Conservation in Australia is largely a matter of pious intentions.

Germaine Greer

When Anthony Albanese’s Labor government came to power in May 2022, environmental groups quickly pressed their wishlist onto the incoming ministers. Near the top was a global conservation commitment to protect 30 per cent of Australia’s land and oceans by 2030, part of a United Nations-endorsed pledge to halt biodiversity decline.

While not a prominent feature of the Labor election campaign, the policy gradually gained traction soon after the political dust settled. In December of that year, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek signed Australia up to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, along with nearly 200 other countries, formalising the 30 by 30 target and committing Australia to one of the largest land acquisitions in its history.

It all sounds noble. However, since then, the story has taken a familiar turn with grand announcements, extravagant spending, media hype, but very little practical follow through.

Achieving the 30 by 30 goal requires converting tens of millions of hectares of land into reserves or protected areas. However, instead of actively managing these landscapes, the government has fallen into the trap of preservation through acquisition. Productive outback stations are being purchased and transformed into national parks or Indigenous Protected Areas, often with little consideration for who will maintain them, how they will be funded, or what is actually being achieved for biodiversity. Equally, because the current preservationist model wants to exclude human use of the land, traditional owners may have to surrender rights to access and use of the land.

While the headline commitment sounds virtuous—protect nature, save species, and combat climate change by expanding national parks and other preservation areas—ordinary Australians haven’t had the chance to pause and ask what it would cost, and whether the policy would deliver real benefits.

There is one thing I know for certain. The costs are substantial, both financial and social. Yet, the public hears little about the long-term funding gaps, the weed and feral animal invasions, or the economic damage inflicted on local communities. In practice, almost nothing is said about what “30 per cent protected” means. What are we protecting if these lands are left unmanaged, degraded, and inaccessible?

As a professional land manager, I see only a policy that merely appeases activist groups that are seldom satisfied for long. The only available land that could assist the government in meeting its target is remote food-producing properties, eliminating all human use from the area.

Who pays?

The Albanese government has since released a National Roadmap to guide Australia toward the 30 per cent target, but it reads more like a wish list than a plan based on practical land management. As with anything related to this government, the costs remain unclear. A $250 million funding package under the “Saving Australia’s Bushland” program was announced in 2023. Yet, preservation lobby groups like the Australian Land Conservation Alliance (ALCA) have been calling for at least $5 billion over the next five years.

This is only the beginning. Environmental NGOs have hailed the 30 by 30 policy as the minimum requirement. However, their demands continue unabated. Each new reserve triggers calls for further acquisitions, increased funding, and more regulations. Private landowners are viewed with suspicion, and traditional land uses such as grazing or sustainable forestry are portrayed as threats, despite preserving ecological values for decades.

This disparity highlights the tension between government commitments and the expectations of environmental organisations. Meanwhile, none of these groups are held accountable for the results, such as poor management, loss of species, and the unchecked spread of weeds and feral animals.

The scale of what’s required is staggering. Australia currently has around 22 per cent of its land within preservation tenure. To reach 30 per cent, over 60 million additional hectares need to be added to the reserve system, an area nearly the size of New South Wales. That means purchasing vast outback cattle stations and designating them as national parks, carbon farms, or Indigenous Protected Areas.

Yet as governments rush to acquire land, questions persist about who will manage it and how. Many newly established reserves are situated in remote areas where traditional land managers like pastoralists have been displaced, and preservation management often amounts to little more than benign neglect. Rangers are few, funding is limited, and weed and feral animal infestations are allowed to run rampant. The romantic idea of “saving the country” seldom aligns with boots on the ground.

The idea that locking up land away from traditional European land practices will save native plants and animals is a fantasy. Numerous examples of failures exist. Species that once thrived in managed landscapes now struggle when fire regimes change, weeds proliferate, and no one remains to undertake the difficult task of caring for the land.

Communities affected are witnessing their local areas stifled by diminished economic development. Former agricultural strongholds are becoming wastelands dependent on government funding, whether they are national parks, carbon farms reliant on carbon credits, or passive Aboriginal land.

