If you haven’t bought my book “Fires, Farms and Forests”, this book review on pages 17 and 18 of the Australian Forest History Society Newsletter Number 81 (December 2020) may inspire you to take the plunge. You can view the newsletter online at https://www.foresthistory.org.au/newsletters.html

NEW BOOKS AND PUBLICATIONS

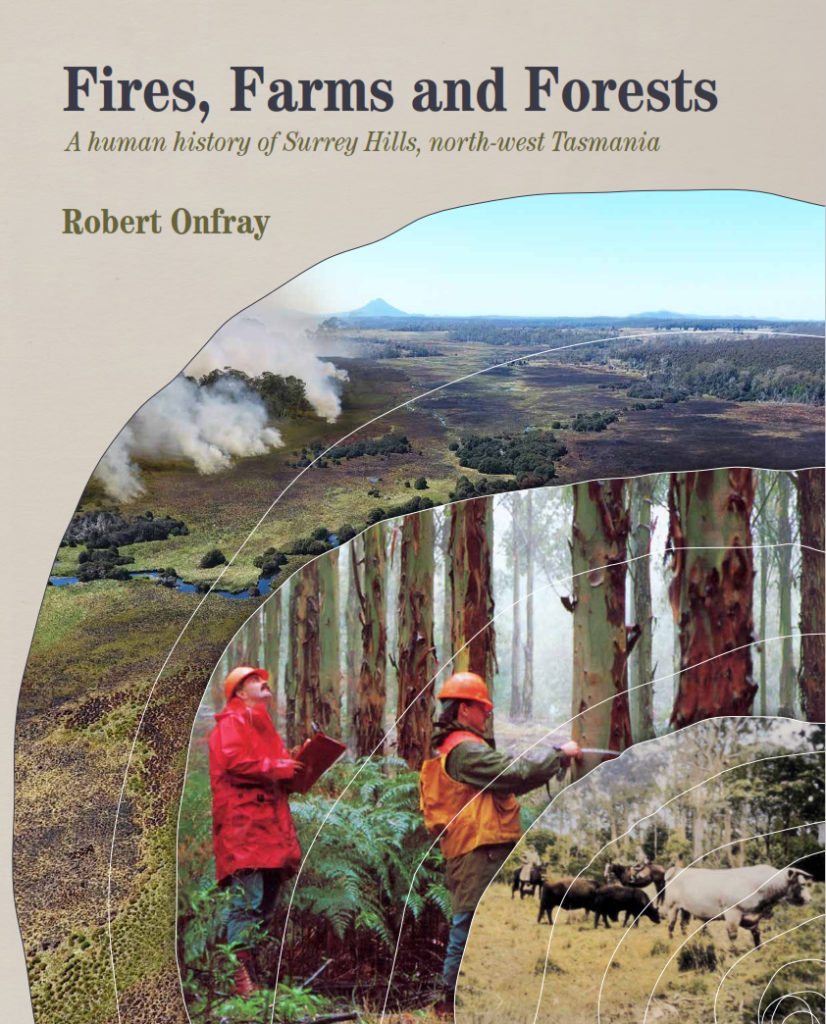

Robert Onfray, 2020. Fires, Farms and Forests. A human history of Surrey Hills, north-west Tasmania. Forty South, Lindisfarne, Tasmania. $55 + pp. ISBN 9780648675822.

www.robertonfray.com and https://tasmania-40-south.myshopify.com

A new book titled Fires, Farms and Forests by AFHS member, Robert Onfray provides a detailed environmental and cultural history of Surrey Hills and surrounding lands in north-west Tasmania. Members who attended the 2010 Lismore and 2015 Mount Gambier conferences would recall presentations Robert gave on this particular area.

Van Diemen’s Land was first settled in the south around Hobart in the early nineteenth century. The country supported open, grassy woodlands attractive to sheep farming. In the 1820s, one of two “private colonies” were established in Australia. The Van Diemen’s Land Company (VDL Co.) was granted 500,000 acres by an Act of Parliament in England. The grant had to be outside the established, settled areas in the north-west “beyond the ramparts”.

