This story explores the transformation of the humble Australian tea tree (Melaleuca spp.), which thrives in swampy areas, into an essential oil and other various health care products sold globally.

The burgeoning tea tree industry began in a remote, swampy area of the Richmond River Valley district in northern New South Wales. The oil from the medicinal Melaleuca alternifolia, or feathery tea tree, launched the fledgling industry. While there are over 300 species of tea tree—the collective common name for two allied genera, Melaleuca and Leptospermum—most of which produce essential oils and exhibit some healing properties, the oil from the feathery tea tree was found to be far superior in many aspects and is the predominant one used to make tea tree oil. A comparable oil can be obtained from M. linariifolia (paperbark tea tree) and M. dissitiflora (creek tea tree).

From ancient knowledge to colonial curiosity to discovery

Long before scientists and entrepreneurs took notice, the Bundjalung people of northern New South Wales harnessed the tea tree’s healing powers. They crushed the leaves into poultices to treat wounds and infections—an ancient bush remedy drawn from generations of observation.

Fast forward to 1770, when Sir Joseph Banks, botanist aboard Lieutenant James Cook’s Endeavour, first documented the tree. Cook’s crew brewed a refreshing tea from the aromatic leaves, earning it the nickname “tea tree”. They also noted its antiseptic properties, which were later confirmed by their ship’s doctor. Cook and his crew drank the tea to prevent scurvy.

In the 1920s, chemist Arthur Penfold from the Technological Museum in Sydney (now the Powerhouse Museum) began analysing Australian native oils for their commercial and medicinal potential. He initiated tests of various plant oils as germicides and therapeutic agents.

In 1925, he announced to the Royal Society of New South Wales the results of a three-year study showing that oil from the feathery tea tree had a very high potential as an antiseptic. It was 11 to 13 times stronger than carbolic acid yet had none of that standard antiseptic’s burning or caustic properties. Further research on tea tree oil progressed, and papers published worldwide reported excellent results using the oil for throat, mouth, dental and gynaecological conditions, as well as treating septic wounds and various skin fungi. Scientists of the day proclaimed that tea tree oil was the finest natural antiseptic known to science.

Tea tree oil is a complex oil that contains nearly 100 components working together to produce its healing power. This spicy aromatic oil ranges from clear to pale lemon in colour and has a milder, less pungent scent than eucalyptus oil. It is the first natural substance known to contain the compound viridiflorene, which possesses antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties.

The first boom

Penfold’s research sparked a rush to harvest feathery tea trees. The epicentre was the Bungawalbyn swamp, near Coraki in northern New South Wales, where oil-rich trees grew in dense, flood-prone country.

Australian Essential Oils (AEO) was established in 1927 to pioneer the harvesting of feathery tea trees in their natural state. Gangs of cutters armed with machetes worked through the Depression years. It was hard, muddy work, but it offered employment when jobs were scarce.

AEO set up a small distillery to extract oil from the leaves, which was then shipped to Sydney from Coraki. Men held branches upside down in one hand and slashed off all the little branchlets onto a two-metre square of hessian. Once a sizable heap about one foot thick was gathered, the diagonally opposite corners were tied to form a bag, and the leaves were taken to the still for processing. Each bag weighed about 60 to 80 pounds, and a good cutter could strip nearly one tonne a day.

While tea tree can be harvested year-round, except during flowering, higher yields and better quality are obtained from spring flowering until the following June. AEO had a boiler at its distillery that supplied steam to three distilling pots. The steam passed through the leaves and burst the capillaries on each leaf, releasing oil vapour from the tiny glands. The steam and oil vapour passed through a metal coil immersed in cold water, called a condenser. The condensed liquid was passed through a collection tank, where the oil floated, and then siphoned off, filtered, and stored in casks.

The cooked leaves were removed from the pot and placed nearby. As soon as they were dry, they were burned, and the ash was used as fertiliser.

In the Coraki district, dairy farmers aiming to clear and drain as much land as possible found it challenging to remove feathery tea trees unless they dug out each individual tree, as these trees tended to coppice after being cut down. However, this characteristic benefited those harvesting the tea tree, allowing annual harvesting and regrowth.

In addition to AEO, numerous smaller companies operated in the swampy regions of the Richmond and Clarence Valleys, where feathery tea trees were abundant. As many as 40 stills were in operation during the Depression.