Queensland’s buying spree

Before signing the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework in 2022, Queensland’s Labor government announced plans to raise the state’s protected areas target to 17 per cent by 2030, with a substantial $262.5 million allocated in funding. More than 15 million hectares, or 8.59 per cent of Queensland, are already protected under the Nature Conservation Act 1992—an area twice the size of Tasmania. Achieving 17 per cent by 2030 would require doubling that area in less than six years. They now aim to match the federal pledge of 30 per cent, resulting in a protected area system the size of Spain!

The Queensland government acquired Springvale Station near Cooktown in 2016 for $7 million. The 56,000-hectare property was accused of contributing sediment runoff to the Great Barrier Reef, which prompted the purchase for “environmental rehabilitation.” However, the Chief Scientist for Queensland, Dr Geoff Garrett, stated at a public meeting in nearby Lakeland before the purchase that there was no “measurable sediment runoff from the Upper Normanby catchment” into the reef.

It wasn’t until around 4,000 head of cattle were removed from the local economy, the station was split into a national park, and the rest allocated to a local Indigenous group, that the Great Barrier Reef faced increased threats.

The Environment Department claimed that the design of the massive irrigation dam was unknown and deemed unsafe, particularly since construction hadn’t been completed. However, the hydrologist who designed the dam and local engineers argue otherwise. This is supported by the dam wall’s capacity to withstand heavy rainfall, including 300 millimetres in one night when Cyclone Etta struck the area in 2014, along with an effective spillway and fishway that were implemented.

The effectiveness of the erosion control measures has been scrutinised, with many experts questioning the intervention’s long-term impacts. The demolition of a 1,200-megalitre dam was meant to reduce sediment flow, but it sparked a furore over the balance between environmental goals and agricultural needs.

One engineer predicted that the 30,000 tonnes of soil from the demolished dam’s earth wall would eventually wash into the river system and settle on the Great Barrier Reef. Neighbours observed long silt plumes in the East Normanby River after water was siphoned from the dam into the river.

After a severe bushfire in the new reserve in January 2018 affected neighbouring landholders, they threatened to take the government to court for failing to contain or prepare for the bushfires that raged through the region for weeks. It quickly became apparent that the parks agency had no management plan for the new park or a decisive strategy to fight fires. Instead, they let the whole park burn out because they refused to conduct any backburns.

The same could be said for the nearby Kings Plain Station, where approximately 70,000 hectares were also burnt. The property is now owned by the Endeavour Trust and is managed like a national park as a preservation reserve, following de-stocking for benign carbon farming, which has exacerbated the damage suffered by pastoralists. The Endeavour Trust blamed the fires on arsonists but had no effective strategies to control fires when they occurred. All they could say about the damage was:

The fires cost us $150,000 in lost carbon credits alone.

That was peanuts compared to the losses incurred from damaged fencing, loss of feed and disruption to grazing areas experienced by their neighbours.

The government purchased Bramwell and Richardson Stations in August 2021 and publicly announced the acquisition the following February. These two stations in far north Queensland cover a combined area of 131,900 hectares. Once the site of thriving grazing and eco-tourism operations, they are now designated for return to the traditional owners under the Cape York Peninsula Tenure Resolution Program and are set to be declared national parks. The price was $11.5 million.

Premier Anastacia Palaszczuk was effusive after the Bramwell and Richardson purchases, telling the media:

This is one of the most significant purchases in Queensland history – linking close to one million hectares of protected land in a picturesque part of our state.

The remaining local graziers don’t share that optimism. They are worried about the lack of funding for these reserves once established, despite the government’s announcement that their purchases represent a win for the local economy. However, concerns persist about the future of the Bramwell Junction Roadhouse and Tourist Park, a vital component of the local economy.

Then came the purchase of The Lakes Station in early 2022, a 35,300-hectare property in the north of the state, which was also purchased for conversion into a national park. In recent decades, more than 20 former stations and over one million hectares, including Kalinga, Crosbie, Strathmay, Killarney, Dixie, and Wulpan Stations, have been acquired across Cape York.

In 2006, the federal government acquired the 135,000-hectare Bertiehaugh Station near Weipa, now called the Steve Irwin Wildlife Reserve, after Terri Irwin insisted that the land be named in Steve’s honour and that they be given the chance for hands-on management.

After the state government unexpectedly imposed 500-metre buffer zones around the reserve’s waterways, Cape Alumina’s planned bauxite project was halted without prior warning to the mining company.

