A routine tour turns to disaster

On the morning of Wednesday, July 22, 1970, Jack and Eileen Reville were going about a typical day at their successful Fraser Island tourism business. They readied their tour boat, the Island Queen, for a scenic outing with 46 tourists — mainly elderly holidaymakers — to the island.

It was a lovely, sunny, typical winter day. After gathering the passengers’ tickets and directing them to their seats as they boarded the boat, Eileen departed to head home.

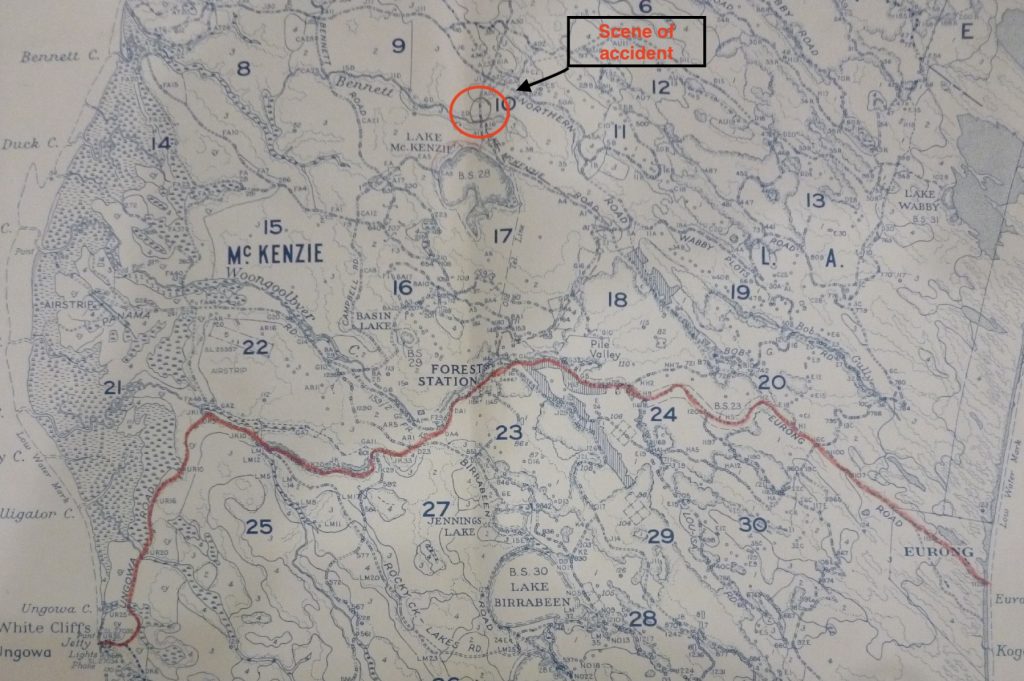

The Island Queen left Urangan’s T-jetty at 7:55 am, crossing the Great Sandy Strait to McKenzie’s Beach near the old jetty. Upon arrival, about two hours later, passengers were ferried to shore via an aluminium punt, where two vehicles awaited them: a converted 1940s Chevrolet Lend-Lease blitz flat-top truck, owned and driven by Reville, and a panel van driven by Sid Melksham, who had been called in to assist with the overflow of tourists.

Reville was a pioneer of using tour buses on Fraser Island. The year before, he began offering travel in a larger vehicle to accommodate more people. He modified the Blitz to fit 38 passengers across eight rows of padded seats by extending the truck’s rear by nearly two feet and installing a galvanised iron piping canopy frame over the wooden tray. Eight passengers boarded Melksham’s van, while the others took seats in Reville’s truck.

The tour group set off for the back beach at Eurong, arriving around noon to enjoy lunch. Shortly after 1 pm, Reville’s truck departed for quick stops at Central Station and Lake McKenzie before returning to McKenzie’s jetty. Melksham attended to some business needs while at Eurong and followed about ten minutes later.

That was when disaster struck.

