A false start: Captain Kent’s grand plans

Many might be surprised to learn that Fraser Island, famous for its pristine beaches and towering sand dunes, was once suggested as the location for a shark factory. Not just once, but on two occasions.

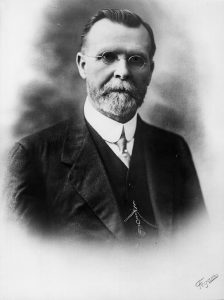

The first proposal came from an unexpected entrepreneur. Captain Herbert C. Kent of the Royal Naval Brigade was a former superintendent of the Bogimbah Aboriginal Mission, and a man with lofty ambitions and dubious credibility. Kent envisioned transforming the isolated estuary at Wathumba into a lively centre of industry.

In July 1907, he applied for government land grants on Fraser Island, seeking two large timber leases covering over 9,000 hectares. However, his plans extended well beyond logging. He intended to establish a fish cannery, extract oil from dugongs and “porpoises,” cultivate pearl oysters imported from the Torres Strait, and even grow sisal hemp.

One timber block stretched from Ungowa to Yankee Jack Creek, spanning the width of the island, alongside a 100-acre block at the mouth of Woongoolbver Creek for a wharf and township. The other timber block extended north from Sandy Point (near Moon Point) on the west coast to Indian Head on the east coast, plus an additional 100 acres at the mouth of Bowaraddy Creek. He also sought two blocks of 100 acres each to establish a sawmill, wharf, and fish canning factory.

The Maryborough Chronicle was effusive in promoting Kent’s plans:

With thousands of tons of fish and oysters, not to mention dugong, turtles, shrimp and crabs at our own very door, success to anyone well equipped to exploit same, seems a certainty.

Kent’s most audacious proposal was to move Aboriginal people to the island as a workforce, asserting they had a right to make a living there.

Kent intended to:

Gather all the district Aborigines and place them on Fraser Island, where they will be engaged in developing the resources of land and water.

Kent emphasised that his ambitions were more commercial than missionary. He noted that Professor Sydney Jackson, along with several directors from his syndicate, would soon visit the island and had patented a method for cultivating both pearl and table oysters, which they intended to farm in the Great Sandy Strait.

Political tensions and a web of deceit

Kent’s ambitions quickly encountered resistance. The Director of Forests, Phillip Mac Mahon, refused to grant him timber rights without a competitive auction, infuriating Kent, who had anticipated a concession. The sawmilling giants Wilson Hart and Hyne & Son also opposed his plans, fearing competition. They lobbied their local MP, William Mitchell, who expressed concerns in Parliament that Kent’s proposal equated to forced labour, if not outright enslavement of Aboriginal workers.

Undeterred, Kent aimed to gain public support for his proposal, informing the local newspaper:

Who can deny the right of the Fraser Is. blacks to earn their own living on their own island? ”Great Sandy Is. has been lying idle since it was created, excepting two companies (Wilson Hart Hyne & Son), who have invested enormous sums to work a portion of it for timber, and now, when an offer is made to develop it, all kinds of stumbling blocks are put in the way.

Kent persisted, asserting he had backing from “one of the largest companies ever formed in Australia.” However, the government became sceptical and demanded evidence of financial support. The situation took a dramatic turn when Brisbane businessman George Brown accused Kent of trying to sell timber concessions that he did not own.

Kent argued that after meeting with Mac Mahon and the Under Secretary of the Department, he sensed an undercurrent of objection to financing from a New South Wales syndicate. Therefore, he sought support from several Brisbane timber merchants to bolster the appeal of his proposal to the government.

In a stunning twist, Minister for Lands Joshua Thomas Bell revealed damning evidence in Parliament: Kent had fabricated his syndicate and had previously served multiple jail sentences for fraud.

Despite this scandal, Kent still managed to secure a small freehold parcel of land at Wathumba for a cannery. However, his shark factory never materialised. Equipment was delivered, an overseer was hired, but nothing ever came of it. Kent, much like his grand vision, vanished from the scene.

