From gold to heavy minerals

The story of Australian sand mining spans over more than a century, beginning not with industry, but with the pursuit of gold. In the late 1800s, small groups of miners panned the black beach sands along Australia’s east coast, from Bermagui in New South Wales to Fraser Island in Queensland, searching for a few shimmering specks.

At Ballina, on the Richmond River, John Sinclair (no relation to the later environmentalist activist of the same name) discovered gold in the black sands in 1872, sparking minor rushes along beaches to the north. The yields were small, averaging only eight grams per week per person. However, during the economic depression of the 1890s, beach mining provided a crucial income for unemployed labourers.

By the early twentieth century, scientific curiosity had shifted from gold to the dense, metallic-looking minerals that coloured those sands black. Among them were ilmenite, rutile and zircon, minerals that would soon underpin global industries.

The rise of the mineral sands industry

Initial attempts to extract these “black sands” took place near Jerusalem Creek and Black Head, close to Ballina, in the 1920s. The minerals were sent to Britain for testing, but the ventures failed, mainly because the amounts were small, and the refining technology was basic.

By the 1930s, however, advances in separation techniques across North America revolutionised the industry. The coastal sands of New South Wales produced the first commercial supplies of rutile and zircon, particularly around Byron Bay, establishing Australia as a global leader in the production of heavy mineral sands.

Ilmenite, when refined, produces titanium dioxide, a bright white pigment used in paints, plastics, and cosmetics. Rutile, a purer form of the same oxide, was sought for both its pigment properties and as a feedstock for metallic titanium, valued for its strength and resistance to corrosion. Zircon became essential in refractory linings, foundries, ceramics, and later in nuclear technology.

During World War II, atomic energy was a major focus. Within the heavy minerals, there was a known but very small amount of monazite – a source of cerium and thorium, fissionable elements seen as a potential source of atomic power. The Bureau of Mineral Resources was tasked with assessing the distribution of monazite within the beach sand deposits between Southport in southern Queensland and the Clarence River on the north coast of New South Wales. Their work, published in 1955, also determined the reserves of zircon, ilmenite, and rutile.

During the Cold War, titanium’s strategic importance soared. The United States required large amounts for aircraft and spacecraft manufacturing. As global demand increased, focus shifted to Queensland’s extensive coastal dunes.

The move north to Fraser Island

By the late 1950s, deposits in northern New South Wales were running low. Exploration crews started sampling the dunes of Stradbroke Island, Cooloola and Fraser Island. Geological surveys confirmed thick layers of heavy mineral sands along Fraser’s eastern beaches and Rainbow Beach.

In 1957, the Rutile Corporation of Australia proposed a £1 million-a-year operation on the island, and soon two American-backed companies – Dillingham Corporation of Hawaii, through its subsidiary Murphyores Holdings (Australia) Ltd, and Queensland Titanium Mines (QTM) – secured leases. Processing plants were built south of Eurong, and dredges extracted the mineral concentrate from behind the frontal dunes, returning the remaining sand to the landscape.

QTM moved its main dredge from Inskip Point across the Great Sandy Strait onto the island in December 1971 and started sand mining the next month. They mostly operated along a 17-kilometre stretch of foredune no wider than a few hundred metres from the Dilli Village track to the beach.

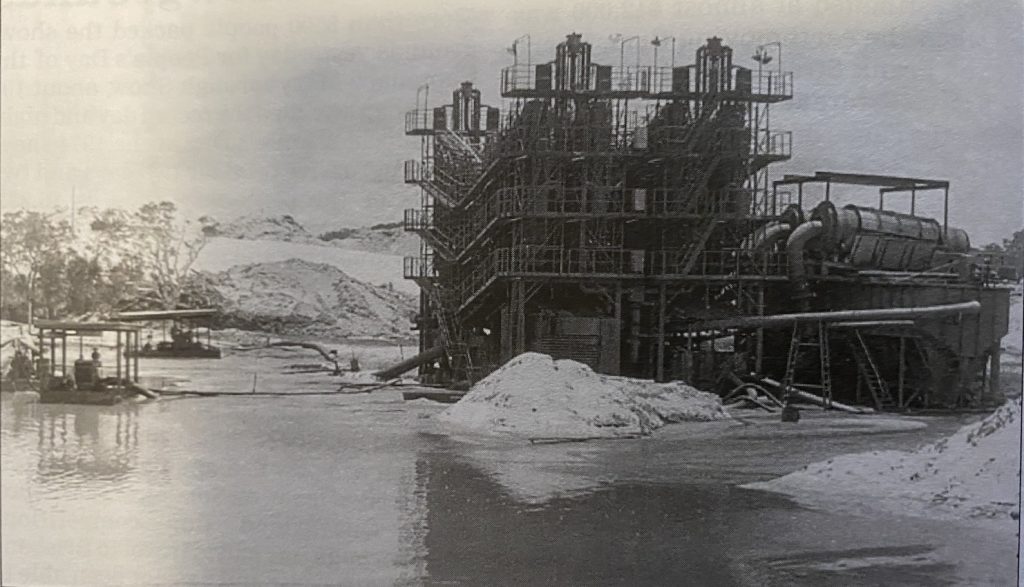

They used a “wet” mining process, which involved the processing plant separating the heavy mineral sand from the siliceous sand in the same pond as the cutter head.