A deadly descent

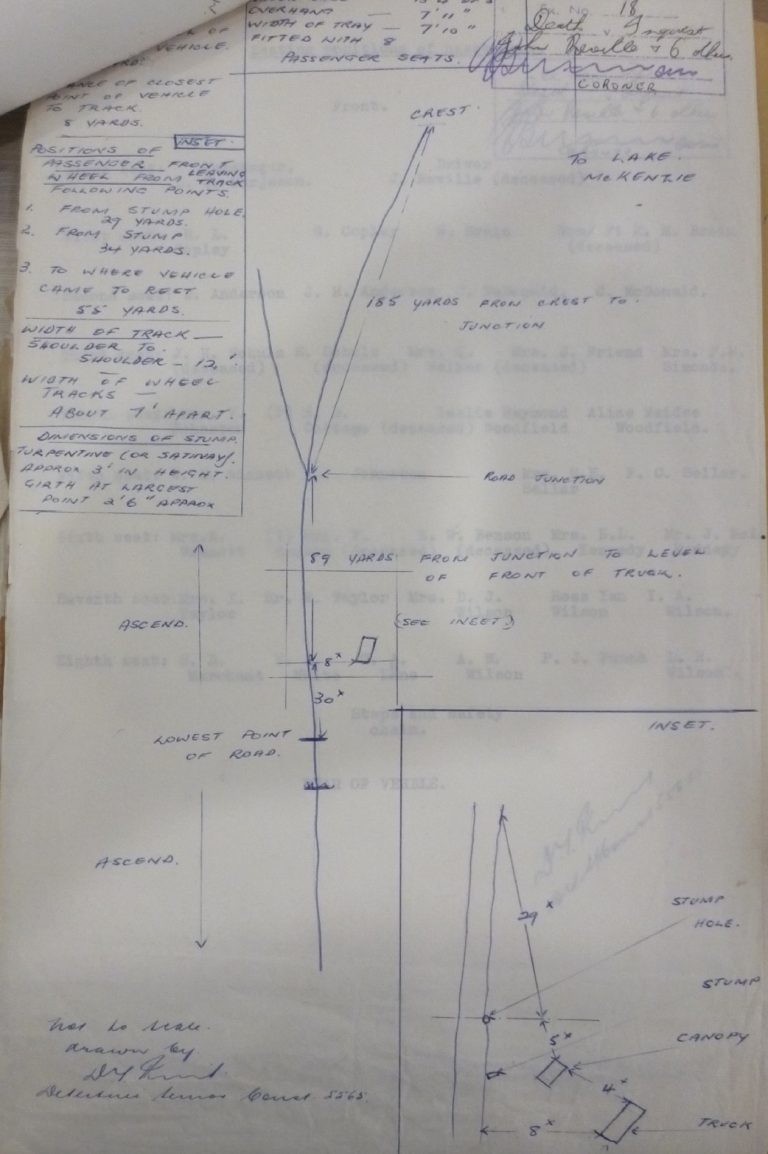

Shortly after leaving Lake McKenzie, Reville’s truck reached the crest of Lake McKenzie Road, part of the Northern Road, before the track dropped steeply. It was about 2:25 pm. For approximately 100 metres, the grade was 20 per cent, or one in five.

Reville tried to engage low gear but was unsuccessful. He attempted this three times, yet the gears refused to engage. After cresting the hill, the truck, now in neutral, quickly picked up speed.