Surrey and Hampshire Hills were first named by the VDL Co’s Henry Hellyer in 1827 when he discovered native grasslands in a sea of rainforest. His sole purpose was to find suitable land to run Merino sheep to produce fine wool for the English market. The country he explored was different from the settled districts in the state’s southern and eastern parts. He had to bash his way through dense rainforests and horizontal scrub. When he stumbled onto Hampshire and Surrey Hills, he came across a broad plateau supporting large patches of open country. He described the grasslands he saw as those resembling “a neglected old park in England” with tall, straight trees “a hundred yards apart”.

Robert’s book, as the title suggests, covers three broad themes. The first theme on fires in the landscape recognises land management practices adopted by the original inhabitants of Tasmania. Robert worked at Surrey Hills for over 14 years as a professional forester. The diverse plant communities he encountered enthralled him. Initially, he struggled to understand why there was such botanical diversity in such a uniform landscape. Surrey Hills is situated on a broad, flat basaltic plateau. He soon realised that humans created the arbitrary boundaries of tall forests, rainforests, grassy woodlands, shrublands, native grasslands and moorlands. The landscape Hellyer discovered at Surrey Hills was, in fact, a cultural artefact – created by Aborigines through the use of fire.

There has been recent media coverage of Aboriginal management of the environment (see The Conversation ). This article referred to a study which focussed on Surrey Hills and provided evidence of changes in the landscape that have occurred after the removal of Aborigines. In his book, Robert delivers a fascinating account of the pre-European occupation of Surrey Hills drawing on ecological, botanical and archaeological studies in western and southern Tasmania. He eloquently provides a fascinating environmental history of the indigenous occupation from the last ice-age.

The farming theme focusses on the VDL Co. ownership of Surrey Hills. Robert spent 20 years reading copious folios of hand-written correspondence at the Burnie and Hobart libraries. The letters between the VDL Co.’s Court of Directors in London and the Chief Agents in Tasmania spanned over a hundred years. The European farming model introduced by the VDL Co. was immediately unsuccessful. The VDL Co. failed to establish Merino sheep farms on Surrey and Hampshire Hills. However, there is not much published information about how the VDL Co. managed the land over the ensuing 100 years.

His meticulous research outlines how the VDL Co. managed their grants, particularly at Surrey Hills, despite limited resources. The VDL Co. tried to attract farmers through a tenant system, even though there was limited access to Surrey Hills and no infrastructure apart from a few rudimentary huts. Their only option was to lease the land to the Field brothers, from near Deloraine, under a very strained relationship that remarkably lasted over 60 years. The Fields ran wild mobs of wild cattle looked after by bushmen living in the ramshackle huts initially built by the VDL Co. They did not “improve” the land in any way. They leased adjoining Crown land and didn’t require fences to control the cattle. The Fields paid a pittance for their runs, and despite several attempts by the VDL Co. to seek better terms, they couldn’t attract interest from other parties and were stuck with Fields who were flagrantly late with their payments. The Fields even managed to reduce their lease rate.

Despite constant calls on capital, a lack of dividends, and moves to wind up the company in the early 1850s, the VDL Co. managed to trade in timber and transport tin ore for the world’s largest tin mine, which kept the company economically viable.

December 1871 was significant in many ways for Tasmania. James “Philosopher” Smith discovered the world’s largest tin lode at Mount Bischoff that changed the fortunes of Tasmania and opened the way for further mineral discoveries in western Tasmania. In a cruel twist of fate, the discovery was located just outside the western boundary of Surrey Hills when the VDL Co. was desperate for other forms of revenue to keep afloat. London directors were keen to discover minerals on their land and employed prospectors to search their properties. Unfortunately, these prospectors lacked the temperament and bush skills of Smith. They were more prone to drinking than finding minerals of any worth.

William Robert Bell discovered silver on Hampshire Hills in 1875, and the VDL Co. desperately tried to mine the silver. The VDL Co. were cruelly led on by experienced geologists and miners who inspected the mine. Their reports were apocryphal, or at least not validated. After four unsuccessful attempts to discover an economical lode, the VDL Co. abandoned the mine in 1913. It is believed to be the oldest intact silver workings in Australia.

The Mount Bischoff discovery inspired the VDL Co. to build a wooden tramway through their Surrey and Hampshire Hills, and Emu Bay estates. They shipped the tin from the Emu Bay (Burnie) port, making their land at Emu Bay more valuable as the settlement expanded. The tramway was not cheap, and there were difficulties attracting labour for its construction. The tramway was finally completed in early 1878 covering a distance of 72 kilometres. Robert claims this is the longest wooden tramway built in the world. Remarkably, there has never been any recognition for its construction. The book’s detailed account of the tramway construction ensures this vital legacy is not forgotten, particularly as the tramway only lasted seven years before conversion to a railway.