Soaps and setbacks

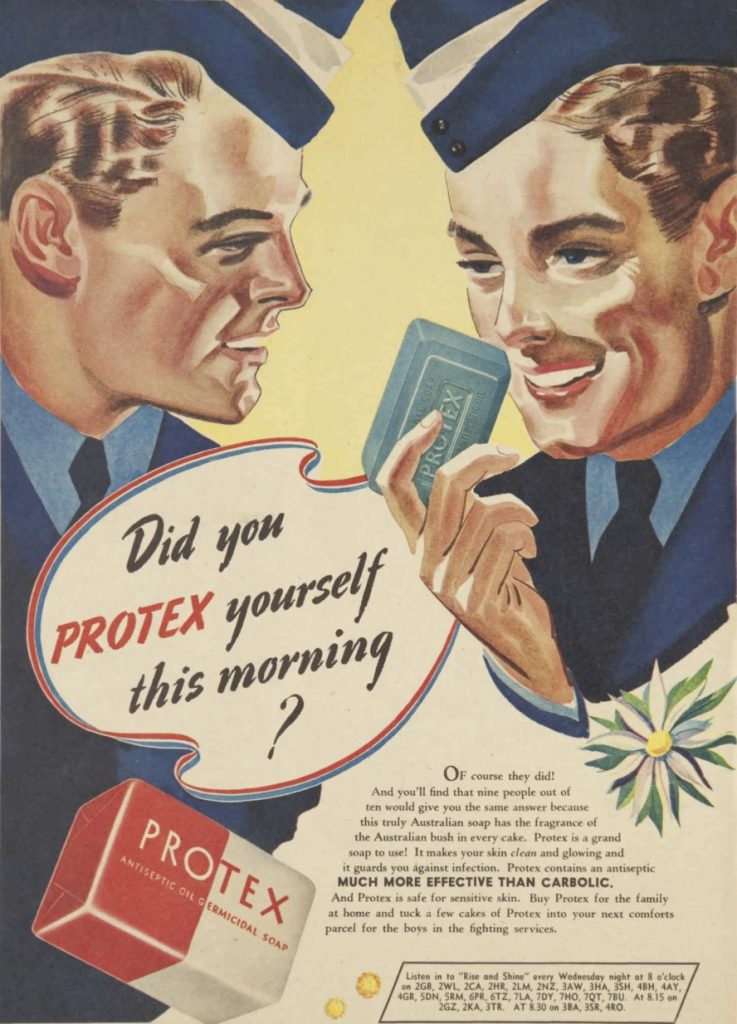

By the 1930s, tea tree oil had made it into Australian homes—its most famous appearance in Protex germicidal soap with the catchy line, “Did you Protex yourself this morning?” Yet even with growing demand, supply couldn’t keep up. A major contract with the American arm of Colgate-Palmolive was lost due to limited oil volumes.

The parent company in America wanted to produce the soap for its massive market. However, instead of supplying the required hundreds of tonnes of oil, only tens of tonnes could be delivered, and the opportunity was lost. Over time, the Australian company shifted away from using tea tree oil as fashion trends shifted towards a preference for perfume soaps over germicidal soaps.

This example showed just how unstable the tea tree oil industry was. It was affected by tough working conditions, weather and fluctuating market prices. The small and scattered resources meant the supply was always limited. It was hard work for the cutters who camped in the bush and lived off corned beef supplemented by fish caught in the many creeks and waterholes.

When World War II arrived, many men preferred to join the services or take other jobs, as being a tea tree cutter was not an easy life. Yet, the outbreak of war led to a surge in demand for tea tree oil.

The government commandeered all stocks of tea tree oil, and efforts were made to stockpile oil as the Army and Navy wanted to provide first aid kit supplies for men serving in the tropics.

Demand significantly exceeded supply, prompting the development of synthetic germicides to fulfil wartime requirements. During the war, the production of synthetic germicides and mass-produced penicillin soon swept in and fostered a strong belief in the miracle of modern manufactured drugs. Penicillin was effective and cheap, sending natural medicinal products to the margins.

After the war, large pharmaceutical companies produced numerous popular synthetic products, supported by polished and well-funded marketing. At the same time, less widely available natural remedies, such as tea tree oil, were overshadowed. This led to a gradual decline in the industry, and by the 1950s, only three stills were left functioning in and around the Bungawalbyn Creek area

The Swamp Strikes Back: Revival in the ’70s

Progressively, things changed with a general awakening to the harmful effects of synthetic products and an environmental enlightenment. As environmental awareness grew in the 1960s and 70s, interest in natural remedies reignited. Many plants were once again revealed as sources of effective medicines, and natural products, such as tea tree oil, saw a resurgence in popularity.