The real shark factory: a 1930s experiment

Nearly three decades later, Wathumba’s potential as a shark-processing site was revived. In September 1935, just months after the Maheno wrecked on Fraser Island’s eastern shore, three Brisbane businessmen, Benjamin Culpan and Messrs Hislop and Lambert, set sail on the Juanita to evaluate Wathumba’s suitability for marine harvesting.

They were thrilled with what they found. The waters thrived with sharks—up to 29 species, including eight types of “man-eaters.” They even spotted whales playing in Platypus Bay, a reminder of the unexploited marine riches that awaited exploitation.

The notion of catching sharks and extracting oil from them wasn’t controversial back then. Sharks were plentiful, just like they are today, and they didn’t have any allies.

It was common knowledge that sharks inhabited the estuaries on the island’s west coast. Hans Bellert maintained the telegraph line from Bogimbah to the Sandy Cape lighthouse on horseback. He also used to deliver mail to the lighthouse via the western beach. When they reached Coongul Creek, they waited until low tide to cross, as they didn’t want to swim the horses across, as the creek was a shark nursery.

By the following year, the trio of businessmen had formed Marine Products Pty Ltd and secured land at Wathumba, including the 160-acre block once granted to Captain Kent. Their vision was clear. It was to turn sharks into a profitable commodity, producing hides, oil, meal, and fertilisers for export.

A booming industry—for a moment

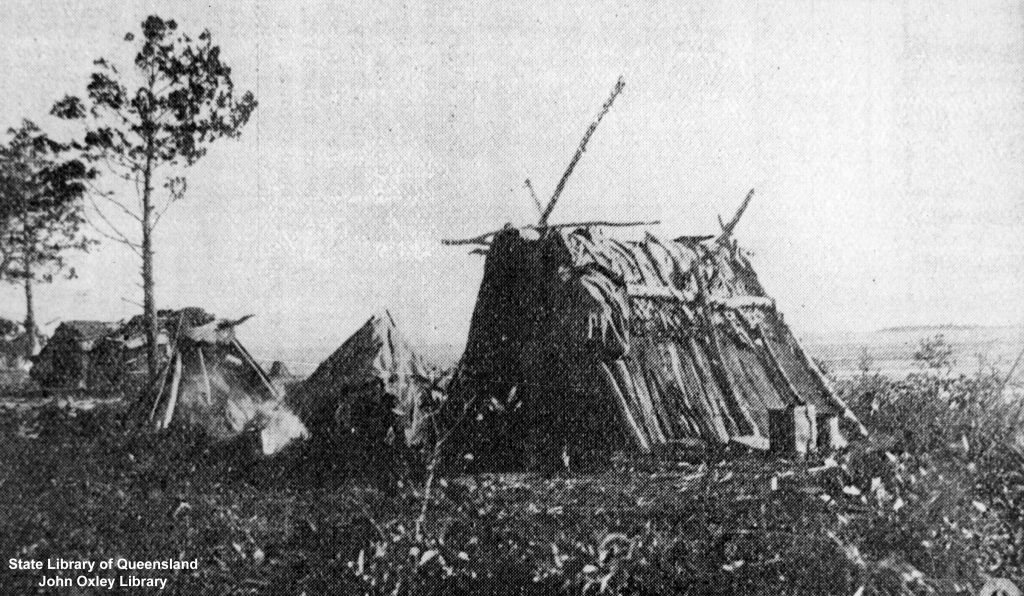

Timber, machinery, and refrigeration units arrived from Brisbane on the motor launch Dawn. Workers built a fish meal factory, men’s quarters, storerooms, a blacksmith’s shop, and a 50-foot jetty. A road was carved across the island to ensure year-round fishing, providing access to the back beach when northern winds made Platypus Bay too rough.