The Irwins have fought to close the public road, further limiting tourism in the area. However, with backing from the Western Cape Chamber of Commerce, the Cook Shire Council is determined to keep the road open, highlighting its importance for tourism and economic development in the region. They refuse to be intimidated by lawyers. Traditional owners have also expressed concerns about access to the reserve for cultural reasons.

Local grazier Emma Jackson is worried about the future of the cattle grazing industry on Cape York:

There’s this perception that when you’re working the land in cattle or horticulture, you’re not working with the land, that you’re not doing the right thing, and that’s simply not correct.

Then, following the 30 by 30 announcement, additional purchases were made: the 352,500-hectare Vergemont Station near Longreach for $21 million, the 203,000-hectare Tonkoro, and the neighbouring Melrose Stations near Winton. These acquisitions were backed by a substantial private donation facilitated by a US-based environmental organisation, the Nature Conservancy.

However, the move wasn’t welcomed by the local community. Local MP Stephen Andrew described the environment minister as embarking on.

a furious shopping spree, snapping up some of the most productive, privately-owned grazing lands in Queensland.

Many millions of hectares of Cape York Peninsula with ocean frontage from Karumba to Cooktown are now in the hands of managers for some form of preservation management, be it national park, Aboriginal land or carbon farming, all of which have no resources to prevent or protect Australian interests. The same applies west of the Queensland-Northern Territory border to Darwin.

There is the risk of disease entry, and if or when Foot and Mouth Disease, Lumpy Skin Disease or insects or animals enter Cape York, they will not stop as the intrusion will go unnoticed and unchallenged for some time. In Queensland, there are virtually no Department of Primary Industries field staff in these regions to identify and contain any problems.

A North Queensland rural real estate agent told me:

In practical reality, taxpayer funding exists to acquire land, but zero intention to manage these vast, remote areas. I believe the public will think that all national parks will be like the one near them – camping areas, park benches, walking tracks, ranger staff to manage and educate, etc.

But the reality is that their presence is not welcome. The government has no intention of resourcing these areas for proper management.

It’s a politically motivated, short-term, vote-grabbing exercise usually concentrated in the lead-up to every election.

