left their parasites at home.

They flower out of bullets

and, without any taproot,

draw water from way deep.

When they blow over

they reveal the black sun of that trick.

Standing round among shed limbs

and loose slabbings of bark

is homeland stuff

but fire is ingrained.

They explode the mansions of Malibu

because, to be eucalypts,

they have to shower sometime in Hell.

Their humans, meeting them abroad,

often grab and sniff their hands.

Loveable singly or unmarshalled

they are merciless in a gang.

—Les Murray

March 2010

I believe the words of Stephen Pyne are eloquent in their description of the “Universal Australian”

Eucalyptus is not only the universal Australian, it is the ideal Australian – versatile, tough, sardonic, contrary, self mocking, with a deceptive complexity amid the appearance of massive homogenity, an occupier of disturbed environments, a fire creature.