By the 1970s, the demand for tea tree oil had risen again to revitalise the industry. Bush stills and cutters reappeared on the scene, continuing the hand-cutting, trimming, and bagging methods of the early days, but with much better transport and no need to camp in the bush.

Chemists who continued Penfold’s work, such as Howard McKern, Dr Eric Lussak, Dr Owen Hellyar and Dr Ian Southwell, worked in the New South Wales Department of Agriculture and the Wollangbar Agricultural Institute after the museum’s section dealing with essential oils closed in 1979. They established field trials over many years.

The Forestry Commission of New South Wales established a feathery tea tree trial over two acres in Braemer State Forest, between Casino and Grafton, in 1949, under the tutelage of research forester David Dun. The Commission was keen to learn about the tea tree’s silvicultural requirements. Seed was selected from high-oil-yielding trees, and the trial was designed to examine the effects of tree spacing and harvesting frequency on oil production. A further 10 acres were planted at a spacing of six feet by six feet. Unfortunately, as the economic interest in tea tree oil waned soon afterwards, the trial was abandoned, and no results were measured.

Brian Small, who worked for G. R. Davis Pty Ltd, which had broad interests in the essential oils industry, learned about the trial in 1965 when the trees were 16 years old. He obtained approval to continue the experiment between 1966 and 70, and demonstrated the feasibility of mechanically harvesting tea trees with a forage harvester and cart, the first demonstration of its kind. Information he gleaned from this trial was used to design subsequent plantation experiments at Castle Hill, Duck Creek near Ballina and Whiporie State Forest. His work laid the foundation for the development of tea tree plantations from the 1970s.

A Family Dream Grows in the Swamp

Enter Eric White, who migrated to Australia from Kenya in 1961. He worked as a cameraman for ABC in Sydney. However, after discussing the medicinal properties of feathery tea trees with his neighbour, Brian Small, he became a tea tree evangelist. He eventually decided to leave his job and head to the north coast of New South Wales, working closely with Small in the epicentre of feathery tea tree country—the Bungawalbyn Creek area, where he lived in a shed on-site, learning as much as possible.

A family medical incident convinced him of the medicinal value of tea tree oil. His stepson, Christopher Dean, had been travelling in Africa and contracted a fungus infection under his toenails. He tried various medicines, seeking advice from doctors and pharmacists. At the end of his odyssey, he landed in London, and a specialist declared the infection incurable and advised having his toenails removed. Luckily, Dean met up with his brother, who carried some Australian tea tree oil. His intense itching and pain lessened almost immediately after applying the oil; eventually, his feet recovered, and the oil cleared up his fungal infection.

White scoured the swamps of Bungawalbyn for the best oil-yielding trees, searching for the remaining stands of feathery tea trees still standing after so many years of exploitation despite being regarded as pest trees by the sugar cane and dairy farmers.

He was seeking genetic stock for cultivation and wanted to find the purest genetic traits of tea trees to establish a high-quality plantation. Part of his problem was a significant variation in the quality of oil produced from the natural trees. One tree could produce oil of high grade therapeutically, while a tree alongside could produce oil high in cineole, a low-grade antiseptic and useless for the uses the tea tree was famous for, as it is a skin irritant. Also, oil from some trees may be deficient in desirable terpinene-4-ol and thus have only a marginal effect.

The Australian standard for producing and selling tea tree oil stipulates that cineole must be at levels no greater than 15 per cent and terpinene-4-ol must be at levels of at least 30 per cent of the oil.

White discovered a grove of mother trees with exceptional genetics, which he believed was the best source of tea trees in the world. It was in a flood-prone area that could carry up to 5.5 metres of flood waters across the wetland. He was determined to revive the Australian tea tree industry on a much larger scale, utilising tea tree plantations. He applied to the Lands Department for a lease to cultivate the first plantation after conducting soil tests and raising seedlings.

In 1976, he was granted his lease on a Thursday, marking the birth of the first thriving tea tree plantation, Thursday Plantation. Meanwhile, Dean returned to Australia penniless but was determined to work with his stepfather, even though the first three successive plantings had been destroyed by flood and drought. To make matters worse, White suffered a heart attack in 1978, and his declining health and lost savings meant his dream was all but gone.

Dean’s firsthand experience convinced him of the product’s power, and he took over from his stepfather. In 1979, he left city life to move to Bungawalbyn with his wife and young son, continuing to cultivate the plantation. He lived in an old tractor shed—no electricity, plumbing, or telephone and more than 17 kilometres from the nearest town.