New South Wales follows suit

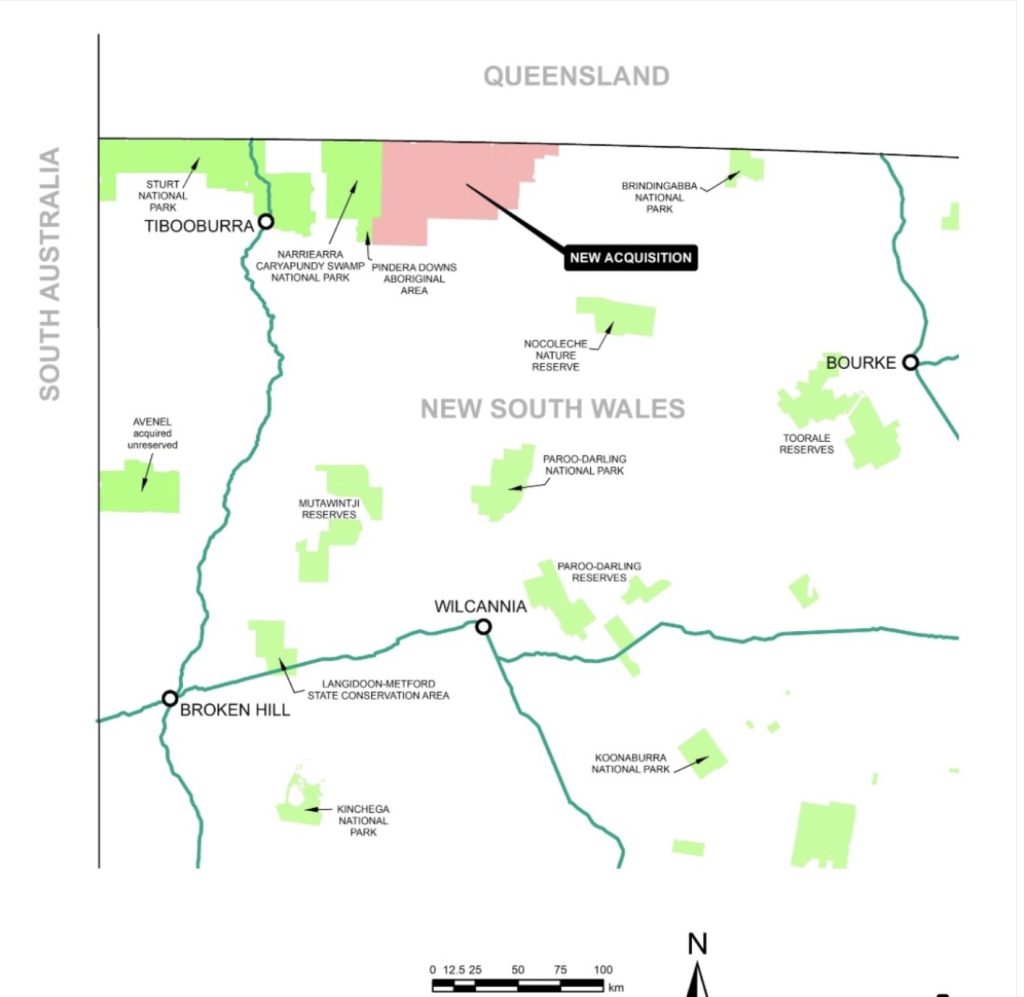

New South Wales has not lagged far behind Queensland in this mad rush to buy outback stations and convert them into national parks. Since 2019, the New South Wales Government has spent over $180 million acquiring more than 600,000 hectares of land, much of it previously productive pastoral country in the Western Division. Ministers often laud these acquisitions as “historic,” “game-changing,” and “generational”. But they have also triggered concern, resentment, and deep cynicism among landholders and local communities who feel blindsided by a green agenda masquerading as good governance.

The most significant single purchase was Thurloo Downs, a sprawling 437,000-hectare property near Tibooburra in far north-west New South Wales. Touted as “the largest national park acquisition in the state’s history,” Thurloo was acquired in early 2023. However, the glossy conservation headlines concealed the reality that a productive grazing enterprise was shut down, along with the economic activity and jobs it supported. Once again, promises of tourism jobs and “nature-based employment” filled the press releases, but local experience suggests that once the cattle are gone and the headlines fade, so too does the investment.

Concerns have also arisen regarding the adequacy of resources allocated for managing such an extensive area. The Public Service Association highlighted that only five staff members were designated to manage the property, raising questions about the feasibility of effective preservation efforts across such a vast and remote landscape.

Local graziers pointed out that feral goats, pigs and foxes would now run rampant. The fire risk would increase as fuel loads built up. Productive grazing land was being locked away with no plan for its management.

Even before that, the state had acquired properties such as Narriearra Station, Koonaburra, and Avenel, adding hundreds of thousands of hectares to the reserve system. In many instances, landholders were not engaged in good faith discussions and found themselves competing with the state government, which was an inflated buyer in a tight rural land market. While the environmental lobby praised the speed of park creation, locals pointed out that fences, firebreaks and feral animal control programs quickly fell into disrepair once the government took charge.

In July 2023, the state government added Comeroo, Muttawary and Maranoa stations, remote and rugged 93,000-hectare cattle properties near Bourke, to its growing list of acquisitions. They too are set to become a national park, with plans to hand management over to the National Parks and Wildlife Service in partnership with Indigenous groups.

Once again, while the preservation objectives are commendable, critics—including the Pastoralists’ Association of West Darling—warned that Comeroo’s isolation, scale, and complex water systems made it a highly questionable conservation target. The property has little to no infrastructure for tourism and was purchased without any clear plan for staffing, fire management, or feral control. The concern is that it will become yet another “lock-it-up-and-leave-it” park, where cattle are culled instead of mustered, feral animals thrive, and fires go unchecked.

One prominent case that exemplifies this neglect is Yanga Station, which has become a case study in what occurs when governments overlook management. The pioneering purchase of a 71,000-hectare former merino sheep empire near Balranald happened in 2005. In its heyday, Yanga was a showpiece property with functional water infrastructure, carefully managed wetlands, and a thriving local workforce.

Since Yanga National Park was established, locals claim that the previously healthy red gum wetlands have deteriorated, pest animals have multiplied, and biodiversity outcomes have regressed. Infrastructure has fallen into disrepair, water control structures have been neglected, and fire has become a constant threat due to overgrown fuel loads and an unwillingness to carry out early-season burns.