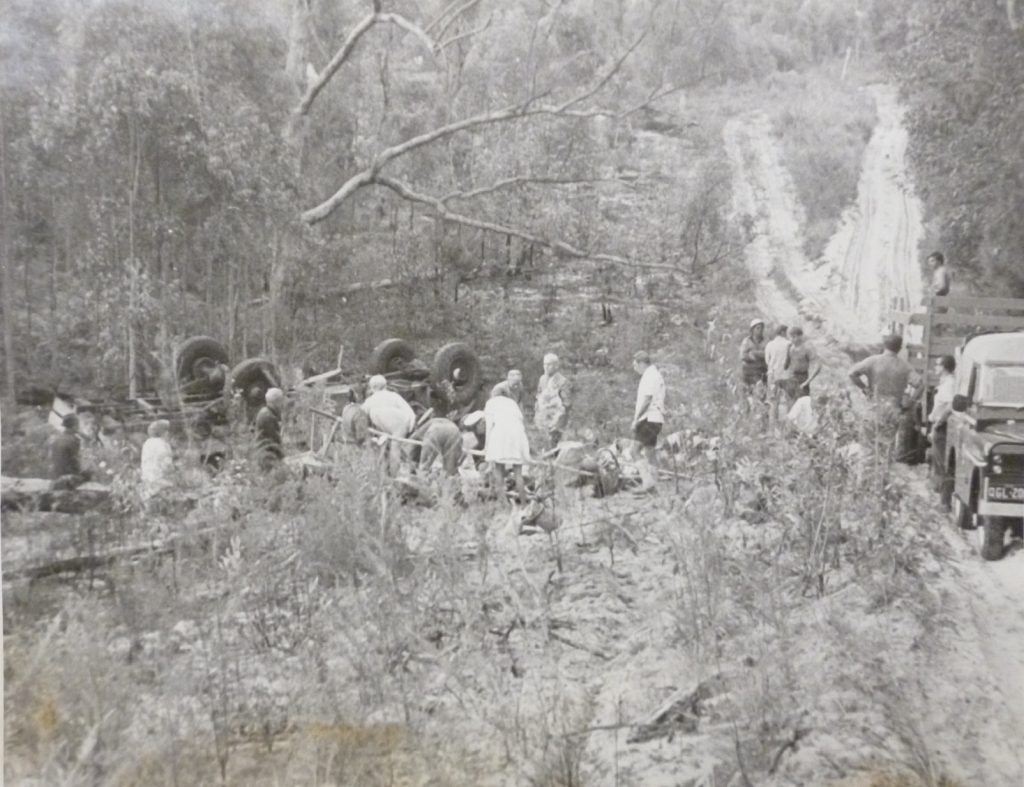

Surviving passengers later recalled how the truck swayed uncontrollably as it plummeted down the slope. Near the bottom, Reville lost control. The vehicle veered left and right before smashing into a tree stump with such force that the stump was ripped from the ground. The impact flipped the truck, and most of the passengers were hurled from their seats as the canopy frame was torn away. The vehicle rolled and came to rest on its roof. Most passengers landed on top of or near the crumpled canopy after it wrapped around a tree.

One survivor estimated the truck was travelling at 50 miles per hour when it left the track.

The rescue effort

Trailing behind, Melksham was stopped by a frantic passenger running up the track to give a chilling message. The truck had lost a gear and crashed. Rushing to the scene, Melksham arrived to find utter devastation. Bodies were sprawled around the wreckage near the overturned truck. He quickly counted at least four or five dead, with many others seriously injured.

Recognising the seriousness of the situation, he asked his male passengers to remain at the scene and offer any assistance they could, even though none of them had any medical or first aid knowledge. He quickly drove to Central Station to inform forestry workers, asking them to seek help from the mainland and to bring supplies such as blankets and lamps, knowing the site would be in darkness by the time help arrived.

Worried that official responders might not reach the island in time, Melksham took the initiative to arrange swift action. He contacted Don Adams, a local charter pilot and owner of Island Airways based at Scarness, requesting urgent medical aid.

Adams sent a plane carrying a police officer, Dr Arthur Mayne and the matron from the Hervey Bay hospital to Fraser Island’s Woongoolbver airstrip as quickly as possible. Melksham set out flares to mark the landing site, and by 4:05 pm, the plane arrived. Melksham hurried them to the accident scene, arriving at 4:45 pm.