The third theme on forests covers the exploitation of timber assets by the VDL Co. and subsequent owners. Surrey Hills supported large areas of Eucalyptus delegatensis forests and myrtle rainforest, which the VDL Co exploited to provide a diverse income stream. The Tasmanian timbers were highly valued in London, particularly blackwood for casks, joinery and general building purposes, but was in limited supply on their lands close to the Burnie port. The establishment of a sawmill in Burnie led to myrtle and E. delegatensis being transported via rail from Surrey Hills. The VDL Co. established a subsidiary company to harvest the timber in the extensive myrtle rainforest on the northern section of Surrey Hills, called Ringwood, before clearing for improved pasture to sell to farmers.

The establishment of the Burnie pulp and paper mill in the mid-1930s is closely related to Surrey Hills. Sir Gerald Mussen purchased Surrey Hills in 1924, to take advantage of the plentiful forests, water and deep port. It is an exciting story of one man’s perseverance to obtain funding for this significant industrial project during the Great Depression. Eventually, it led to a world-class, and Australia’s most significant, eucalypt plantation estate. Robert covers the boardroom machinations, and political power plays that led to the Tasmanian pulp and paper industry and Associated Pulp and Paper Mills (APPM).

The book is dedicated to APPM’s first forester, Reg Needham, who played a significant role in developing professional land management on Surrey Hills. Needham introduced many state-of-the-art and innovative forestry techniques. Because of a severe native forest regeneration problem, APPM began some experiments to trial the establishment of eucalypt plantations. A relatively small company had to discover what tree species could successfully survive on Surrey Hills and grow them commercially on a large scale. Robert provides a persuasive argument that Surrey Hills is the birth-place of industrial-scale eucalypt plantations in Australia.

Surrey Hills contains several plant and animal species of high conservation value. The book provides a fascinating and first-hand account of the management of these values, including the active use of fire to manage the native grasslands and moorlands. Robert doesn’t gloss over some of the failings and learnings experienced implementing cutting-edge techniques. The management of various environmental values is covered. These include the broader grasslands and moorlands, a rare orchid, butterfly species, attempts to control a destructive invader, the European wasp, and ground-breaking cancer research on the Tasmanian devil. Of particular interest is pilot translocation project to try and save the rare and endemic butterfly speices. Because of its unique environmental values, Surrey Hills has attracted paleoecologists, ecologists, and epidemiologists, all keen to study the dynamic processes in this unique landscape.

One interesting chapter is about Guildford Junction, the only enduring settlement on Surrey Hills. Low-pressure systems, which develop at any time in the Southern Ocean, travel uninterrupted until they reach the west coast of Tasmania. They provide plenty of cold and wet weather. These lows penetrate inland as far as the peneplain at Surrey Hills, receiving up to 2.2 metres of rainfall, 240 days of precipitation, and 120 frost events annually. It is a cold and harsh place to visit, let alone live. Guildford started as a railway camp in 1897 when the railway was extended to the west coast. Despite its short history of 87 years, the town supported some very dynamic and capable people who had to forge a life in a settlement so remote, that for most of its life, was only accessible by train. Fettlers, itinerant farmers, hunters, and timber workers, all with their families, lived at Guildford. At its height in the 1950s, the town supported over 80 residents. Apart from the houses, a primary school, a hall, a railway platform with a refreshment room and a licensed bar, there was not much else. It certainly was a lonely life for a housewife left at home while her husband worked in the cold, wet weather and the children attended school. It is now a forgotten ghost town.

One other little-known forest practice described in the book was snaring for animal fur to supply a worldwide market. During the first half of last century, runs were leased on Surrey Hills and experienced bushmen would spend up to three months in winter, during the open season, camped in rudimentary huts setting snares to catch wallabies and possums. Winter furs from the highlands and montane areas of Tasmania were highly prized. It led to the development of a unique system of drying the skins in a wet and cold environment, and there is an example of a drying hut on Surrey Hills.

Robert has brought to life the rich past of Surrey Hills by taking the reader on a journey of discovery. For anyone interested in human history and land management, it is well worth a read.

You can also view his blog site that provides additional stories not covered in any detail in the book https://www.robertonfray.com/category/surrey-hills/