Locals were so concerned that they formed an advocacy group calling for the return of Yanga to local management. Their simple message was if the government can’t manage it properly, give it back to those who can.

Another failed purchase was the federal and state governments’ purchase of the historic Toorale Station near Bourke in 2008, a move intended to benefit the Murray-Darling River system. Three years after the 91,000-hectare property was bought with the promise of returning irrigated water to the river, some of the dams and irrigation channels are still in place, despite their removal being a central plank of delivering environmental flows.

A 2009 decommissioning plan identified significant environmental barriers to removing the infrastructure, noting that a new ecosystem had developed over the station’s 150-year history. The full cost of dismantling the dams and channels was estimated at $79 million. Seeing neither the promised ecological restoration nor economic compensation, locals were angered over the wasteful and misguided intervention.

Another problem is that the New South Wales national parks estate has already expanded beyond what the Department of Planning and Environment appears capable of managing. Over the past decade, park infrastructure throughout the state has fallen into disrepair. Visitor facilities are deteriorating, traditional owners are frustrated with being excluded from decisions, and the skilled workforce required to manage these lands has been severely diminished due to funding freezes and budget cuts.

Worse still, the political obsession with land acquisition has created perverse incentives. Ministers can gain media attention by announcing new parks instead of properly resourcing the management of existing ones. While feral pigs, goats, and foxes devastate native wildlife across the outback, national parks offices are frequently staffed by part-time rangers who cover areas the size of small countries. There is little hope for ongoing efforts in fire mitigation, weed control, or threatened species recovery.

As in Queensland, New South Wales has succumbed to the romantic illusion that simply “locking up” land in national parks will protect it. In practice, this often shields the government from scrutiny. It enables politicians to pose as saviours of the environment while ignoring the land degradation, species loss, and local economic collapse that their policies are fostering. Add to that the government’s inability to cover the cost of essential services such as hospitals, education and policing, and it becomes clear that pouring hundreds of millions into under-managed preservation estates is not just poor environmental policy, it’s a profound misallocation of public funds driven by ideology, not evidence.

This is preservation through press releases, not through practical land stewardship. It looks impressive from a minister’s office in Sydney but means little to the graziers witnessing weeds creep through abandoned homesteads and pigs ravaging the wetlands that once supported flourishing birdlife.

Western Australia’s preservation mirage

In Western Australia, a similar story is unfolding. Pastoral leases are being returned under conservation and Indigenous tenure, with increasing pressure to achieve the 30 by 30 target. This comes despite a report released in 2021 regarding the status of Western Australian pastoral rangelands, which raised concerns about declining vegetation in certain regions. The report highlighted the need for better land management practices and more support for those responsible for overseeing these vast landscapes.

In 2024, the federal government announced new Indigenous Protected Areas across Western Australia, including on Nyamal, Wudjari, and Yindjibarndi country. These vast areas were said to “empower Traditional Owners” and contribute to biodiversity goals. However, similar to Queensland and New South Wales, management support has often failed to match the transfer of land rights.

Driving through the Kimberley and around Broome, it’s clear that some former stations now under Aboriginal or conservation control are in poor shape. Buildings are derelict, and fences have fallen. Invasive species like buffel grass and Parkinsonia are spreading unchecked. There are few visible signs of active land management.

Supporting Indigenous rangers is a worthy aim, but it must be backed by rigorous, science-based land management planning and delivery. Without this foundation, it risks becoming merely symbolic, akin to a land handover without meaningful stewardship.

Even well-funded programs encounter challenges. Managing remote areas is logistically difficult and costly. Ranger turnover is often high. Long-term investment is needed for fire control, weed spraying and feral animal reduction, rather than just good intentions and the occasional helicopter drop of baits.

Good intentions are not enough

What ties these examples together is a constant failure to match ambition with responsibility. The 30 by 30 target has turned into a feel-good slogan. However, a more intricate and disheartening reality lurks behind the media releases and aerial images of rugged landscapes.

Taxpayer funds are directed towards purchasing land, yet little is allocated for its management. Working pastoral properties that once supported families, provided jobs, and bolstered local economies are now being turned into parks that lack staff, fences, and a viable future.

Conservation isn’t achieved by merely locking up land and walking away. It requires stewardship with real, active, on-ground work. The kind of work that graziers, timber workers, Indigenous rangers, and experienced land managers used to do every day.