Dr Mayne confirmed six fatalities upon arrival, with another victim succumbing to their injuries shortly thereafter. As he stabilised the survivors, Melksham and forestry workers transported 19 seriously injured passengers to the airstrip in multiple trips. Throughout the evening, Island Airways and another two light planes from the Bundaberg Aero Club made five emergency flights, ferrying the wounded to hospitals in Maryborough and Hervey Bay with special permission from the Department of Civil Aviation to fly and land at night.

The first flights, carrying 12 walking injured, were taken to Hervey Bay Hospital. Another flight, carrying five stretcher cases and five walking wounded, was taken to Maryborough Airport, where the patients were admitted to Maryborough Hospital. Another six injured were taken to River Heads by the Forestry vessel. A further ten people were flown to the Maryborough airport in three other flights.

On the mainland, before flying to the island, Dr Mayne requested a helicopter to evacuate the seriously injured and avoid a lengthy road trip. Unfortunately, efforts to secure an Army helicopter in the local area were unsuccessful before nightfall.

A grim night on the island

By 9:30 pm, all survivors had been evacuated via the forestry launch Karowinga. The bodies of the deceased, however, remained. It was late, and the police decided to leave the bodies on the island until the morning. Forestry workers, and volunteers, including Melksham and local logging contractors, assisted police in moving them to an abandoned logger’s hut a mile away — an eerie makeshift morgue to protect them from dingoes overnight. The hut later became known as “the Morgue.”

At dawn, the recovery effort resumed. Belongings were gathered, and the bodies were loaded onto Melksham’s GMC truck for transport to McKenzie’s jetty. From there, the bodies were loaded onto the Island Queen, which Melksham piloted back to Urangan, where ambulances were waiting.

The investigation: a deadly oversight

The subsequent coronial inquiry revealed shocking findings about the truck’s condition. A vehicle inspector from Maryborough discovered that Reville’s truck had no working brakes. The front brakes were disconnected, and sand accumulation in the rear brake drums indicated they had been non-functional for some time. Even worse, the master cylinder was dry, corroded, and filled with sand — proof that the brake system had been inoperative for a significant period.

He believed that Reville didn’t select a lower gear at the top of the hill, which was tricky in that type of vehicle while moving. Without brakes, Reville could do little to control the truck; he could only try to ride out the steep descent.

The inspector concluded that the main factor in the accident was the lack of oil to operate the brake system. At the coronial inquiry, one of the passengers was asked if he knew the truck was fitted with brakes. He testified that they encountered another vehicle coming from the opposite direction on their way to the back beach. Reville steered the truck into the loose sand on the roadside to bring it to a halt. He believed the brakes were never applied at any time.

The Inspector also acknowledged that he had inspected the truck seven months prior and deemed the brake system “satisfactory” and the truck roadworthy.

Melksham informed the inquiry that Reville had difficulty changing gears because he didn’t use double de-clutching, which was necessary for the truck’s gearbox type. He also mentioned speaking with Reville at Eurong on the day of the accident about the steep hill leaving Lake McKenzie. After Melksham cautioned him that it was a risky hill and advised him to be extremely careful, Reville replied:

At least it’s straight and if anything goes wrong you can just ride it out to the bottom.

Sadly, lacking gears or brakes, he had no control over the truck’s deadly plunge.

Fallout and lasting changes

The accident had a profound impact on the island’s emerging tourist industry. It was found that Reville’s truck was neither insured nor registered. This wasn’t particularly surprising, as all vehicles on the island were unregistered since none of the roads were classified as public.

Eileen Reville disclosed at the coronial inquiry that they failed to arrange third-party insurance, which turned out to be costly.

The accident sent shockwaves through the fledgling Fraser Island tourism industry. The Queensland government, embarrassed by the absence of oversight, commissioned a review of vehicle conditions on the island. Inspectors discovered widespread mechanical neglect, especially in tourist vehicles, which often lacked proper brakes or steering. Although directives were issued for compliance with traffic regulations, enforcement remained lax.

Embarrassed by the incident, the government promptly called for a review by the Department of Transport. It remained somewhat unclear whether the roads on the island were public. In any case, the truck’s registration status did not influence the prevention of the accident.