When mineral sand deposits were discovered in the back dunes behind the beaches, mining methods changed. Ponds were dug, and small floating dredges were used to extract the minerals.

In contrast, Murphyores was a much larger operation than QTM, operating at about five times the pace. They didn’t actually start mining until May 1975, as they prepared and built much more extensive infrastructure to support their operation. They worked south-west of Dilli Village, away from the foredunes, using a “dry” method, although it still involved a cutter head operating in a pond. The primary separation plant wasn’t floating in the pond. It was located further away.

The sand was pumped to it from as far as a kilometre away. A large Allis-Chalmers bulldozer worked in conjunction with the cutter head to keep the sand feeding into the much smaller pond. They trucked the treated product along Dillinghams Road to Buff Creek, where it was barged to Maryborough for secondary separation.

Although large machinery was used for the work, the extent of disturbance remained modest. By May 1975, only 390 acres had been mined (less than 0.2 per cent of the island), and production included 44,292 tonnes of rutile and 32,793 tonnes of zircon. Rehabilitation trials indicated that vegetation recovered quickly.

For the local economy, the mines were a lifeline. The Maryborough district, already struggling from the collapse of its dairy industry and the closure of Walker’s Shipyards, regarded sand mining as a crucial new source of jobs and export income.

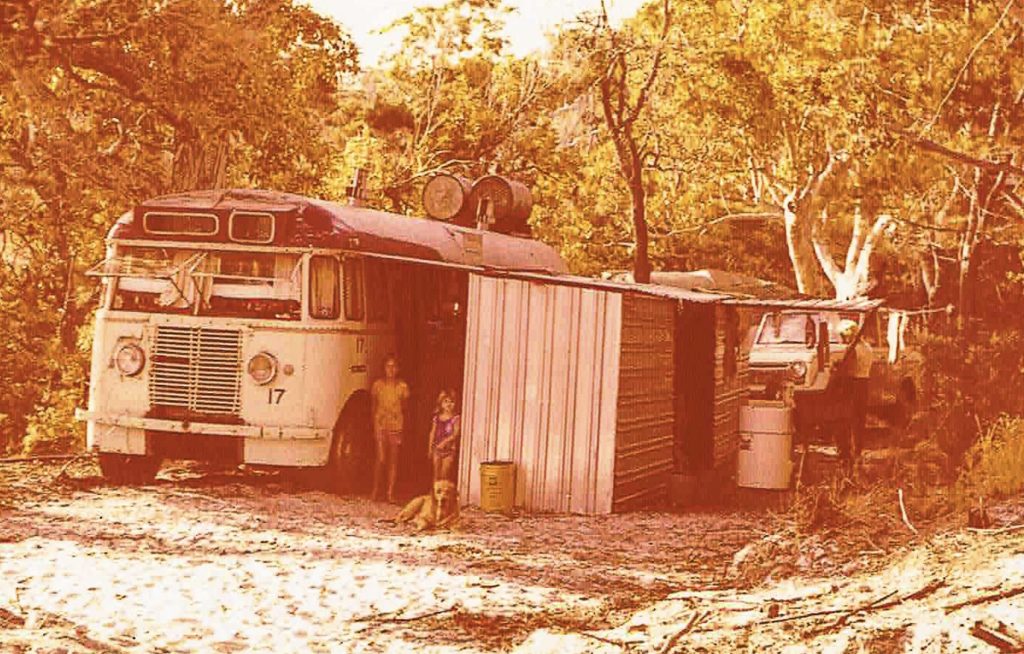

For 10-year-old David Postan, whose family operated a logging contract business on the island, this period was unforgettable. His father, Andrew Postan, constructed Dillinghams Road across Fraser Island for the sand miners. While doing this, the family camped on the shores of Lake Boemingen, a child’s wondrous playground. They even had a seaplane land on the lake while we were there.