Even academics who have previously pushed preservation via benign neglect have recognised the problems. Former Queensland Chief Scientist Professor Hugh Possingham from the University of Queensland admits that no research proves national parks are the best way to protect an area. A grazier dealing with feral animals and weeds cares for the land better than government departments with limited resources:

There’s a whole bunch of people who love national parks, and who have confused the outcome with the action. They think the aim is now to create more national parks, not to protect biodiversity.

Former Australian of the Year, Tim Flannery, agrees, arguing that the biggest problem stems from the notion that simply proclaiming a reserve results in the protection of biodiversity:

Government agencies responsible for biodiversity protection have allowed their scientific capacity to erode to the point where it’s hard to be sure how many individuals of most endangered species survive.

He claims that attempts to save endangered species involve risks that bureaucracies are increasingly unwilling to take:

It often seems preferable to let a species die out quietly, seemingly a victim of natural change, than to institute a recovery program that carries a risk of failure.

Flannery particularly targets Kakadu National Park as an example of failed national park management:

Between 1995 and 2008, the abundance of small mammals found in the park declined by 75 per cent…some of the species recorded in 1995 can no longer be found there.

The public never voted on this massive, radical land use change policy, and there has been no public consultation or parliamentary debate. Stations like Bramwell had two long-term rolling pastoral leases. The government and its supporters fail to grasp that millions of taxpayer dollars have been spent securing Crown land—land they effectively already owned anyway.

The public lacks the opportunity to understand the real impacts of this radical policy. The track record is troubling. Many of the converted stations remain unmanaged or poorly managed. Traditional owners are often given responsibilities without the sustained funding, training, or infrastructure necessary to oversee vast and remote landscapes. Weed infestations go unchecked, while feral pigs, cattle, and cats proliferate. Fire regimes have collapsed. Some Aboriginal ranger groups are active and well-resourced, but others face impossible expectations with scant support.

And worst of all, research programs are generally short-term and ad hoc. There is no long-term, systematic monitoring of threatened species in national parks, unlike the actively managed state forests, where biological surveys are mandated.

The result is that large swathes of land, once grazed, burned, and actively managed, now slide into ecological decline beneath a green veneer.

If the federal and state governments want to be taken seriously about biodiversity, they must commit to what happens after the land is bought. The job doesn’t end with the acquisition; it begins there.

Otherwise, 30 by 30 will simply be another costly illusion, a billion-dollar exercise in appearing virtuous, while allowing the bush to deteriorate.

Robert what is the investment in dollar value per hectare spent by government on land management across the protected estate? This would be worthy to demonstrate the miniscule amount spent by government on stewardship.

It is a good question Jim. I don’t have figures for the whole country, but I do know that in New South Wales, the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) spends approximately $32 per hectare each year to manage its 7.8 million hectares of land. Unlike the Forestry Corporation, which generates $415 million in revenue each year from its 2 million-hectare estate, NPWS only takes from the taxpayers’ purse.

Based on 2023-4 reports, in Victoria, the figure ranges from $23 to $58 per hectare, and in Queensland, it is a paltry $16 per hectare.

Hi Jim, when I worked for the government in WA about 5 years ago we had 11c per hectare per year for pest, weed and disease management.

Thanks Robert for this review. Time is well past overdue for a review of current failed conservation policies and management as well as the 30 X 30 proposal, including regular low intensity fire, intense bushfires, ecosystem change, increased eucalypt decline, adaptive management, weed control, pests, neighbourly relations, costs to communities etc etc. Fire policies that allow large areas to remain unburnt, 50-year return fire intervals and large fuel loads across landscapes are crazy land management outcomes. The AWC approach to conservation is a better approach.

Robert, thanks for the excellent summary of this terra nullius driven environmental, social and economic tragedy.

For the past four decades, monetised activist NGOs have been the enablers of state and federal governments in making ever dumber conservation land related decisions. Dopey environment ministers and their bureaucracies have smashed primary industries and regional economies and communities with populist “environment” decisions. The triple bottom line negatives these activist driven environmental boneheads have delivered, would amount to uncounted billions of dollars in wasted taxpayer funds and economic losses.

Meanwhile, the national environmental scorecard sees an ever-growing list of threatened and critically endangered species. While activist NGOs continue to strip hundreds of millions of dollars of tax-deductible donations from mislead members of the public, the campaigning continues.