An inspector from the Department of Transport was sent to the island to prepare a report on transport operations in general. He quickly realised that, as it is a sand island, the roads were merely bush tracks that do not meet any conventional standards for the safe passage of vehicles. He noted that vehicles on the island were in poor condition, with many operating without brakes. After observing a similar blitz tourist truck, he believed:

That the seating accommodation and the mechanical condition in so far as braking and steering are concerned, is unsatisfactory.

As a result, all vehicles were inspected, and orders were issued to comply with the requirements of the Traffic Regulations. However, it remains unclear whether any follow-up inspections were conducted to ensure that the necessary work was performed and that vehicles were maintained to a high standard, despite the challenging conditions faced by owners of vehicles permanently stationed on the island.

Following the tragedy, the Maryborough and District Tourism Bureau advocated for the construction of proper roads, a jetty for passenger offloading, and enhanced emergency infrastructure. Meanwhile, Dr Mayne suggested establishing a permanent first-aid station stocked with essential supplies and a two-way radio for communication across the island.

The forgotten victims

Eileen Reville, left to bear the financial and emotional burden of the tragedy, was forced to sell the Island Queen and their home. Victims’ families sued her for compensation for funeral expenses and damages. Eventually, the government intervened, settling claims under the Motor Vehicles Insurance Act, which covered unregistered vehicle accidents.

Amid the media storm, headlines screamed “200-yard terror plunges” and “7 die in bush crash.” In response, Eileen penned a heartfelt letter to the newspaper, expressing her deep sorrow and gratitude to those who defended her husband’s name. She ended simply:

May God help and bless those of you who are left to suffer.

A Warning ignored

Disturbingly, the crash was not the first warning of danger. Just seven months earlier, another of Reville’s tourist buses, carrying 50 passengers, overturned while trying to negotiate a steep decline not far from the fatal crash site, injuring several passengers. The passengers submitted a report to the Burrum Shire Council detailing the poor vehicle conditions and lack of safety equipment, but the council dismissed the unsigned report. When they sought a re-submission of the report as signed, most passengers had left the region, and the warning was lost.

One of the passengers later recalled that Reville admitted the bus had neither hand nor foot brakes, stating that:

they deteriorate too quickly in salty and sandy conditions.

Legacy of a tragedy

The Fraser Island bus crash of 1970 stands as one of the darkest days in the island’s history. While it sparked discussions about safety, enforcement remained inconsistent, and the risks associated with makeshift tourism operations continued for years. This tragedy serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of poor vehicle maintenance and insufficient oversight in remote tourism ventures.

For the Reville family, the pain of that day never faded. While history has recorded the loss of seven lives, including their husband, father and grandfather, their own suffering, the financial ruin, the public scrutiny, and the haunting weight of what transpired, remains largely overlooked.

Postscript

According to reports, a small memorial was erected at the crash site on the side of the road. However, anyone keen on visiting the site will be disappointed. It is impossible to find.

As you can see in the photos and as described in Chapter 15 of my upcoming book, the section of that road down the steep hill was originally built as two parallel firebreaks, each 12 feet wide, that were cleared, grubbed, and harrowed. The one chain strip in between was brushed and burned. They effectively aided in planned, prescribed burns, or back burns during wildfires.

That road is now closed and forms part of the Great Walk Track. The wide clearing is overgrown, and, as shown in the photo below, it is ineffective in stopping or fighting fires.

That is part of why we have a fire problem on the island under the current managers.

Well researched as usual.

Hello

As a modern day tour guide to the island, out of Brisbane I’m intrigued by this event.

Heading up next month on a personal tour with first timers …determined…

I’ll find the memorial if it’s actually there ..

Good luck looking for it, Gordon. I have tried. The area is pitifully overgrown, and the lack of respect shown by current managers is deplorable. If you work for Kingfisher, I suggest you speak with managers there and ask them to help find it and maintain it, out of respect for those who lost their lives that day. Because, sure as hell, the bureaucrats don’t care.