The company was quite confident about securing a sufficient supply of sharks, and renowned Maryborough fisherman, Dr. J. H. Bendeich, affirmed this when he spoke to Brisbane’s Sunday Mail:

“Many large whales pass the island on their way north to the warmer waters of the tropics. Should one of them be driven into the narrow strait by the killer-whales it invariably becomes stranded on the treacherous sandbars. Then the tiger-sharks, hammerheads, and other wolves of the sea gather in countless hundreds and in the turmoil and the tumult of the threshing waters soon rip the body of the leviathan to pieces”.

Shark hides became especially valuable after American scientists developed a tanning method that matched cow leather in durability while being considerably cheaper. The distinctive texture of sharkskin—known as shagreen—was sought after for polishing metals and even found its place in high-end jewellery manufacturing.

Investigations have revealed that shark skin consists of two layers. The outer layer, the epidermis, is called shagreen and is exceptionally durable. The jewellery trade recognised shagreen as a natural emery paper for polishing and grinding metals. With chemical treatment, shagreen can be removed from the hide intact, preserving the highly sought-after markings.

But the real money lay in by-products. Shark fins were sold to the Chinese market for soup, while blood was collected to produce waterproof glues, especially for aeroplane wings. Liver oil was rendered down for medicinal purposes and claimed to enhance eyesight, boost immunity, and prevent respiratory issues. Shark membranes found their way into violin strings and tennis racquets, while swim bladders were processed into isinglass to clarify beer and wine.

Shark liver oil had many medicinal uses. It was believed to promote wound healing, stimulate growth, increase resistance to infection, aid in combating fever and colds, improve eyesight, and prevent excessive skin dryness. It was also used as an overall general remedy for conditions of the respiratory tract and digestive system. Generally, livers were chopped into fist-sized chunks, rendered down in big vats, and the oil skimmed off, cooled, and canned, ready for shipment.

Shark meal involved specialised equipment such as hammer mills, drying machines, and conveyors. As the cooker, steam boiler, hammer mill, flaker dehydrator, and sacker completed their work, an aroma filled the air. The meal was popular pet food for dogs, cats, and poultry.

Dinghies set drum lines in Platypus Bay, reeling in sharks by the dozens. The company even considered catching dolphins, believing their jaw oil was the ultimate high-end lubricant for precision watchmaking.

For a short time, the factory buzzed with activity. Steam rose from the cooking vats, the hammer mill and dehydrator hummed, and an unmistakable aroma wafted through the air. The product? Fish meal, a highly sought-after pet food for dogs, cats, and poultry.

The sudden collapse

Then, just as swiftly as it had started, the venture collapsed. Whether the sharks were not as abundant as anticipated or the profits fell short of expectations remains uncertain.

By November 1938, Marine Products Pty Ltd was caught up in legal battles over its vessel, the Dawn, which had been seized because of outstanding debts. The factory stopped operations, leaving behind vacant buildings and unpaid workers.

One such worker, William Brennan, was left to maintain the abandoned site. The promised food supplies never arrived, and after three weeks of hunger, he was forced to walk 43 kilometres south to Bogimbah in search of a boat to Maryborough, only to find that his employer had vanished without a trace.

Ghosts of Wathumba

Today, the remains of Wathumba’s shark factory remain hidden in obscurity. There is not much evidence of any of the buildings. Over the years, the site was plundered by visitors keen on accessing equipment and building materials. Under the floorboards of the houses, fishermen found fishing gear and other items. Hans Bellert took the company’s solid-wheeled Palmer truck. It was too big for his launch, so he cut the chassis in half.

A rusting boiler, too heavy to move, is the only visible reminder of the factory. It sits in a small, overgrown area enclosed by wooden fencing just outside the camping zone and above the beach.

The neglected foundations indicate the site where ambitious entrepreneurs attempted twice—and failed—to transform Fraser Island into a hub for the marine industry.

For better or worse, the sharks persist, ruling the waters of Platypus Bay as they have done for millennia.

A very good read. The rapid turnover of best-laid plans.

A very interesting read. Amazing what was allowed in days gone by. Thankyou Robert.