If the environment space was not dominated by boneheads, by now someone in authority would have asked the question: If we keep changing land tenure at great cost and always get a worse environmental outcome after the change, why are we so dumb that we do the same thing and always promise a better environmental outcome?

Recommendations have been made to Victorian inquiries for all Victorian Environmental Assessment Council predictions re better environmental and other outcomes be audited, before more land suffers the curse of lockup and neglect mismanagement.

Unfortunately, all boneheads share a common trait of never looking back.

Good article thanks Robert. In the 1990’s the Branch I was managing for CALM was given some $35 million to purchase pastoral lands in the Gascoyne/Murchison regions as part of a restructuring strategy. The money was once-off and came from Capital (ie borrowings).

However, the recurrent annual management costs were to come from the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF), where CALM had to compete with key items such as Health, Education, and other essential services. Guess who won out? Not land management. The purchases also came with houses and other infrastructure that was expensive to maintain, so it was allowed to degrade over time. Closures of waters reduced grazing pressure from native and introduced species, but this led to increased fuel loads and fire risks.

“Benign neglect” is a good description of the current management of these areas.

On a more positive note. Working as a consultant for a new iron ore operation , we were required by the EPA to propose suitable environmental offsets for damage that would be caused by the mine. The small mine footprint was surrounded by four former pastoral leases managed for conservation: by AWC, Bushheritage, an indigenous Protected Area and CALM. We agreed to have the mine set aside some 5c for each million tons of ore mined into a fund that would pay for management programs on the adjacent areas. The money was disbursed annually through a committee that represented the five parties. I appreciate that this approach is restricted to mine-life, but some mines can operate for decades.

OOOOPS Robert, it was 5c/ton of ore, not a million! The mine was scheduled to produce some 5MTPA or $250,000 pa for land management.

Robert, regarding the efforts to actually manage the conservation threats in WA see the attached https://audit.wa.gov.au/reports-and-publications/reports/conservation-of-threatened-ecological-communities/

Also note that the WA government has already given up on eradicating the Polyphageous Shot hole borer, one of the greatest real threats to biodiversity.

Thanks, Gavin. The report is revealing not just for what it says, but for what it leaves out.

Buried beneath layers of bureaucratic jargon is a glaring omission. There’s virtually no detail on the practical actions the department is actually taking to conserve threatened ecological communities. The emphasis seems overwhelmingly focused on identifying and listing threats, yet when it comes to addressing those threats, the silence is deafening.

This isn’t unique to WA. It mirrors a national pattern where lots of resources go into paperwork, classification, and reporting, but very little in the on-ground management or active recovery efforts.

Even more concerning is the lack of basic monitoring. Across Australia, vast areas are designated as “protected”, yet we’re not systematically tracking whether species or communities within them are recovering, declining, or simply holding their ground. So, how do we know if the current lock it up mentality of protection is working at all? And why is no one asking whether doing nothing (what I call “benign neglect”) is actually failing the very species we claim to be saving?

As I’ve highlighted before (see https://www.robertonfray.com/2023/05/02/proof-that-species-are-declining-in-our-reserves-set-up-to-protect-them/), there are clear examples where this passive approach has allowed conditions to deteriorate. This report confirms that too much of our conservation effort is happening on paper, rather than in the field with pragmatic, active management.

Gidday Robert. I couldn’t agree more that the “lock it up and leave it” approach to management of protected land won’t work, for all the reasons you have outlined. I do, though, draw your attention to two matters that I am familiar with:

Most of Cape York Peninsula has infertile soil and a long dry season so it was never productive, hence the lack of decent infrastructure. I have written a paper (unpublished) on that, having spent my agricultural science career in far north Queensland. That also meant that pastoral land management was decidedly casual, with local overgrazing common and uncontrolled fire ubiquitous.

The Darling River pastoral landscape has been an ecological disaster since at least 2006, when I first saw it, in drought, denuded by jumbucks, river banks unfenced. I have photos of bare land from then, now covered by inedible (except to numerous feral goats) shrubs, as has happened in great swathes of NSW, and starting to happen in Qld.

So pastoral lease management has not always been a friend to our land.

Thanks Joe. I am keen to read your unpublished paper if you are happy to share it with me. It sounds very interesting.