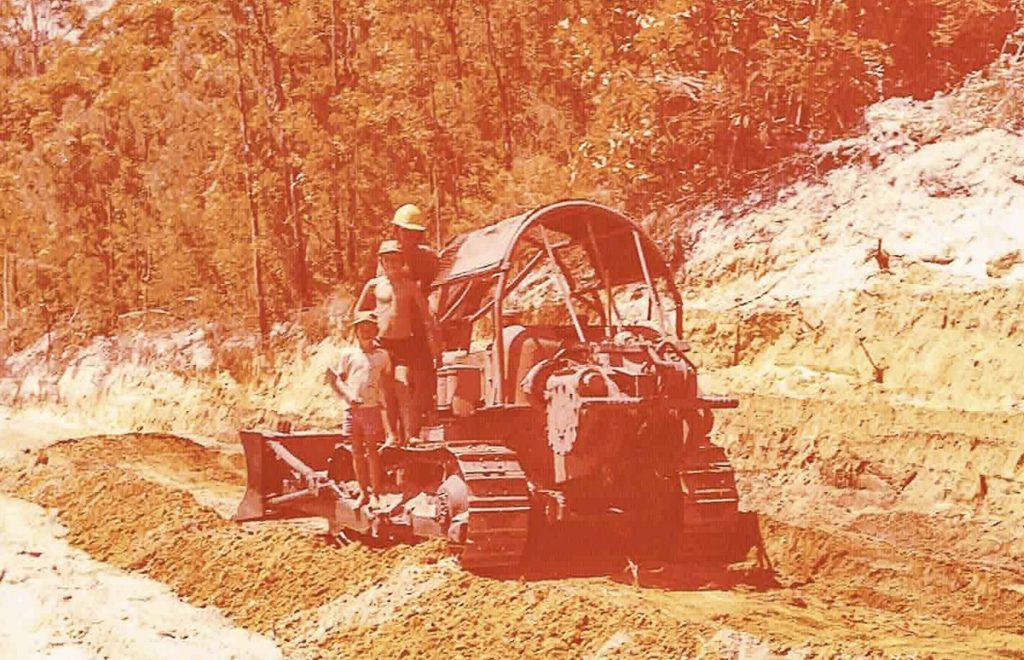

The airstrip, known as Toby’s Gap, was off Dillinghams Road. It was a bustling spot when the mine was operational and under construction. The largest dozers of the time, Allis-Chalmers HD-41s, arrived on the island. They were powered by a VT1710 Cummins twin-turbo V12 engine, producing 524 HP, with blades up to 20 ft wide and weighing around 80 tonnes.

Young David had an unforgettable experience driving one of the dozers during road construction – any boy’s dream.

The political climate of the 1970s

By the early 1970s, environmental awareness had started to grow worldwide. The newly established Fraser Island Defenders Organisation (FIDO), led by John Sinclair, a Maryborough adult education teacher and activist, focused on Fraser Island as a cause célèbre. Sinclair’s campaign aligned with the rise of environmental politics in Australia and a federal government eager to extend its influence over resource management, a state responsibility.

Sinclair depicted Fraser Island’s sand mining as an environmental disaster. Through the FIDO newsletter, Moonbi, he used emotive language and grim predictions about damage to lakes, forests, and dune systems. However, few of these claims were backed by scientific research. The total area mined was small, and hydrological and vegetation monitoring showed no significant or lasting damage.

Nevertheless, the campaign managed to capture the public’s imagination. The media, eager for stories of “David versus Goliath,” portrayed Murphyores as a foreign industrial villain and Sinclair as the heroic protector of the environment.

In 1974, the Whitlam Government, which had recently established the Department of the Environment, aimed to test its new Environment Protection (Impact of Proposals) Act 1974. Murphyores’ export-driven operation served as the ideal vehicle for asserting Commonwealth authority over a resource project approved by the State.

The inquiry and the court challenge

When the Commonwealth announced an environmental inquiry into Fraser Island mining in 1975, both the Queensland Government and Murphyores declined to participate, viewing the process as politically motivated. Their absence left the field to environmental academics and activists whose submissions, untested by counter-evidence, portrayed the impacts as catastrophic

The inquiry concluded that mining “probably” posed risks to lakes and creeks, although its findings were based on studies conducted elsewhere. It recommended that sand mining cease. Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen strongly rejected these claims. In a letter to Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, he enclosed hydrological studies showing:

No immediate or long-term effects on surface or groundwater.

And noted that:

Rehabilitated dunes reacted to fluctuations in plant nutrient levels at the same rate as unmined control areas.

Despite such evidence, the High Court case Murphyores Inc Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1976) upheld the federal government’s constitutional power to control exports on environmental grounds. This ruling effectively granted Canberra veto authority over projects that were previously within State jurisdiction.