The plantation era

Dean was eager to succeed in his new and risky venture. After meticulous planning, he continued collecting seeds and successfully established the plantation. It didn’t take long for the first batch to be distilled, but finding a market proved challenging. The essential oil buyers rejected his product, so he could only sell it at the same price as second-grade eucalyptus oil.

Undeterred, Dean was determined to make Australians recognise the actual medicinal value of tea tree oil and aimed to ensure that every household in Australia had a bottle of it. He studied business management at the local university, where he learned about the importance of marketing.

Starting small, he distilled enough oil for the local markets, bottling under kerosene lamps with hand-drawn labels. His marketing strategy was to use handwritten signs to highlight the product’s natural features and the results of earlier research.

People observed remarkable healing results after using the oil. Rashes, sores–you name it–all began to disappear for those with chronic skin problems. Gradually, their reputation grew, and as demand increased, they started selling in health food stores.

By 1987, Dean had formed a family company and expanded into a 60-hectare former cane farm near Ballina, planting over a million trees and opening a tourist centre, which helped make tea tree oil a household staple. He also founded the Australian Tea Tree Industry Association, encouraging others to join the revival. He still obtained about a third of his supplies from the natural swamp country.

Dean was a pioneer. By the decade’s end, farmers realised the economic advantage of rehabilitating the drained swamps with a natural crop instead of fighting against the land, which did not take kindly to clearing and chemical use. Other plantations were established across the swampy landscape between Port Macquarie and southern Queensland, with the majority centred around the Richmond and Clarence Valleys.

In theory, harvesting from plantations should help increase the production of tea tree oil, particularly if the right land is chosen and developed, allowing for easier access to more “leaf” and if seed is selected from trees known for their high quality. But in practice, that hasn’t been the case. The major impediment has been the high cost of establishing plantations.

However, using modern, high-capital machinery and advanced technology has gradually lowered unit costs compared to bush harvesting, where the dense bush in natural stands foiled all attempts at mechanised harvesting. Many plantation growers maintain their nurseries, where seedlings are cultivated in polystyrene cell trays instead of open rootstock to minimise transplant shock. Planting layouts may achieve a density of up to 30,000 to 40,000 seedlings per hectare.

Trees are usually harvested 12-24 months after planting and then on a 12-18 month cycle, when they are about one to two metres tall. They are cut around 15-50 centimetres above the ground. Oil concentration is usually higher between November and March.

For the growers in the market now, plantations are necessary as natural stands will struggle to meet the world’s demand.

But the story hasn’t been without setbacks. A massive planting boom in the 1990s led to an oversupply crisis, resulting in lower prices and stalled growth. Yet the resilient industry bounced back, bolstered by ongoing research, niche markets, and tea tree oil’s growing reputation as a natural alternative to synthetic drugs and cosmetics.

From Bungawalbyn to the world

From the muddy floodplains of Bungawalbyn Creek to pharmacy shelves worldwide, the journey of tea tree oil is a classic tale of Australian grit, innovation, and bush knowledge.

In the remote swamps of northern New South Wales, it’s here that a small, unassuming tree changed the face of natural medicine.

Another fantastic tale about a staple in many Australian bathroom cabinets. A great read.

Thanks Rob.

It brought back memories of my time up in the Ballina, Richmond and Clarence River regions.

As always, a great read.

A most informative read Robert.

Thanks to my buddy Frank, a forester in WA, who sent me this article as it mentions my father, Dr Southwell. A great summary of the industry- I’ll send it to Dad – he’ll be very interested. A funny memory is Dad bringing home ginger and tea tree toothpaste for us kids to use. It was awful!!

Great to hear from you, Tim. That anecdote about the tootpaste is gold, thanks for sharing.

I hope your dad approves of the story!

This is a great story about the industry that I was involved in many years ago. I worked with my brother-in-law James Stewart, better known as “Snowy”, who lived at Bungawalbyn in the early 80s.

My memories stand tall of meeting Christopher Dean, who was a polite young gentleman who lived in a little shack on Moonem New Italy Rd.

We arranged to deliver our bags of tea tree to the pot for distilling several times a week, and Snowy would cook the pot as we say.

Your story brought back lots of great memories, thank you very much.

Great to hear from you, Glenn. Thanks for sharing your memories of working in the industry many years ago.

As said previously by your followers Robert, another great story brought to light about Australia, thanks.