John Sinclair and the World Heritage debate

Following the court case, Sinclair continued his campaign, extending it to include World Heritage listing. After the Whitlam Government ratified the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1975, Sinclair made an extraordinary claim in Moonbi:

It is worth noting that because it is an International Treaty, the Australian Government gains the constitutional powers to overrule a State Government, if necessary, in the management of the parts of the world heritage. Therefore, if Fraser Island is included in the World Heritage List, the Australian Government would have an inescapable obligation which would override the decisions of the Queensland Government.

This was a deliberate misrepresentation. The Commonwealth Department of the Environment was compelled to issue a clarification, reassuring Queensland that World Heritage listing did not transfer administrative authority to the federal level. The Queensland Solicitor-General also dismissed Sinclair’s assertion as baseless.

Such tactics demonstrated a pattern in Sinclair’s approach, indicating that effective public relations relied more on political influence than on scientific precision.

A decision driven by politics

On 10 November 1976, Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser announced that his government would accept the inquiry’s recommendations. On 31 December, the export of mineral sands from Fraser Island was limited to already-mined stockpiles. This effectively shut down the sand mining operations on the island.

The decision was made quickly. Parliament spent only 25 minutes debating the report before voting. Just three weeks after banning Fraser Island exports, the government issued new export licences for other mining operations, highlighting the selective nature of its environmental concern.

For the workers of Maryborough and the mining companies, the impact was immediate and severe. Most miners received six weeks’ notice and faced Christmas without jobs. Compensation was minimal, and community anger ran deep. To many Queenslanders, the decision confirmed what Bjelke-Petersen described as:

A blatant exercise in federal political opportunism disguised as environmental policy.

The following year, Fraser Island became the first site listed on the Interim Register of the National Estate by the new Australian Heritage Commission. It was a symbolic act that marked the beginning of Commonwealth involvement in land management in Australia.

Rehabilitation and regrowth

After mining, QTM rehabilitated and revegetated the area behind the dredge that had been backfilled. It levelled and battered towards the adjoining unmined area. The most exposed part of the frontal dune was covered with brush matting, and coastal she-oaks were planted. The more protected rear sections of the foredune were covered with stockpiled topsoil, which contained seed from native vegetation, mainly wattles. Some supplementary planting also took place.

Murphyores reshaped the mined areas to mirror their original contours. In addition to plantings, seed from nearby unmined areas helped germinate in the disturbed zones and grew into reasonably sized trees. After spreading the topsoil back, the area was mulched and sown with a crop of hybrid sorghum that didn’t produce viable seed, helping to stabilise the area and protect the germinating seeds in the topsoil. Native plants grown at a nursery near Dilli Village were also manually planted.

After the dredges fell silent, the mined areas on Fraser Island started to recover. By the late 1980s, observers saw widespread natural revegetation and few signs of earlier operations. Former workers, returning to their old sites, were often surprised by how resilient the landscape was.

Subsequent ecological studies confirmed the consultants’ original findings of no significant hydrological changes to the island’s freshwater systems, and nutrient cycling in rehabilitated dunes reflected that of unmined areas. Evidence and visual observations indicated that while a sand mining site may never be restored to its original state, it has been successfully rehabilitated into native bushland that existed beforehand, featuring diverse native flora and fauna. Studies have shown that recolonisation by small mammals occurred in a pattern similar to that following a fire.

Yet these facts arrived too late to shape the public narrative. The environmental win had already been mythologised, and the broader political story had been forgotten.

Reassessing the “environmental” battle

Looking back, the Fraser Island sand mining controversy was never mainly about the environment. It was about power, particularly the struggle between the Commonwealth and Queensland over control of resources, set against the backdrop of a growing environmental awareness.

The Federal Government used the case to establish its environmental credentials and legal authority over exports. The activists, notably Sinclair, used it to galvanise public opinion and elevate their cause, and the media used it to tell a compelling morality tale.

The actual environmental impact of sand mining was minor, localised and mostly reversible. However, perception held more weight than evidence. Consequently, a legitimate and well-managed industry was sacrificed for politics, and a struggling regional community bore the burden.

Concluding remarks

Today, Fraser Island is a World Heritage site renowned for its natural beauty. Few visitors realise that the end of mining was more due to Canberra’s assertion of constitutional authority than ecological necessity.

The 1976 decision marks a crucial point in Australian resource politics. It was when environmentalism became a tool of national policy, and public perception started to overshadow scientific advice in managing natural resources. Nearly twenty years later, the forestry profession realised this as they were scapegoated during the battle to preserve Fraser Island as a museum piece, only to see unchecked tourism cause far greater environmental issues than forestry and sand mining combined.

The Fraser Island sand mining saga remains a reminder of how political ambition, media influence and selective truth can turn a small industrial operation into a national icon for all the wrong reasons, shaping environmental politics for generations to come.